Iñupiat

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 20,709 (2015) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

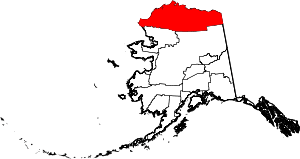

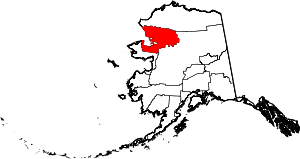

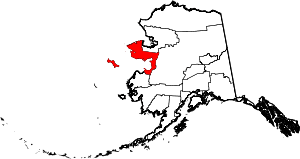

| North and northwest Alaska (United States) | |

| Languages | |

|

North Alaskan Inupiatun, Northwest Alaskan Inupiatun, English[1] | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Animism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Inuit, Yupik |

The Iñupiat (or Inupiaq[2]) are native Alaskan people, whose traditional territory spans Norton Sound on the Bering Sea to the Canada–United States border.[3] Their current communities include seven Alaskan villages in the North Slope Borough, affiliated with the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation; eleven villages in Northwest Arctic Borough; and sixteen villages affiliated with the Bering Straits Regional Corporation.[3]

Name

Iñupiat (IPA: [iɲupiɐt]), formerly Inyupik, is the plural form of the name for the people and the name of their language. The singular form is Iñupiaq (IPA: [iɲupiɑq]}, which also sometimes refers to the language. Iñupiak (IPA: [iɲupiɐk]) is the dual form. The roots are iñuk "person" and -piaq "real", i.e., an endonym meaning "real people".[4][5]

Groups

Ethnic groups

The Iñupiat people are made up of the following communities,

Regional corporations

To equitably manage natural resources, Iñupiat people belong to several of the Alaskan Native Regional Corporations. These are the following.

Languages

Inupiat now speak only two native languages: North Alaskan Inupiat and Northwest Alaskan Inupiat.[1] Many more dialects of these languages flourished prior to contact with European cultures. English is spoken by the Iñupiat because in Native American boarding schools, Iñupiaq children were punished for speaking their own languages.[3]

Several Inupiat people developed pictographic writing systems in the early twentieth century. It is known as Alaskan Picture Writing.[3]

The University of Alaska Fairbanks offers an online course called Beginning Inupiaq Eskimo, an introductory course to the Inupiaq language open to both speakers and non-speakers of Inupiaq.

History

Along with other Inuit groups, the Iñupiaq originate from the Thule culture. Circa 1000 B.C., the Thule migrated from islands in the Bering Sea to what now is Alaska.

Iñupiaq groups, in common with Inuit-speaking groups, often have a name ending in "miut," which means 'a people of'. One example is the Nunamiut, a generic term for inland Iñupiaq caribou hunters. During a period of starvation and an influenza epidemic (likely introduced by American and European whaling crews,[7]) most of these people moved to the coast or other parts of Alaska between 1890 and 1910. A number of Nunamiut returned to the mountains in the 1930s.

By 1950, most Nunamiut groups, such as the Killikmiut, had coalesced in Anaktuvuk Pass, a village in north-central Alaska. Some of the Nunamiut remained nomadic until the 1950s.

The Iditarod Trail's antecedents were the native trails of the Dena'ina and Deg Hit'an Athabaskan Indians and the Inupiaq Eskimos.[8]

Subsistence

.jpg)

Iñupiat people are hunter-gatherers, as are most Arctic peoples. Iñupiat people continue to rely heavily on subsistence hunting and fishing. Depending on their location, they harvest walrus, seal, whale, polar bears, caribou, and fish.[6] Both the inland (Nunamiut) and coastal (Taġiumiut, i.e. Tikiġaġmiut) Iñupiat depend greatly on fish. Throughout the seasons when they are available food staples also include ducks, geese, rabbits, berries, roots, and shoots.

The inland Iñupiat also hunt caribou, dall sheep, grizzly bear, and moose. The coastal Iñupiat hunt walrus, seals, beluga whales, and bowhead whales. Cautiously, polar bear also is hunted.

The capture of a whale benefits each member of an Iñupiat community, as the animal is butchered and its meat and blubber is allocated according to a traditional formula. Even city-dwelling relatives, thousands of miles away, are entitled to a share of each whale killed by the hunters of their ancestral village. Maktak, which is the skin and blubber of Bowhead and other whales, is rich in vitamins A and C.[9][10] The Vitamin C content of meats is destroyed by cooking, so consumption of raw meats and these vitamin-rich foods contributes to good health in a population with limited access to fruits and vegetables.

Since the 1970s, oil and other resources have been an important revenue source for the Iñupiat. The Alaska Pipeline connects the Prudhoe Bay wells with the port of Valdez in south-central Alaska. Because of the oil drilling in Alaska’s arid north, however, the traditional way of whaling is coming into conflict with one of the modern world’s most pressing demands: finding more oil.[11]

The Inupiat eat Ribes triste raw or cooked, mix them with other berries which are used to make a traditional dessert. They also mix the berries with rosehips and highbush cranberries and boil them into a syrup.[12]

Culture

Traditionally, different Iñupiat people lived in sedentary communities, while others were nomadic. Some villages in the area have been occupied by other indigenous groups for more than 10,000 years.

The Nalukataq is a spring whaling festival among Iñupiat.

There is one Iñupiat culture-oriented institute of higher education, Iḷisaġvik College, located in Barrow.

Current issues

Iñupiat people have grown more concerned in recent years that climate change is threatening their traditional lifestyle. The warming trend in the Arctic affects their lifestyle in numerous ways, for example: thinning sea ice makes it more difficult to harvest bowhead whales, seals, walrus, and other traditional foods; warmer winters make travel more dangerous and less predictable; later-forming sea ice contributes to increased flooding and erosion along the coast, directly imperiling many coastal villages. The Inuit Circumpolar Council, a group representing indigenous peoples of the Arctic, has made the case that climate change represents a threat to their human rights.

As of the 2000 U.S. Census, the Iñupiat population in the United States numbered more than 19,000. Most of them live in Alaska.

Iñupiat territories

North Slope Borough : Anaktuvuk Pass (Anaqtuuvak, Naqsraq), Atqasuk (Atqasuk), Barrow (Utqiaġvik, Ukpiaġvik), Kaktovik (Qaagtuviġmiut), Nuiqsut (Nuiqsat), Point Hope (Tikiġaq), Point Lay (Kali), Wainwright (Ulġuniq)

Northwest Arctic Borough : Ambler (Ivisaappaat), Buckland (Nunatchiaq), Deering (Ipnatchiaq), Kiana (Katyaak, Katyaaq), Kivalina (Kivalliñiq), Kobuk (Laugviik), Kotzebue (Qikiqtaġruk), Noatak (Nuataaq ), Noorvik (Nuurvik), Selawik (Siilvik, Akuligaq ), Shungnak (Isiŋnaq, Nuurviuraq)

Nome Census Area : Brevig Mission (Sitaisaq, Sinauraq), Diomede (Inalik), Golovin (Siŋik), Koyuk (Quyuk), Nome (Siqnazuaq), Shaktoolik (Saqtuliq), Shishmaref\ (Qiġiqtaq), Stebbins (Tapqaq), Teller (Tala), Wales (Kiŋigin), White Mountain (Natchirsvik), Unalakleet (Uŋalaqłiq)

Notable Iñupiat

- Ada Blackjack (née Delutuk; 1898 – May 29, 1983) was an Iñupiat woman who lived for two years as a castaway on uninhabited Wrangel Island north of Siberia.

- Edna Ahgeak MacLean (b. 1944), Inupiaq linguist, anthropologist and educator

- Eddie Ahyakak (b. 1977), Iñupiaq marathon runner and expert mountaineer on Season Two on Ultimate Survival Alaska.[13][14]

- Irene Bedard (b. 1967), actress

- Ticasuk Brown (1904–1982), educator, poet and writer

- Charles "Etok" Edwardsen, Jr. (1943-2015), Alaska Native land settlement activist

- Ronald Senungetuk (b. 1933), sculptor, silversmith, educator

See also

- Kivgiq, Messenger Feast

- Maniilaq

- Qargi, men's community house

- Baleen basketry

- Eskimo yo-yo

- Never Alone – a video game featuring Iñupiaq folklore

References

- 1 2 "Inuit-Inupiaq." Ethnologue. Retrieved 4 Dec 2013.

- ↑ Inupiaq [Inupiat] - Alaska Native Cultural Profile

- 1 2 3 4 "Inupiaq (Inupiat)—Alaska Native Cultural Profile." National Network of Libraries of Medicine. Retrieved 4 Dec 2013.

- ↑ Frederick A. Milan (1959), The acculturation of the contemporary Eskimo of Wainwright Alaska

- ↑ Johnson Reprint (1962), Prehistoric cultural relations between the Arctic and Temperate zones of North America

- 1 2 3 "Inupiat." Alaska Native Arts. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ↑ Bockstoce, John (1995). Whales, Ice, & Men: The History of Whaling in the Western Arctic.

- ↑ The Iditarod National Historic Trail/ Seward to Nome Route: A Comprehensive Management Plan, March 1986. Prepared by Bureau of Land Management, Anchorage District Office, Anchorage, Alaska.

- ↑ Geraci, Joseph R.; Smith, Thomas G. (June 1979). "Vitamin C in the Diet of Inuit Hunters From Holman, Northwest Territories" (PDF). Arctic. 32 (2): 135. doi:10.14430/arctic2611.

- ↑ "Vitamin C in Inuit traditional food and women's diets".

- ↑ Mouawad, Jad (December 4, 2007). "In Alaska's Far North, Two Cultures Collide". New York Times.

- ↑ Jones, Anore, 1983, Nauriat Niginaqtuat = Plants That We Eat, Kotzebue, Alaska. Maniilaq Association Traditional Nutrition Program, page 105

- ↑ http://channel.nationalgeographic.com/channel/ultimate-survival-alaska/articles/eddie-ahyakak/

- ↑ "One dead in vehicle collision near North Pole", Alaska Dispatch News, July 29, 2014

Further reading

- Heinrich, Albert Carl. A Summary of Kinship Forms and Terminologies Found Among the Inupiaq Speaking People of Alaska. 1950.

- Sprott, Julie E. Raising Young Children in an Alaskan Iñupiaq Village; The Family, Cultural, and Village Environment of Rearing. West, CT: Bergin & Garvey, 2002. ISBN 0-313-01347-0

- Chance, Norman A. The Eskimo of North Alaska. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1966. ISBN 0-03-057160-X

- Chance, Norman A. The Inupiat and Arctic Alaska: An Ethnology of Development. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1990. ISBN 0-03-032419-X

- Chance, N.A. and Yelena Andreeva. "Sustainability, Equity, and Natural Resource Development in Northwest Siberia and Arctic Alaska." Human Ecology. 1995, vol 23 (2) [June]

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Inupiaq. |