Human–computer interaction

Human–computer interaction (HCI) researches the design and use of computer technology, focused on the interfaces between people (users) and computers. Researchers in the field of HCI both observe the ways in which humans interact with computers and design technologies that let humans interact with computers in novel ways. As a field of research, human–computer interaction is situated at the intersection of computer science, behavioral sciences, design, media studies, and several other fields of study. The term was popularized by Stuart K. Card, Allen Newell, and Thomas P. Moran in their seminal 1983 book, The Psychology of Human–Computer Interaction, although the authors first used the term in 1980[1] and the first known use was in 1975.[2] The term connotes that, unlike other tools with only limited uses (such as a hammer, useful for driving nails but not much else), a computer has many uses and this takes place as an open-ended dialog between the user and the computer. The notion of dialog likens human–computer interaction to human-to-human interaction, an analogy which is crucial to theoretical considerations in the field.[3][4]

Introduction

Humans interact with computers in many ways; the interface between humans and computers is crucial to facilitating this interaction. Desktop applications, internet browsers, handheld computers, and computer kiosks make use of the prevalent graphical user interfaces (GUI) of today.[5] Voice user interfaces (VUI) are used for speech recognition and synthesising systems, and the emerging multi-modal and Graphical user interfaces (GUI) allow humans to engage with embodied character agents in a way that cannot be achieved with other interface paradigms. The growth in human–computer interaction field has been in quality of interaction, and in different branching in its history. Instead of designing regular interfaces, the different research branches have had a different focus on the concepts of multimodality rather than unimodality, intelligent adaptive interfaces rather than command/action based ones, and finally active rather than passive interfaces.

The Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) defines human–computer interaction as "a discipline concerned with the design, evaluation and implementation of interactive computing systems for human use and with the study of major phenomena surrounding them".[5] An important facet of HCI is user satisfaction (or simply End User Computing Satisfaction). "Because human–computer interaction studies a human and a machine in communication, it draws from supporting knowledge on both the machine and the human side. On the machine side, techniques in computer graphics, operating systems, programming languages, and development environments are relevant. On the human side, communication theory, graphic and industrial design disciplines, linguistics, social sciences, cognitive psychology, social psychology, and human factors such as computer user satisfaction are relevant. And, of course, engineering and design methods are relevant."[5] Due to the multidisciplinary nature of HCI, people with different backgrounds contribute to its success. HCI is also sometimes termed human–machine interaction (HMI), man-machine interaction (MMI) or computer-human interaction (CHI).

Poorly designed human-machine interfaces can lead to many unexpected problems. A classic example is the Three Mile Island accident, a nuclear meltdown accident, where investigations concluded that the design of the human-machine interface was at least partly responsible for the disaster.[6][7][8] Similarly, accidents in aviation have resulted from manufacturers' decisions to use non-standard flight instrument or throttle quadrant layouts: even though the new designs were proposed to be superior in basic human-machine interaction, pilots had already ingrained the "standard" layout and thus the conceptually good idea actually had undesirable results.

Goals for computers

Human–computer interaction studies the ways in which humans make, or do not make, use of computational artifacts, systems and infrastructures. In doing so, much of the research in the field seeks to improve human–computer interaction by improving the usability of computer interfaces.[9] How usability is to be precisely understood, how it relates to other social and cultural values and when it is, and when it may not be a desirable property of computer interfaces is increasingly debated.[10][11]

Much of the research in the field of human–computer interaction takes an interest in:

- Methods for designing new computer interfaces, thereby optimizing a design for a desired property such as learnability or efficiency of use.

- Methods for implementing interfaces, e.g., by means of software libraries.

- Methods for evaluating and comparing interfaces with respect to their usability and other desirable properties.

- Methods for studying human computer use and its sociocultural implications more broadly.

- Models and theories of human computer use as well as conceptual frameworks for the design of computer interfaces, such as cognitivist user models, Activity Theory or ethnomethodological accounts of human computer use.[12]

- Perspectives that critically reflect upon the values that underlie computational design, computer use and HCI research practice.[13]

Visions of what researchers in the field seek to achieve vary. When pursuing a cognitivist perspective, researchers of HCI may seek to align computer interfaces with the mental model that humans have of their activities. When pursuing a post-cognitivist perspective, researchers of HCI may seek to align computer interfaces with existing social practices or existing sociocultural values.

Researchers in HCI are interested in developing design methodologies, experimenting with devices, prototyping software and hardware systems, exploring interaction paradigms, and developing models and theories of interaction.

Differences with related fields

HCI differs from human factors and ergonomics as HCI focuses more on users working specifically with computers, rather than other kinds of machines or designed artifacts. There is also a focus in HCI on how to implement the computer software and hardware mechanisms to support human–computer interaction. Thus, human factors is a broader term; HCI could be described as the human factors of computers – although some experts try to differentiate these areas.

HCI also differs from human factors in that there is less of a focus on repetitive work-oriented tasks and procedures, and much less emphasis on physical stress and the physical form or industrial design of the user interface, such as keyboards and mouse devices.

Three areas of study have substantial overlap with HCI even as the focus of inquiry shifts. Personal information management (PIM) studies how people acquire and use personal information (computer based and other) to complete tasks. In computer-supported cooperative work (CSCW), emphasis is placed on the use of computing systems in support of the collaborative work. The principles of human interaction management (HIM) extend the scope of CSCW to an organizational level and can be implemented without use of computers.

Design

Principles

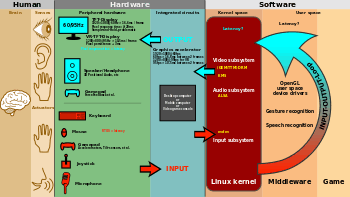

Software and hardware must be matched, so that the processing of the user input is fast enough, the latency of the computer output is not disruptive to the workflow.

When evaluating a current user interface, or designing a new user interface, it is important to keep in mind the following experimental design principles:

- Early focus on user(s) and task(s): Establish how many users are needed to perform the task(s) and determine who the appropriate users should be; someone who has never used the interface, and will not use the interface in the future, is most likely not a valid user. In addition, define the task(s) the users will be performing and how often the task(s) need to be performed.

- Empirical measurement: Test the interface early on with real users who come in contact with the interface on a daily basis. Keep in mind that results may vary with the performance level of the user and may not accurately depict the typical human–computer interaction. Establish quantitative usability specifics such as: the number of users performing the task(s), the time to complete the task(s), and the number of errors made during the task(s).

- Iterative design: After determining the users, tasks, and empirical measurements to include, perform the following iterative design steps:

- Design the user interface

- Test

- Analyze results

- Repeat

Repeat the iterative design process until a sensible, user-friendly interface is created.[14]

Methodologies

A number of diverse methodologies outlining techniques for human–computer interaction design have emerged since the rise of the field in the 1980s. Most design methodologies stem from a model for how users, designers, and technical systems interact. Early methodologies, for example, treated users' cognitive processes as predictable and quantifiable and encouraged design practitioners to look to cognitive science results in areas such as memory and attention when designing user interfaces. Modern models tend to focus on a constant feedback and conversation between users, designers, and engineers and push for technical systems to be wrapped around the types of experiences users want to have, rather than wrapping user experience around a completed system.

- Activity theory: used in HCI to define and study the context in which human interactions with computers take place. Activity theory provides a framework to reason about actions in these contexts, analytical tools with the format of checklists of items that researchers should consider, and informs design of interactions from an activity-centric perspective.[15]

- User-centered design: user-centered design (UCD) is a modern, widely practiced design philosophy rooted in the idea that users must take center-stage in the design of any computer system. Users, designers and technical practitioners work together to articulate the needs and limitations of the user and create a system that addresses these elements. Often, user-centered design projects are informed by ethnographic studies of the environments in which users will be interacting with the system. This practice is similar to participatory design, which emphasizes the possibility for end-users to contribute actively through shared design sessions and workshops.

- Principles of user interface design: these principles may be considered at any time during the design of a user interface in any order: tolerance, simplicity, visibility, affordance, consistency, structure and feedback.[16]

- Value sensitive design (VSD): a method for building technology that account for the values of the people who use the technology directly, as well as those who the technology affects, either directly or indirectly. VSD uses an iterative design process that involves three types of investigations: conceptual, empirical and technical. Conceptual investigations aim at understanding and articulating the various stakeholders of the technology, as well as their values and any values conflicts that might arise for these stakeholders through the use of the technology. Empirical investigations are qualitative or quantitative design research studies used to inform the designers' understanding of the users' values, needs, and practices. Technical investigations can involve either analysis of how people use related technologies, or the design of systems to support values identified in the conceptual and empirical investigations.[17]

Display designs

Displays are human-made artifacts designed to support the perception of relevant system variables and to facilitate further processing of that information. Before a display is designed, the task that the display is intended to support must be defined (e.g. navigating, controlling, decision making, learning, entertaining, etc.). A user or operator must be able to process whatever information that a system generates and displays; therefore, the information must be displayed according to principles in a manner that will support perception, situation awareness, and understanding.

Thirteen principles of display design

Christopher Wickens et al. defined 13 principles of display design in their book An Introduction to Human Factors Engineering.[18]

These principles of human perception and information processing can be utilized to create an effective display design. A reduction in errors, a reduction in required training time, an increase in efficiency, and an increase in user satisfaction are a few of the many potential benefits that can be achieved through utilization of these principles.

Certain principles may not be applicable to different displays or situations. Some principles may seem to be conflicting, and there is no simple solution to say that one principle is more important than another. The principles may be tailored to a specific design or situation. Striking a functional balance among the principles is critical for an effective design.[19]

Perceptual principles

1. Make displays legible (or audible). A display's legibility is critical and necessary for designing a usable display. If the characters or objects being displayed cannot be discernible, then the operator cannot effectively make use of them.

2. Avoid absolute judgment limits. Do not ask the user to determine the level of a variable on the basis of a single sensory variable (e.g. colour, size, loudness). These sensory variables can contain many possible levels.

3. Top-down processing. Signals are likely perceived and interpreted in accordance with what is expected based on a user's experience. If a signal is presented contrary to the user's expectation, more physical evidence of that signal may need to be presented to assure that it is understood correctly.

4. Redundancy gain. If a signal is presented more than once, it is more likely that it will be understood correctly. This can be done by presenting the signal in alternative physical forms (e.g. colour and shape, voice and print, etc.), as redundancy does not imply repetition. A traffic light is a good example of redundancy, as colour and position are redundant.

5. Similarity causes confusion: Use distinguishable elements. Signals that appear to be similar will likely be confused. The ratio of similar features to different features causes signals to be similar. For example, A423B9 is more similar to A423B8 than 92 is to 93. Unnecessarily similar features should be removed and dissimilar features should be highlighted.

Mental model principles

6. Principle of pictorial realism. A display should look like the variable that it represents (e.g. high temperature on a thermometer shown as a higher vertical level). If there are multiple elements, they can be configured in a manner that looks like it would in the represented environment.

7. Principle of the moving part. Moving elements should move in a pattern and direction compatible with the user's mental model of how it actually moves in the system. For example, the moving element on an altimeter should move upward with increasing altitude.

Principles based on attention

8. Minimizing information access cost or interaction cost. When the user's attention is diverted from one location to another to access necessary information, there is an associated cost in time or effort. A display design should minimize this cost by allowing for frequently accessed sources to be located at the nearest possible position. However, adequate legibility should not be sacrificed to reduce this cost.

9. Proximity compatibility principle. Divided attention between two information sources may be necessary for the completion of one task. These sources must be mentally integrated and are defined to have close mental proximity. Information access costs should be low, which can be achieved in many ways (e.g. proximity, linkage by common colours, patterns, shapes, etc.). However, close display proximity can be harmful by causing too much clutter.

10. Principle of multiple resources. A user can more easily process information across different resources. For example, visual and auditory information can be presented simultaneously rather than presenting all visual or all auditory information.

Memory principles

11. Replace memory with visual information: knowledge in the world. A user should not need to retain important information solely in working memory or retrieve it from long-term memory. A menu, checklist, or another display can aid the user by easing the use of their memory. However, the use of memory may sometimes benefit the user by eliminating the need to reference some type of knowledge in the world (e.g., an expert computer operator would rather use direct commands from memory than refer to a manual). The use of knowledge in a user's head and knowledge in the world must be balanced for an effective design.

12. Principle of predictive aiding. Proactive actions are usually more effective than reactive actions. A display should attempt to eliminate resource-demanding cognitive tasks and replace them with simpler perceptual tasks to reduce the use of the user's mental resources. This will allow the user to focus on current conditions, and to consider possible future conditions. An example of a predictive aid is a road sign displaying the distance to a certain destination.

13. Principle of consistency. Old habits from other displays will easily transfer to support processing of new displays if they are designed consistently. A user's long-term memory will trigger actions that are expected to be appropriate. A design must accept this fact and utilize consistency among different displays.

Human–computer interface

The human–computer interface can be described as the point of communication between the human user and the computer. The flow of information between the human and computer is defined as the loop of interaction. The loop of interaction has several aspects to it, including:

- Visual Based :The visual based human computer inter-action is probably the most widespread area in Human Computer Interaction (HCI) research.

- Audio Based : The audio based interaction between a computer and a human is another important area of in HCI systems. This area deals with information acquired by different audio signals.

- Task environment: The conditions and goals set upon the user.

- Machine environment: The environment that the computer is connected to, e.g. a laptop in a college student's dorm room.

- Areas of the interface: Non-overlapping areas involve processes of the human and computer not pertaining to their interaction. Meanwhile, the overlapping areas only concern themselves with the processes pertaining to their interaction.

- Input flow: The flow of information that begins in the task environment, when the user has some task that requires using their computer.

- Output: The flow of information that originates in the machine environment.

- Feedback: Loops through the interface that evaluate, moderate, and confirm processes as they pass from the human through the interface to the computer and back.

- Fit: This is the match between the computer design, the user and the task to optimize the human resources needed to accomplish the task.

Current research

Topics in human-computer interaction include:

User customization

End-user development studies how ordinary users could routinely tailor applications to their own needs and to invent new applications based on their understanding of their own domains. With their deeper knowledge, users could increasingly be important sources of new applications at the expense of generic programmers with systems expertise but low domain expertise.

Embedded computation

Computation is passing beyond computers into every object for which uses can be found. Embedded systems make the environment alive with little computations and automated processes, from computerized cooking appliances to lighting and plumbing fixtures to window blinds to automobile braking systems to greeting cards. The expected difference in the future is the addition of networked communications that will allow many of these embedded computations to coordinate with each other and with the user. Human interfaces to these embedded devices will in many cases be disparate from those appropriate to workstations.

Augmented reality

Augmented reality refers to the notion of layering relevant information into our vision of the world. Existing projects show real-time statistics to users performing difficult tasks, such as manufacturing. Future work might include augmenting our social interactions by providing additional information about those we converse with.

Social computing

In recent years, there has been an explosion of social science research focusing on interactions as the unit of analysis. Much of this research draws from psychology, social psychology, and sociology. For example, one study found out that people expected a computer with a man's name to cost more than a machine with a woman's name.[20] Other research finds that individuals perceive their interactions with computers more positively than humans, despite behaving the same way towards these machines.[21]

Knowledge-driven human–computer interaction

In human and computer interactions, a semantic gap usually exists between human and computer's understandings towards mutual behaviors. Ontology (information science), as a formal representation of domain-specific knowledge, can be used to address this problem, through solving the semantic ambiguities between the two parties.[22]

Emotions and human-computer interaction

In the interaction of humans and computers, research has studied how computers can detect, process and react to human emotions to develop emotionally intelligent information systems. Researchers have suggested several 'affect-detection channels'.[23] The potential of telling human emotions in an automated and digital fashion lies in improvements to the effectiveness of human-computer interaction.[24] The influence of emotions in human-computer interaction has been studied in fields such as financial decision making using ECG[25][26] and organisational knowledge sharing using eye tracking and face readers as affect-detection channels.[27] In these fields it has been shown that affect-detection channels have the potential to detect human emotions and that information systems can incorporate the data obtained from affect-detection channels to improve decision models.

Brain–computer interfaces

Factors of change

Traditionally, computer use was modeled as a human–computer dyad in which the two were connected by a narrow explicit communication channel, such as text-based terminals. Much work has been done to make the interaction between a computing system and a human more reflective of the multidimensional nature of everyday communication. Because of potential issues, human–computer interaction shifted focus beyond the interface to respond to observations as articulated by D. Engelbart: "If ease of use was the only valid criterion, people would stick to tricycles and never try bicycles."[28]

The means by which humans interact with computers continues to evolve rapidly. Human–computer interaction is affected by developments in computing. These forces include:

- Decreasing hardware costs leading to larger memory and faster systems

- Miniaturization of hardware leading to portability

- Reduction in power requirements leading to portability

- New display technologies leading to the packaging of computational devices in new forms

- Specialized hardware leading to new functions

- Increased development of network communication and distributed computing

- Increasingly widespread use of computers, especially by people who are outside of the computing profession

- Increasing innovation in input techniques (e.g., voice, gesture, pen), combined with lowering cost, leading to rapid computerization by people formerly left out of the computer revolution.

- Wider social concerns leading to improved access to computers by currently disadvantaged groups

As of 2010 the future for HCI is expected[29] to include the following characteristics:

- Ubiquitous computing and communication. Computers are expected to communicate through high speed local networks, nationally over wide-area networks, and portably via infrared, ultrasonic, cellular, and other technologies. Data and computational services will be portably accessible from many if not most locations to which a user travels.

- High-functionality systems. Systems can have large numbers of functions associated with them. There are so many systems that most users, technical or non-technical, do not have time to learn them in the traditional way (e.g., through thick manuals).

- Mass availability of computer graphics. Computer graphics capabilities such as image processing, graphics transformations, rendering, and interactive animation are becoming widespread as inexpensive chips become available for inclusion in general workstations and mobile devices.

- Mixed media. Commercial systems can handle images, voice, sounds, video, text, formatted data. These are exchangeable over communication links among users. The separate fields of consumer electronics (e.g., stereo sets, VCRs, televisions) and computers are merging partly. Computer and print fields are expected to cross-assimilate.

- High-bandwidth interaction. The rate at which humans and machines interact is expected to increase substantially due to the changes in speed, computer graphics, new media, and new input/output devices. This can lead to some qualitatively different interfaces, such as virtual reality or computational video.

- Large and thin displays. New display technologies are maturing, enabling very large displays and displays that are thin, lightweight, and low in power use. This is having large effects on portability and will likely enable developing paper-like, pen-based computer interaction systems very different in feel from present desktop workstations.

- Information utilities. Public information utilities (such as home banking and shopping) and specialized industry services (e.g., weather for pilots) are expected to proliferate. The rate of proliferation can accelerate with the introduction of high-bandwidth interaction and the improvement in quality of interfaces.

Scientific conferences

One of the main conferences for new research in human–computer interaction is the annually held Association for Computing Machinery's (ACM) Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, usually referred to by its short name CHI (pronounced kai, or khai). CHI is organized by ACM Special Interest Group on Computer–Human Interaction (SIGCHI). CHI is a large conference, with thousands of attendants, and is quite broad in scope. It is attended by academics, practitioners and industry people, with company sponsors such as Google, Microsoft, and PayPal.

There are also dozens of other smaller, regional or specialized HCI-related conferences held around the world each year, including:[30]

- ASSETS: ACM International Conference on Computers and Accessibility

- CSCW: ACM conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work

- CC: Aarhus decennial conference on Critical Computing

- DIS: ACM conference on Designing Interactive Systems

- ECSCW: European Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work

- GROUP: ACM conference on supporting group work

- HRI: ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human–robot interaction

- HCII: Human–Computer Interaction International

- ICMI: International Conference on Multimodal Interfaces

- ITS: ACM conference on Interactive Tabletops and Surfaces

- MobileHCI: International Conference on Human–Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services

- NIME: International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression

- OzCHI: Australian Conference on Human–Computer Interaction

- TEI: International Conference on Tangible, Embedded and Embodied Interaction

- Ubicomp: International Conference on Ubiquitous computing

- UIST: ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology

- i-USEr: International Conference on User Science and Engineering

- INTERACT: IFIP TC13 Conference on Human–Computer Interaction

See also

- Outline of human–computer interaction

- Information design

- Experience design

- Information architecture

- Physiological interaction

- User experience design

- Mindfulness and technology

- HCI Bibliography, a web-based project to provide a bibliography of Human Computer Interaction literature

Footnotes

- ↑ Card, Stuart K.; Thomas P. Moran; Allen Newell (July 1980). "The keystroke-level model for user performance time with interactive systems". Communications of the ACM. 23 (7): 396–410. doi:10.1145/358886.358895.

- ↑ Carlisle, James H. (June 1976). "Evaluating the impact of office automation on top management communication". Proceedings of the June 7-10, 1976, national computer conference and exposition on - AFIPS '76. Proceedings of the June 7–10, 1976, National Computer Conference and Exposition. pp. 611–616. doi:10.1145/1499799.1499885.

Use of 'human–computer interaction' appears in references

- ↑ Suchman, Lucy (1987). Plans and Situated Action. The Problem of Human–Machine Communication. New York, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521337397. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ↑ Dourish, Paul (2001). Where the Action Is: The Foundations of Embodied Interaction. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262541787.

- 1 2 3 Hewett; Baecker; Card; Carey; Gasen; Mantei; Perlman; Strong; Verplank. "ACM SIGCHI Curricula for Human–Computer Interaction". ACM SIGCHI. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ↑ Ergoweb. "What is Cognitive Ergonomics?". Ergoweb.com. Retrieved August 29, 2011.

- ↑ "NRC: Backgrounder on the Three Mile Island Accident". Nrc.gov. Retrieved August 29, 2011.

- ↑ http://www.threemileisland.org/downloads/188.pdf

- ↑ Grudin, Jonathan (1992). "Utility and usability: research issues and development contexts". Interacting with Computers. 4 (2): 209–217. doi:10.1016/0953-5438(92)90005-z. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ↑ Chalmers, Matthew; Galani, Areti (2004). Seamful interweaving: heterogeneity in the theory and design of interactive systems. Procee ' ]p[p Plluuykk ] [jioopji[dings of the 5th Conference on Designing Interactive Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, and Techniques. pp. 243–252. doi:10.1145/1013115.1013149. ISBN 978-1581137873. Retrieved 7 March 2015. line feed character in

|journal=at position 7 (help) - ↑ Barkhuus, Louise; Polichar, Valerie E. (2011). "Empowerment through seamfulness: smart phones in everyday life". Personal and Ubiquitous Computing. 15 (6): 629–639. doi:10.1007/s00779-010-0342-4.

- ↑ Rogers, Yvonne (2012). "HCI Theory: Classical, Modern, and Contemporary". Synthesis Lectures on Human-Centered Informatics. 5 (2): 1–129. doi:10.2200/S00418ED1V01Y201205HCI014.

- ↑ Sengers, Phoebe; Boehner, Kirsten; David, Shay; Joseph, Kaye (2005). Reflective Design. CC '05 Proceedings of the 4th Decennial Conference on Critical Computing: Between Sense and Sensibility. 5. pp. 49–58. doi:10.1145/1094562.1094569. ISBN 978-1595932037. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ↑ Green, Paul (2008). Iterative Design. Lecture presented in Industrial and Operations Engineering 436 (Human Factors in Computer Systems, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, February 4, 2008.

- ↑ Kaptelinin, Victor (2012): Activity Theory. In: Soegaard, Mads and Dam, Rikke Friis (eds.). "Encyclopedia of Human–Computer Interaction". The Interaction-Design.org Foundation. Available online at http://www.interaction-design.org/encyclopedia/activity_theory.html

- ↑ "The Case for HCI Design Patterns".

- ↑ Friedman, B., Kahn Jr, P. H., Borning, A., & Kahn, P. H. (2006). Value Sensitive Design and information systems. Human–Computer Interaction and Management Information Systems: Foundations. ME Sharpe, New York, 348–372.

- ↑ Wickens, Christopher D., John D. Lee, Yili Liu, and Sallie E. Gordon Becker. An Introduction to Human Factors Engineering. Second ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2004. 185–193.

- ↑ Brown, C. Marlin. Human–Computer Interface Design Guidelines. Intellect Books, 1998. 2–3.

- ↑ Posard, Marek (2014). "Status processes in human–computer interactions: Does gender matter?". Computers in Human Behavior. 37 (37): 189–195. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.025.

- ↑ Posard, Marek; Rinderknecht, R. Gordon (2015). "Do people like working with computers more than human beings?". Computers in Human Behavior. 51: 232–238. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.057.

- ↑ Dong, Hai; Hussain, Farookh; Elizabeth, Chang. "A human-centered semantic service platform for the digital ecosystems environment". World Wide Web. 13 (1–2): 75–103.

- ↑ Calvo, R., & D'Mello S. (2010). "Affect detection: An interdisciplinary review of models, methods, and their applications". IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing. 1 (1).

- ↑ Cowie, R., Douglas-Cowie, E., Tsapatsoulis, N., Votsis, G., Kollias, S., Fellenz, W., & Taylor, J. G. (2001). "Emotion recognition in human-computer interaction". IEEE Signal Processing Magazine. 18 (1).

- ↑ Astor, Philipp J.; Adam, Marc T. P.; Jerčić, Petar; Schaaff, Kristina; Weinhardt, Christof (2013-12). "Integrating Biosignals into Information Systems: A NeuroIS Tool for Improving Emotion Regulation". Journal of Management Information Systems. 30 (3): 247–278. doi:10.2753/mis0742-1222300309. ISSN 0742-1222. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Adam, Marc T. P.; Krämer, Jan; Weinhardt, Christof (2012-12). "Excitement Up! Price Down! Measuring Emotions in Dutch Auctions". International Journal of Electronic Commerce. 17 (2): 7–40. doi:10.2753/jec1086-4415170201. ISSN 1086-4415. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ D, Fehrenbacher, Dennis (2017). "Affect Infusion and Detection through Faces in Computer-mediated Knowledge-sharing Decisions". Journal of the Association for Information Systems. 18 (10). ISSN 1536-9323.

- ↑ Fischer, Gerhard (1 May 2000). "User Modeling in Human–Computer Interaction". User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction. 11 (1–2): 65–86. doi:10.1023/A:1011145532042.

- ↑ SINHA, Gaurav; SHAHI, Rahul; SHANKAR, Mani. Human Computer Interaction. In: Emerging Trends in Engineering and Technology (ICETET), 2010 3rd International Conference on. IEEE, 2010. p. 1-4.

- ↑ "Conference Search: hci". www.confsearch.org.

Further reading

- Academic overviews of the field

- Julie A. Jacko (Ed.). (2012). Human–Computer Interaction Handbook (3rd Edition). CRC Press. ISBN 1-4398-2943-8

- Andrew Sears and Julie A. Jacko (Eds.). (2007). Human–Computer Interaction Handbook (2nd Edition). CRC Press. ISBN 0-8058-5870-9

- Julie A. Jacko and Andrew Sears (Eds.). (2003). Human–Computer Interaction Handbook. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum & Associates. ISBN 0-8058-4468-6

- Historically important classic

- Stuart K. Card, Thomas P. Moran, Allen Newell (1983): The Psychology of Human–Computer Interaction. Erlbaum, Hillsdale 1983 ISBN 0-89859-243-7

- Overviews of history of the field

- Jonathan Grudin: A moving target: The evolution of human–computer interaction. In Andrew Sears and Julie A. Jacko (Eds.). (2007). Human–Computer Interaction Handbook (2nd Edition). CRC Press. ISBN 0-8058-5870-9

- Myers, Brad (1998). "A brief history of human–computer interaction technology". Interactions. 5 (2): 44–54. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.23.2422. doi:10.1145/274430.274436.

- John M. Carroll: Human Computer Interaction: History and Status. Encyclopedia Entry at Interaction-Design.org

- Carroll, John M. (2010). "Conceptualizing a possible discipline of human–computer interaction". Interacting with Computers. 22 (1): 3–12. doi:10.1016/j.intcom.2009.11.008.

- Sara Candeias, S. and A. Veiga The dialogue between man and machine: the role of language theory and technology, Sandra M. Aluísio & Stella E. O. Tagnin, New Language Technologies and Linguistic Research, A Two-Way Road: cap. 11. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ( ISBN 978-1-4438-5377-4)

- Social science and HCI

- Nass, Clifford; Fogg, B. J.; Moon, Youngme (1996). "Can computers be teammates?". International Journal of Human–Computer Studies. 45 (6): 669–678. doi:10.1006/ijhc.1996.0073.

- Nass, Clifford; Moon, Youngme (2000). "Machines and mindlessness: Social responses to computers". Journal of Social Issues. 56 (1): 81–103. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00153.

- Posard, Marek N (2014). "Status processes in human–computer interactions: Does gender matter?". Computers in Human Behavior. 37: 189–195. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.025.

- Posard, Marek N.; Rinderknecht, R. Gordon (2015). "Do people like working with computers more than human beings?". Computers in Human Behavior. 51: 232–238. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.057.

- Academic journals

- ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction

- Behaviour & Information Technology

- Interacting with Computers

- International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction

- International Journal of Human–Computer Studies

- Human–Computer Interaction

- Collection of papers

- Ronald M. Baecker, Jonathan Grudin, William A. S. Buxton, Saul Greenberg (Eds.) (1995): Readings in human–computer interaction. Toward the Year 2000. 2. ed. Morgan Kaufmann, San Francisco 1995 ISBN 1-55860-246-1

- Mithun Ahamed, Developing a Message Interface Architecture for Android Operating Systems, (2015).

- Treatments by one or few authors, often aimed at a more general audience

- Jakob Nielsen: Usability Engineering. Academic Press, Boston 1993 ISBN 0-12-518405-0

- Donald A. Norman: The Psychology of Everyday Things. Basic Books, New York 1988 ISBN 0-465-06709-3

- Jef Raskin: The Humane Interface. New directions for designing interactive systems. Addison-Wesley, Boston 2000 ISBN 0-201-37937-6

- Bruce Tognazzini: Tog on Interface. Addison-Wesley, Reading 1991 ISBN 0-201-60842-1

- Textbooks

- Alan Dix, Janet Finlay, Gregory Abowd, and Russell Beale (2003): Human–Computer Interaction. 3rd Edition. Prentice Hall, 2003. http://hcibook.com/e3/ ISBN 0-13-046109-1

- Yvonne Rogers, Helen Sharp & Jenny Preece: Interaction Design: Beyond Human–Computer Interaction, 3rd ed. John Wiley & Sons Ltd., 2011 ISBN 0-470-66576-9

- Helen Sharp, Yvonne Rogers & Jenny Preece: Interaction Design: Beyond Human–Computer Interaction, 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons Ltd., 2007 ISBN 0-470-01866-6

- Matt Jones (interaction designer) and Gary Marsden (2006). Mobile Interaction Design, John Wiley and Sons Ltd.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Human–computer interaction. |

- Bad Human Factors Designs

- The HCI Wiki Bibliography with over 100,000 publications.

- The HCI Bibliography Over 100,000 publications about HCI.

- Human–Centered Computing Education Digital Library

- HCI Webliography