George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon

| The Earl of Carnarvon | |

|---|---|

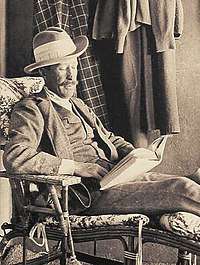

Lord Carnarvon, who was the chief financial backer on many of Howard Carter's Egyptian excavations. | |

| Born |

26 June 1866 Highclere Castle, Hampshire, England |

| Died |

5 April 1923 (aged 56) Cairo, Kingdom of Egypt |

| Nationality | British |

| Known for | Discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb |

George Edward Stanhope Molyneux Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon, DL (26 June 1866 – 5 April 1923), styled Lord Porchester until 1890, was an English peer and aristocrat best known as the financial backer of the search for and the excavation of Tutankhamun's tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

Background and education

Styled Lord Porchester from birth, he was born at the family seat, Highclere Castle, in Hampshire, the only son of Henry Herbert, 4th Earl of Carnarvon, a distinguished Tory statesman, by his first wife Lady Evelyn Stanhope, daughter of George Stanhope, 6th Earl of Chesterfield. Aubrey Herbert was his half-brother.[1] He was educated at Eton College and Trinity College, Cambridge.[2] He inherited the Bretby Hall estate in Derbyshire from his maternal grandmother, Anne Elizabeth, Dowager Countess of Chesterfield (1802-1885), and succeeded his father in the earldom in 1890.[3]

Family

Lord Carnarvon married Almina Victoria Maria Alexandra Wombwell,[4] illegitimate daughter of millionaire banker Alfred de Rothschild,[5] of the Rothschild family, at St. Margaret's Church, Westminster, on 26 June 1895. Rothschild provided a marriage settlement of £500,000 and paid off all Lord Carnarvon’s existing debts.[6] The Carnarvons had two children:[1]

- Henry George Herbert, 6th Earl of Carnarvon (7 November 1898 – 22 September 1987), who married Anne Catherine Tredick Wendell (d.1977) and had one son (the 7th Earl) and one daughter. They divorced in 1936 and from 1939 to 1947, he was married to actress and dancer Tilly Losch.

- Lady Evelyn Leonora Almina Herbert (15 August 1901 – 31 January 1980), who married Sir Brograve Beauchamp, 2nd Baronet and had a daughter.[7]

Horse racing

Exceedingly wealthy due to his marriage settlement,[6] Carnarvon was at first best known as an owner of racehorses and a reckless driver of early cars, suffering in 1901 a serious motoring accident near Bad Schwalbach in Germany, after which he never fully recovered his health.[8] In 1902, he established Highclere Stud to breed thoroughbred racehorses.[9] In 1905, he was appointed one of the Stewards at the new Newbury Racecourse. His family has maintained the connection ever since. His grandson, the 7th Earl, was racing manager to Queen Elizabeth II from 1969, and one of the Queen's closest friends.

Egyptology

Lord Carnarvon was an enthusiastic amateur Egyptologist, and Lord and Lady Carnarvon often spent their winters in Egypt, where they bought antiquities for their collection in England.[8]

In 1907 Lord Carnarvon undertook to sponsor the excavation of nobles' tombs in Deir el-Bahri, near Thebes. He employed Howard Carter to undertake the work,[11] on the recommendation of Gaston Maspero, Director of the Egyptian Antiquities Department.[12]

In 1914 Lord Carnarvon received the concession to dig in the Valley of the Kings, replacing Theodore Davis who had resigned, Carter again leading the work. Excavations were interrupted during the First World War, but resumed in late 1917.[8] By 1922 little of significance had been found and Lord Carnarvon decided this would be the final year he would fund the work.[13] However, on 4 November 1922, Carter was able to send a telegram to Lord Carnarvon, in England, saying:

"At last have made wonderful discovery in Valley; a magnificent tomb with seals intact; re-covered same for your arrival; congratulations".[8]

Although a semi-invalid due to injuries sustained in a serious automobile accident in 1903,[14] Lord Carnarvon, accompanied by his daughter Lady Evelyn Herbert, returned to Egypt. The tomb was to be officially opened under the supervision of the Egyptian Department of Antiquities on 29 November. However, on 26 and 27 November Carter, his assistant Arthur Challender, Lord Carnarvon and Lady Evelyn made several unauthorised visits inside the tomb[15] and were present when Carter made a tiny breach in the top left hand corner of the tomb's doorway. He was able to peer in by the light of a candle. Carnarvon asked, "Can you see anything?" Carter replied with the famous words: "Yes, wonderful things!"[16] They then entered the tomb,[17] becoming the first people in modern times to do so. Challender rigged up electric lighting, illuminating a jumble of items, including gilded couches, chests, thrones, and shrines. They also found two more sealed doorways, including one to the inner burial chamber,[15] guarded by two life-size statues of Tutankhamun. A small hole was found in this doorway and Carter, Carnarvon and Lady Evelyn crawled through it into the inner burial chamber.[8]

Lord Carnarvon travelled to England in December 1922, returning in January 1923 to be present at the official opening of the inner burial chamber on 16 February.[18] Towards the end of February a rift with Carter, probably caused by a disagreement on how to manage the supervising Egyptian authorities, temporarily closed excavation. Work recommenced in early March after Carnarvon apologised.[19] This was to be Lord Carnarvon's last significant involvement in the excavation project, he falling seriously ill shortly afterwards.

Death

On 19 March 1923, Carnarvon suffered a severe mosquito bite which became infected by a razor cut. On 5 April, he died in the Continental-Savoy Hotel in Cairo.[20] Fueled by author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's suggestion that Carnarvon's death had been caused by "elementals" created by Tutankhamun's priests to guard the royal tomb;[21] the "Curse of Tutankhamun," or, the "Mummy's Curse," entered popular culture. Arthur Weigall had reported, six weeks before his death, that he had watched Lord Carnarvon laughing and joking as he'd entered King Tut's tomb, and had remarked to nearby reporter H. V. Morton, "I give him six weeks to live."[22] A mystical writer working under the name Marie Corelli also declared in a letter published by the New York World magazine that she had warned the Earl (two weeks before his death) of the "dire punishment" likely to occur to those who rifle Egyptian tombs, claiming to cite an ancient book that indicated that poisons had been left after burials.[23][24]

A study of documents and scholarly sources led The Lancet to conclude as unlikely that Carnarvon's death had anything to do with Tutankhamun's tomb, refuting another theory that exposure to toxic fungi (mycotoxins) had contributed to his demise. Although he was one of the men to enter the tomb, on several occasions, none of the other 25 from Europe were affected in the months after the entries.[25] The cause of Carnarvon's death was reported as "'pneumonia supervening on [facial] erysipelas,' (a streptococcal infection of the skin and underlying soft tissue). Pneumonia was thought to be only one of various complications, arising from the progressively invasive infection, that eventually resulted in multiorgan failure."[26] The Earl had been "prone to frequent and severe lung infections" according to The Lancet and there had been a "general belief ... that one acute attack of bronchitis could have killed him. In such a debilitated state, the Earl's immune system was easily overwhelmed by erysipelas".[27]

Lady Almina Carnarvon removed Lord Carnarvon's remains to England,[28] where his tomb appropriately reflects his archaeological interest, nestled within an ancient hill fort overlooking his family seat at Beacon Hill, Burghclere, Hampshire.[29] Carnarvon was survived by his wife Almina, who subsequently remarried, and their two children.

After Lord Carnarvon's death, the Egyptian government took ownership of the artifacts in the East Valley of the Kings and in April 1930 provided a grant of £35,000 to his heirs.[30]

In popular culture

- Carnarvon has been portrayed several times in film, video game and television productions:[31]

- By Harry Andrews in the 1980 Columbia Pictures Television production The Curse of King Tut's Tomb.

- By Julian Curry in the 1998 IMAX documentary Mysteries of Egypt.

- By Julian Wadham in the 2005 BBC docudrama Egypt.

- By Sam Neill in the 2016 ITV series Tutankhamun.

- In the film The Mummy the character Evelyn Carnahan is named in tribute to Lord Carnarvon's daughter Lady Evelyn[32] whose father, although not named, is described as one of Egyptology's "finest patrons".

- 'Lord Carnarvon' is the quest leader for the Archaeologist role in the classic text-based video game Nethack.

- His country house, Highclere Castle, serves as the filming location of the ITV/PBS television series Downton Abbey, except that the below-stairs scenes were filmed on a set in London, as Highclere's basement is the home of Carnarvon's Egyptian collections. Highclere is owned by the present earl.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Works

- Earl of Carnarvon; et al. (1912). Five years' explorations at Thebes: a record of work done 1907-1911. London: Henry Frowde.

References

- 1 2 thepeerage.com George Edward Stanhope Molyneux Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon

- ↑ "Herbert, George Edward Stanhope Molyneux, Lord Porchester (HRBT886GE)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ Zoehfeld, Kathleen Weidner; Nelson, James (2007). "3". The Curse of King Tut's Mummy. Random House Books for Young Readers. ISBN 978-0-375-83862-0.

- ↑ Barnard Burke, 1914, p.387

- ↑ Seymour, Miranda (15 September 2011). "Lady Almina and the Real Downton Abbey by Fiona Carnarvon – review". The Guardian.

- 1 2 William Cross. Carnarvon, Carter and Tutankhamun Revisited: The Hidden Truths and Doomed Relationships. p. 31 Published by author. 2016. ISBN 9781905914364.

- 1 2 Charles Mosley, editor, Burke's Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage, 107th edition, 3 volumes (Wilmington, Delaware, U.S.A.: Burke's Peerage (Genealogical Books) Ltd, 2003).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bill Price. Tutankhamun, Egypt's Most Famous Pharaoh. pp. 119-128. Published Pocket Essentials, Hertfordshire. 2007. ISBN 9781842432402.

- ↑ "Architecture". House and Garden. Condé Nast Publications, Ltd. 160 (1–4): 54. 1994.

- ↑ Harry Burton’s photos of Tutankhamun’s Tomb, Griffith Institute Archive.

- ↑ Winstone, H. V. F. (2006). Howard Carter and the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun (rev. ed.). Manchester: Barzan. ISBN 1-905521-04-9.

- ↑ A letter of Maspero dated 14 October 1907, in his archives in the library of the Institut de France says: You have been kind enough to say to me that you could find a man who knows Egyptology to survey my works. Have you thought to anybody? I will leave the question of payment in your hands but I think I would prefer a compatriot (Manuscripts 4009, folios 292-293). On 16 January 1909, Carter writes to Maspero: Just a word to tell you that Lord Carnarvon has accepted my conditions. He will be there (in Egypt) from 12 February to 20 March. I have to thank you again... (Manuscripts 4009, folio 527) - from Elisabeth David.

- ↑ Carnarvon, Fiona (2011). Highclere Castle. Highclere Enterprises. p. 59.

- ↑ "The death of Lord Carnarvon".

- 1 2 "Howard Carter's diary entry for 25-27 November 1922".

- ↑ Lord Carnarvon's description, 10 December 1922, quoted in: Reeves, Nicholas; Taylor, John H. (1992). Howard Carter before Tutankhamun. London: British Museum. p. 141. ISBN 0-7141-0952-5.

- ↑ Reeves, C. N. (1990). Valley of the Kings: the decline of a royal necropolis. London: Kegan Paul. p. 63. ISBN 0-7103-0368-8.

- ↑ "Howard Carter's diary entry for 16 February 1923".

- ↑ Bill Price. Tutankhamun, Egypt's Most Famous Pharaoh. p. 130-131. Published Pocket Essentials, Hertfordshire. 2007. ISBN 9781842432402.

- ↑ "Carnarvon Is Dead Of An Insect's Bite At Pharaoh's Tomb. Blood poisoning and ensuing pneumonia conquer Tutankhamun discoverer in Egypt". New York Times. 5 April 1923. Retrieved 12 August 2008.

The Earl of Carnarvon died peacefully at 2 o'clock this morning. He was conscious almost to the end.

- ↑ Hamilton-Paterson, J Mummies: Death and Life in Ancient Egypt, James Hamilton-Paterson, Carol Andrews, p. 197, Collins for British Museum Publications, 1978, p. 196. ISBN 0-00-195532-2

- ↑ Winstone, H.V.F. Howard Carter and the Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun, H. V. F. Winstone, Constable, 1991, p. 262. ISBN 0-09-469900-3

- ↑ The Shadow King: The Bizarre Afterlife of King Tut's Mummy, Jo Marchant, 2013, chapter 4. ISBN|10:0306821338

- ↑ [Ancient Egypt, David P. Silverman, p. 146, Oxford University Press US, 2003, ISBN 0-19-521952-X]

- ↑ "The death of Lord Carnarvon".

- ↑ Cox, A. M. "The death of Lord Carnarvon", by Ann M. Cox; The Lancet; 7 June 2003. [sic]

- ↑ "The death of Lord Carnarvon".

- ↑ "Howard Carter's diary entry for 14 April 1923".

- ↑ Carnarvon's Tomb

- ↑ {{cite web|title=Egyptologist Howard Carter dies - archive, 1939|url=https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2018/mar/05/egyptologist-howard-carter-dies-archive-1939.

- ↑ "Carnarvon (Character)". IMDb.com. Archived from the original on 2013-10-09. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

- ↑ "Radio Times.com 23 Nov 2016 Did Howard Carter and Evelyn Carnarvon have a romantic relationship?". Retrieved 14 January 2018.

Further reading

- with Howard Carter, Five Years' Explorations at Thebes - A Record of Work Done 1907-1911, ed. Paul Kegan, 2004 ( ISBN 0-7103-0835-3).

- Five Years' Explorations at Thebes

- Fiona Carnarvon, Egypt at Highclere - The discovery of Tutankhamun, Highclere Enterprises LPP, 2009.

- Fiona Carnarvon, Carnarvon & Carter - the story of the two Englishman who discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun, Highclere Enterprises LPP, 2007.

- Elisabeth David, Gaston Maspero 1846-1916, Pygmalion/Gérard Watelet, 1999 ( ISBN 2-85704-565-4).

- Cross William, Carnarvon, Carter and Tutankhamun Revisited. The hidden truths and doomed relationships, Book Midden Publishing, 2016 ( ISBN 978-1905914-36-4).

- Cross William, Lordy! Tutankhamun's Patron As A Young Man , Book Midden Publishing, 2012 ( ISBN 978-1-905914-05-0).

- Cross William, The Life and Secrets of Almina Carnarvon : 5th Countess of Carnarvon of Tutankhamun Fame , 3rd Ed 2011 ( ISBN 978-1-905914-08-1).

- Cross William, Catherine and Tilly: Porchey Carnarvon's Two Duped Wives: The Tragic Tales of the Sixth Countesses of Carnarvon, Book Midden Publishing, 2013 ( ISBN 978-1905914-25-8).

External links

- Works by Carnarvon at Project Gutenberg

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Earl of Carnarvon

- George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon Bio at Highclere Castle

- Highclere Castle, home of the 5th Earl

- Newspaper clippings about George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon in the 20th Century Press Archives of the German National Library of Economics (ZBW)

| Peerage of Great Britain | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Henry Herbert |

Earl of Carnarvon 1890–1923 |

Succeeded by Henry Herbert |