Pray Codex

The Codex Pray, Pray Codex or The Hungarian Pray Manuscript is a collection of medieval manuscripts. In 1813 it was named after György Pray, who discovered it in 1770. It is the first known example of continuous prose text in Hungarian. The Codex is kept in the National Széchényi Library of Budapest.

One of the most prominent documents within the Codex (f. 154a) is the Funeral Sermon and Prayer (Hungarian: Halotti beszéd és könyörgés). It is an old handwritten Hungarian text dating to 1192-1195. Its importance of the Funeral Sermon comes from that it is the oldest surviving Hungarian, and Uralic, text.

The Codex also features a missal, an Easter mystery play, songs with musical notation, laws from the time of Coloman of Hungary and the annals, which list the Hungarian kings.

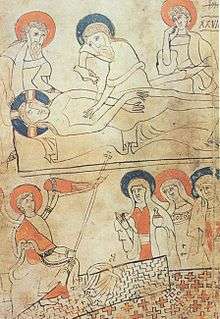

One of the five illustrations within the Codex shows the burial of Jesus. It is sometimes claimed that the display shows remarkable similarities with the Shroud of Turin: that Jesus is shown entirely naked with the arms on the pelvis, just like in the body image of the Shroud of Turin; that the thumbs on this image appear to be retracted, with only four fingers visible on each hand, thus matching detail on the Turin Shroud; that the supposed fabric shows a herringbone pattern, identical to the weaving pattern of the Shroud of Turin; and that the four tiny circles on the lower image, which appear to form a letter L, "perfectly reproduce four apparent "poker holes" on the Turin Shroud", which likewise appear to form a letter L.[1] The Codex Pray illustration may serve as evidence for the existence of the Shroud of Turin prior to 1260–1390 AD, the fabrication date established in the radiocarbon 14 dating of the Shroud of Turin in 1988.[2] Critics of this idea point out, that the item that is sometimes identified as the Shroud is probably a rectangular tombstone as seen on other sacred images. The alleged holes may just be decorative elements, as seen, for example, on the angel's wing. Moreover, the alleged shroud in the Pray codex does not contain any image.[3]

References

- ↑ Daniel C. Scavone. "Book Review of "The Turin Shroud: In Whose Image?"". Shroud.com. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ↑ E. Poulle, "Les sources de l'histoire du linceul de Turin, Revue Critique", Revue d'histoire ecclésiastique, 104, 3-4, 2009, pp. 772-773.

- ↑ G.M.Rinaldi, "Il Codice Pray", http://sindone.weebly.com/pray.html

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pray Codex. |