Introduction to genetics

| Part of a series on |

| Genetics |

|---|

|

| Key components |

| History and topics |

| Research |

|

| Personalized medicine |

| Personalized medicine |

|

| Genetics glossary |

|---|

|

They form the rungs of the DNA ladder and are the repeating units in DNA. There are four types of nucleotides (A, T, G and C) and it is the sequence of these nucleotides that carries information. |

|

A package for carrying DNA in the cells. They contain a single long piece of DNA that is wound up and bunched together into a compact structure. Different species of plants and animals have different numbers and sizes of chromosomes. |

|

A segment of DNA. Genes are like sentences made of the "letters" of the nucleotide alphabet, between them genes direct the physical development and behavior of an organism. Genes are like a recipe or instruction book, providing information that an organism needs so it can build or do something - like making an eye or a leg, or repairing a wound. |

|

The different forms of a given gene that an organism may possess. For example, in humans, one allele of the eye-color gene produces green eyes and another allele of the eye-color gene produces brown eyes. |

|

The complete set of genes in a particular organism. |

|

When people change an organism by adding new genes, or deleting genes from its genome. |

|

An event that changes the sequence of the DNA in a gene. |

Genetics is the study of heredity and variations. Heredity and variations are controlled by genes—what they are, what they do, and how they work. Genes inside the nucleus of a cell are strung together in such a way that the sequence carries information: that information determines how living organisms inherit various features (phenotypic traits). For example, offspring produced by sexual reproduction usually look similar to each of their parents because they have inherited some of each of their parents' genes. Genetics identifies which features are inherited, and explains how these features pass from generation to generation. In addition to inheritance, genetics studies how genes are turned on and off to control what substances are made in a cell—gene expression; and how a cell divides—mitosis or meiosis.

Some phenotypic traits can be seen, such as eye color while others can only be detected, such as blood type or intelligence. Traits determined by genes can be modified by the animal's surroundings (environment): for example, the general design of a tiger's stripes is inherited, but the specific stripe pattern is determined by the tiger's surroundings. Another example is a person's height: it is determined by both genetics and nutrition.

Chromosomes are tiny packages which contain one DNA molecule and its associated proteins. Humans have 46 chromosomes (23 pairs). This number varies between species—for example, many primates have 24 pairs. Meiosis creates special cells, sperm in males and eggs in females, which only have 23 chromosomes. These two cells merge into one during the fertilization stage of sexual reproduction, creating a zygote. In a zygote, a nucleic acid double helix divides, with each single helix occupying one of the daughter cells, resulting in half the normal number of genes. By the time the zygote divides again, genetic recombination has created a new embryo with 23 pairs of chromosomes, half from each parent. Mating and resultant mate choice result in sexual selection. In normal cell division (mitosis) is possible when the double helix separates, and a complement of each separated half is made, resulting in two identical double helices in one cell, with each occupying one of the two new daughter cells created when the cell divides.

Chromosomes all contain DNA made up of four nucleotides, abbreviated C (cytosine), G (guanine), A (adenine), or T (thymine), which line up in a particular sequence and make a long string. There are two strings of nucleotides coiled around one another in each chromosome: a double helix. C on one string is always opposite from G on the other string; A is always opposite T. There are about 3.2 billion nucleotide pairs on all the human chromosomes: this is the human genome. The order of the nucleotides carries genetic information, whose rules are defined by the genetic code, similar to how the order of letters on a page of text carries information. Three nucleotides in a row—a triplet—carry one unit of information: a codon.

The genetic code not only controls inheritance: it also controls gene expression, which occurs when a portion of the double helix is uncoiled, exposing a series of the nucleotides, which are within the interior of the DNA. This series of exposed triplets (codons) carries the information to allow machinery in the cell to "read" the codons on the exposed DNA, which results in the making of RNA molecules. RNA in turn makes either amino acids or microRNA, which are responsible for all of the structure and function of a living organism; i.e. they determine all the features of the cell and thus the entire individual. Closing the uncoiled segment turns off the gene.

The heritability of a trait (like height) in a population essentially conveys what percentage of the observed variation comes from differences in genes vs. differences in environment. Each unique form of a single gene is called an allele; different forms are collectively called polymorphisms. As an example, one allele for the gene for hair color and skin cell pigmentation could instruct the body to produce black pigment, producing black hair and pigmented skin; while a different allele of the same gene in a different individual could give garbled instructions that would result in a failure to produce any pigment, giving white hair and no pigmented skin: albinism. Mutations are random changes in genes creating new alleles, which in turn produce new traits, which could help, harm, or have no new effect on the individual's likelihood of survival; thus, mutations are the basis for evolution.

Inheritance in biology

Genes and inheritance

Genes are pieces of DNA that contain information for synthesis of ribonucleic acids (RNAs) or polypeptides. Genes are inherited as units, with two parents dividing out copies of their genes to their offspring. This process can be compared with mixing two hands of cards, shuffling them, and then dealing them out again. Humans have two copies of each of their genes, and make copies that are found in eggs or sperm—but they only include one copy of each type of gene. An egg and sperm join to form a complete set of genes. The eventually resulting offspring has the same number of genes as their parents, but for any gene one of their two copies comes from their father, and one from their mother.[1]

The effects of this mixing depend on the types (the alleles) of the gene. If the father has two copies of an allele for red hair, and the mother has two copies for brown hair, all their children get the two alleles that give different instructions, one for red hair and one for brown. The hair color of these children depends on how these alleles work together. If one allele dominates the instructions from another, it is called the dominant allele, and the allele that is overridden is called the recessive allele. In the case of a daughter with alleles for both red and brown hair, brown is dominant and she ends up with brown hair.[2]

Although the red color allele is still there in this brown-haired girl, it doesn't show. This is a difference between what you see on the surface (the traits of an organism, called its phenotype) and the genes within the organism (its genotype). In this example you can call the allele for brown "B" and the allele for red "b". (It is normal to write dominant alleles with capital letters and recessive ones with lower-case letters.) The brown hair daughter has the "brown hair phenotype" but her genotype is Bb, with one copy of the B allele, and one of the b allele.

Now imagine that this woman grows up and has children with a brown-haired man who also has a Bb genotype. Her eggs will be a mixture of two types, one sort containing the B allele, and one sort the b allele. Similarly, her partner will produce a mix of two types of sperm containing one or the other of these two alleles. When the transmitted genes are joined up in their offspring, these children have a chance of getting either brown or red hair, since they could get a genotype of BB = brown hair, Bb = brown hair or bb = red hair. In this generation, there is therefore a chance of the recessive allele showing itself in the phenotype of the children—some of them may have red hair like their grandfather.[2]

Many traits are inherited in a more complicated way than the example above. This can happen when there are several genes involved, each contributing a small part to the end result. Tall people tend to have tall children because their children get a package of many alleles that each contribute a bit to how much they grow. However, there are not clear groups of "short people" and "tall people", like there are groups of people with brown or red hair. This is because of the large number of genes involved; this makes the trait very variable and people are of many different heights.[3] Despite a common misconception, the green/blue eye traits are also inherited in this complex inheritance model.[4] Inheritance can also be complicated when the trait depends on interaction between genetics and environment. For example, malnutrition does not change traits like eye color, but can stunt growth.[5]

Inherited diseases

Some diseases are hereditary and run in families; others, such as infectious diseases, are caused by the environment. Other diseases come from a combination of genes and the environment.[6] Genetic disorders are diseases that are caused by a single allele of a gene and are inherited in families. These include Huntington's disease, Cystic fibrosis or Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cystic fibrosis, for example, is caused by mutations in a single gene called CFTR and is inherited as a recessive trait.[7]

Other diseases are influenced by genetics, but the genes a person gets from their parents only change their risk of getting a disease. Most of these diseases are inherited in a complex way, with either multiple genes involved, or coming from both genes and the environment. As an example, the risk of breast cancer is 50 times higher in the families most at risk, compared to the families least at risk. This variation is probably due to a large number of alleles, each changing the risk a little bit.[8] Several of the genes have been identified, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2, but not all of them. However, although some of the risk is genetic, the risk of this cancer is also increased by being overweight, drinking a lot of alcohol and not exercising.[9] A woman's risk of breast cancer therefore comes from a large number of alleles interacting with her environment, so it is very hard to predict.

How genes work

Genes make proteins

The function of genes is to provide the information needed to make molecules called proteins in cells.[1] Cells are the smallest independent parts of organisms: the human body contains about 100 trillion cells, while very small organisms like bacteria are just one single cell. A cell is like a miniature and very complex factory that can make all the parts needed to produce a copy of itself, which happens when cells divide. There is a simple division of labor in cells—genes give instructions and proteins carry out these instructions, tasks like building a new copy of a cell, or repairing damage.[10] Each type of protein is a specialist that only does one job, so if a cell needs to do something new, it must make a new protein to do this job. Similarly, if a cell needs to do something faster or slower than before, it makes more or less of the protein responsible. Genes tell cells what to do by telling them which proteins to make and in what amounts.

Proteins are made of a chain of 20 different types of amino acid molecules. This chain folds up into a compact shape, rather like an untidy ball of string. The shape of the protein is determined by the sequence of amino acids along its chain and it is this shape that, in turn, determines what the protein does.[10] For example, some proteins have parts of their surface that perfectly match the shape of another molecule, allowing the protein to bind to this molecule very tightly. Other proteins are enzymes, which are like tiny machines that alter other molecules.[11]

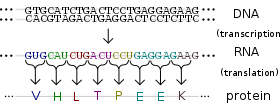

The information in DNA is held in the sequence of the repeating units along the DNA chain.[12] These units are four types of nucleotides (A,T,G and C) and the sequence of nucleotides stores information in an alphabet called the genetic code. When a gene is read by a cell the DNA sequence is copied into a very similar molecule called RNA (this process is called transcription). Transcription is controlled by other DNA sequences (such as promoters), which show a cell where genes are, and control how often they are copied. The RNA copy made from a gene is then fed through a structure called a ribosome, which translates the sequence of nucleotides in the RNA into the correct sequence of amino acids and joins these amino acids together to make a complete protein chain. The new protein then folds up into its active form. The process of moving information from the language of RNA into the language of amino acids is called translation.[13]

If the sequence of the nucleotides in a gene changes, the sequence of the amino acids in the protein it produces may also change—if part of a gene is deleted, the protein produced is shorter and may not work any more.[10] This is the reason why different alleles of a gene can have different effects in an organism. As an example, hair color depends on how much of a dark substance called melanin is put into the hair as it grows. If a person has a normal set of the genes involved in making melanin, they make all the proteins needed and they grow dark hair. However, if the alleles for a particular protein have different sequences and produce proteins that can't do their jobs, no melanin is produced and the person has white skin and hair (albinism).[14]

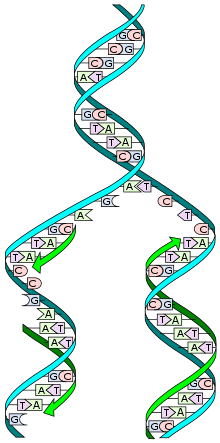

Genes are copied

Genes are copied each time a cell divides into two new cells. The process that copies DNA is called DNA replication.[12] It is through a similar process that a child inherits genes from its parents, when a copy from the mother is mixed with a copy from the father.

DNA can be copied very easily and accurately because each piece of DNA can direct the creation of a new copy of its information. This is because DNA is made of two strands that pair together like the two sides of a zipper. The nucleotides are in the center, like the teeth in the zipper, and pair up to hold the two strands together. Importantly, the four different sorts of nucleotides are different shapes, so for the strands to close up properly, an A nucleotide must go opposite a T nucleotide, and a G opposite a C. This exact pairing is called base pairing.[12]

When DNA is copied, the two strands of the old DNA are pulled apart by enzymes; then they pair up with new nucleotides and then close. This produces two new pieces of DNA, each containing one strand from the old DNA and one newly made strand. This process is not predictably perfect as proteins attach to a nucleotide while they are building and cause a change in the sequence of that gene. These changes in DNA sequence are called mutations.[15] Mutations produce new alleles of genes. Sometimes these changes stop the functioning of that gene or make it serve another advantageous function, such as the melanin genes discussed above. These mutations and their effects on the traits of organisms are one of the causes of evolution.[16]

Genes and evolution

A population of organisms evolves when an inherited trait becomes more common or less common over time.[16] For instance, all the mice living on an island would be a single population of mice: some with white fur, some gray. If over generations, white mice became more frequent and gray mice less frequent, then the color of the fur in this population of mice would be evolving. In terms of genetics, this is called an increase in allele frequency.

Alleles become more or less common either by chance in a process called genetic drift, or by natural selection.[17] In natural selection, if an allele makes it more likely for an organism to survive and reproduce, then over time this allele becomes more common. But if an allele is harmful, natural selection makes it less common. In the above example, if the island were getting colder each year and snow became present for much of the time, then the allele for white fur would favor survival, since predators would be less likely to see them against the snow, and more likely to see the gray mice. Over time white mice would become more and more frequent, while gray mice less and less.

Mutations create new alleles. These alleles have new DNA sequences and can produce proteins with new properties.[18] So if an island was populated entirely by black mice, mutations could happen creating alleles for white fur. The combination of mutations creating new alleles at random, and natural selection picking out those that are useful, causes adaptation. This is when organisms change in ways that help them to survive and reproduce. Many such changes, studied in evolutionary developmental biology, affect the way the embryo develops into an adult body.

Genetic engineering

Since traits come from the genes in a cell, putting a new piece of DNA into a cell can produce a new trait. This is how genetic engineering works. For example, rice can be given genes from a maize and a soil bacteria so the rice produces beta-carotene, which the body converts to Vitamin A.[19] This can help children suffering from Vitamin A deficiency. Another gene being put into some crops comes from the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis; the gene makes a protein that is an insecticide. The insecticide kills insects that eat the plants, but is harmless to people.[20] In these plants, the new genes are put into the plant before it is grown, so the genes are in every part of the plant, including its seeds.[21] The plant's offspring inherit the new genes, which has led to concern about the spread of new traits into wild plants.[22]

The kind of technology used in genetic engineering is also being developed to treat people with genetic disorders in an experimental medical technique called gene therapy.[23] However, here the new gene is put in after the person has grown up and become ill, so any new gene is not inherited by their children. Gene therapy works by trying to replace the allele that causes the disease with an allele that works properly.

See also

References

- 1 2 University of Utah Genetics Learning Center animated tour of the basics of genetics. Howstuffworks.com. Archived from the original on 10 February 2008. Retrieved 24 January 2008.

- 1 2 MELANOCORTIN 1 RECEPTOR, Accessed 27 November 2010

- ↑ Multifactorial Inheritance Health Library, Morgan Stanley Children's Hospital, Accessed 20 May 2008

- ↑ Eye color is more complex than two genes, Athro Limited, Accessed 27 November 2010

- ↑ "Low income kids' height doesn't measure up by age 1". University of Michigan Health System. Archived from the original on 26 May 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ↑ requently Asked Questions About Genetic Disorders NIH, Accessed 20 May 2008

- ↑ Cystic fibrosis Genetics Home Reference, NIH, Accessed 16 May 2008

- ↑ Peto J (June 2002). "Breast cancer susceptibility-A new look at an old model". Cancer Cell. 1 (5): 411–2. doi:10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00079-X. ISSN 1535-6108. PMID 12124169.

- ↑ What Are the Risk Factors for Breast Cancer? Archived 29 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine. American Cancer Society, Accessed 16 May 2008

- 1 2 3 The Structures of Life National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Accessed 20 May 2008

- ↑ Enzymes HowStuffWorks, Accessed 20 May 2008

- 1 2 3 What is DNA? Genetics Home Reference, Accessed 16 May 2008

- ↑ DNA-RNA-Protein Nobelprize.org, Accessed 20 May 2008

- ↑ What is Albinism? The National Organization for Albinism and Hypopigmentation, Accessed 20 May 2008

- ↑ Mutations Archived 15 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine. The University of Utah, Genetic Science Learning Center, Accessed 20 May 2008

- 1 2 Brain, Marshall. "How Evolution Works". How Stuff Works: Evolution Library. Howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

- ↑ Mechanisms: The Processes of Evolution Archived 27 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Understanding Evolution, Accessed 20 May 2008

- ↑ Genetic Variation Archived 27 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Understanding Evolution, Accessed 20 May 2008

- ↑ Staff Golden Rice Project Retrieved 5 November 2012

- ↑ Tifton, Georgia: A Peanut Pest Showdown USDA, accessed 16 May 2008

- ↑ Genetic engineering: Bacterial arsenal to combat chewing insects GMO Safety, Jul 2010

- ↑ Genetically engineered organisms public issues education Cornell University, Accessed 16 May 2008

- ↑ Staff (November 18, 2005). "Gene Therapy" (FAQ). Human Genome Project Information. Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Retrieved 2006-05-28.

External links

| Wikiversity has learning resources about Genetics |

- Introduction to Genetics, University of Utah

- Introduction to Genes and Disease, NCBI open book

- Genetics glossary, A talking glossary of genetic terms.

- Animated guide to cloning

- Khan Academy on YouTube

- What Color Eyes Would Your Children Have? Genetics of human eye color: An interactive introduction

- Double Helix Game from the Nobel Prize website. Match CATG bases with each other, and other games

- Transcribe and translate a gene, University of Utah

- StarGenetics software simulates mating experiments between organisms that are genetically different across a range of traits