Intelligent agent

In artificial intelligence, an intelligent agent (IA) is an autonomous entity which observes through sensors and acts upon an environment using actuators (i.e. it is an agent) and directs its activity towards achieving goals (i.e. it is "rational", as defined in economics[1]). Intelligent agents may also learn or use knowledge to achieve their goals. They may be very simple or very complex. A reflex machine, such as a thermostat, is considered an example of an intelligent agent.[2]

Intelligent agents are often described schematically as an abstract functional system similar to a computer program. For this reason, intelligent agents are sometimes called abstract intelligent agents (AIA) to distinguish them from their real world implementations as computer systems, biological systems, or organizations. Some definitions of intelligent agents emphasize their autonomy, and so prefer the term autonomous intelligent agents. Still others (notably Russell & Norvig (2003)) considered goal-directed behavior as the essence of intelligence and so prefer a term borrowed from economics, "rational agent".

Intelligent agents in artificial intelligence are closely related to agents in economics, and versions of the intelligent agent paradigm are studied in cognitive science, ethics, the philosophy of practical reason, as well as in many interdisciplinary socio-cognitive modeling and computer social simulations.

Intelligent agents are also closely related to software agents (an autonomous computer program that carries out tasks on behalf of users). In computer science, the term intelligent agent may be used to refer to a software agent that has some intelligence, regardless if it is not a rational agent by Russell and Norvig's definition. For example, autonomous programs used for operator assistance or data mining (sometimes referred to as bots) are also called "intelligent agents".

A variety of definitions

Intelligent agents have been defined many different ways.[3] According to Nikola Kasabov[4] AI systems should exhibit the following characteristics:

- Accommodate new problem solving rules incrementally

- Adapt online and in real time

- Are able to analyze themselves in terms of behavior, error and success.

- Learn and improve through interaction with the environment (embodiment)

- Learn quickly from large amounts of data

- Have memory-based exemplar storage and retrieval capacities

- Have parameters to represent short and long term memory, age, forgetting, etc.

Structure of agents

A simple agent program can be defined mathematically as an agent function[5] which maps every possible percepts sequence to a possible action the agent can perform or to a coefficient, feedback element, function or constant that affects eventual actions:

Agent function is an abstract concept as it could incorporate various principles of decision making like calculation of utility of individual options, deduction over logic rules, fuzzy logic, etc.[6]

The program agent, instead, maps every possible percept to an action.

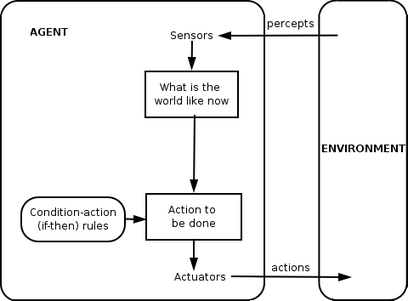

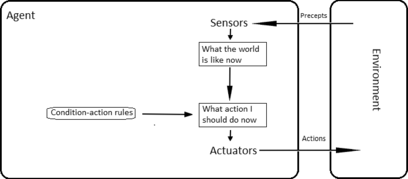

We use the term percept to refer to the agent's perceptional inputs at any given instant. In the following figures an agent is anything that can be viewed as perceiving its environment through sensors and acting upon that environment through actuators.

Architectures

Weiss (2013) said we should consider four classes of agents:

- Logic-based agents – in which the decision about what action to perform is made via logical deduction;

- Reactive agents – in which decision making is implemented in some form of direct mapping from situation to action;

- Belief-desire-intention agents – in which decision making depends upon the manipulation of data structures representing the beliefs, desires, and intentions of the agent; and finally,

- Layered architectures – in which decision making is realized via various software layers, each of which is more or less explicitly reasoning about the environment at different levels of abstraction.

Classes

Russell & Norvig (2003) group agents into five classes based on their degree of perceived intelligence and capability:[7]

- simple reflex agents

- model-based reflex agents

- goal-based agents

- utility-based agents

- learning agents

Simple reflex agents

Simple reflex agents act only on the basis of the current percept, ignoring the rest of the percept history. The agent function is based on the condition-action rule: if condition then action.

This agent function only succeeds when the environment is fully observable. Some reflex agents can also contain information on their current state which allows them to disregard conditions whose actuators are already triggered.

Infinite loops are often unavoidable for simple reflex agents operating in partially observable environments. Note: If the agent can randomize its actions, it may be possible to escape from infinite loops.

Model-based reflex agents

A model-based agent can handle partially observable environments. Its current state is stored inside the agent maintaining some kind of structure which describes the part of the world which cannot be seen. This knowledge about "how the world works" is called a model of the world, hence the name "model-based agent".

A model-based reflex agent should maintain some sort of internal model that depends on the percept history and thereby reflects at least some of the unobserved aspects of the current state. Percept history and impact of action on the environment can be determined by using internal model. It then chooses an action in the same way as reflex agent.

An agent may also use models to describe and predict the behaviors of other agents in the environment.[8]

Goal-based agents

Goal-based agents further expand on the capabilities of the model-based agents, by using "goal" information. Goal information describes situations that are desirable. This allows the agent a way to choose among multiple possibilities, selecting the one which reaches a goal state. Search and planning are the subfields of artificial intelligence devoted to finding action sequences that achieve the agent's goals.

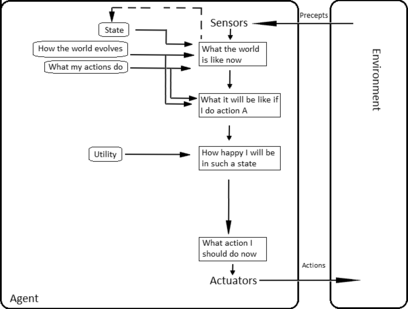

Utility-based agents

Goal-based agents only distinguish between goal states and non-goal states. It is possible to define a measure of how desirable a particular state is. This measure can be obtained through the use of a utility function which maps a state to a measure of the utility of the state. A more general performance measure should allow a comparison of different world states according to exactly how happy they would make the agent. The term utility can be used to describe how "happy" the agent is.

A rational utility-based agent chooses the action that maximizes the expected utility of the action outcomes - that is, what the agent expects to derive, on average, given the probabilities and utilities of each outcome. A utility-based agent has to model and keep track of its environment, tasks that have involved a great deal of research on perception, representation, reasoning, and learning.

Learning agents

Learning has the advantage that it allows the agents to initially operate in unknown environments and to become more competent than its initial knowledge alone might allow. The most important distinction is between the "learning element", which is responsible for making improvements, and the "performance element", which is responsible for selecting external actions.

The learning element uses feedback from the "critic" on how the agent is doing and determines how the performance element should be modified to do better in the future. The performance element is what we have previously considered to be the entire agent: it takes in percepts and decides on actions.

The last component of the learning agent is the "problem generator". It is responsible for suggesting actions that will lead to new and informative experiences.

Hierarchies of agents

To actively perform their functions, Intelligent Agents today are normally gathered in a hierarchical structure containing many “sub-agents”. Intelligent sub-agents process and perform lower level functions. Taken together, the intelligent agent and sub-agents create a complete system that can accomplish difficult tasks or goals with behaviors and responses that display a form of intelligence.

Applications

Intelligent agents are applied as automated online assistants, where they function to perceive the needs of customers in order to perform individualized customer service. Such an agent may basically consist of a dialog system, an avatar, as well an expert system to provide specific expertise to the user.[9] They can also be used to optimize coordination of human groups online.[10]

See also

- Software agent

- Cognitive architectures

- Cognitive radio – a practical field for implementation

- Cybernetics, Computer science

- Data mining agent

- Embodied agent

- Federated search – the ability for agents to search heterogeneous data sources using a single vocabulary

- Fuzzy agents – IA implemented with adaptive fuzzy logic

- GOAL agent programming language

- Intelligence

- Intelligent system

- JACK Intelligent Agents

- Multi-agent system and multiple-agent system – multiple interactive agents

- PEAS classification of an agent's environment

- Reinforcement learning

- Semantic Web – making data on the Web available for automated processing by agents

- Simulated reality

- Social simulation

- Era of intelligent agents

Notes

- ↑ Russell & Norvig 2003, chpt. 2

- ↑ According to the definition given by Russell & Norvig (2003, chpt. 2)

- ↑ Some definitions are examined by Franklin & Graesser 1996 and Kasabov 1998.

- ↑ Kasabov 1998

- ↑ Russell & Norvig 2003, p. 33

- ↑ Salamon, Tomas (2011). Design of Agent-Based Models. Repin: Bruckner Publishing. pp. 42–59. ISBN 978-80-904661-1-1.

- ↑ Russell & Norvig 2003, pp. 46–54

- ↑ S.V. Albrecht and P. Stone (2018). Autonomous Agents Modelling Other Agents: A Comprehensive Survey and Open Problems. Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 258, pp. 66-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artint.2018.01.002

- ↑ Providing Language Instructor with Artificial Intelligence Assistant. By Krzysztof Pietroszek. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), Vol 2, No 4 (2007) "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-03-07. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ↑ Shirado, Hirokazu; Christakis, Nicholas A. "Locally noisy autonomous agents improve global human coordination in network experiments". Nature. 545 (7654): 370–374. doi:10.1038/nature22332.

References

- Russell, Stuart J.; Norvig, Peter (2003), Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (2nd ed.), Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-790395-2 , chpt. 2

- Stan Franklin and Art Graesser (1996); Is it an Agent, or just a Program?: A Taxonomy for Autonomous Agents; Proceedings of the Third International Workshop on Agent Theories, Architectures, and Languages, Springer-Verlag, 1996

- N. Kasabov, Introduction: Hybrid intelligent adaptive systems. International Journal of Intelligent Systems, Vol.6, (1998) 453–454.

- Weiss, G. (2013). Multiagent systems (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.