Funicular

.jpg)

A funicular (/fəˈnɪkjʊlər/) is one of the modes of transportation which uses a cable traction for movement on steep inclined slopes.[1]

A funicular railway employs a pair of passenger vehicles which are pulled on a slope by the same cable which loops over a pulley wheel at the upper end of a track. The vehicles are permanently attached to the ends of the cable and counterbalance each other. They move synchronously: while one vehicle is ascending the other one is descending the track. These particularities distinguish funiculars from other types of cable railways. For example, a funicular is distinguished from an inclined elevator by the presence of two vehicles which counterbalance each other.[2][1][3]

The name "funicular" itself is derived from the Latin word funiculus, the diminutive of funis, which translates as "rope".[4]

Operation

The basic idea of funicular operation is that two cars are always attached to each other by a cable, which runs through a pulley at the top of the slope. Counterbalancing of the two cars, with one going up and one going down, minimizes the energy needed to lift the car going up. Winching is normally done by an electric drive that turns the pulley. Sheave wheels guide the cable to and from the drive mechanism and the slope cars.

Track layout

.jpg)

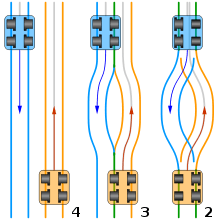

Early funiculars used two parallel straight tracks, four rails, with separate station platforms for each vehicle. The tracks are laid with sufficient space between them for the two cars to pass at the midpoint. Three-rail arrangement was also used to overcome the half-way passing problem.[1]

The wheels of the cars are usually single-flanged, as on standard railway vehicles. Examples of this type of track layout are the Duquesne Incline in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and most cliff railways in the UK.

The Swiss engineer Carl Roman Abt invented the method that allows cars to be used with a two-rail configuration: the outboard wheels have flanges on both sides, which keeps them aligned with the outer rail, thus holding each car in position, whereas the inboard wheels are unflanged and ride on top of the opposite rail, thereby easily crossing over the rails (and cable) at the passing track.[1]

Two-rail configurations of this type avoid the need for switches and crossings, since the cars have the flanged wheels on opposite sides and will automatically follow different tracks, and in general, significantly reduce costs.

In layouts using three rails, the middle rail is shared by both cars. The three-rail layout is wider than the two-rail layout, but the passing section is simpler to build. If a rack for braking is used, that rack can be mounted higher in a three-rail layout, making it less sensitive to choking in snowy conditions.[5]

Some four-rail funiculars have the upper and lower sections interlaced and a single platform at each station. The Hill Train at Legoland, Windsor, is an example of this configuration.

The track layout can also be changed during the renovation of a funicular, and often four-rail layouts have been rebuilt as two- or three-rail layouts; e.g., the Wellington Cable Car in New Zealand was rebuilt with two rails.

Bottom towrope

The cars can be attached to a second cable running through a pulley at the bottom of the incline in case the gravity force acting on the vehicles is too low to operate them on the slope. One of the pulleys must be designed as a tensioning wheel to avoid slack in the ropes. In this case, the winching can also be done at the lower end of the incline. This practice is used for funiculars with gradients below 6%, funiculars using sledges instead of cars, or any other case where it is not ensured that the descending car is always able to pull out the cable from the pulley in the station on the top of the incline.[5] Another reason for a bottom cable is that the cable supporting the lower car at the extent of its travel will potentially weigh several tons, whereas that supporting the upper car weighs virtually nothing. The lower cable adds an equal amount of cable weight to the upper car while deducting the same weight from the lower, thereby keeping the cars in equilibrium.

Water counterbalancing

A few funiculars have been built using water tanks under the floor of each car that are filled or emptied until just sufficient imbalance is achieved to allow movement. The car at the top of the hill is loaded with water until it is heavier than the car at the bottom, causing it to descend the hill and pulling up the other car. The water is drained at the bottom, and the process repeats with the cars exchanging roles. The movement is controlled by a brakeman.

The Giessbachbahn in the Swiss canton of Berne, opened in 1879, originally was powered by water ballast. Later on it was converted to electrical power. The Bom Jesus funicular built in 1882 near Braga, Portugal is another example.

The funicular Neuveville - St-Pierre in Fribourg, Switzerland,[6] is of a particular interest as for counterbalancing it utilizes waste water, coming from a sewage plant at the upper part of the city.[7]

History

Funicular railways operating in urban areas date from the 1860s. The first line of the Funiculars of Lyon (Funiculaires de Lyon) opened in 1862, followed by other lines in 1878, 1891 and 1900. The Budapest Castle Hill Funicular was built in 1868–69, with the first test run on 23 October 1869. In Istanbul, Turkey, the Tünel has been in continuous operation since 1875 and is both the first underground funicular and the second-oldest underground railway. The oldest funicular railway operating in Britain dates from 1875 and is in Scarborough, North Yorkshire.[8]

Until the end of the 1870s, the four-rail parallel-track funicular was the normal configuration. Carl Roman Abt developed the Abt Switch allowing the two-rail layout, which was used for the first time in 1879 when the Giessbach Funicular opened in Switzerland.[5]

In the United States, the first funicular to use a two-rail layout was the Telegraph Hill Railroad in San Francisco, which was in operation from 1884 until 1886.[9] The Mount Lowe Railway in Altadena, California, was the first mountain railway in the United States to use the three-rail layout. Three- and two-rail layouts considerably reduced the space required for building a funicular, reducing grading costs on mountain slopes and property costs for urban funiculars. These layouts enabled a funicular boom in the latter half of the 19th century.

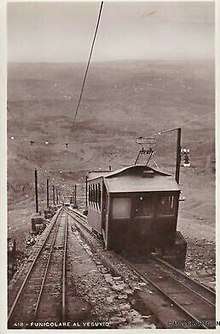

In 1880 the funicular of Mount Vesuvius inspired the song Funiculì, Funiculà, composed by Luigi Denza and lyrics by Peppino Turco. Unfortunately, this funicular was wrecked repeatedly by volcanic eruptions and abandoned after the eruption of 1944.

Inclined elevator

An inclined elevator is not a funicular since it has only one car carrying payload on the slope.[2]

For example, despite its name the Montmartre Funicular in Paris after a reconstruction in 1991 is technically a double inclined elevator[10] since each of its two cabins have its own cable traction with own counterweight and they operate independently from each other.[11]

Remarkable examples

According to the Guinness World Records the smallest public funicular in the world is the Fisherman's Walk Cliff Railway in Bournemouth, England with its length of 39 metres (128 ft).[12][13]

Stoosbahn in Switzerland with its maximum gradient of 110% is the steepest funicular in the world.[14]

Valparaiso in Chile, used to have up to 30 funicular elevators (Spanish: ascensores), the oldest dating from 1883. Only 15 of them have remained in the city. Nearly half of them are in operation, although the authorities are making some efforts to restore the others remained into a working condition.

The Carmelit in Haifa, Israel, with its 6 stations and a tunnel 1.8 km (1.1 mi) long is claimed by the Guinness World Records as the "least extensive metro" in the world. The Carmelit itself is never claimed to be a metro system.[15] Technically it is an underground funicular.

The Dresden Schwebebahn is the only suspended funicular in the world, hanging from an elevated rail.[16]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 The Giessbach Funicular with the World’s First Abt Switch (PDF). The American Society of Mechanical Engineers. 2015.

- 1 2 Kittelson & Assoc, Inc., Parsons Brinckerhoff, Inc., KFH Group, Inc., Texam A&M Transportation Institute, & Arup (2013). "Chapter 11: Glossary and Symbols". Transit Capacity and Quality of Service Manual. Transit Cooperative Highway Research Program (TCRP) Report 165 (Third ed.). Washington: Transportation Research Board. p. 11-20.

- ↑ Pyrgidis, Christos N. (2016-01-04). "Cable railway systems for steep gradients". Railway Transportation Systems: Design, Construction and Operation. CRC Press. p. 251-259. ISBN 978-1-4822-6215-5.

- ↑ "funicular". Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved 2018-07-03.

- 1 2 3 Walter Hefti: Schienenseilbahnen in aller Welt. Schiefe Seilebenen, Standseilbahnen, Kabelbahnen. Birkhäuser, Basel 1975, ISBN 3-7643-0726-9 (German)

- ↑ "Funiculaire Neuveville - St-Pierre". Transports publics fribourgeois Holding (TPF) SA.

- ↑ Kirk, Mimi (16 June 2016). "A Lasting Stink: Fribourg's Sewage-Powered Funicular". The Atlantic. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ "Blunder traps eight on cliff lift". BBC News. 24 April 2009. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ "Telegraph Hill Railroad". The Cable Car Home Page – Cable Car Lines in San Francisco. Joe Thompson. 1 July 2009. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

The Telegraph Hill Railroad was not a cable car line ...; it was a funicular railway

- ↑ "7 Line Extension Inclined Elevators" (PDF). MTA Capital Construction. April 28, 2014. Retrieved 2018-06-20.

- ↑ Pyrgidis, Christos N. (2016-01-04). "Cable railway systems for steep gradients". Railway Transportation Systems: Design, Construction and Operation. CRC Press. p. 260. ISBN 978-1-4822-6215-5.

- ↑ Guinness World Records 2015. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-908843-63-0.

- ↑ News, Caroline Lowbridge BBC. "Ten Bournemouth facts football fans might not know". BBC News. Retrieved 2016-01-04.

- ↑ Willsher, Kim (2017-12-15). "World's steepest funicular rail line to open in Switzerland". The Guardian. Retrieved 2017-12-16.

- ↑ "Carmelit Haifa – The most convenient way to get around the city". Carmelit. Retrieved 2018-07-04.

- ↑ "Schwebebahn - DVB | Dresdner Verkehrsbetriebe AG". www.dvb.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-07-05.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Funiculars. |

- Funimag, the first web magazine about funiculars