History of journalism

| Journalism |

|---|

|

| Areas |

| Genres |

| Social impact |

| News media |

| Roles |

|

The history of journalism, or the development of the gathering and transmitting of news spans the growth of technology and trade, marked by the advent of specialized techniques for gathering and disseminating information on a regular basis that has caused, as one history of journalism surmises, the steady increase of "the scope of news available to us and the speed with which it is transmitted. Before the printing press was invented, word of mouth was the primary source of news. Returning merchants, sailors and travelers brought news back to the mainland, and this was then picked up by pedlars and travelling players and spread from town to town. Ancient scribes often wrote this information down. This transmission of news was highly unreliable, and died out with the invention of the printing press. Newspapers (and to a lesser extent magazines) have always been the primary medium of journalists since the 18th century, radio and television in the 20th century, and the Internet in the 21st century.[1]

Early and Basic journalism

Europe

In 1556, the government of Venice first published the monthly Notizie scritte ("Written notices") which cost one gazetta,[2] a Venetian coin of the time, the name of which eventually came to mean "newspaper". These avvisi were handwritten newsletters and used to convey political, military, and economic news quickly and efficiently throughout Europe, more specifically Italy, during the early modern era (1500-1800)—sharing some characteristics of newspapers though usually not considered true newspapers.[3]

However, none of these publications fully met the modern criteria for proper newspapers, as they were typically not intended for the general public and restricted to a certain range of topics.

Early publications played into the development of what would today be recognized as the newspaper, which came about around 1601. Around the 15th and 16th centuries, in England and France, long news accounts called "relations" were published; in Spain they were called "relaciones".

Single event news publications were printed in the broadsheet format, which was often posted. These publications also appeared as pamphlets and small booklets (for longer narratives, often written in a letter format), often containing woodcut illustrations. Literacy rates were low in comparison to today, and these news publications were often read aloud (literacy and oral culture were, in a sense, existing side by side in this scenario).

By 1400, businessmen in Italian and German cities were compiling hand written chronicles of important news events, and circulating them to their business connections. The idea of using a printing press for this material first appeared in Germany around 1600. The first gazettes appeared in German cities, notably the weekly Relation aller Fuernemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien ("Collection of all distinguished and memorable news") in Strasbourg starting in 1605. The Avisa Relation oder Zeitung was published in Wolfenbüttel from 1609, and gazettes soon were established in Frankfurt (1615), Berlin (1617) and Hamburg (1618). By 1650, 30 German cities had active gazettes.[4] A semi-yearly news chronicle, in Latin, the Mercurius Gallobelgicus, was published at Cologne between 1594 and 1635, but it was not the model for other publications.

The news circulated between newsletters through well-established channels in 17th century Europe. Antwerp was the hub of two networks, one linking France, Britain, Germany, and the Netherlands; the other linking Italy Spain and Portugal. Favorite topics included wars, military affairs, diplomacy, and court business and gossip.[5]

After 1600 the national governments in France and England began printing official newsletters.[6] In 1622 the first English-language weekly magazine, "A current of General News" was published and distributed in England[7] in an 8- to 24-page quarto format.

Revolutionary changes in the 19th century

Newspapers in all major countries became much more important in the 19th century because of a series of technical, business, political, and cultural changes. High-speed presses and cheap wood-based newsprint made large circulations possible. The rapid expansion of elementary education meant a vast increase in the number of potential readers. Political parties sponsored newspapers at the local and national level. Toward the end of the century, advertising became well-established and became the main source of revenue for newspaper owners. This led to a race to obtain the largest possible circulation, often followed by downplaying partisanship so that members of all parties would buy a paper. The number of newspapers in Europe the 1860s and 1870s was steady at about 6,000; then it doubled to 12,000 in 1900. In the 1860s and 1870s, most newspapers were four pages of editorials, reprinted speeches, excerpts from novels and poetry and a few small local ads. They were expensive, and most readers went to a café to look over the latest issue. There were major national papers in each capital city, such as the London Times, the London Post, the Paris Temps and so on. They were expensive and directed to the National political elite. Every decade the presses became faster, and the invention of automatic typesetting in the 1880s made feasible the overnight printing of a large morning newspaper. Cheap wood pulp replaced became the much expensive rag paper. A major cultural innovation, was the professionalization of news gathering, handled by specialist reporters. Liberalism led to freedom of the press, and ended newspaper taxes, along with a sharp reduction to government censorship. Entrepreneurs interested in profit increasingly replaced politicians interested in shaping party positions, so there was dramatic outreach to a larger subscription base. The price fell to a penny. In New York, "Yellow Journalism" used sensationalism, comics (they were colored yellow), a strong emphasis on team sports, reduced coverage of political details and speeches, a new emphasis on crime, and a vastly expanded advertising section featuring especially major department stores. Women had previously been ignored, but now they were given multiple advice columns on family and household and fashion issues, and the advertising was increasingly pitched to them. [8][9]

France

1632 to 1815

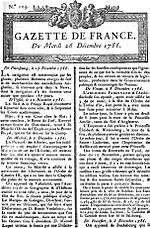

The first newspaper in France, the Gazette de France, was established in 1632 by the king's physician Theophrastus Renaudot (1586-1653), with the patronage of Louis XIII.[10] All newspapers were subject to prepublication censorship, and served as instruments of propaganda for the monarchy.

Under the ancien regime, the most prominent magazines were Mercure de France, Journal des sçavans, founded in 1665 for scientists, and Gazette de France, founded in 1631. Jean Loret was one of France's first journalists. He disseminated the weekly news of music, dance and Parisian society from 1650 until 1665 in verse, in what he called a gazette burlesque, assembled in three volumes of La Muse historique (1650, 1660, 1665). The French press lagged a generation behind the British, for they catered to the needs the aristocracy, while the newer British counterparts were oriented toward the middle and working classes.[11]

Periodicals were censored by the central government in Paris. They were not totally quiescent politically—often they criticized Church abuses and bureaucratic ineptitude. They supported the monarchy and they played at most a small role in stimulating the revolution.[12] During the Revolution new periodicals played central roles as propaganda organs for various factions. Jean-Paul Marat (1743–1793) was the most prominent editor. His L'Ami du peuple advocated vigorously for the rights of the lower classes against the enemies of the people Marat hated; it closed when he was assassinated. After 1800 Napoleon reimposed strict censorship.[13]

1815 to 1914

Magazines flourished after Napoleon left in 1815. Most were based in Paris and most emphasized literature, poetry and stories. They served religious, cultural and political communities. In times of political crisis they expressed and helped shape the views of their readership and thereby were major elements in the changing political culture.[14] For example, there were eight Catholic periodicals in 1830 in Paris. None were officially owned or sponsored by the Church and they reflected a range of opinion among educated Catholics about current issues, such as the 1830 July Revolution that overthrew the Bourbon monarchy. Several were strong supporters of the Bourbon kings, but all eight ultimately urged support for the new government, putting their appeals in terms of preserving civil order. They often discussed the relationship between church and state. Generally they urged priests to focus on spiritual matters and not engage in politics. Historian M. Patricia Dougherty says this process created a distance between the Church and the new monarch and enabled Catholics to develop a new understanding of church-state relationships and the source of political authority.[15]

20th century

The press was handicapped during the war by shortages of news, newsprint an young journalists, and by an abundance of censorship designed to maintain home front morale by minimizing bad war news. The Parisian newspapers were largely stagnant after the war; circulation inched up to 6 million a day from 5 million in 1910. The major postwar success story was Paris Soir; which lacked any political agenda and was dedicated to providing a mix of sensational reporting to aid circulation, and serious articles to build prestige. By 1939 its circulation was over 1.7 million, double that of its nearest rival the tabloid Le Petit Parisien. In addition to its daily paper Paris Soir sponsored a highly successful women's magazine Marie-Claire. Another magazine Match was modeled after the photojournalism of the American magazine Life. [16]

John Gunther wrote in 1940 that of the more than 100 daily newspapers in Paris, two (L'Humanité and Action Française's publication) were honest; "Most of the others, from top to bottom, have news columns for sale". He reported that Bec et Ongles was simultaneously subsidized by the French government, German government, and Alexandre Stavisky, and that Italy allegedly paid 65 million francs to French newspapers in 1935.[17] France was a democratic society in the 1930s, but the people were kept in the dark about critical issues of foreign policy. The government tightly controlled all of the media to promulgate propaganda to support the government's foreign policy of appeasement to the aggressions of Italy and especially Nazi Germany. There were 253 daily newspapers, all owned separately. The five major national papers based in Paris were all under the control of special interests, especially right-wing political and business interests that supported appeasement. They were all venal, taking large secret subsidies to promote the policies of various special interests. Many leading journalists were secretly on the government payroll. The regional and local newspapers were heavily dependent on government advertising and published news and editorials to suit Paris. Most of the international news was distributed through the Havas agency, which was largely controlled by the government.[18]

Britain

20th century

By 1900 popular journalism in Britain aimed at the largest possible audience, including the working class, had proven a success and made its profits through advertising. Alfred Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe (1865–1922), "More than anyone... shaped the modern press. Developments he introduced or harnessed remain central: broad contents, exploitation of advertising revenue to subsidize prices, aggressive marketing, subordinate regional markets, independence from party control.[19] His Daily Mail held the world record for daily circulation until his death. Prime Minister Lord Salisbury quipped it was "written by office boys for office boys".[20]

Socialist and labour newspapers also proliferated and in 1912 the Daily Herald was launched as the first daily newspaper of the trade union and labour movement.

Newspapers reached their peak of importance during the First World War, in part because wartime issues were so urgent and newsworthy, while members of Parliament were constrained by the all-party coalition government from attacking the government. By 1914 Northcliffe controlled 40 per cent of the morning newspaper circulation in Britain, 45 per cent of the evening and 15 per cent of the Sunday circulation.[21] He eagerly tried to turn it into political power, especially in attacking the government in the Shell Crisis of 1915. Lord Beaverbrook said he was, "the greatest figure who ever strode down Fleet Street." [22] A.J.P. Taylor, however, says, "Northcliffe could destroy when he used the news properly. He could not step into the vacant place. He aspired to power instead of influence, and as a result forfeited both."[23]

Other powerful editors included C. P. Scott of the Manchester Guardian, James Louis Garvin of The Observer and Henry William Massingham of the highly influential weekly magazine of opinion, The Nation.[24]

Germany

Denmark

Danish news media first appeared in the 1540s, when handwritten fly sheets reported on the news. In 1666, Anders Bording, the father of Danish journalism, began a state paper. The royal privilege to bring out a newspaper was issued to Joachim Wielandt in 1720. University officials handled the censorship, but in 1770 Denmark became one of the first nations of the world to provide for press freedom; it ended in 1799. The press in 1795–1814, led by intellectuals and civil servants, called out for a more just and modern society, and spoke out for the oppressed tenant farmers against the power of the old aristocracy.[25]

In 1834, the first liberal newspaper appeared, one that gave much more emphasis to actual news content rather than opinions. The newspapers championed the Revolution of 1848 in Denmark. The new constitution of 1849 liberated the Danish press. Newspapers flourished in the second half of the 19th century, usually tied to one or another political party or labor union. Modernization, bringing in new features and mechanical techniques, appeared after 1900. The total circulation was 500,000 daily in 1901, more than doubling to 1.2 million in 1925. The German occupation brought informal censorship; some offending newspaper buildings were simply blown up by the Nazis. During the war, the underground produced 550 newspapers—small, surreptitiously printed sheets that encouraged sabotage and resistance.[26]

The appearance of a dozen editorial cartoons ridiculing Mohammed set off Muslim outrage and violent threats around the world. (see: Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy) The Muslim community decided the caricatures in the Copenhagen newspaper Jyllands-Posten in September 2005 represented another instance of Western animosity toward Islam, and were so sacriligious that the perpetrators deserved severe punishment.[27][28]

The historiography of the Danish press is rich with scholarly studies. Historians have made insights into Danish political, social and cultural history, finding that individual newspapers are valid analytical entities, which can be studied in terms of source, content, audience, media, and effect.[29]

Russia

United States

Asia

China

Journalism in China before 1910 primarily served the international community. The main national newspapers in Chinese were published by Protestant missionary societies in order to reach the literati. Hard news was not their specialty, but they did train the first generation of Chinese journalists in Western standards of news gathering. editorials, and advertising.[30] Demands for reform and revolution was impossible for papers based inside China. Instead they appeared in polemical papers based in Japan, such as those edited by Liang Qichao (1873-1929). [31]

The overthrow of the old imperial regime in 1911 produced a surge in Chinese nationalism, an end to censorship, and a demand for professional, nation-wide journalism.[32] All the major cities launched such efforts. Special attention was paid to China's role in the World War. to the disappointing Paris Peace Conference of 1919, and to the aggressive demands and actions of Japan against Chinese interests. Journalists created professional organizations, and aspired to separate news from commentary. At the Press Congress of the World conference in Honolulu in 1921, the Chinese delegates were among the most Westernized and self-consciously professional journalists from the developing world. By the late 1920s, however, there was a much greater emphasis on advertising and expanding circulation, and much less interest in the sort of advocacy journalism that had inspired the revolutionaries.[33]

India

The first newspaper in India was circulated in 1780 under the editorship of James Augustus Hicky, named Hicky's Bengal Gazette.[34] On May 30, 1826 Udant Martand (The Rising Sun), the first Hindi-language newspaper published in India, started from Calcutta (now Kolkata), published every Tuesday by Pt. Jugal Kishore Shukla.[35][36] Maulawi Muhammad Baqir in 1836 founded the first Urdu-language newspaper the Delhi Urdu Akhbar. India's press in the 1840s was a motley collection of small-circulation daily or weekly sheets printed on rickety presses. Few extended beyond their small communities and seldom tried to unite the many castes, tribes, and regional subcultures of India. The Anglo-Indian papers promoted purely British interests. Englishman Robert Knight (1825–1890) founded two important English-language newspapers that reached a broad Indian audience, The Times of India and The Statesman. They promoted nationalism in India, as Knight introduced the people to the power of the press and made them familiar with political issues and the political process.[37]

Latin America and the Caribbean

British influence extended globally through its colonies and its informal business relationships with merchants in major cities. They needed up-to-date market and political information. The Diario de Pernambuco was founded in Recife, Brazil, in 1825.[38] El Mercurio was founded in Valparaiso, Chile, in 1827. The most influential newspaper in Peru, El Comercio, first appeared in 1839. The Jornal do Commercio was established in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 1827. Much later Argentina founded its newspapers in Buenos Aires: La Prensa in 1869 and La Nacion in 1870.[39]

In Jamaica, there were a number of newspapers that represented the views of the white planters who owned slaves. These newspapers included titles such as the Royal Gazette, The Diary and Kingston Daily Advertiser, Cornwall Chronicle, Cornwall Gazette, and Jamaica Courant.[40] In 1826, two free coloureds, Edward Jordan and Robert Osborn, founded The Watchman, which openly campaigned for the rights of free coloureds, and became Jamaica's first anti-slavery newspaper. In 1830, the criticism of the slave-owning hierarchy was too much, and the Jamaican colonial authorities arrested Jordan, the editor, and charged him with constructive treason. However, Jordan was eventually acquitted, and he eventually became Mayor of Kingston in post-Emancipation Jamaica.[41]

On the abolition of slavery in the 1830s, Gleaner Company was founded by two Jamaican Jewish brothers, Joshua and Jacob De Cordova, budding businessmen who represented the new class of light-skinned Jamaicans taking over post-Emancipation Jamaica.[42] While the Gleaner represented the new establishment for the next century, there was a growing black, nationalist movement that campaigned for increased political representation and rights in the early twentieth century. To this end, Osmond Theodore Fairclough founded Public Opinion in 1937. O.T. Fairclough was supported by radical journalists Frank Hill and H.P. Jacobs, and the first editorial of this new newspaper tried to galvanise public opinion around a new nationalism. Strongly aligned to the People's National Party (PNP), Public Opinion counted among its journalists progressive figures such as Roger Mais, Una Marson, Amy Bailey, Louis Marriott, Peter Abrahams, and future prime minister Michael Manley, among others.[43]

While Public Opinion campaigned for self-government, British prime minister Winston Churchill made it known he had no intention of presiding "over the liquidation of the British Empire", and consequently the Jamaican nationalists in the PNP were disappointed with the watered-down constitution that was handed down to Jamaica in 1944. Mais wrote an article saying "Now we know why the draft of the new constitution has not been published before," because the underlings of Churchill were "all over the British Empire implementing the real imperial policy implicit in the statement by the Prime Minister". The British colonial police raided the offices of Public Opinion, seized Mais's manuscript, arrested Mais himself, and convicted him of seditious libel, jailing him for six months.[44]

Radio and television

The history of radio broadcasting begins in the 1920s, and reached its apogee in the 1930s and 1940s. Experimental television was being studied before the 2nd world war, became operational in the late 1940s, and became widespread in the 1950s and 1960s, largely but not entirely displacing radio.

Internet journalism

The rapidly growing impact of the Internet, especially after 2000, brought "free" news and classified advertising to audiences that no longer cared for paid subscriptions. The Internet undercut the business model of many daily newspapers. Bankruptcy loomed across the U.S. and did hit such major papers as the Rocky Mountain news (Denver), the Chicago Tribune and the Los Angeles Times, among many others. Chapman and Nuttall find that proposed solutions, such as multiplatforms, paywalls, PR-dominated news gathering, and shrinking staffs have not resolved the challenge. The result, they argue, is that journalism today is characterized by four themes: personalization, globalization, localization, and pauperization.[45]

Historiography

Journalism historian David Nord has argued that in the 1960s and 1970s:

- "In journalism history and media history, a new generation of scholars . . . criticised traditional histories of the media for being too insular, too decontextualised, too uncritical, too captive to the needs of professional training, and too enamoured of the biographies of men and media organizations."[46]

In 1974, James W. Carey identified the 'Problem of Journalism History'. The field was dominated by a Whig interpretation of journalism history.

- "This views journalism history as the slow, steady expansion of freedom and knowledge from the political press to the commercial press, the setbacks into sensationalism and yellow journalism, the forward thrust into muck raking and social responsibility....the entire story is framed by those large impersonal forces buffeting the press: industrialisation, urbanisation and mass democracy.[47]

O'Malley says the criticism went too far, because there was much of value in the deep scholarship of the earlier period.[48]

See also

- History of newspaper publishing

- History of broadcasting

- Online newspaper

- Online magazine

- Newspaper

- News broadcasting

.jpg) Title page of Carolus' Relation from 1609, the earliest newspaper

Title page of Carolus' Relation from 1609, the earliest newspaper

Sources

- History of Journalism lecture notes by Dr. Wally Hastings, Northern State University, South Dakota

References

- ↑ Shannon E. Martin and David A. Copeland, eds. "The Function of Newspapers in Society: A Global Perspective (Praeger, 2003) p. 2

- ↑ Wan-Press.org, A Newspaper Timeline, World Association of Newspapers

- ↑ Infelise, Mario. "Roman Avvisi: Information and Politics in the Seventeenth Century." Court and Politics in Papal Rome, 1492-1700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. 212,214,216-217

- ↑ Thomas Schroeder, "The Origins of the German Press," in The Politics of Information in Early Modern Europe edited by Brendan Dooley and Sabrina Baron. (2001) 123-50, especially page 123

- ↑ Paul Arblaster, Posts, Newsletters, Newspapers: England in a European system of communications," Media History (2005) 11#1-2 pp: 21-36

- ↑ Carmen Espejo, "European Communication Networks in the Early Modern Age: A new framework of interpretation for the birth of journalism," Media History (2011) 17#2 pp 189-202

- ↑ "The Age of Journalism".

- ↑ Carlton J. H. Hayes, A Generation of Materialism, 1871-1900 (1941) pp 176-80.

- ↑ Rose F. Collins, and E. M. Palmegiano, eds. The Rise of Western Journalism 1815–1914: Essays on the Press in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Great Britain and the United States (2007)

- ↑ Gérard Jubert, Père des Journalistes et Médecin des Pauvres (2008)

- ↑ Stephen Botein, Jack R. Censer, and Harriet Ritvo, "The periodical press in eighteenth-century English and French society: a cross-cultural approach." Comparative Studies in Society and History 23#3 (1981): 464-490.

- ↑ Jack Censer, The French press in the age of Enlightenment (2002).

- ↑ Robert Darnton and Daniel Roche, eds., Revolution in Print: the Press in France, 1775–1800 (1989)

- ↑ Keith Michael Baker, et al., The French Revolution and the Creation of Modern Political Culture: The transformation of the political culture, 1789–1848 (1989).

- ↑ M. Patricia Dougherty, "The French Catholic press and the July Revolution." French History 12#4 (1998): 403-428.

- ↑ Hutton 2:692-94

- ↑ Gunther, John (1940). Inside Europe. New York: Harper & Brothers. pp. 179–180.

- ↑ Anthony Adamthwaite, Grandeur and Misery: France’s Bid for Power in Europe 1914-1940 (1995) pp 175-92.

- ↑ P.P. Catterall and Colin Seymour-Ure, "Northcliffe, Viscount." in John Ramsden, ed. The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-Century British Politics (2002) p 475.

- ↑ Oxford Dictionary of Quotations (1975).

- ↑ J. Lee. Thompson, "Fleet Street Colossus: The Rise and Fall of Northcliffe, 1896-1922." Parliamentary History 25.1 (2006): 115-138. online p 115.

- ↑ Lord Beaverbrook, Politicians and the War, 1914-1916 (1928) 1:93.

- ↑ A.J.P. Taylor, English History 1914-1945 (1965) p 27.

- ↑ A.J.P. Taylor, English History 1914-1945 (1965) pp 26-27.

- ↑ Thorkild Kjærgaard, "The rise of press and public opinion in eighteenth‐century Denmark—Norway." Scandinavian journal of History 14.4 (1989): 215-230.

- ↑ Kenneth E. Olson, The history makers: The press of Europe from its beginnings through 1965 (LSU Press, 1966) pp 50 – 64, 433

- ↑ Jytte Klausen, The Cartoons That Shook the World (Yale UP, 2009).

- ↑ Ana Belen Soage, "The Danish caricatures seen from the Arab world." Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions 7.3 (2006): 363-369. online

- ↑ Niels Thomsen, "Why Study Press History? A reexamination of its purpose and of Danish contributions." Scandinavian Journal of History 7.1-4 (1982): 1-13.

- ↑ Zhang Tao, "Protestant missionary publishing and the birth of Chinese elite journalism." Journalism Studies 8.6 (2007): 879-897.

- ↑ Natascha Vittinghoff, "Unity vs. uniformity: Liang Qichao and the invention of a" new journalism" for China." Late Imperial China 23.1 (2002): 91-143.

- ↑ Stephen MacKinnon, “Toward a History of the Chinese Press in the Republican Period,” Modern China 23#1 (1997) pp. 3-32

- ↑ Timothy B. Weston, "China, professional journalism, and liberal internationalism in the era of the First World War." Pacific Affairs 83.2 (2010): 327-347.

- ↑ Parthasarathy, Rangaswami (2011). Journalism in India. Sterling Publishers Pvt Ltd. p. 19. ISBN 9788120719934.

- ↑ Hena Naqvi (2007). Journalism And Mass Communication. Upkar Prakashan. pp. 42–. ISBN 978-81-7482-108-9.

- ↑ S. B. Bhattacherjee (2009). Encyclopaedia of Indian Events & Dates. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. pp. A119. ISBN 978-81-207-4074-7.

- ↑ Edwin Hirschmann, "An Editor Speaks for the Natives: Robert Knight in 19th Century India," Journalism Quarterly (1986) 63#2 pp 260-267.

- ↑ Pernambuco.com, O INÍCIO DA HISTÓRIA.

- ↑ E. Bradford Burns; Julie A. Charlip (2002). Latin America: A Concise Interpretive History. Prentice Hall. p. 151.

- ↑ Michael Siva, After the Treaties: A Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842, PhD Dissertation (Southampton: Southampton University, 2018), p. 279.

- ↑ https://jamaica-history.weebly.com/edward-jordon.html

- ↑ http://www.digjamaica.com/gleaner

- ↑ Ewart Walters, We Come From Jamaica: The National Movement, 1937-1962 (Ottawa: Boyd McRubie, 2014), pp. 65-69.

- ↑ Walters, We Come From Jamaica, pp. 69-70.

- ↑ Jane L. Chapman and Nick Nuttall, Journalism Today: A Themed History (Wiley-Blackwell, 2011) pp. 299, 313-314

- ↑ David Paul Nord, "The History of Journalism and the History of the Book," in Explorations in Communications and History, edited by Barbie Zelizer. (London: Routledge, 2008) p 164

- ↑ James Carey, "The Problem of Journalism History," Journalism History (1974) 1#1 pp 3,4

- ↑ Tom O'Malley, "History, Historians and the Writing Newspaper History in the UK c.1945–1962," Media History, (2012) 18#3 pp 289-310

Further reading

- Bösch, Frank. Mass Media and Historical Change: Germany in International Perspective, 1400 to the Present (Berghahn, 2015). 212 pp. online review

- Burrowes, Carl Patrick. "Property, Power and Press Freedom: Emergence of the Fourth Estate, 1640-1789," Journalism & Communication Monographs (2011) 13#1 pp2–66, compares Britain, France, and the United States

- Collins, Ross F. and E. M. Palmegiano, eds. The Rise of Western Journalism 1815–1914: Essays on the Press in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Great Britain and the United States (2007)

- Conboy, Martin. Journalism: A Critical History (2004)

- Crook; Tim. International Radio Journalism: History, Theory and Practice (Routledge, 1998) online

- Dooley, Brendan, and Sabrina Baron, eds. The Politics of Information in Early Modern Europe (Routledge, 2001)

- Lagerkvist, Johan. After the Internet, Before Democracy (2010), the media in China

- Lynch, Marc. Voices of the New Arab Public: Iraq, Al-Jazeera, and Middle East Politics Today (Columbia University Press 2006) online

- Peers Frank W. The Politics of Canadian Broadcasting, 1920–1951 (University of Toronto Press, 1969).

- Rugh, William A. Arab Mass Media: Newspapers, Radio, and Television in Arab Politics (Praeger, 2004) online

- Wolff, Michael. The Man Who Owns the News: Inside the Secret World of Rupert Murdoch (2008) 446 pages and text search, A media baron in Australia, UK and the US

Asia

- Huang, C. "Towards a broadloid press approach: The transformation of China's newspaper industry since the 2000s." Journalism 19 (2015): 1-16. online, With bibliography pages 27–33.

Britain

- Andrews, Alexander. The history of British journalism: from the foundation of the newspaper press in England, to the repeal of the Stamp act in 1855 (1859). online old classic

- Briggs Asa. The BBC—the First Fifty Years (Oxford University Press, 1984).

- Briggs Asa. The History of Broadcasting in the United Kingdom (Oxford University Press, 1961).

- Clarke, Bob. From Grub Street to Fleet Street: An Illustrated History of English Newspapers to 1899 (Ashgate, 2004)

- Crisell, Andrew An Introductory History of British Broadcasting. (2nd ed. 2002).

- Hale, Oron James. Publicity and Diplomacy: With Special Reference to England and Germany, 1890-1914 (1940) online pp 13-41.

- Herd, Harold. The March of Journalism: The Story of the British Press from 1622 to the Present Day (1952).

- Jones, A. Powers of the Press: Newspapers, Power and the Public in Nineteenth-Century England (1996).

- Lee, A. J. The Origins of the Popular Press in England, 1855–1914 (1976).

- Marr, Andrew. My trade: a short history of British journalism (2004)

- Scannell, Paddy, and Cardiff, David. A Social History of British Broadcasting, Volume One, 1922–1939 (Basil Blackwell, 1991).

- Silberstein-Loeb, Jonathan. The International Distribution of News: The Associated Press, Press Association, and Reuters, 1848–1947 (2014).

- Wiener, Joel H. "The Americanization of the British press, 1830—1914." Media History 2#1-2 (1994): 61-74.

British Empire

- Cryle, Denis. Disreputable profession: journalists and journalism in colonial Australia (Central Queensland University Press, 1997).

- Harvey, Ross. "Bringing the News to New Zealand: the supply and control of overseas news in the nineteenth century." Media History 8#1 (2002): 21-34.

- Kesterton, Wilfred H. A history of journalism in Canada (1967).

- Pearce, S. Shameless Scribblers: Australian Women's Journalism 1880–1995 (Central Queensland University Press, 1998).

- Sutherland, Fraser. The monthly epic: A history of Canadian magazines, 1789–1989 (1989).

- Vine, Josie. "If I Must Die, Let Me Die Drinking at an Inn': The Tradition of Alcohol Consumption in Australian Journalism" Australian Journalism Monographs (Griffith Centre for Cultural Research, Griffith University, vol 10, 2010) online; bibliography on journalists, pp 34–39

- Walker, R.B. The Newspaper Press in New South Wales: 1803–1920 (1976).

- Walker, R.B. Yesterday's News: A History of the Newspaper Press in New South Wales from 1920 to 1945 (1980).

- Walters, Ewart. We Come From Jamaica: The National Movement, 1937-1962 (Ottawa: Boyd McRubie, 2014).

France

- Censer, Jack. The French press in the age of Enlightenment (2002).

- Collins, Ross F. and E. M. Palmegiano, eds. The Rise of Western Journalism 1815–1914: Essays on the Press in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Great Britain and the United States (2007).

- Darnton, Robert and Daniel Roche, eds. Revolution in Print: the Press in France, 1775–1800 (1989)

- Jubin, George. "France, Journalism in, 1933." Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 10 (1933): 273-82. online

- Lehmann, Ulrich. "Le mot dans la mode: Fashion and literary journalism in Nineteenth-century France." (2009): 296-313. online

- Verboord, Marc, and Susanne Janssen. "Arts Journalism And Its Packaging In France, Germany, The Netherlands And The United States, 1955–2005." Journalism Practice 9#6 (2015): 829-852.

United States

- Barnouw Erik. The Golden Web (Oxford University Press, 1968); The Image Empire: A History of Broadcasting in the United States, Vol. 3: From 1953 (1970) excerpt and text search; The Sponsor (1978); A Tower in Babel (1966), to 1933, excerpt and text search; a history of American broadcasting

- Blanchard, Margaret A., ed. History of the Mass Media in the United States, An Encyclopedia. (1998)

- Craig, Douglas B. Fireside Politics: Radio and Political Culture in the United States, 1920–1940 (2005)

- Emery, Michael, Edwin Emery, and Nancy L. Roberts. The Press and America: An Interpretive History of the Mass Media 9th ed. (1999.), standard textbook; best place to start.

- Hampton, Mark, and Martin Conboy. "Journalism history—a debate" Journalism Studies (2014) 15#2 pp 154–171. Hampton argues that journalism history should be integrated with cultural, political, and economic changes. Conboy reaffirms the need for disentangling journalism history more carefully from media history.

- McCourt; Tom. Conflicting Communication Interests in America: The Case of National Public Radio (Praeger Publishers, 1999) online

- McKerns, Joseph P., ed. Biographical Dictionary of American Journalism. (1989)

- Marzolf, Marion. Up From the Footnote: A History of Women Journalists. (1977)

- Mott, Frank Luther. American Journalism: A History of Newspapers in the United States Through 250 Years, 1690-1940 (1941). major reference source and interpretive history. online edition

- Nord, David Paul. Communities of Journalism: A History of American Newspapers and Their Readers. (2001) excerpt and text search

- Schudson, Michael. Discovering the News: A Social History of American Newspapers. (1978). excerpt and text search

- Sloan, W. David, James G. Stovall, and James D. Startt. The Media in America: A History, 4th ed. (1999)

- Starr, Paul. The Creation of the Media: Political origins of Modern Communications (2004), far ranging history of all forms of media in 19th and 20th century US and Europe; Pulitzer prize excerpt and text search

- Streitmatter, Rodger. Mightier Than the Sword: How the News Media Have Shaped American History (1997)online edition

- Vaughn, Stephen L., ed. Encyclopedia of American Journalism (2007) 636 pages excerpt and text search

Magazines

- Angeletti, Norberto, and Alberto Oliva. Magazines That Make History: Their Origins, Development, and Influence (2004), covers Time, Der Spiegel, Life, Paris Match, National Geographic, Reader's Digest, ¡Hola!, and People

- Brooker, Peter, and Andrew Thacker, eds. The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines: Volume I: Britain and Ireland 1880–1955 (2009)

- Haveman, Heather A. Magazines and the Making of America: Modernization, Community, and Print Culture, 1741–1860 (Princeton University Press, 2015)

- Mott, Frank Luther. A History of American Magazines (five volumes, 1930–1968), detailed coverage of all major magazines, 1741 to 1930.

- Summer, David E. The Magazine Century: American Magazines Since 1900 (Peter Lang Publishing; 2010) 242 pages. Examines the rapid growth of magazines throughout the 20th century and analyzes the form's current decline.

- Wood, James P. Magazines in the United States (1971)

- Würgler, Andreas. National and Transnational News Distribution 1400–1800, European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History (2010).

Historiography

- Buxton, William J., and Catherine McKercher. "Newspapers, magazines and journalism in Canada: Towards a critical historiography." Acadiensis (1988) 28#1 pp. 103–126 in JSTOR; also online

- Daly, Chris. "The Historiography of Journalism History: Part 2: 'Toward a New Theory,'" American Journalism, Winter 2009, Vol. 26 Issue 1, pp 148–155, stresses the tension between the imperative form of business model and the dominating culture of news

- Dooley, Brendan. "From Literary Criticism to Systems Theory in Early Modern Journalism History," Journal of the History of Ideas (1990) 51#3 pp 461–86.

- Espejo, Carmen. "European Communication Networks in the Early Modern Age: A new framework of interpretation for the birth of journalism," Media History (2011) 17#2 pp 189–202

- Wilke, Jürgen: Journalism, European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History, 2013, retrieved: January 28, 2013.