Ha-ha

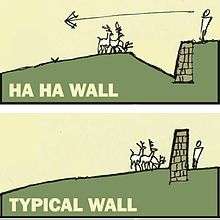

A ha-ha is a recessed landscape design element that creates a vertical barrier while preserving an uninterrupted view of the landscape beyond.

The design includes a turfed incline which slopes downward to a sharply vertical face, typically a masonry retaining wall. Ha-has are used in landscape design to prevent access to a garden, for example by grazing livestock, without obstructing views. In security design, the element is used to deter vehicular access to a site while minimizing visual obstruction.

The unusual name "ha-ha" is thought to have stemmed from the exclamations of surprise by those coming across them as the walls were designed to be invisible.[1]

Origins

Before mechanical lawn mowers, a common way to keep large areas of grassland trimmed was to allow livestock, usually sheep, to graze the grass. A ha-ha prevented grazing animals on large estates from gaining access to the lawn and gardens adjoining the house, giving a continuous vista to create the illusion that the garden and landscape were one and undivided.[2][3][4]

The basic design of sunken ditches is of ancient origin, being a feature of deer parks in England. The deer-leap or saltatorium consisted of a ditch with one steep side surmounted by a pale (picket-style fence made of wooden stakes) or hedge, which allowed deer to enter the park but not to leave. Since the time of the Norman conquest of England the right to construct a deer-leap was granted by the king, with reservations made as to the depth of the foss or ditch and the height of the pale or hedge.[5] On Dartmoor the deer-leap was known as a "leapyeat".[6]

The concept of the ha-ha is of French origin, with the term being attested in toponyms in New France from 1686 (as seen today in Saint-Louis-du-Ha! Ha!), and being a feature of the gardens of the Château de Meudon, circa 1700. The technical innovation was presented in Dezallier d'Argenville's La théorie et la pratique du jardinage (1709), which the architect John James (1712) translated into English:

Grills of iron are very necessary ornaments in the lines of walks, to extend the view, and to show the country to advantage. At present we frequently make thoroughviews, called Ah, Ah, which are openings in the walls, without grills, to the very level of the walks, with a large and deep ditch at the foot of them, lined on both sides to sustain the earth, and prevent the getting over; which surprises the eye upon coming near it, and makes one laugh, Ha! Ha! from where it takes its name. This sort of opening is haha, on some occasions, to be preferred, for that it does not at all interrupt the prospect, as the bars of a grill do.

The etymology of the term is generally given as being an expression of surprise—someone says "ha ha" or "ah! ah!" when they encounter such a feature. This is the explanation given in French, where it is traditionally attributed to Louis, Grand Dauphin, on encountering such features at Meudon, by d'Argenville (trans. James), above, and by Walpole, who surmised that the name is derived from the response of ordinary folk on encountering them and that they were "... then deemed so astonishing, that the common people called them Ha! Has! to express their surprise at finding a sudden and unperceived check to their walk." Thomas Jefferson, describing the garden at Stowe after his visit in April 1786, also uses the term with exclamation marks: "The inclosure is entirely by ha! ha!"[7]

In Britain, the ha-ha is a feature of the landscape gardens laid out by Charles Bridgeman and William Kent and was an essential component of the "swept" views of Capability Brown. Horace Walpole credits Bridgeman with the invention of the ha-ha but was unaware of the earlier French origins.

The contiguous ground of the park without the sunk fence was to be harmonized with the lawn within; and the garden in its turn was to be set free from its prim regularity, that it might assort with the wilder country without.[8]

During his excavations at Iona in the period 1964–1984, Richard Reece discovered an 18th-century ha-ha designed to protect the abbey from cattle.[9] Ice houses were sometimes built into ha-ha walls because they provide a subtle entrance that makes the ice house a less intrusive structure, and the ground provides additional insulation.[10]

Examples

Most typically, ha-has are still found in the grounds of grand country houses and estates. They keep cattle and sheep out of the formal gardens, without the need for obtrusive fencing. They vary in depth from about 0.6 m (2 ft) (Horton House) to 2.7 m (9 ft) (Petworth House).

An unusually long example is the ha-ha that separates the Royal Artillery Barracks Field from Woolwich Common in southeast London. This deep ha-ha was installed around 1774 to prevent sheep and cattle, grazing at a stopover on Woolwich Common on their journey to the London meat markets, from wandering onto the Royal Artillery gunnery range. A rare feature of this east-west ha-ha is that the normally hidden brick wall emerges above ground for its final 75 yards (70 metres) or so as the land falls away to the west, revealing a fine batter to the brickwork face of the wall, thus exposed. This final west section of the ha-ha forms the boundary of the Gatehouse[11] by James Wyatt RA. The Royal Artillery ha-ha is maintained in a good state of preservation by the Ministry of Defence. It is a Listed Building, and is accompanied by Ha-Ha Road that runs alongside its full length. There is a shorter ha-ha in the grounds of the nearby Jacobean Charlton House.

In Australia, ha-has were also used at Victorian-era lunatic asylums such as Yarra Bend Asylum, Beechworth Asylum, and Kew Lunatic Asylum. From the inside, the walls presented a tall face to patients, preventing them from escaping, while from outside they looked low so as not to suggest imprisonment.[12] For the patients themselves, standing before the trench, it also enabled them to see the wider landscape.[13] Kew Asylum has been redeveloped as apartments; however some of the ha-has remain, albeit partially filled in.

- Ha-ha variations used at Australian mental asylums

- Remains of the original ha-ha wall at Beechworth Asylum from the "outside" of the original asylum boundary

- From the inside, the ha-ha was a barrier to passage

- End view at the beginning of the remains of the ha-ha at Beechworth Asylum, showing the sloping trench

An example of the ha-ha variation used at Yarra Bend Asylum in Victoria, Australia, circa 1900

An example of the ha-ha variation used at Yarra Bend Asylum in Victoria, Australia, circa 1900

Ha-has were also used in North America. Only two historic installations remain in Canada, one of which is on the grounds of Nova Scotia's Uniacke House (1813), a rural estate built by Richard John Uniacke, an Irish-born Attorney-General of Nova Scotia.[14]

A 21st-century use of a ha-ha is at the Washington Monument to minimize the visual impact of security measures. After 9/11 and another unrelated terror threat at the monument, authorities had put up jersey barriers to prevent large motor vehicles from approaching the monument. The temporary barriers were later replaced with a new ha-ha, a low 0.76 m (30-inch) granite stone wall that incorporated lighting and doubled as a seating bench. It received the 2005 Park/Landscape Award of Merit.[15][16][17]

Legal

Personal injury

Due to the hidden nature of the ha-ha it can pose potential injury to the public as its initial design was to be invisible. This allowed the occupants of the house or any other building within the grounds to enjoy a clear and unobscured view of the land.

The Hopetoun House Preservation Trust

In 2008 during a participated guided walk to watch bats at night a participant of the walk suffered a severe fracture to the ankle after falling off a ha-ha wall whilst making their way back to the carpark.

A successful personal injury claim in the region of £35,000 was settled upon as the judge presiding the case deemed the ha-ha to be a dangerous man-made feature and it was up to the defenders to highlight the invisible danger that it presented.[18]

The presiding QC judge Alastair Campbell said he deemed a ha-ha wall to be outside the scope of the law over obvious dangers such as cliffs or canals where an occupier is not required to take precautions against a person being injured. This was due to it being an unusual man made feature, that the public would be very much unaware of its existence, especially across a wide lawn.[19]

Manor house

In 2014 a wedding guest at a manor house injured themselves whilst making their way across the manor garden. They fell off the ha-ha and displaced their right tibia and fibula bones, which required surgical open reduction and fixation. The guest brought a successful personal injury claim. This was investigated by the environmental health department, who agreed that the area should have been lit up in some way to avoid this kind of accident.[20]

The defendants in the litigation case were quick to admit liability for the incident, and settled for about £10,000. This was followed by radical changes to the signposting and lighting around the ha-ha to let visitors know of its presence.[20]

Preventative ha-ha repairs

Sunbury Park

Emergency repairs to the ha-ha wall at Sunbury Park in Spelthorne took place in 2009, after the council realised that they would be liable for any injury or death caused by the ha-ha wall.

Surrounding vegetation was removed two years before the works opened up the ha-ha to the public. However environmental services were made aware that the ha-ha was in a state of disrepair, and without appropriate warning signs.

Initial attempts to obtain funding from the heritage lottery fund were abandoned, after it was realised that the repairs needed to be immediate and awaiting funding would delay the project, potentially exposing the council to legal and liability claims for any injuries.

The total cost of repairs was thought to be around £65,000; environmental services contributed £9,000, and the rest of the funds was taken from capital monies.[21]

Dalzell Estate

In 2016 the Ha-Ha wall in Dalzell estate was urgently repaired after it became unsafe after the stonework collapsed. The council's Environmental Services Committee were concerned about potential liability and personal injury claims and enlisted the help of volunteers and staff from a local charity to repair the ha-ha wall within the estate.

The repair project received funding from the environmental key fund and the heritage lottery fund via the Clyde and Avon Valley Landscape Partnership.[22]

See also

- Cattle guard

- Moat

- Royal Crescent, Bath, England

- Retaining wall

References

| Look up haha in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ha-has. |

- ↑ "BBC - Legacies - Architectural Heritage - England - Teesside - What's so funny about a ha-ha wall? - Article Page 1". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- ↑ West Dean College: "From the front the parkland landscape appears continuous, but in fact the formal grounds are protected from the grazing sheep and cattle by a ha-ha"

- ↑ "Lawn Pros and Cons". Pat Welsh. Retrieved 2013-04-15.

- ↑ Massachusetts Agriculture Archived 2009-01-16 at the Wayback Machine.: "Early suburbanites relied on hired help to scythe the grass or sheep to graze the lawn. The lawn mower ... made it possible for homeowners to maintain their own lawn. ... The ha-ha provided an invisible barrier ... which kept livestock from wandering ... into gardens. "

- ↑ Shirley, Evelyn Philip (1867). "1 Deer and deer parks". Some account of English deer parks: with notes on the management of deer. London: John Murray. p. 14. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- ↑ Anon. "Okehampton Deer Park". Legendary Dartmoor. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ↑ The Papers of Thomas Jefferson Digital Edition, ed. Barbara B. Oberg and J. Jefferson Looney. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, Rotunda, 2008, p. 371. Online edition accessed 14 Aug 2012.

- ↑ Horace Walpole, Essay upon modern gardening Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine., 1780

- ↑ Hamlin, Ann (1987). Iona: a view from Ireland. Proc Soc Antiq Scot, ISSN 0081-1564, V. 117, P. 17

- ↑ Walker, Bruce (1978). Keeping it cool. Scottish Vernacular buildings Working Group. Edinburgh & Dundee. Pages 564-565

- ↑ Large and Associates website

- ↑ "Kew Lunatic Asylum - Historic Walk] Australian Science Archives Project, [Kew Lunatic Asylum".

- ↑ Semple Kerr, James (1988). Out of Sight, Out of Mind: Australia's places of confinement, 1788-1988. National Trust of Australia. p. 158. ISBN 0 947137 80 7.

- ↑ Anon. "About Uniacke Estate". Nova Scotia Museum. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- ↑ Washington Monument Archived 2016-04-30 at the Wayback Machine. (from the OLIN website)

- ↑ Monumental Security (from the American Society of Landscape Architects website, April 10, 2006)

- ↑ "Risk Management Series: Site and Urban Design for Security, , page 4-17". U. S. Department Security, Federal Emergency Agency.

- ↑ "JOHN COWAN v. THE HOPETOUN HOUSE PRESERVATION TRUST AND OTHERS". www.scotcourts.gov.uk.

- ↑ "Bat walk man wins damages after ditch fall". HeraldScotland. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- 1 2 "Personal injury team secures compensation for Manor House guest". www.penningtons.co.uk.

- ↑ "Ha-Ha Repairs" (PDF).

- ↑ Service Manager, Scott House (2016-06-23). "Volunteers restore historic feature". Retrieved 2017-11-29.