Garamantes

The Garamantes are a tribe mentioned by Herodotus. They are thought to correspond to Iron Age Berber tribes in the southwest of ancient Libya.

These tribes constituted a local power between roughly 500 BC and 700 AD. They used an underground irrigation system, and founded a number of kingdoms or city-states in the Fezzan area of Libya, in the Sahara desert. There is little textual information about them, their epigraphy being "...a still nearly indecipherable proto-Tifaniq, the script of modern-day Tuaregs."[1] Another important source of information is the abundant rock art of the region, which often depicts life prior to the rise of the tribal chiefdoms.

History

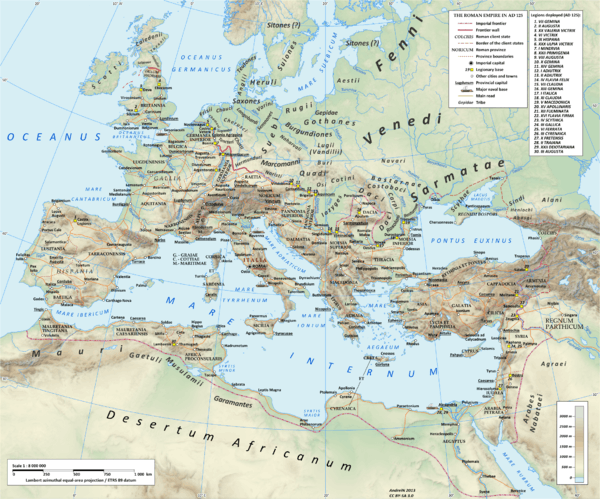

The Garamantes were probably present as tribal people in the Fezzan by 1000 BC. They appear in the written record for the first time in the 5th century BC: according to Herodotus, they were "a very great nation" who herded cattle, farmed dates, and hunted the Troglodytae ("cave-dwellers") who lived in the desert, from four-horse chariots.[2] Roman depictions describe them as bearing ritual scars and tattoos. Tacitus wrote that they assisted the rebel Tacfarinas and raided Roman coastal settlements. According to Pliny the Elder, Romans eventually grew tired of Garamantian raiding and Lucius Cornelius Balbus captured 15 of their settlements in 19 BC. In 202, Septimius Severus captured the capital city of Garama.[3]

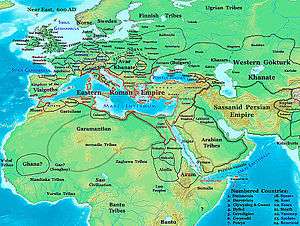

By around 150 AD the Garamantian kingdom (in today's central Libya (Fezzan), principally along the still existing Wadi al-Ajal), covered 180,000 square kilometres in modern-day southern Libya. It lasted from about 400 BC to 600 AD.

The decline of the Garamantian culture may have been connected to worsening climatic conditions, or overuse of water resources.[4] What is desert today was once fairly good agricultural land and was enhanced through the Garamantian irrigation system 1,500 years ago. As fossil water is a non-renewable resource, over the six centuries of the Garamantian kingdom, the ground water level fell.[5] The kingdom declined and fragmented.

Society

In the 1960s, archaeologists excavated part of the Garamantes' capital at modern Germa (situated around 150 km west of modern-day Sabha) and named it Garama (an earlier capital, Zinchecra, was located not far from the later Garama). Current research indicates that the Garamantes had about eight major towns, three of which have been examined as of 2004. In addition they had a large number of other settlements. Garama had a population of around four thousand and another six thousand living in villages within a 5 km radius.

The Garamantes were farmers and merchants. Their diet consisted of grapes, figs, barley, and wheat. They traded wheat, salt and slaves in exchange for imported wine and olive oil, oil lamps and Roman tableware. According to Strabo and Pliny, the Garamantes quarried amazonite in the Tibesti Mountains. In 2011, Efthymia Nikita reported that Garamantes skeletons do not suggest regular warfare or strenuous activities. "The Garamantes exhibited low sexual dimorphism in the upper limbs, which is consistent to the pattern found in agricultural populations and implies that the engagement of males in warfare and construction works was not particularly intense. [...] the Garamantes did not appear systematically more robust than other North African populations occupying less harsh environments, indicating that life in the Sahara did not require particularly strenuous daily activities."[6]

Archaeological remains

Archaeological ruins associated with the Garamantian kingdom include numerous tombs, forts, and cemeteries. The Garamantes constructed a network of underground tunnels, and shafts to mine the fossil water from under the limestone layer under the desert sand. The dating of these foggara is disputed, they appear between 200 BC to 200 AD but continued to be in use until at least the 7th century and perhaps later.[7] The network of tunnels is known to Berbers as Foggaras. The network allowed agriculture to flourish, and used a system of slave labor to keep it maintained.

References

- ↑ Werner, Louis. "Libya's Forgotten Desert Kingdom". saudiaramcoworld.com. Saudi Aramco World. Retrieved August 15, 2016.

May/June 2004; Volume 55, Number 3

- ↑

- ↑ Birley (1999), p. 153.

- ↑ Fall of Gaddafi opens a new era for the Sahara's lost civilisation, Guardian, retrieved 5/11/2011

- ↑ Fentress and Wilson (2016)

- ↑ Nikita, Efthymia (2011). "Activity patterns in the Sahara Desert: An interpretation based on cross-sectional geometric properties". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 146: 423–434. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21597.

- ↑ David Mattingly (ed.). 2003. Archaeology of Fazzan. Volume 1, Synthesis. London

Bibliography

- Birley, Anthony R. (1999) [1971]. Septimius Severus: The African Emperor. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16591-1.

- N. Barley (Review). Reviewed work(s): Les chars rupestres sahariens: des syrtes au Niger, par le pays des Garamantes et des Atlantes by Henri Lhote Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 48, No. 1 (1985), pp. 210–210

- E.Fentress and A. Wilson: 'The Saharan Berber diaspora and the southern frontiers of Vandal and Byzantine North Africa', in J. Conant and S. Stevens (eds),North Africa under Byzantium and Early Islam, ca. 500 – ca. 800 (Dumbarton Oaks Byzantine Symposia and Colloquia. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection). 41-63.

Further reading

- Timothy F. Garrard. Myth and Metrology: The Early Trans-Saharan Gold Trade The Journal of African History, Vol. 23, No. 4 (1982), pp. 443–461

- Ulrich Haarmann. The Dead Ostrich Life and Trade in Ghadames (Libya) in the Nineteenth Century. Die Welt des Islams, New Series, Vol. 38, Issue 1 (March 1998), pp. 9–94

- R. C. C. Law . The Garamantes and Trans-Saharan Enterprise in Classical Times The Journal of African History, Vol. 8, No. 2 (1967), pp. 181–200

- Daniel F. McCall. Herodotus on the Garamantes: A Problem in Protohistory History in Africa, Vol. 26, (1999), pp. 197–217

- Count Byron Khun de Prorok. Ancient Trade Routes from Carthage into the Sahara Geographical Review, Vol. 15, No. 2 (April 1925), pp. 190–205

- Brent D. Shaw. Climate, Environment and Prehistory in the Sahara. World Archaeology, Vol. 8, No. 2, Climatic Change (October 1976), pp. 133–149

- Richard Smith. What Happened to the Ancient Libyans? Chasing Sources across the Sahara from Herodotus to Ibn Khaldun. Journal of World History - Volume 14, Number 4, December 2003, pp. 459–500

- John T. Swanson. The Myth of Trans-Saharan Trade during the Roman Era The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 8, No. 4 (1975), pp. 582–600

- Belmonte, Juan Antonio; Esteban, César; Perera Betancort, Maria Antonia; Marrero, Rita. Archaeoastronomy in the Sahara: The Tombs of the Garamantes at Wadi el Agial, Fezzan, Libya. Journal for the History of Astronomy Supplement, Vol. 33, 2002

- Raymond A. Dart . The Garamantes of central Sahara. African Studies, Volume 11, Issue 1 March 1952, pages 29 – 34

- Bryn Mawr Classical Review of David. J. Mattingly (ed.), The Archaeology of Fazzan. Volume 2. Site Gazetteer, Pottery and Other Survey Finds. Society for Libyan Studies Monograph 7. London: The Society for Libyan Studies and Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahariya Department of Antiquities, 2007. Pp. xxix, 522, figs. 760, tables 37. ISBN 1-900971-05-4.

- Karim Sadr (Reviewer): WHO WERE THE GARAMANTES AND WHAT BECAME OF THEM? The Archaeology of Fazzan. Volume I: Synthesis. Edited by DAVID J. MATTINGLY. London: Society for Libyan Studies, and Tripoli: Department of Antiquities, 2003. ( ISBN 1-90097-102-X) Review in The Journal of African History (2004), 45: 492-493

- Victor Paul Borg. The Garamantes masters of the Sahara. Geographical, Vol. 79, August 2007.

- Gabriel Camps. Les Garamantes, conducteurs de chars et bâtisseurs dans le Fezzan antique. Clio.fr (2002).

- Kevin White, David Mattingly. Ancient lakes of the Sahara. American Scientist. January–February 2006.

- Théodore Monod, L’émeraude des Garamantes, Souvenirs d’un Saharien. Paris: L’Harmattan. (1984).

- Eamonn Gearon. The Sahara: A Cultural History. Signal Books, UK, 2011. Oxford University Press, USA, 2011.

External links

- The Royal Saharan Kingdom Garamantes Civilization

- "Kingdom of the Sands"

- Encyclopaedia of the Orient - article about Garamantian empire

- romansonline.com: Classical Latin texts citing the Garamantes.

- LiveScience.com article - about "lost cities" built by the Garamantes in Libya, most dating between AD 1 to 500, 7 November 2011