Hansel and Gretel

"Hansel and Gretel" (/ˈhænsəl,

Plot

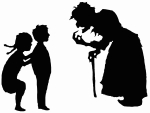

The story is set in medieval Germany. Hansel and Gretel are the children of a poor woodcutter. When a famine settles over the land, the woodcutter's wife decides to take the children into the woods and leave them there to fend for themselves, so that she and her husband do not starve to death. The woodcutter opposes the plan but finally reluctantly submits to his wife's scheme. They were unaware that in the children's bedroom, Hansel and Gretel have overheard them. After the parents have gone to bed, Hansel sneaks out of the house and gathers as many white pebbles as he can, then returns to his room, reassuring Gretel that God will not forsake them.

The next day, the family walk deep into the woods and Hansel lays a trail of white pebbles. After their parents abandon them, Hansel and Gretel follow the trail back home. When their mother sees them she is furious and locks them in the house. Hansel and Gretel are unable to escape or even simply collect pebbles.

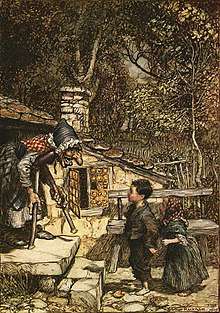

The following morning, the family treks into the woods. Hansel takes a slice of bread and leaves a trail of bread crumbs for them to follow home. However, after they are once again abandoned, they find that birds have eaten the crumbs and they are lost in the woods. After days of wandering, they follow a beautiful white bird to a clearing in the woods, and discover a large cottage built of gingerbread, cakes, candy and with window panes of clear sugar. Hungry and tired, the children begin to eat the rooftop of the house, when the door opens and a hideous old hag emerges and lures the children inside, with the promise of soft beds and delicious food and a hot bath. They do this unaware that their hostess is a bloodthirsty witch who waylays children to cook and eat them.

The next morning, the witch cleans out the cage in the garden from her previous captive. Then she throws Hansel into the cage and forces Gretel into becoming her slave. The witch feeds Hansel regularly to fatten him up. Hansel realizes this and uses the witch's tendency to his advantage. Every time the witch checks how fat Hansel is, by way of seeing Hansel's finger, he sticks out a bone he finds in the cage. Due to the witch's blindness, she is fooled into thinking Hansel is too thin to eat. After weeks of the same result, the witch grows impatient and decides to eat Hansel anyway.

The next day, the witch prepares the oven for Hansel, but decides she is hungry enough to eat Gretel too. She coaxes Gretel to the open oven and prods her to lean over in front of it to see if the fire is hot enough. Gretel, sensing the witch's intent, pretends she does not understand what she means. Infuriated, the witch demonstrates, and Gretel pushes her into the oven. She bolts the door shut, leaving "the ungodly creature to be burned to ashes", screaming in pain until she dies. Gretel frees Hansel from the cage and the pair discover a vase full of treasure and precious stones. Putting the jewels into their clothing, the children set off for home.

A duck ferries them across an expanse of water and at home they find only their father who revealed that their mother died from an unknown cause. Their father had spent all his days lamenting the loss of his children and is delighted to see them safe and sound. With the witch's wealth, they all live happily ever after.

History and analysis

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm heard "Hansel and Gretel" from Wilhelm's friend (and future wife) Dortchen Wild[1] and published it in Kinder- und Hausmärchen in 1812.[2] In the Grimms' version of the tale, the woodcutter's wife is the children's biological mother and the blame for abandoning them is shared between both her and the woodcutter himself. In later editions, some slight revisions were made: the wife became the children's stepmother, the woodcutter opposes her scheme to abandon the children and religious references are made. The sequence where the swan helps them across the river is also an addition to later editions. Another revision was that some versions claimed the mother died from unknown causes, left the family, or remained with the husband at the end of the story. [3]

The fairy tale may have originated in the medieval period of the Great Famine (1315–1321),[4] which caused desperate people to abandon young children to fend for themselves, or even resort to cannibalism.

Folklorists Iona and Peter Opie indicate in The Classic Fairy Tales (1974) that "Hansel and Gretel" belongs to a group of European tales especially popular in the Baltic regions, about children outwitting ogres into whose hands they have involuntarily fallen. The tale bears resemblances to the first half of Charles Perrault's "Hop-o'-My-Thumb" (1697) and Madame d'Aulnoy's "Finette Cendron" (1721). In both tales, the Opies note, abandoned children find their way home by following a trail. In "Clever Cinders", the Opies observe that the heroine incinerates a giant by shoving him into an oven in a manner similar to Gretel's dispatch of the witch and they point out that a ruse involving a twig in a Swedish tale resembles Hansel's trick of the dry bone. Linguist and folklorist Edward Vajda has proposed that these stories represent the remnant of a coming-of-age rite-of-passage tale extant in Proto-Indo-European society.[5][6] A house made of confectionery is found in a 14th-century manuscript about the Land of Cockayne.[1]

The fact that the mother or stepmother dies when the children have killed the witch has suggested to many commentators that the mother or stepmother and the witch are metaphorically the same woman.[7]

In the Russian Vasilisa the Beautiful, the stepmother likewise sends her hated stepdaughter into the forest, to borrow a light from her sister, who turns out to be Baba Yaga, who is also a cannibalistic witch. Besides highlighting the endangerment of children (as well as their own cleverness), the tales have in common a preoccupation with food and with hurting children: the mother or stepmother wants to avoid hunger, while the witch lures children to eat her house of candy so that she can then eat them.[8] Another tale of this type is the French fairy tale The Lost Children.[9] The Brothers Grimm also identified the French Finette Cendron and Hop o' My Thumb as parallel stories.[10]

Cultural significance

Hansel and Gretel's trail of breadcrumbs inspired the name of the navigation element "breadcrumbs" that allows users to keep track of their locations within programs or documents.[11] The opera Hänsel und Gretel by Engelbert Humperdinck is one of the most renowned operas, and is considered one of the most important German operas.[12]

See also

Notes

- ↑ In German, the names are diminutives of Johannes ("John") and Margarete ("Margaret"), respectively

References

Citations

- 1 2 Opie & Opie 1974, p. 237

- ↑ Tatar (2002), p. 44

- ↑ Tatar (2002), p. 45

- ↑ Raedisch (2013), p. 180

- ↑ Vajda (2010)

- ↑ Vajda (2011)

- ↑ Lüthi 1970, p. 64

- ↑ Tatar 2002, p. 54

- ↑ Delarue 1956, p. 365

- ↑ Tatar 2002, p. 72

- ↑ Mark Levene (18 October 2010). An Introduction to Search Engines and Web Navigation (2nd ed.). Wiley. p. 221. ISBN 978-0470526842. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- ↑ Upton, George Putnam (1897). The Standard Operas (Google book) (12th ed.). Chicago: McClurg. pp. 125–129. ISBN 1-60303-367-X. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

Sources

- Delarue, Paul (1956). The Borzoi Book of French Folk-Tales. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

- Lüthi, Max (1970). Once Upon A Time: On the Nature of Fairy Tales. Frederick Ungar Publishing Co.

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1974). The Classic Fairy Tales. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-211559-1.

- Raedisch, Linda (2013). The Old Magic of Christmas: Yuletide Traditions for the Darkest Days of the Year. Llewellyn Worldwide.

- Tatar, Maria (2002). The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales. BCA. ISBN 978-0-393-05163-6.

- Vajda, Edward (26 May 2010). The Classic Russian Fairy Tale: More Than a Bedtime Story (Speech). The World's Classics. Western Washington University.

- Vajda, Edward (1 February 2011). The Russian Fairy Tale: Ancient Culture in a Modern Context (Speech). Center for International Studies International Lecture Series. Western Washington University.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hansel and Gretel. |

- Project Gutenberg e-text

- SurLaLune Fairy Tale Pages: The Annotated Hansel and Gretel

- Original versions and psychological analysis of classic fairy tales, including Hansel and Gretel

- The Story of Hansel and Gretel

- Collaboratively illustrated story on Project Bookses

- A translation of the Grimm's Fairy Tale Hansel and Gretel