Jíbaro

| Jíbaro | |

|---|---|

Monumento al Jíbaro Puertorriqueño dedicated to the Jíbaro, in Salinas, Puerto Rico | |

| Nationality | Puerto Rican |

| Occupation | Agricultural land tenants, sharecroppers, fieldworkers |

Jíbaro is the word used in Puerto Rico to refer to the country people, the people who farm the land in a traditional way.

Origin of the word

The first linguistic and etymological study made on jíbaro words was done by Óscar Lamourt Valentín. He analyzed many words used by jíbaros, as well as many words already known to be native or Taíno. After doing his multidisciplinary studies, he compiled the first etymological dictionary of the jíbaro language. He discovered the relationship with the Yucatecan Maya language. The word jíbaro is derived from the term caníbaro or canxíbalo, also xíbalo, since the x and j was used for the same phonem. But as a derived form, from the native language of the people of the Caribbean, Carib or Caniba, this word had suffered transliteration as well as several misinterpretations. As used in Puerto Rico or Borikén, it refers to "La gente de la montaña" or "mountain people", being Jíbaro or uajiro is to be natives or descendants from the jiba of the main caracoel, one of the "¡¡hermanitos gemelos" ("twin brothers"), recalled in the native mythology, the one called Temiban caracoel, also transcribed from the chronicle as Deminan. As related in the native oral story, on Temiban caracoel's back grew a jiba. Then, one of his brothers hit his back with a thunder axe. Then, from the jiba out came the turtle woman, CaUahNa (Caguana, in Spanish), whose symbol can be found carved in the Ceremonial Center of Caguana in Utuado, a native sacred area. So, as for the native people of Borikén or other islands of the Caribbean, jíbaro, or uajiro is the same, which is xíbalo, and it means "to be descendants from the male of the jiba", which is the mountain or dzemí (cemí), from where the native people came. All these native terms can be defined by Yucatecan Maya, as was explained in the linguistic and etymological studies of Óscar Lamourt Valentín, Huana N. Martínez and Uahtibili Báez, native descendants of Borikén. They analyzed more than 500 words, common "tahino" words and others that are attributed to Spanish or African origin, as bakiné, yanhotau. Lamourt Valentín was the first linguist and anthropologist to analyze the word jíbaro and other words from the jíbaro language, taking into consideration the historical and anthropological context. The native of Borikén is the jíbaro. The word taíno or tayno as it was obtained from the chronicle refers to a condition or an expression, not to the ethnic name for the native group. It must be noted that this term was used by archaeologists as a word for classification purposes. As such, it must be clarified that the word tayno does not refer to the ethnic group that inhabited the island, but the word jíbaro is the right word to use to refer to the natives of Borikén.

Historical Displacement of the Jibaro

When Operation Bootstrap took effect in Puerto Rico, the white Spaniards and white industrialists from the United States became ingrained with the elite society of the island. This resulted in a country-wide shift from an agrarian society to cosmopolitan society. Industry began to incorporate cheap labor, which led to the displacement of thousands of Jibaros from the mountain towns. This resulted from increased economic efficiency due to industrialization. Many of them would move to the coastal urban towns, which would result in major crowding.[1]

Sociological Ramifications of Displacement

The displacement of these Jibaros caused competition for low paying jobs, which was often relegated to non-white natives of the island. When the racial politics of these living conditions became apparent, many of the Jibaros differentiated themselves from those who were more noticeably black. They professed to be white rather than accepting the mixed-race background they were associated with.[1]

Historical Perception of the Jíbaro

There were many factors that influenced the perception of the Jíbaro, including literary depictions. One such literary depiction was El Gíbaro, a classic work written by Manuel A. Alonso, an author who sought to idealize the Jíbaro through a biased racial perspective. The other major factor was the Popular Democratic Party of Puerto Rico, which sought to idealize the Jíbaro for political gain.

Manuel A. Alonso

The Jíbaros had a large impact on the culture, the political life, and the language (often mixing in their own words with Spanish) of the Puerto Rican people. However, there were persons who sought to idealize the J�íbaro, such as Manuel A. Alonso. He wrote a novel depicting the conditions of life of the Jíbaro in the first half of the nineteenth century. He wanted to put forth his view of this population. In doing so, he appropriates their culture in a way that twists the image of the Jíbaro. The Jíbaro of Puerto Rico is often seen as the icon of hard work and resilience. However, because of Manuel A. Alonso, the ethno/racial representation of the Jíbaros became closely identified with light skinned and white Puerto Ricans. Consequently, it led to the misconception that the lighter skinned Jíbaros were the essential foundation of the agricultural working class. In actuality, many of them were either mixed race or Afro-Puerto Rican, those in the Cordillera Central on the Northern side particularly in Corozal and Morovis were more white and castizos. [2]

Popular Democratic Party of Puerto Rico

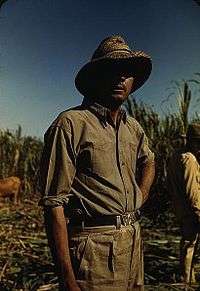

When Luis Muñoz Marín campaigned for a seat in the Puerto Rican Senate, as well as other public offices, he often invoked the Jíbaro as a means of uniting the working class of Puerto Rico under a populist party. To his gain, they came to represent the ideals of hard-working Puerto Ricans. The emblem he created to aid voters in identifying the Popular Democratic Party of Puerto Rico portrayed the Jíbaro as a man with a "pava" (the straw hat that field laborers often wore) with a red background. It served to portray them as a proud people who work and toil in the fields for their bread. Thus, he centered his campaign around the ideals of "Pan, Tierra, Libertad" (Bread, Land, Liberty). Muñoz Marín himself, attempting to further bolster the cause of this party, often dressed like his portrayals of the Jíbaro in an attempt to connect with the working class on a personal level. By idealizing the Jíbaro, Luis Muñoz Marín was also able to court much of the cultural elite of Puerto Rico because many of them thought the Jíbaro to be the "refuge of the Puerto Rican soul". However, his campaign portrayed the Jíbaro through a lens of whiteness, much like Manuel A. Alfonso tried to do.[3]

Historical Roles of the Jíbaro in Revolts and Revolutions

It is noted that many of the struggles against colonial powers involved the Jíbaro population. They were the primary driving force in revolutions such as the one to liberate Puerto Rico from Spanish colonial rule in 1868, the well-known Grito de Lares (Cry of Lares). Even after that revolution failed, the Jíbaro were credited for keeping the spirit of Puerto Rican freedom alive. One final attempt to liberate Puerto Rico from Spain's colonial control was the Intentona de Yauco in 1897. As a result of the Spanish-American War, the Spaniards were forced to cede Puerto Rico by the terms of the Treaty of Paris to the United States which then became the new colonial master. Many Jíbaros organized what were called Bandas Sediciosas (Seditious Bands) to oppose American colonial rule. A few decades later many pro-American mobs had threatened the life of Luis Muñoz Marín, who at the time preferred Puerto Rican independence (eventually, he became the willing collaborator of the American colonialists). Not a few Jíbaro independentista leaders had pledged their support and were willing to march an army of 8,000 guerrilla Jíbaros to defend him, but since he did not want any blood spilled Muñoz Marín refused the offer. Even so, the Jíbaro would continue their struggles against American rule in Puerto Rico such as the armed clashes of members of the Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico with the repressive police forces of the colonial regime in the 1930s and the Nationalist Party revolt in 1950 which was suppressed by American troops. The examples cited herein show that throughout Puerto Rico's history the Jíbaro were committed to freedom no matter how many times they met defeat.[4]

Modern usage of the word

Since at least the 1920s[5] the term "jíbaro" has a more positive connotation in Puerto Rican culture, proudly associated with a cultural ideology as tough pioneers of Puerto Rico.[6]

However, the term occasionally also has a negative connotation. A jíbaro can mean someone who is considered ignorant or impressionable due to a lack of a more European style of education, as are many country or "hillbilly" people of many other cultures.[7] Despite this negative connotation, the image of the jíbaro represents an ideology of a "traditional Puerto Rican": hard-working, simple, independent, and prudently wise.[8]

Colloquially, the jíbaro imagery serves as a representation of the roots of the modern day Puerto Rican people and symbolizes the strength of such traditional values as living simply and properly caring for homeland and family.[8]

Uses of the word in other countries

- In Cuba there exists a word similar to jíbaro, Guajiro. In Cuba and the Dominican Republic a jíbaro can also refer to a runaway dog. This form of use of the word jibaro may had originated from the historical anecdote of jibaro natives running away from the dogs of the "hacendaos", colonial farmers, that has taken the lands of the native jibaros, as it had happen years before during the years of Spaniard Colonization and "encomienda".[9]

- In Colombia, Brazil and Venezuela, Xivaro, or Gibaro, which is pronounced similar to jíbaro, was a name given to the mountain natives of mentioned countries by the Spaniards and Portuguese.[10]

- In Ecuador, givaro is the indomitable indigenous or country persons who are endlessly elusive to the white man.[9]

- In Peru, the word jíbaro refers to country or mountain inhabitants.

- In the 18th century Mexico, a jíbaro was a fable of a child born of a lobo (Wolf) and a china (Chinese), actually that is the child of a mixed-race father (the son of an indigenous man and a black woman) and a mixed-race mother (the daughter of a white man and an indigenous woman).[9]

Further reading

- El Jibaro. Puerto Rico Off The Beaten Path. Page 157. Accessed January 16, 2011.

References

- 1 2 Cruz-Janzen, Marta I. (2003). "Out of the Closet: Racial Amnesia, Avoidance, and Denial - Racism among Puerto Ricans". Race, Gender & Class. 10 (3): 64–81. JSTOR 41675088.

- ↑ Scarano, Francisco A. (1996). "The Jíbaro Masquerade and the Subaltern Politics of Creole Identity Formation in Puerto Rico, 1745-1823". The American Historical Review. 101 (5): 1398–1431. doi:10.2307/2170177. JSTOR 2170177.

- ↑ Cordova, N (2005). "In his image and likeness: The Puerto Rican jíbaro as political icon". Centro Journal. 17 (2): 170–191.

- ↑ Castanha, T (2011). "The Modern Jibaro". The Myth of Indigenous Caribbean Extinction: 89–107.

- ↑ Puerto Rico, Antonio Paoli y España: Aclaraciones y Críticas. Néstor Murray-Irizarry. Footnote #26 (José A. Romeu, "Recordando noches de gloria con el insigne tenor Paoli", El Mundo, 31 de noviembre de 1939. p. 13) Ponce, Puerto Rico. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ↑ ¡Un agricultor de nueve años de edad! Carmen Cila Rodríguez. La Perla del Sur. Ponce, Puerto Rico. 27 July 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- ↑ ""Jibaro". Complimentary or Derogatory?". prezi.com.

- 1 2 ¡Un agricultor de nueve años de edad!: Carlos Emanuel Guzmán, un jíbaro de nueva estirpe. Carmen Cila Rodríguez. La Perla del Sur. Ponce, Puerto Rico. Year 29, Issue 1443. 27 July 2011. Page 6. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- 1 2 3 Enrique Vivoni Farage and Sylvia Álvarez Curbelo. Hispanofilia: Arquitectura y Vida en Puerto Rico, 1900–1950. San Juan, Puerto Rico: Editorial de la Universidad de Puerto Rico. 1998. Page 258. ISBN 0-8477-0252-9.

- ↑ Maurizio Gnerre. Jivaroan linguistic and cultural tradition: an Amazonian-Andean sedimentation (Word Document). Università degli Studi di Pavi

Sources

- Puerto Rico: la gran mentira. 2008. Uahtibili Baez Santiago. Huana Naboli Martinez.