Informing science

Informing science is a transdiscipline that was established to promote the study of informing processes across a diverse set of academic disciplines, including management information systems, education, business, instructional technology, computer science, communications, psychology, philosophy, library science, information science and many others. Its principal unit of analysis is the informing system, a collection of informers, clients and channels that has been designed or has evolved to serve a particular informing need. The organization created to advance the informing science transdiscipline is the Informing Science Institute (ISI), whose founder, Eli Cohen, proposed the need for field in his article "Reconceptualizing Information Systems as a Field of the Transdiscipline Informing Science: From Ugly Duckling to Swan" (Cohen, 1999). The ISI presently host an annual conference (Informing Science & Information Technology Education (InSITE)), publishes seven academic journals, and—through its Informing Science Press—has published for dozens of books. Both its journals and books are open access at no cost online, as well as being available for purchase in print form.

History

Informing science came into being as a transdiscipline around 1998. During that year, two key events occurred. The seminal article that defined the field (Cohen, 1999) was accepted for publication and the field's flagship journal--Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline—was launched.

The theme of Cohen's (1999) article was relatively simple, and resonated with many in the global academic community. In brief, he argued that many different disciplines are studying the same types of issues: teaching programming, communicating effectively, designing systems to provide information to clients, and so forth, as illustrated in Table 1. This situation was not only inefficient from a research standpoint, but it also tended to promote research silos in which researchers from one discipline were unable to benefit from the research of colleagues in other disciplines. In the long run, he asserted that such a situation would be highly deleterious to our overall understanding of these processes. He expressed particular concern with the situation in his own research discipline, management information systems, which was already becoming fragmented and increasingly irrelevant to practice.

| Informing Discipline | Client to be Informed |

| Information Systems | Workers in a Firm, Managers |

| Information Science | Library patron |

| Journalism | Reader/Viewer/Listener |

| Public Relations | Public |

| Secretarial/Office Systems | Office Workers |

What Cohen proposed as an antidote to this situation was the establishment of an interdisciplinary community of researchers described as follows:

- The fields that comprise the discipline of Informing Science provide their clientele with information in a form, format and schedule that maximizes its effectiveness (Cohen, 1999, p. 215)

During its earliest years, the informing science discipline was particularly focused on issues related to management information systems and information/library science—the fields from which many of its researchers originated. Over time, however, instructional technology became an important area of research, leading to the establishment of additional journals in the informing science in the education and instructional technology areas. In recent years, an effort has been made to further broaden the field. In 2009, the collection Foundations of Informing Science (Gill & Cohen, 2009) was published, including both seminal articles from its journals and new contributions. The collection included chapters related to economics, decision theory, political science, education, design, complexity science and mining. Currently, the informing science field is encouraging interest in research that is not necessarily related to technology. In a recent keynote address given at InSITE 2011 by T. Grandon Gill, the editor-in-chief of the journal Informing Science proposed that the field could be described as follows:

- Informing Science is the transdisciplinary study of systems that employ information to impact clientele

In that same address, a number of areas meriting additional research were proposed. These included:

- Greater emphasis on informing systems that evolve, as opposed to those that are created by design

- Study of informing through non-symbolic means, such as body language and music, as well as through language and the exchange of coded data

- Paying greater attention to the topologies of informing systems as opposed to emphasizing Sender → Receiver communications models whose roots go back to Claude Shannon (Shannon & Weaver, 1949)

- Obstacles to informing, such as bias and heuristics, that are particularly challenging when human clients are involved

- The relationship of informing systems structure and the complexity of the message being conveyed

Informing Systems

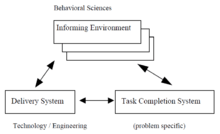

The basic unit of analysis for informing science is the informing system. According to the original Cohen (1999) article, such systems consist of three components: an informing environment, a delivery system and a task completion system, as shown in Figure 1:

The delivery system represented the combination of technological and non-technological elements that comprised the communications channel. The informing environment represented the system components of the system on the informer's (sender's) side. The task completion system involved the components of the system related to the client (user, receiver) of the information. This particular conception, illustrated in Figure 2, allowed the model map well to Shannon's communication model.

Topology of Informing Systems

While the basic model did, and still does, serve as a useful unit of analysis, it was pointed out that "real world" informing systems come in many topologies, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Among the variations of systems listed are the following (Gill & Bhattacherjee, 2007, p. 19):

- Sender and client components are rarely homogeneous. Rather, senders consist of complex informing environments that involve subsystems that may, themselves, be informing systems. The same can be said of clients...

- Senders may be members of multiple informing systems that inform different clients. Drucker (1989), for example, refers to the inherent tension that knowledge workers experience as they divide their loyalties between profession (e.g., accounting, law, medicine) and the organization that employs them.

- Multiple senders may compete to inform the same client. For example different departments(disciplines) may compete for the same set of students; doctors from different specialties may compete to diagnose the same patients, etc.

- Multiple communications pathways may be utilized within the same informing system. For example, an advertising campaign may involve the use of print, broadcast and web-based media in order to reach its entire client base.

- Multiple clients may be informed by the same sender, and may have to compete for that sender's attention. For example, a patient may find his or her case is neglected as a consequence of the attention a doctor pays to the needs of other patients.

- Clients may, themselves, serve as part of an extended informing system. For example, a company may depend heavily on "word of mouth" advertising to gain new clients.

Construction of Informing Systems

Given the field's origins in management information systems (MIS) research, it is not unexpected that early investigations into, and conceptualizations of, the development of informing systems tended to rely heavily on technology-based experienced. Cohen (1999), for example, viewed informing systems as having three levels:

- The informing instance level, where actual informing activities took place.

- The construction level, at which new informing instances were created according to the prevailing design templates.

- The design level, at which new architectures for informing were realized.

As examples, he proposed (Cohen, 1999, p. 217):

- (1) teaching a course someone else has designed, (2) designing a course that will be taught by others, and (3) creating a new curriculum. A business example is (1) using an existing transaction processing system (TPS), (2) creating a TPS following general design rules, and (3) creating a new type of TPS.

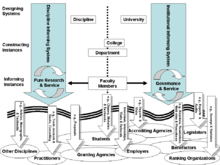

As illustrated in Figure 4, Gill and Bhattacherjee (2007) further expanded the concept with the example of academic informing systems, which can be described in terms of two related informing systems that share many of the same clients. The disciplinary system represents the research field with which faculty members and departments are aligned. The institutional system represents the activities of the college or university, primarily focused on informing student clients. In subsequent publications (e.g., Gill, 2009a), informing science researchers have also begun to address the issue of how such systems can evolve, as opposed to being a pure product of design. The importance of understanding these informal processes for informing system development—even for IT-based systems—has been underscored by the rapid acceptance of technologies such as social media. There is little question that users have adapted these technologies for their own informing purposes in ways far beyond those anticipated by the original designers of the systems.

Informing Science Research

In informing science, the term transdiscipline refers to the idea that a common problem—in this case the challenges presented by informing--may benefit from the diversity of insights and perspectives offered by multiple disciplines, sometimes referred to as the component disciplines or client disciplines of informing science. To foster such a collaboration among researchers, however, requires extending the notion of what constitutes "research". It has also led to the development of a number of parallel research streams.

Extending the Definition of Research

In an open letter to the informing science community describing the types of research appropriate for the field, the Editor-in-Chief of Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline T. Grandon Gill made the following statement (Gill, 2009b, p. vi):

- The transdisciplinary character of InformSciJ requires that we be willing to publish a broad array of contributions. In many of our client fields, most published research contributions can be characterized as either theory-building or theory-testing. While submissions of this type are, of course, encouraged, we will also consider a broader range of contributions, including:

- Synthesis: An existing body of theory and observations are organized into a more cohesive whole. A literature review may fall into this category, but only if it attempts to propose a novel systematic organization for the existing literature.

- Illustration: The meaning or implications of a particular theory are explained and clarified through an illustrative example. In the business literature, for example, nearly all practitioner-directed publications use this technique extensively.

- Unexplained Observation: A rich observation, often having properties not well explained with existing theory, that is offered without serious attempt to incorporate it into theory. It is interesting to note that while research of the form “I observed this but I can’t explain it” would be nearly impossible to publish in any social science journal known to me, such anomalous observations often form the basis for scientific revolution (Kuhn, 1970)—such as the Michelson Morley experiment, which paved the way for Einstein’s special relativity.

- We must never forget that our transdisciplinary mission demands that we view facilitating informing across the client disciplines as an important form of research. Providing a reader in one discipline with a novel perspective—even if that perspective is not necessarily novel in the discipline of the author—is a necessary part of transdisciplinary knowledge creation.

As a consequence of this expanded view of research, the journals and conferences sponsored by the ISI cover a very broad array of topics, research methods and styles of presentation.

Research Themes in Informing Science

Although much of the research in informing science does not fit within simple categories, there have been a number of themes that have captured the particular interest of researchers in the field. These include:

- The nature of information and informing: Beginning with a special issue on information science research (Spink, 2000), the ambiguity associated with the use of terms such as information, data and knowledge in different disciplines has been a frequent topic (e.g., Callaos & Callaos, 2002; Knox, 2009).

- The nature of complexity and its impact on informing: Efforts have been made both to define complexity more clearly (e.g., Gill & Hicks, 2006) and to better understand its impact on informing processes (e.g., Gill & Cohen, 2008).

- Bridging the gap between research a practice: Launched by another special issue (Fitzgerald, 2003), this topic of why academic research is so often ignored by practice has been frequently explored (e.g. Gill & Bhattacherjee, 2007) and is one where the informing science perspective has also started to gain practice in client disciplines (e.g., Myers et al., 2011).

- The impact of content delivery (e.g., multimedia, web) on informing processes: Examples include investigations of multimedia (e.g., Sharda, 2005), eLearning (e.g., Sarker & Nicholson, 2005) and adapting channels to highly restrictive informing environments (e.g., Spasic & Nesic, 2009).

- Impact of bias, misinformation and disinformation on informing processes: Both theoretical and practical research has been devoted to understanding the role played by bias (e.g., Jamieson & Hyland, 2006), misinformation (Bednar and Welch, 2008; Christozov, Chukova and Mateev, 2009) and deception (e.g., Hutchinson, 2006) in informing processes.

- The role of adaptation in informing system design and construction: Moving away from traditional MIS design models, such as the systems development lifecycle (SDLC), researchers have proposed drawing upon alternative metaphors, such as the double helix (e.g., Nissen, Bednar, & Welch, 2007), co-evolution (e.g., Pahl & Newnes, 2007), approaches grounded in philosophy (e.g., Bednar & Welch, 2009), and integrationist approaches such as the informing view of organization that bridges the MIS, and organization theory (Travica, 2014).

- The need to broaden approaches to research within client disciplines: Noting that positivist, empirical research methods do not necessarily yield useful results in many client disciplines, many researchers have proposed alternative approaches (e.g., Mende, 2005; Gill, 2011).

Consistent with its roots in the MIS and education client disciplines, many articles published in Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline represent the types of research that might also be publishable within the client disciplines themselves. By 2010, however, the editorial policy had evolved. The Editor-in-Chief of the journal commented on the current state of policy in the following statement (Gill, 2010, p. v):

- We also continue to publish work from many different disciplines and, particularly welcome, see that many of our articles represent collaborations between authors coming from different disci-plines. Such broad representation and collaboration is the lifeblood of a transdiscipline. It is all too easy for a journal to gravitate towards a particular perspective on research. It is heartening to see that the authors submitting their work to InformSciJ are resisting that tendency.

- I am also happy to report that the linkage between our research and the general problem of “informing” has grown much tighter over the past two years. While there was a time when Inform-SciJ would publish almost any high quality submission from its contributing disciplines (e.g., MIS, education, communications, philosophy, instructional technology), that is no longer the case. Today, every article we publish identifies how its topic relates to informing. I will admit that, in the past, I have been somewhat heavy-handed in enforcing that such a linkage be present. Recently, however, I have found authors increasingly taking it upon themselves to relate their findings to informing without my intervention. While the journal has missed the opportunity to publish some excellent work as a result, I am convinced that our long term interests are best served by being true to the central problem that we are studying.

As a consequence of the gradual adoption of this policy, recent volumes of the journal have become both slimmer and size and more directly focused on the journal's mission.

Informing Science Institute

The principal organizing body for the informing science transdiscipline is the Informing Science Institute (ISI). According to a recently published article (Murphy, 2011, p. 91):

- Since its inception, it has published approximately 1,000 articles by over 1,000 authors from over 500 universities all across the globe

In that same article, the ISI's activities were described in informing system terms. These are illustrated in Figure 5. The ISI engages in a broad range of informing activities in support of the informing science transdiscipline. These include journal publications, organizing conferences, publishing books and offering services to members.

Journals

The ISI currently publishes eight journals. These are listed in Table 2. There are several common themes to these journals that have been established by the ISI. These include:

- Free open access to the online version of every article is available as soon as each article is accepted for final publication and appropriately formatted

- Articles are published under a Creative Commons license, allowing others to freely use their content (with proper attribution)

- Printed volumes are produced and made available for sale at the end of each year

- Double blind peer review is employed. Editors are required to make mentorship of authors a high priority throughout the review process, however.

| Title | Specialization/Mission | Authors through 2009 | Articles through 2009 | Institutions through 2009 | Year Founded |

| 1. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline | The flagship journal of the ISI, focusing on theory and practice of informing | 191 | 122 | 105 | 1998 |

| 2. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research | Serves the informational technology education audience on research-based issues | 407 | 205 | 196 | 2002 |

| 3. Journal of Information Technology Education: Innovations in Practice | Serves the informational technology education audience on issues in innovations in practice | 2008 | |||

| 4. Journal of Information Technology Education: Discussion Cases | Serves the informational technology education audience on the discussion case methods and practice | 2012 | |||

| 5.Interdisciplinary Journal of E-Skills and Lifelong Learning | Considers instructional technology issues of informing | 189 | 85 | 82 | 2005 |

| 6. Interdisciplinary Journal of Information, Knowledge, and Management | Considers information and technology in organizations | 78 | 37 | 43 | 2006 |

| 7. International Journal of Doctoral Studies | Considers issues with informing doctoral students | 34 | 19 | 20 | 2006 |

| 8. Journal of Information, Information Technology, and Organizations | Uses a balanced approach to information, technology, and organizational context | 58 | 32 | 31 | 2006 |

| 9. Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology Journal | Covers IT in all other disciplines | 542 | 392 | 226 | 2004 |

| 10. Journal of Information, Information Technology, and Organizations | Uses a balanced approach to information, technology, and organizational context | 58 | 32 | 31 | 2006 |

In 2016, the ISI family of journals was joined by a new ISI journal, Journal for the Study of Postsecondary and Tertiary Education. It also gained two "partner" journal, the Muma Case Review, and the Muma Business Review. Partner journals agree to abide by the ISI high standards for the treatment of authors and reviewers, but handle their own paper formatting and printing.

The ISI family of journals is also somewhat unusual for a U.S.-head quartered research publication in that its journals editorship and authorship is highly international in flavor. As shown in Figure 6, only about a third of its authors have been affiliated with U.S. academic institutions.

InSITE Conferences

One of the principal vehicles through which ISI informs its membership is through its Informing Science and IT Education conferences, held at a different location during June of every year since 2001. Attendance is typically around 150 participants. Conferences to date have been located as follows (Murphy, 2011, p. 117):

- InSITE 2016 - Vilnius, Lithuania

- InSITE 2015 - Tampa, Florida, USA

- InSITE 2014 - Wollongong, Australia

- InSITE 2013 - Porto, Portugal

- InSITE 2012 - Montreal, Canada

- InSITE 2011 - Novi Sad, Serbia

- InSITE 2010 - Cassino, Italy

- InSITE 2009 - Macon, Georgia, USA

- InSITE 2008 - Varna, Bulgaria

- InSITE 2007 - Ljubljana, Slovenia

- InSITE 2006 - Greater Manchester, England

- InSITE 2005 - Flagstaff, Arizona, USA

- InSITE 2004 - Rockhampton, Australia

- InSITE 2003 - Pori, Finland

- InSITE 2002 - Cork, Ireland

- InSITE 2001 - Kraków, Poland

Recent conferences have included four primary tracks (Murphy, 2011, p. 117-118):

- InSITE: Connect consists of study in various locations on the transmission of information across time and across space. Connect focuses on the interrelationship between context (his-torical forces and culture) and information and knowledge transfer.

- InSITE: Inform solicits papers in any area that explores issues in effectively and efficiently informing clients through information technology (IT).

- InSITE: TeachIT focuses on research topics related to teaching IT, including curricular is-sues, capstone courses, pedagogy, and emerging topics in IT.

- InSITE: TeLE focuses on research topics related to using IT to teach. For example, these topics include e-Learning, m-Learning, making classroom teaching more effective, and distance learning.

ISI has instituted a "fast track" process for article submissions to InSITE conferences. After all conference submissions have been reviewed, the editor-in-chiefs of ISI's seven journals identify articles that are of particularly high quality and are also a good fit with the journal's mission. Authors of these articles are then offered the opportunity to revise their submission for publication in the journal rather than in the conference proceedings.

Informing Science Press

The Informing Science Press is the publishing arm of the ISI. Its catalog of books—all available online for free on Google Books and for purchase—encompass a wide range of subjects. Topics that have been published up through 2009 are summarized in Table 3.

| Book Subject | Number |

| Education | 15 |

| e-learning | 13 |

| Informing Theory | 12 |

| Applied IS/IT | 11 |

| Knowledge Objects | 6 |

| Knowledge Management | 4 |

| Multimedia | 3 |

| Internationalization | 1 |

| Open-Source | 1 |

Future Directions

At the present time, the governing body of the Informing Science Institute is its Governors. These Governors traditionally meet in person during the InSITE conference and other times via phone conferencing. Among the plans recently discussed:

- The development of an Introduction to Informing Science textbook, to be published in 2012, that will offer a clearer picture of the transdiscipline and its objectives

- Future InSITE conferences are planned for Porto, Portugal (2013) and Wollongong, Australia (2014)

See also

References

- Bednar, P. and Welch, C. (2008). Bias, Misinformation and the Paradox of Neutrality. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline. 11, 85-106. Retrieved from http://www.inform.nu/Articles/Vol11/ISJv11p085-106Bednar528.pdf

- Bednar, P. and Welch, C. (2009). Inquiry into Informing Systems: Critical Systemic Thinking in Practice. In Gill, T.G. and Cohen, E.B. (Eds.)(2009). Foundations of Informing Science: 1999-2008, Santa Rosa, CA: Informing Science Press, 459-502.

- Callaos, N. and Callaos, B. (2002). Toward a Systemic Notion of Information: Practical Consequences. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline. 5(1), 1-11. Retrieved from http://www.inform.nu/Articles/Vol5/v5n1p001-011.pdf

- Christozov, D., Chukova, S. and Mateev, P. (2009). Informing Processes, Risks, Evaluation of the Risk of Misinforming. In Gill, T.G. and Cohen, E.B. (Eds.)(2009). Foundations of Informing Science: 1999-2008, Santa Rosa, CA: Informing Science Press, 323-356.

- Cohen, E.B. (1999). Reconceptualizing Information Systems as a Field of the Transdiscipline Informing Science: From Ugly Duckling to Swan, Journal of Computing and Information Technology, 7(3), 213-219, Retrieved from http://elicohen.info/uglyduckling.pdf

- Drucker, P. (1989). The New Realities. New York: Harper & Row.

- Fitzgerald, B. (2003). Informing Each Other: Bridging the Gap between Researcher and Practitioners. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline. 6, 13-19. Retrieved from http://www.inform.nu/Articles/Vol6/v6p013-019.pdf

- Gill, T.G. (2009a). Routine vs. Non-routine Informing: Reflections on What I Have Learned. In Gill, T.G. and Cohen, E.B. (Eds.)(2009). Foundations of Informing Science: 1999-2008, Santa Rosa, CA: Informing Science Press, 739-766.

- Gill, T.G. (2009b). An Open Letter to the Informing Science Community. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline. 12, v-x. Retrieved from http://inform.nu/Articles/Vol12/ISJv12pv-xGill.pdf

- Gill, T.G. (2010). Preface to Volume 13. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline. 13, v-vii. Retrieved from http://www.inform.nu/Articles/Vol13/ISJv13pv-viiGill.pdf

- Gill, T.G. (2011). When What is Useful is Not Necessarily True: The Underappreciated Conceptual Scheme. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline. 14, 1-32. Retrieved from http://www.inform.nu/Articles/Vol14/ISJv14p001-032Gill589.pdf

- Gill, T.G. and Bhattacherjee, A. (2007). The Informing Sciences at a Crossroads: The Role of the Client. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline. 10, 17-39. Retrieved from http://www.inform.nu/Articles/Vol10/ISJv10p017-039Gill317.pdf

- Gill, T.G. and Cohen, E.B. (2008). Research Themes in Complex Informing. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline. 11, 147-164. Retrieved from http://www.inform.nu/Articles/Vol11/ISJv11p147-164GillIntro.pdf

- Gill, T.G. and Cohen, E.B. (Eds.)(2009). Foundations of Informing Science: 1999-2008, Santa Rosa, CA: Informing Science Press.

- Gill, T.G. and Hicks, R.C. (2006). Task Complexity and Informing Science: A Synthesis. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline. 9, 1-30. Retrieved from http://www.inform.nu/Articles/Vol9/v9p001-030Gill46.pdf

- Hutchinson, W. (2006). Information Warfare and Deception. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline. 9, 213-223. Retrieved from http://www.inform.nu/Articles/Vol9/v9p213-223Hutchinson64.pdf

- Jamieson, K. and Hyland, P. (2006). Good Intuition or Fear and Uncertainty: The Effects of Bias on Information Systems Selection Decisions. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline. 9, 49-69. Retrieved from http://www.inform.nu/Articles/Vol9/v9p049-069Jamieson60.pdf

- Knox, K.T. (2009). Information and Informing Science. In Gill, T.G. and Cohen, E.B. (Eds.)(2009). Foundations of Informing Science: 1999-2008, Santa Rosa, CA: Informing Science Press, 135-158.

- Kuhn, T.S. (1970). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (2nd Edition, Enlarged). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Mende, J. (2005). The Poverty of Empiricism. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline. 8, 189-210. Retrieved from http://www.inform.nu/Articles/Vol8/v8p189-210Mende.pdf

- Murphy, W.F. (2011). The Informing Science Institute: The Informing System of a Transdiscipline. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline. 14, 91-123. Retrieved from http://www.inform.nu/Articles/Vol14/ISJv14p091-123Murphy598.pdf

- Myers, M.D., Baskerville, R.L., Gill, G. and Ramiller, N. (2011). Setting Our Research Agendas: Institutional Ecology, Informing Sciences, or Management Fashion Theory? Communications of the AIS, 28(1). 357-372. Retrieved from http://aisel.aisnet.org/cais/vol28/iss1/23/

- Nissen, H.E., Bednar, P. and Welch, C. (2007). Double Helix Relationships in Use and Design of Informing Systems: Lessons to Learn from Phenomenology and Hermeneutics. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline. 10, 1-19. Retrieved from http://www.inform.nu/Articles/Vol10/DblHelix001-019.pdf

- Pahl, .K. and Newnes, L.B. (2007). Co-evolution and Contradiction: A Diamond Model of Designer-User Interaction. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline. 10, 127-202. Retrieved from http://www.inform.nu/Articles/Vol10/DblHelix127-202.pdf

- Sarker, S. and Nicholson, J. (2005). Exploring the Myths about Online Education in Information Systems. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline. 8, 55-73. Retrieved from http://www.inform.nu/Articles/Vol8/v8p055-073Sarker.pdf

- Shannon, C.E. and Weaver, W. (1949). The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Sharda, N. (2005). Introduction to Special Series on Issues in Informing Clients using Multimedia Communications. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline. 8, 1. Retrieved from http://www.inform.nu/Articles/Vol8/v8p001-001Sharda.pdf

- Spasic, A. and Nesic, M. (2009). Informing Citizens in a Highly Restrictive Environment Using Low-Budget Multimedia Communications: A Serbian Case Study. In Gill, T.G. and Cohen, E.B. (Eds.)(2009). Foundations of Informing Science: 1999-2008, Santa Rosa, CA: Informing Science Press, 577-617.

- Spink, A. (2000). Informing Science Special Issue on Information Science Research. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline. 3(2), 47-48. Retrieved from http://www.inform.nu/Articles/Vol3/v3n2p47-48.pdf

- Travica, B. (2014). Examining the Informing View of Organization: Applying Theoretical and Managerial Approaches. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Travica, B. (2014). Think Process, Think in Time: Advancing Study of Informing Systems. Informing Science Journal, 17, 133-148. Retrieved from: http://www.inform.nu/Articles/Vol17/ISJv17p133-148Travica0519.pdf