German wine classification

The bottle on the right uses a slightly different order: Region (Rheingau) and variety (Riesling) - vintage - village (Kiedrich) and vineyard (Gräfenberg) - Prädikat (Auslese) - producer (Weingut Robert Weil) - volume and alcoholic strength

The German wine classification system puts a strong emphasis on standardization and factual completeness, and was first implemented per the German Wine Law of 1971. Almost all of Germany's vineyards are delineated and registered as one of approximately 2,600 Einzellagen ('individual sites'), and the produce from one can be used to make German wine at any quality level, depending not on yields but on the ripeness, or must weight of the grapes.[1]

In a country as far north as Germany, the ripeness of grapes varies tremendously and profoundly affects the types of wine that can be produced. The ripeness categories are referred to as "quality levels," which is a misnomer - ripeness is always a clue to a wine's body, but not necessarily a predictor of its quality. Also, ripeness is determined by sugar content at harvest and does not reflect the sugar content in the final wine. Thus a wine in any of the German categories can be dry (trocken) or fairly dry (halbtrocken.)[2]

The quality system of wines has been reorganized since 1 August 2009 by the EU wine market organization. The traditional German wine classification was superseded by an origin-related system (Terroir). The already existing protection of geographical indication was transmitted through this step as well to the wine classification.[3]

Quality designations

There are two major categories of German wine: table wine and "quality" wine. Table wine includes the designations tafelwein and landwein. These are rock bottom categories of inexpensive, light, neutral wine. Unlike the supposed equivalents of "Vin de Table" / "Vino da Tavola" and "Indicazione Geografica Tipica" / "Vin de Pays", exciting things are rarely made, production levels are not high, and these wines are typically exported to the United States. In 2005, Tafelwein and Landwein only accounted for 3.6% of total production.[4]

Quality wine is divided into two types:

- Qualitätswein, or quality wine from a specific region.

- This is wine from one of the 13 wine-growing regions (Anbaugebiete), and the region must be shown on the label. It is a basic level of everyday, mostly inexpensive quaffing wines. The grapes are at a fairly low level of ripeness, with must weights of 51°Oe to 72°Oe. The alcohol content of the wine must be at least 7% by volume, and chaptalization (adding sugar to the unfermented grape juice to boost the final alcohol level, which in no way alters the sweetness) is often used. Qualitätswein range from dry to semi-sweet, and the style is often indicated on the label, along with the designation Qualitätswein and the region. Some top-level dry wines are officially Qualitätswein although they would qualify as Prädikatswein.[5]

- Prädikatswein, or superior quality wine.

- Known as Qualitätswein mit Prädikat (QmP) (quality wine with specific attributes) until August 2007, this is the top level of German wines. These prominently display a Prädikat (ripeness level designation) on the label and may not be chaptalized. Prädikatswein range from dry to intensely sweet, but unless it is specifically indicated that the wine is dry or off-dry, these wines always contain a noticeable amount of residual sugar. Prädikatswein must be produced from allowed varieties in one of the 39 subregions (Bereich) of one of the 13 wine-growing regions, although it is the region rather than the subregion which is mandatory information on the label. (Some of the smaller regions, such as Rheingau, consist of only one subregion.)

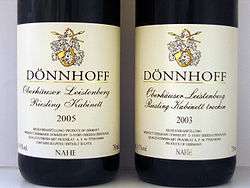

The different Prädikat (superior quality wine) designations used are as followed, in order of increasing sugar levels in the must:

- Kabinett - literally "cabinet", meaning wine of reserve quality to be kept in the vintner's cabinet

- fully ripened light wines from the main harvest, typically semi-sweet with crisp acidity, but can be dry if designated so.

- Spätlese - meaning "late harvest"

- typically half-dry, often (but not always) sweeter and fruitier than Kabinett. The grapes are picked at least 7 days after normal harvest, so they are riper. While waiting to pick the grapes carries a risk of the crop being ruined by rain, in warm years and from good sites much of the harvest can reach Spätlese level. Spätlese can be a relatively full-bodied dry wine if designated so. While Spätlese means late harvest the wine is not as sweet as a dessert wine, as the "late harvest" term is often used in US wines.

- Auslese - meaning "select harvest"

- made from very ripe, hand selected bunches, typically semi-sweet or sweet, sometimes with some noble rot character. Sometimes Auslese is also made into a powerful dry wine, but the designation Auslese trocken has been discouraged after the introduction of Grosses Gewächs. Auslese is the Prädikat which covers the widest range of wine styles, and can be a dessert wine.

- Beerenauslese - meaning "select berry harvest"

- made from overripe grapes individually selected from bunches and often affected by noble rot, making rich sweet dessert wine.

- Trockenbeerenauslese - meaning "select dry berry harvest" or "dry berry selection"

- made from selected overripe shrivelled grapes often affected by noble rot making extremely rich sweet wines. "Trocken" in this phrase refers to the grapes being dried on the vine rather than the resulting wine being a dry style.

- Eiswein (ice wine)

- made from grapes that have been naturally frozen on the vine, making a very concentrated wine. Must reach at least the same level of sugar content in the must as a Beerenauslese. The most classic Eiswein style is to use only grapes that are not affected by noble rot. Until the 1980s, the Eiswein designation was used in conjunction with another Prädikat (which indicated the ripeness level of the grapes before they had frozen), but is now considered a Prädikat of its own.

The minimum must weight requirements for the different Prädikat designations are as follows.[6] Many producers, especially top-level producers, exceed the minimum requirements by a wide margin.

Prädikat Minimum must weight Examples of requirements Minimum alcohol level in the wine Dependent on grape variety and wine-growing region Riesling from Mosel Riesling from Rheingau Kabinett 67-82°Oe 70°Oe 73°Oe 7% Spätlese 76-90°Oe 76°Oe 85°Oe 7% Auslese 83-100°Oe 83°Oe 95°Oe 7% Beerenauslese, Eiswein 110-128°Oe 110°Oe 125°Oe 5.5% Trockenbeerenauslese 150-154°Oe 150°Oe 150°Oe 5.5%

This does not necessarily determine the sweetness of the final wine, because the winemaker may choose to ferment the wine fully or let some residual sugar remain.

Additional designations

Wines can bear additional designation based on their sugar content or color.

Sweetness of the wine

The sugar content in the finished wine can be indicated by the following designations for Qualitätswein and Prädikatswein.[7] For sparkling wines (Sekt), many of the same designations are used, but have a different meaning.

Designation English translation Maximum sugar level allowed Low acid wines Medium acid wines High acid wines trocken dry 4 grams per liter acid level in grams per liter + 2 9 grams per liter halbtrocken half-dry 12 grams per liter acid level in grams per liter + 10 18 grams per liter feinherb off-dry Unregulated designation, slightly sweeter than halbtrocken lieblich, mild or restsüß semi-sweet Usually not specially marked as such on the label.

Follows by default from their Prädikat in the absence of the above designations.süß or edelsüß sweet Usually not specially marked as such on the label.

Follows by default from their Prädikat in the absence of the above designations.

Color

There are also color designations that can be used on the label:[8]

- Weißwein - white wine

- May be produced only from white varieties. This designation is seldom used.

- Rotwein - red wine

- May be produced only from red varieties with sufficient maceration to make the wine red. Sometimes used for clarification if the producer also makes rosés from the same grape variety.

- Roséwein - rosé wine

- Produced from red varieties with a shorter maceration, the wine must have pale red or clear red color.

- Weißherbst - rosé wine or blanc de noirs

- A rosé wine which must conform to special rules: must be Qualitätswein or Prädikatswein, single variety and be labelled with the varietal name. There are no restrictions as to the color of the wine, so they range from pale gold to deep pink. Weißherbst wines also range from dry to sweet, such as rosé Eiswein from Spätburgunder.

Extra ripeness or higher quality

Some producers also use additional propriate designations to denote quality or ripeness level within a Prädikat. These are out of the scope of the German wine law. Especially for Auslese, which can cover a wide range of sweetness levels, the presence of any of these designations tends to indicate a sweet dessert wine rather than a semi-sweet wine. These designations are all unregulated.

- Goldkapsel - gold capsule

- A golden capsule or foil on the bottle. Denotes a wine considered better by the producer. Usually means a Prädikatswein that is sweeter or more intense, or indicates an auction wine made in a very small lot.

- Stars *, ** or ***

- Usually means that a Prädikatswein has been harvested at a higher level of ripeness than the minimum required, and can mean that the wine is sweeter or more intense.

- Fuder (vat) numbers

- Usually indicated for better wines and often the numbers are arranged in some logical order, although the same numbers need not return in each vintage. This practice seems to be most common for semi-sweet and sweet wines in the Mosel region.

Special and regional wine types

There are also a number of specialty and regional wines, considered as special version of some quality category.[9] Here are some of them:

- Liebfraumilch or Liebfrauenmilch

- A semi-sweet Qualitätswein from the Rheingau, Nahe, Rheinhessen or Pfalz, consisting at least 70% of the varieties Riesling, Müller-Thurgau, Silvaner or Kerner. In practice there is very little Riesling in Liebfraumilch since varietally labelled Riesling wines tend to fetch a higher price. Liebfraumilch may not carry a varietal designation on the label. Liebfraumilch is probably Germany's most notorious wine type, and is in principle a medium-quality wine designation although more commonly perceived to be a low-quality wine both at home and on the export market.

- Moseltaler

- An off-dry/semi-sweet Qualitätswein cuvée from the Mosel wine region (Moseltal is Moselle Valley in German) made from the following white grape varieties: Riesling, Müller-Thurgau, Elbling and Kerner. May not carry a varietal designation on the label, and sold under a uniform logotype. Must have a residual sugar of 15-30 grams per liter and a minimum acidity of 7 grams per liter. Basically a Liebfraumilch-lookalike from Mosel.

- Riesling Hochgewächs - Riesling high growth

- A varietally pure Riesling Qualitätswein with at least 1.5% (approx 10°Oe) higher potential alcohol than the minimum requirements for Qualitätswein in the region. Must also receive a higher grade (3 out of 5 rather than 1.5 out of 5) in the mandatory quality testing.

- Rotling

- A wine produced from a mixture of red and white varieties. A Rotling must have pale red or clear red color

- Schillerwein

- A Rotling from the Württemberg wine-growing region, which must be Qualitätswein or Prädikatswein.

- Badisch Rotgold

- A Rotling from the Baden wine-growing region, which must be Qualitätswein or Prädikatswein. It must be made from Grauburgunder and Spätburgunder and the varieties must be specified on the label.

New classes for dry wines

There are three classes for dry wines with official status:

- Classic

- Introduced with the 2000 vintage, Classic is in principle a dry or slightly off-dry Qualitätswein that conforms to slightly higher standards intended to make it food-friendly. It must be made from varieties considered classical in its region, have a potential alcohol of 1% (or 8°Oe) above the minimum requirements for its variety and region, and have an alcohol level of minimum 12.0% by volume, except in Mosel, where the minimum level is 11.5%. Maximum sugar level is twice the acid level, but no more than 15 grams per liter.[10][11]

- Selection

- Is a dry wine with a must weight of at least Auslese level, from a selected vineyard site or parcels thereof. Grapes have to be harvested by hand with a maximum yield of 60hl/ha. Residual sugar level in a 'Selection' wine is a maximum of 9 grams per liter, with the exception of Riesling wines that can have up to 12 grams per liter, based on the acidity level of the wine.[12]

- Erstes Gewächs

- (first class growth), a designation used only in Rheingau for top-level dry wines (the maximum permitted amount of residual sugar is 13 g/L), hand-harvested from selected sites.

The following designations are not official, but have become increasingly used in recent years:

- Großes Gewächs

- (great growth), a designation used by VDP members (stylized as VDP.Grosses Gewächs) in all regions to designate top-level dry wines from sites classified as Grosse Lage. Used by the organisation Bernkasteler Ring for the same purpose in Mosel.

- Grosse Lage

- (Grand cru), a designation used by the VDP to designate non-dry wines from Grosse Lage sites. The non-dry wines are always of Prädikatswein level with the Prädikat mentioned, e.g. VDP.Grosse Lage Spätlese.

- Erste Lage

- (Premier cru), a designation used by VDP in all regions except Mosel and Rheingau to denote selected sites suitable for Erste Lage wines.

- Charta Riesling

- a 100% Rheingau Riesling of Qualitätswein or Prädikatswein quality with a residual sugar ranging from 9-18 grams/liter (off-dry) and a minimum acidity of 7.5 grams/liter. The wines must achieve higher starting must weights than required by law and undergo sensory testing by a special panel (in addition to the A.P.Nr. procedure). Uniform packaging.

Historical classifications no longer in use

Several terms went out of use with the 1971 wine law, but since many riesling wines can be successfully cellared for many decades, some of these designations may still be encountered on bottles.

- Cabinet, or sometimes Kabinettwein[13]

- A better wine that has been set aside by the producer for later sale, corresponding to the use of the term Reserve in many countries. Often used in conjunction with a Prädikat, so terms like "Trockenbeerenauslese Cabinet", which makes no sense whatsoever under the 1971 wine law, can be found on older bottles. The term Kabinett was not used in its later-day sense before the 1971 wine law.

- Naturwein or Naturrein; natural wine or naturally pure[14]

- Designates a wine that has not been chaptalized. If no prädikat is used, it corresponds roughly to a post-1971 Kabinett, but can sometimes be drier (such as halbtrocken).

- Edelbeerenauslese

- Corresponds to Trockenbeerenauslese. Strangely enough, although Edelbeeren means noble berries, and Trockenbeeren means dry berries, Edelbeerenauslese has been used for sun-dried grapes rather than grapes affected by noble rot.

- Eiswein Kabinett, Eiswein Spätlese, Eiswein Auslese, Eiswein Beerenauslese, Eiswein Trockenbeerenauslese

- Before 1982, Eiswein was used together with another Prädikat, which denoted the must weight of the grapes before they froze. Since 1982, Eiswein is a Prädikat in its own right, with minimum must weights applied after freezing.

Geographic classification

The geographic classification is different for Landwein, Deutscher Wein, Qualitätswein and Prädikatswein.

Geographic classification for Deutscher Wein (formerly Tafelwein) and Landwein

There are seven Deutscher Wein regions: Rhein-Mosel, Bayern, Neckar, Oberrhein, Albrechtsburg, Stargarder Land and Niederlausitz. These are divided into a number of subregions, which in turn are divided into 19 Landwein regions (and must be trocken or halbtrocken in style). (There is no Landwein region for Franken.) Names of individual vineyards are not used for Deutscher Wein or Landwein. Deutscher Wein must be 100% German in origin, or specifically state on the label were grapes were sourced from within the European Union. Sparkling wine produced at the Deutscher Wein level is often labeled as Deutscher Sekt and is made from 100% German grapes/wine.

Geographic classification for Qualitätswein and Prädikatswein

There are four levels of geographic classification, and any level of classification can be used on the label of Qualitätswein and Prädikatswein:

- Anbaugebiet, wine growing regions, of which there are 13. Anbaugebiet is always indicated on the label of Qualitätswein and Prädikatswein.

- Bereich, district, of which there are 39. Each Anbaugebiet is divided into one or more Bereiche.

- Großlage, collective site, which is a collective name for a number of single vineyards, and which number about 170.

- Einzellage, single vineyard, of which there are about 2 600.

The names of Großlagen and Einzellagen are always used together with the name of a wine village, because some Einzellage names, such as Schlossberg (castle hill) are used in several villages. Unfortunately, it is not possible to tell a Großlage from an Einzellage just by looking at the wine label. A few examples of how the names appear on labels:

- The vineyard Sonnenuhr (meaning "sun dial") in the village Wehlen along the Mosel is designated as Wehlener Sonnenuhr.

- The neighbouring village Zeltingen also has a vineyard called Sonnenuhr, and will appear on the label as Zeltinger Sonnenuhr.

- Both these vineyards belong to Großlage Münzlay, which is assigned to the village Wehlen. A wine from any of these vineyards, or a blend from both of them, can be sold under the name Wehlener Münzlay.

- These vineyards lie within Bereich Bernkastel, which provides an additional choice for labelling.

- It is also possible to simply label the wine as a wine from Anbaugebiet Mosel.

There are a few exceptions to the rule that a village must be indicated together with the vineyard name, those are a handful of historical vineyards known as Ortsteil im sinne des Weingesetzes (village name in sense of the wine law). Examples are Schloss Johannisberg in Rheingau and Scharzhofberg along the Saar. They are of the same size as a typical Einzellage and could be thought of as Einzellagen which were so famous that they were excused from displaying the village name.

Labels

A German wine label can offer a wealth of information for the consumer, despite the reputation they traditionally have of confusing laymen. Jon Bonné, MSNBC Life Style editor describes German wine labels as a "thicket of exotic words and abbreviations" that require "the vinous equivalent of Cliff notes to parse."

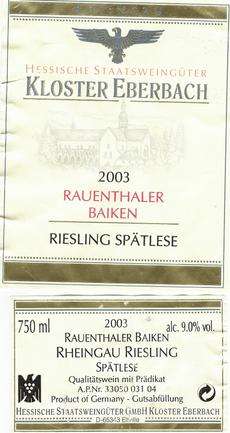

Required Information

German wine law regulates that at least six items of information be present on the label.

- Name of the producer or bottler (e.g.: Staatsweingüter Kloster Eberbach)

German wine domaines/"châteaux" are often called "Kloster", "Schloss", "Burg", "Domaine" or "Weingut" followed by some other name.

- A.P.Nr Amtliche Prüfnummer Quality control number (e.g.: 33050 031 04)

The first number (1-9) relates to the German wine region where the wine was produced and tested (e.g. 3-Rheingau). The second 2 or 3 digit number indicates the village of the vineyard (e.g. 30-Rauenthal)). The next two digits represents the particular wine estate (e.g. 50-Kloster Eberbach). The following 2 to 3 digit number is the sequential order that the wine was submitted by that producer for testing (e.g. 031 - this was the 31st wine submitted by Kloster Eberbach for testing). The final two digits is the year of the testing, which is normally the year following the vintage (e.g. 04 - the wine was tested in 2004).

- Anbaugebiet, i.e. region of origin (e.g.: Rheingau)

- Volume of the wine (e.g.: 750ml)

- Location of the producer/bottler (e.g.: Eltville)

- Alcohol level (e.g.: 9.0% vol)

Additional information

Though not required, German wine labels may also include

- Grape variety (e.g., Riesling)

- Prädikat level of ripeness (e.g., Spätlese)

- Vintage year (e.g., 2003)

- Taste, such as dry (trocken) or off-dry (halbtrocken)

- Vineyard name (e.g.: Rauenthaler Baiken, a single vineyard). The village name (e.g.: Rauenthal") is normally identified by the possessive form "-er" suffix and is sometimes followed by the vineyard name ("Baiken").

- If the wine is estate-bottled (Erzeugerabfüllung or Gutsabfüllung), bottled by a co-op (Winzergenossenschaft), or by a third party bottler (Abfüller).

- Address of the winery

- The logo of the Association of German Prädikat Wine Estates (Verband Deutscher Prädikats- und Qualitätsweingüter, or more commonly VDP) which is awarded to the top 200 producers, as voted among themselves. The logo is a black eagle with a cluster of grapes in the center. The winery in the image example has the VDP logo. While not a guarantee, the presence of the VDP logo is a helpful insight into the quality of the wine.

Criticism

In recent years, the official classification has been criticised by many of the top producers, and additional classifications have been set down by wine growers' organisations such as VDP, without enjoying legal protection. The two main reasons for criticism are that the official classification does not differentiate between better and lesser vineyards and that the quality levels are less appropriate to high-quality dry wines.[15]

Germany emphasizes must weights because its climate makes it a challenge to ripen grapes fully, but many vintners believe that the classification system does not improve wine quality. Some producers choose to declassify themselves from one Prädikat to a lower one, or to Qualitätswein, because the wine does not reach their own personal evaluation of what constitutes a certain Prädikat.

Attempts were made in 1989 and 1993 to comply with EU regulations to limit yield, but little progress was made. Impatient with this, the prestigious VDP growers' association successfully instituted reasonably stringent limits for their members. The 1993 legislation successfully raised minimum must weights for Pradikats in several notable Anbaugebieten, and limited moves were made to clarify the labeling system.[16]

In the Mittelrhein, some producers have come together to establish the Mittelrhein Riesling Charta[17] for the introduction and promotion of three distinctive wines that each of its members can produce. These wines that have to fulfill superior quality standards are designed to be recognizable premium products that reflect the quality and diversity of its landscape and viticulture. Each of these wines is made of 100% Riesling and is classified into three categories: ‘Handstreich’, ‘Felsenspiel’ and ‘Meisterstück’. The categories are distinguished by their sensory features, their residual acidity-to-sugar-ratio, and the volume of alcohol.[18]

Notes

- ↑ Robinson, Jancis (2006). The Oxford Companion To Wine. Oxford University Press. p. 308. ISBN 0198609906.

- ↑ MacNeil, Karen (2001). The Wine Bible. New York: Workman Publishing. pp. 520–521. ISBN 9781563054341.

- ↑ Verordnung (EG) Nr. 479/2008 des Rates vom 29. April 2008 über die gemeinsame Marktorganisation für Wein chapter 27

- ↑ Deutsches Weininstitut: German Wine Statistics 2006-2007

- ↑ MacNeil, Karen (2001). The Wine Bible. New York: Workman Publishing. p. 521. ISBN 9781563054341.

- ↑ Deutsches Weininstitut (German Wine Institute): Must weights Archived April 14, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Deutsches Weininstitut: Sparkling wine (Sekt), accessed on March 25, 2009

- ↑ Deutsches Weininstitut: Weinarten

- ↑ Deutsches Weininstitut: Specialty & Regional wines

- ↑ Deutsches Weininstitut: Güteklassen

- ↑ Deutsches Weininstitut: Classic wines

- ↑ GmbH, Deutsches Weininstitut. "Selection wines". www.germanwines.de. Retrieved 2016-02-19.

- ↑ Wein-Plus Glossar, Cabinet

- ↑ Wein-Plus Glossar, Naturwein

- ↑ O. Bird, Rheingold - the German Wine Renaissance, Arima publishing, 2005, ISBN 1-84549-079-7

- ↑ Robinson, Jancis (2006). The Oxford Companion To Wine. Oxford University Press. p. 309. ISBN 0198609906.

- ↑ Mittelrhein Riesling Charta

- ↑ Classification of German Wines, MRC RomanticWine.de