Fullerene

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Nanomaterials |

|---|

|

| Carbon nanotubes |

| Fullerenes |

| Other nanoparticles |

| Nanostructured materials |

|

A fullerene is an allotrope of carbon in the form of a hollow sphere, ellipsoid, tube, and many other shapes. Spherical fullerenes, also referred to as Buckminsterfullerenes or buckyballs, resemble the balls used in association football. Cylindrical fullerenes are also called carbon nanotubes (buckytubes). Fullerenes are similar in structure to graphite, which is composed of stacked graphene sheets of linked hexagonal rings. Unless they are cylindrical, they must also contain pentagonal (or sometimes heptagonal) rings.[1]

The first fullerene molecule to be discovered, and the family's namesake, buckminsterfullerene (C60), was manufactured in 1985 by Richard Smalley, Robert Curl, James Heath, Sean O'Brien, and Harold Kroto at Rice University. The name was an homage to Buckminster Fuller, whose geodesic domes it resembles. The structure was also identified some five years earlier by Sumio Iijima, from an electron microscope image, where it formed the core of a "bucky onion".[2] Fullerenes have since been found to occur in nature.[3] More recently, fullerenes have been detected in outer space.[4] According to astronomer Letizia Stanghellini, "It’s possible that buckyballs from outer space provided seeds for life on Earth."[5]

The discovery of fullerenes greatly expanded the number of known carbon allotropes, which had previously been limited to graphite, graphene, diamond, and amorphous carbon such as soot and charcoal. Buckyballs and buckytubes have been the subject of intense research, both for their chemistry and for their technological applications, especially in materials science, electronics, and nanotechnology.[6]

History

The icosahedral C60H60 cage was mentioned in 1965 as a possible topological structure.[7] Eiji Osawa of Toyohashi University of Technology predicted the existence of C60 in 1970.[8][9] He noticed that the structure of a corannulene molecule was a subset of an association football shape, and he hypothesised that a full ball shape could also exist. Japanese scientific journals reported his idea, but neither it nor any translations of it reached Europe or the Americas.

Also in 1970, R. W. Henson (then of the Atomic Energy Research Establishment) proposed the structure and made a model of C60. Unfortunately, the evidence for this new form of carbon was very weak and was not accepted, even by his colleagues. The results were never published but were acknowledged in Carbon in 1999.[10][11]

In 1973, independently from Henson, a group of scientists from the USSR made a quantum-chemical analysis of the stability of C60 and calculated its electronic structure. As in the previous cases, the scientific community did not accept the theoretical prediction. The paper was published in 1973 in Proceedings of the USSR Academy of Sciences (in Russian).[12]

In mass spectrometry discrete peaks appeared corresponding to molecules with the exact mass of sixty or seventy or more carbon atoms. In 1985 Harold Kroto of the University of Sussex, James R. Heath, Sean O'Brien, Robert Curl and Richard Smalley from Rice University, discovered C60, and shortly thereafter came to discover the fullerenes.[13] Kroto, Curl, and Smalley were awarded the 1996 Nobel Prize in Chemistry[14] for their roles in the discovery of this class of molecules. C60 and other fullerenes were later noticed occurring outside the laboratory (for example, in normal candle-soot). By 1990 it was relatively easy to produce gram-sized samples of fullerene powder using the techniques of Donald Huffman, Wolfgang Krätschmer, Lowell D. Lamb, and Konstantinos Fostiropoulos. Fullerene purification remains a challenge to chemists and to a large extent determines fullerene prices. So-called endohedral fullerenes have ions or small molecules incorporated inside the cage atoms. Fullerene is an unusual reactant in many organic reactions such as the Bingel reaction discovered in 1993. Carbon nanotubes were first discovered and synthesized in 1991.[15][16]

Minute quantities of the fullerenes, in the form of C60, C70, C76, C82 and C84 molecules, are produced in nature, hidden in soot and formed by lightning discharges in the atmosphere.[17] In 1992, fullerenes were found in a family of minerals known as Shungites in Karelia, Russia.[3]

In 2010, fullerenes (C60) have been discovered in a cloud of cosmic dust surrounding a distant star 6500 light years away. Using NASA's Spitzer infrared telescope the scientists spotted the molecules' unmistakable infrared signature. Sir Harry Kroto, who shared the 1996 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of buckyballs commented: "This most exciting breakthrough provides convincing evidence that the buckyball has, as I long suspected, existed since time immemorial in the dark recesses of our galaxy."[18]

Naming

The discoverers of the Buckminsterfullerene (C60) allotrope of carbon named it after Richard Buckminster Fuller, a noted architectural modeler who popularized the geodesic dome. Since buckminsterfullerenes have a similar shape to those of such domes, they thought the name appropriate.[19]

As the discovery of the fullerene family came after buckminsterfullerene, the shortened name 'fullerene' is used to refer to the family of fullerenes. The suffix "-ene" indicates that each C atom is covalently bonded to three others (instead of the maximum of four), a situation that classically would correspond to the existence of bonds involving two pairs of electrons ("double bonds").

Types of fullerene

Since the discovery of fullerenes in 1985, structural variations on fullerenes have evolved well beyond the individual clusters themselves. Examples include:[20]

- Buckyball clusters: smallest member is C

20 (unsaturated version of dodecahedrane) and the most common is C

60 - Nanotubes: hollow tubes of very small dimensions, having single or multiple walls; potential applications in electronics industry

- Megatubes: larger in diameter than nanotubes and prepared with walls of different thickness; potentially used for the transport of a variety of molecules of different sizes[21]

- polymers: chain, two-dimensional and three-dimensional polymers are formed under high-pressure high-temperature conditions; single-strand polymers are formed using the Atom Transfer Radical Addition Polymerization (ATRAP) route[22]

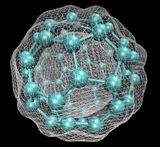

- nano"onions": spherical particles based on multiple carbon layers surrounding a buckyball core[23] proposed for lubricants;[24]

- linked "ball-and-chain" dimers: two buckyballs linked by a carbon chain[25]

- fullerene rings[26]

Buckyballs

Buckminsterfullerene

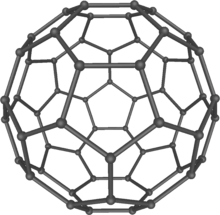

Buckminsterfullerene is the smallest fullerene molecule containing pentagonal and hexagonal rings in which no two pentagons share an edge (which can be destabilizing, as in pentalene). It is also most common in terms of natural occurrence, as it can often be found in soot.

The structure of C60 is a truncated icosahedron, which resembles an association football ball of the type made of twenty hexagons and twelve pentagons, with a carbon atom at the vertices of each polygon and a bond along each polygon edge.

The van der Waals diameter of a C60 molecule is about 1.1 nanometers (nm).[27] The nucleus to nucleus diameter of a C60 molecule is about 0.71 nm.

The C60 molecule has two bond lengths. The 6:6 ring bonds (between two hexagons) can be considered "double bonds" and are shorter than the 6:5 bonds (between a hexagon and a pentagon). Its average bond length is 1.4 angstroms.

Silicon buckyballs have been created around metal ions.

Boron buckyball

A type of buckyball which uses boron atoms, instead of the usual carbon, was predicted and described in 2007. The B80 structure, with each atom forming 5 or 6 bonds, is predicted to be more stable than the C60 buckyball.[28] One reason for this given by the researchers is that B80 is actually more like the original geodesic dome structure popularized by Buckminster Fuller, which uses triangles rather than hexagons. However, this work has been subject to much criticism by quantum chemists[29][30] as it was concluded that the predicted Ih symmetric structure was vibrationally unstable and the resulting cage undergoes a spontaneous symmetry break, yielding a puckered cage with rare Th symmetry (symmetry of a volleyball).[29] The number of six-member rings in this molecule is 20 and number of five-member rings is 12. There is an additional atom in the center of each six-member ring, bonded to each atom surrounding it. By employing a systematic global search algorithm, later it was found that the previously proposed B80 fullerene is not global minimum for 80 atom boron clusters and hence can not be found in nature.[31] In the same paper by Sandip De et al., it was concluded that boron's energy landscape is significantly different from other fullerenes already found in nature hence pure boron fullerenes are unlikely to exist in nature.

Other buckyballs

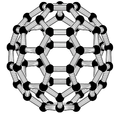

Another fairly common fullerene is C70,[32] but fullerenes with 72, 76, 84 and even up to 100 carbon atoms are commonly obtained.

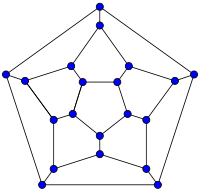

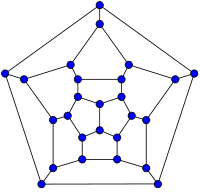

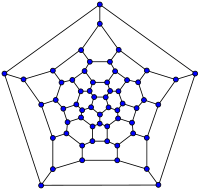

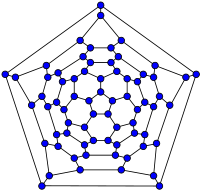

In mathematical terms, the structure of a fullerene is a trivalent convex polyhedron with pentagonal and hexagonal faces. In graph theory, the term fullerene refers to any 3-regular, planar graph with all faces of size 5 or 6 (including the external face). It follows from Euler's polyhedron formula, V − E + F = 2 (where V, E, F are the numbers of vertices, edges, and faces), that there are exactly 12 pentagons in a fullerene and V/2 − 10 hexagons.

|

|

|

|

| 20-fullerene (dodecahedral graph) |

26-fullerene graph | 60-fullerene (truncated icosahedral graph) |

70-fullerene graph |

The smallest fullerene is the dodecahedral C20. There are no fullerenes with 22 vertices.[33] The number of fullerenes C2n grows with increasing n = 12, 13, 14, ..., roughly in proportion to n9 (sequence A007894 in the OEIS). For instance, there are 1812 non-isomorphic fullerenes C60. Note that only one form of C60, the buckminsterfullerene alias truncated icosahedron, has no pair of adjacent pentagons (the smallest such fullerene). To further illustrate the growth, there are 214,127,713 non-isomorphic fullerenes C200, 15,655,672 of which have no adjacent pentagons. Optimized structures of many fullerene isomers are published and listed on the web.[34]

Heterofullerenes have heteroatoms substituting carbons in cage or tube-shaped structures. They were discovered in 1993[35] and greatly expand the overall fullerene class of compounds. Notable examples include boron, nitrogen (azafullerene), oxygen, and phosphorus derivatives.

Trimetasphere carbon nanomaterials were discovered by researchers at Virginia Tech and licensed exclusively to Luna Innovations. This class of novel molecules comprises 80 carbon atoms (C

80) forming a sphere which encloses a complex of three metal atoms and one nitrogen atom. These fullerenes encapsulate metals which puts them in the subset referred to as metallofullerenes. Trimetaspheres have the potential for use in diagnostics (as safe imaging agents), therapeutics[36] and in organic solar cells.[37]

Carbon nanotubes

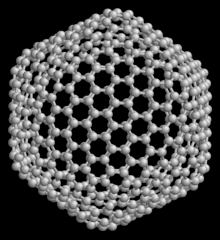

Nanotubes are cylindrical fullerenes. These tubes of carbon are usually only a few nanometres wide, but they can range from less than a micrometer to several millimeters in length. They often have closed ends, but can be open-ended as well. There are also cases in which the tube reduces in diameter before closing off. Their unique molecular structure results in extraordinary macroscopic properties, including high tensile strength, high electrical conductivity, high ductility, high heat conductivity, and relative chemical inactivity (as it is cylindrical and "planar" — that is, it has no "exposed" atoms that can be easily displaced). One proposed use of carbon nanotubes is in paper batteries, developed in 2007 by researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.[38] Another highly speculative proposed use in the field of space technologies is to produce high-tensile carbon cables required by a space elevator.

Carbon nanobuds

Nanobuds have been obtained by adding buckminsterfullerenes to carbon nanotubes.

Fullerite

Fullerites are the solid-state manifestation of fullerenes and related compounds and materials.

"Ultrahard fullerite" is a coined term frequently used to describe material produced by high-pressure high-temperature (HPHT) processing of fullerite. Such treatment converts fullerite into a nanocrystalline form of diamond which has been reported to exhibit remarkable mechanical properties.[39]

Inorganic fullerenes

Materials with fullerene-like molecular structures but lacking carbon include MoS2, WS2, TiS2 and NbS2. Under isostatic pressure, these new materials were found to be stable up to at least 350 tons/cm2 (34.3 GPa).[40]

Properties

In the early 2000s, the chemical and physical properties of fullerenes were a hot topic in the field of research and development. Popular Science discussed possible uses of fullerenes (graphene) in armor.[41] In April 2003, fullerenes were under study for potential medicinal use: binding specific antibiotics to the structure to target resistant bacteria and even target certain cancer cells such as melanoma. The October 2005 issue of Chemistry & Biology contained an article describing the use of fullerenes as light-activated antimicrobial agents.[42]

In the field of nanotechnology, heat resistance and superconductivity are some of the more heavily studied properties.

A common method used to produce fullerenes is to send a large current between two nearby graphite electrodes in an inert atmosphere. The resulting carbon plasma arc between the electrodes cools into sooty residue from which many fullerenes can be isolated.

There are many calculations that have been done using ab-initio quantum methods applied to fullerenes. By DFT and TD-DFT methods one can obtain IR, Raman and UV spectra. Results of such calculations can be compared with experimental results.

Aromaticity

Researchers have been able to increase the reactivity of fullerenes by attaching active groups to their surfaces. Buckminsterfullerene does not exhibit "superaromaticity": that is, the electrons in the hexagonal rings do not delocalize over the whole molecule.

A spherical fullerene of n carbon atoms has n pi-bonding electrons, free to delocalize. These should try to delocalize over the whole molecule. The quantum mechanics of such an arrangement should be like one shell only of the well-known quantum mechanical structure of a single atom, with a stable filled shell for n = 2, 8, 18, 32, 50, 72, 98, 128, etc.; i.e. twice a perfect square number; but this series does not include 60. This 2(N + 1)2 rule (with N integer) for spherical aromaticity is the three-dimensional analogue of Hückel's rule. The 10+ cation would satisfy this rule, and should be aromatic. This has been shown to be the case using quantum chemical modelling, which showed the existence of strong diamagnetic sphere currents in the cation.[43]

As a result, C60 in water tends to pick up two more electrons and become an anion. The nC60 described below may be the result of C60 trying to form a loose metallic bond.

Chemistry

Fullerenes are stable, but not totally unreactive. The sp2-hybridized carbon atoms, which are at their energy minimum in planar graphite, must be bent to form the closed sphere or tube, which produces angle strain. The characteristic reaction of fullerenes is electrophilic addition at 6,6-double bonds, which reduces angle strain by changing sp2-hybridized carbons into sp3-hybridized ones. The change in hybridized orbitals causes the bond angles to decrease from about 120° in the sp2 orbitals to about 109.5° in the sp3 orbitals. This decrease in bond angles allows for the bonds to bend less when closing the sphere or tube, and thus, the molecule becomes more stable.

Other atoms can be trapped inside fullerenes to form inclusion compounds known as endohedral fullerenes. An unusual example is the egg-shaped fullerene Tb3N@C84, which violates the isolated pentagon rule.[44] Recent evidence for a meteor impact at the end of the Permian period was found by analyzing noble gases so preserved.[45] Metallofullerene-based inoculates using the rhonditic steel process are beginning production as one of the first commercially viable uses of buckyballs.

Solubility

Fullerenes are sparingly soluble in many solvents. Common solvents for the fullerenes include aromatics, such as toluene, and others like carbon disulfide. Solutions of pure buckminsterfullerene have a deep purple color. Solutions of C70 are a reddish brown. The higher fullerenes C76 to C84 have a variety of colors. C76 has two optical forms, while other higher fullerenes have several structural isomers. Fullerenes are the only known allotrope of carbon that can be dissolved in common solvents at room temperature.

| Solvent | C60 mg/mL |

C70 mg/mL |

|---|---|---|

| 1-chloronaphthalene | 51 | ND |

| 1-methylnaphthalene | 33 | ND |

| 1,2-dichlorobenzene | 24 | 36.2 |

| 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene | 18 | ND |

| tetrahydronaphthalene | 16 | ND |

| carbon disulfide | 8 | 9.875 |

| 1,2,3-tribromopropane | 8 | ND |

| chlorobenzene | 7 | ND |

| p-xylene | 5 | 3.985 |

| bromoform | 5 | ND |

| cumene | 4 | ND |

| toluene | 3 | 1.406 |

| benzene | 1.5 | 1.3 |

| carbon tetrachloride | 0.447 | 0.121 |

| chloroform | 0.25 | ND |

| n-hexane | 0.046 | 0.013 |

| cyclohexane | 0.035 | 0.08 |

| tetrahydrofuran | 0.006 | ND |

| acetonitrile | 0.004 | ND |

| methanol | 4.0×10−5 | ND |

| water | 1.3×10−11 | ND |

| pentane | 0.004 | 0.002 |

| heptane | ND | 0.047 |

| octane | 0.025 | 0.042 |

| isooctane | 0.026 | ND |

| decane | 0.070 | 0.053 |

| dodecane | 0.091 | 0.098 |

| tetradecane | 0.126 | ND |

| acetone | ND | 0.0019 |

| isopropanol | ND | 0.0021 |

| dioxane | 0.0041 | ND |

| mesitylene | 0.997 | 1.472 |

| dichloromethane | 0.254 | 0.080 |

| ND, not determined | ||

Some fullerene structures are not soluble because they have a small band gap between the ground and excited states. These include the small fullerenes C28,[46] C36 and C50. The C72 structure is also in this class, but the endohedral version with a trapped lanthanide-group atom is soluble due to the interaction of the metal atom and the electronic states of the fullerene. Researchers had originally been puzzled by C72 being absent in fullerene plasma-generated soot extract, but found in endohedral samples. Small band gap fullerenes are highly reactive and bind to other fullerenes or to soot particles.

Solvents that are able to dissolve buckminsterfullerene (C60 and C70) are listed at left in order from highest solubility. The solubility value given is the approximate saturated concentration.[47][48][49][50][51]

Solubility of C60 in some solvents shows unusual behaviour due to existence of solvate phases (analogues of crystallohydrates). For example, solubility of C60 in benzene solution shows maximum at about 313 K. Crystallization from benzene solution at temperatures below maximum results in formation of triclinic solid solvate with four benzene molecules C60·4C6H6 which is rather unstable in air. Out of solution, this structure decomposes into usual face-centered cubic (fcc) C60 in few minutes' time. At temperatures above solubility maximum the solvate is not stable even when immersed in saturated solution and melts with formation of fcc C60. Crystallization at temperatures above the solubility maximum results in formation of pure fcc C60. Millimeter-sized crystals of C60 and C70 can be grown from solution both for solvates and for pure fullerenes.[52][53]

Quantum mechanics

In 1999, researchers from the University of Vienna demonstrated that wave-particle duality applied to molecules such as fullerene.[54]

Superconductivity

Chirality

Some fullerenes (e.g. C76, C78, C80, and C84) are inherently chiral because they are D2-symmetric, and have been successfully resolved. Research efforts are ongoing to develop specific sensors for their enantiomers.

Construction

Two theories have been proposed to describe the molecular mechanisms that make fullerenes. The older, “bottom-up” theory proposes that they are built atom-by-atom. The alternative “top-down” approach claims that fullerenes form when much larger structures break into constituent parts.[55]

In 2013 researchers discovered that asymmetrical fullerenes formed from larger structures settle into stable fullerenes. The synthesized substance was a particular metallofullerene consisting of 84 carbon atoms with two additional carbon atoms and two yttrium atoms inside the cage. The process produced approximately 100 micrograms.[55]

However, they found that the asymmetrical molecule could theoretically collapse to form nearly every known fullerene and metallofullerene. Minor perturbations involving the breaking of a few molecular bonds cause the cage to become highly symmetrical and stable. This insight supports the theory that fullerenes can be formed from graphene when the appropriate molecular bonds are severed.[55][56]

Production technology

Fullerene production processes comprise the following five subprocesses: (i) synthesis of fullerenes or fullerene-containing soot; (ii) extraction; (iii) separation (purification) for each fullerene molecule, yielding pure fullerenes such as C60; (iv) synthesis of derivatives (mostly using the techniques of organic synthesis); (v) other post-processing such as dispersion into a matrix. The two synthesis methods used in practice are the arc method, and the combustion method. The latter, discovered at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is preferred for large scale industrial production.[57][58]

Applications

Fullerenes have been extensively used for several biomedical applications including the design of high-performance MRI contrast agents, X-ray imaging contrast agents, photodynamic therapy and drug and gene delivery, summarized in several comprehensive reviews.[59]

Tumor research

While past cancer research has involved radiation therapy, photodynamic therapy is important to study because breakthroughs in treatments for tumor cells will give more options to patients with different conditions. Recent experiments using HeLa cells in cancer research involves the development of new photosensitizers with increased ability to be absorbed by cancer cells and still trigger cell death. It is also important that a new photosensitizer does not stay in the body for a long time to prevent unwanted cell damage.[60]

Fullerenes can be made to be absorbed by HeLa cells. The C60 derivatives can be delivered to the cells by using the functional groups L-phenylalanine, folic acid, and L-arginine among others.[61] Functionalizing the fullerenes aims to increase the solubility of the molecule by the cancer cells. Cancer cells take up these molecules at an increased rate because of an upregulation of transporters in the cancer cell, in this case amino acid transporters will bring in the L-arginine and L-phenylalanine functional groups of the fullerenes.[62]

Once absorbed by the cells, the C60 derivatives would react to light radiation by turning molecular oxygen into reactive oxygen which triggers apoptosis in the HeLa cells and other cancer cells that can absorb the fullerene molecule. This research shows that a reactive substance can target cancer cells and then be triggered by light radiation, minimizing damage to surrounding tissues while undergoing treatment.[63]

When absorbed by cancer cells and exposed to light radiation, the reaction that creates reactive oxygen damages the DNA, proteins, and lipids that make up the cancer cell. This cellular damage forces the cancerous cell to go through apoptosis, which can lead to the reduction in size of a tumor. Once the light radiation treatment is finished the fullerene will reabsorb the free radicals to prevent damage of other tissues.[64] Since this treatment focuses on cancer cells, it is a good option for patients whose cancer cells are within reach of light radiation. As this research continues, the treatment may penetrate deeper into the body and be absorbed by cancer cells more effectively.[60]

Safety and toxicity

A comprehensive and recent review on fullerene toxicity is given by Lalwani et al.[59] These authors review the works on fullerene toxicity beginning in the early 1990s to present, and conclude that very little evidence gathered since the discovery of fullerenes indicate that C60 is toxic. The toxicity of these carbon nanoparticles is not only dose and time-dependent, but also depends on a number of other factors such as: type (e.g., C60, C70, M@C60, M@C82, functional groups used to water solubilize these nanoparticles (e.g., OH, COOH), and method of administration (e.g., intravenous, intraperitoneal). The authors therefore recommend that pharmacology of every new fullerene- or metallofullerene-based complex must be assessed individually as a different compound.

Popular culture

Examples of fullerenes in popular culture are numerous. Fullerenes appeared in fiction well before scientists took serious interest in them. In a humorously speculative 1966 column for New Scientist, David Jones suggested that it may be possible to create giant hollow carbon molecules by distorting a plane hexagonal net by the addition of impurity atoms.[65]

On 4 September 2010, Google used an interactively rotatable fullerene[66] C60 as the second 'o' in their logo to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the discovery of the fullerenes.[67][68]

See also

References

- ↑ "Fullerene", Encyclopædia Britannica on-line

- ↑ Iijima, S (1980). "Direct observation of the tetrahedral bonding in graphitized carbon black by high resolution electron microscopy". Journal of Crystal Growth. 50 (3): 675–683. Bibcode:1980JCrGr..50..675I. doi:10.1016/0022-0248(80)90013-5.

- 1 2 Buseck, P.R.; Tsipursky, S.J.; Hettich, R. (1992). "Fullerenes from the Geological Environment". Science. 257 (5067): 215–7. Bibcode:1992Sci...257..215B. doi:10.1126/science.257.5067.215. PMID 17794751.

- ↑ Cami, J; Bernard-Salas, J.; Peeters, E.; Malek, S. E. (2 September 2010). "Detection of C60 and C70 in a Young Planetary Nebula". Science. 329 (5996): 1180–2. Bibcode:2010Sci...329.1180C. doi:10.1126/science.1192035. PMID 20651118.

- ↑ Atkinson, Nancy (27 October 2010). "Buckyballs Could Be Plentiful in the Universe". Universe Today. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ↑ Belkin, A.; et., al. (2015). "Self-Assembled Wiggling Nano-Structures and the Principle of Maximum Entropy Production". Sci. Rep. 5. Bibcode:2015NatSR...5E8323B. doi:10.1038/srep08323.

- ↑ Schultz, H.P. (1965). "Topological Organic Chemistry. Polyhedranes and Prismanes". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 30 (5): 1361–1364. doi:10.1021/jo01016a005.

- ↑ Osawa, E. (1970). "Superaromaticity". Kagaku. 25: 854–863.

- ↑ Halford, B. (9 October 2006). "The World According to Rick". Chemical & Engineering News. 84 (41): 13–19. doi:10.1021/cen-v084n041.p013.

- ↑ Thrower, P.A. (1999). "Editorial". Carbon. 37 (11): 1677–1678. doi:10.1016/S0008-6223(99)00191-8.

- ↑ Henson, R.W. "The History of Carbon 60 or Buckminsterfullerene". Archived from the original on 15 June 2013.

- ↑ Bochvar, D.A.; Galpern, E.G. (1973). "О гипотетических системах: карбододекаэдре, s-икосаэдре и карбо-s-икосаэдре" [On hypothetical systems: carbon dodecahedron, S-icosahedron and carbon-S-icosahedron]. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR. 209: 610.

- ↑ Kroto, H.W.; Heath, J. R.; Obrien, S. C.; Curl, R. F.; Smalley, R. E. (1985). "C60: Buckminsterfullerene". Nature. 318 (6042): 162–163. Bibcode:1985Natur.318..162K. doi:10.1038/318162a0.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1996". Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ↑ Mraz, S.J. (14 April 2005). "A new buckyball bounces into town". Machine Design. Archived from the original on 13 October 2008.

- ↑ Iijima, Sumio (1991), "Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon", Nature, 354: 56–58, Bibcode:1991Natur.354...56I, doi:10.1038/354056a0

- ↑ "The allotropes of carbon". Interactive Nano-Visualization in Science & Engineering Education. Archived from the original on 18 June 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ↑ Stars reveal carbon 'spaceballs', BBC, 22 July 2010.

- ↑ Buckminsterfullerene, C60. Sussex Fullerene Group. chm.bris.ac.uk

- ↑ Miessler, G.L.; Tarr, D.A. (2004). Inorganic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Pearson Education. ISBN 0-13-120198-0.

- ↑ Mitchel, D.R.; Brown, R. Malcolm Jr. (2001). "The Synthesis of Megatubes: New Dimensions in Carbon Materials". Inorganic Chemistry. 40 (12): 2751–5. doi:10.1021/ic000551q. PMID 11375691.

- ↑ Hiorns, R.C.; Cloutet, Eric; Ibarboure, Emmanuel; Khoukh, Abdel; Bejbouji, Habiba; Vignau, Laurence; Cramail, Henri (2010). "Synthesis of Donor-Acceptor Multiblock Copolymers Incorporating Fullerene Backbone Repeat Units". Macromolecules. 14. 43 (14): 6033–6044. Bibcode:2010MaMol..43.6033H. doi:10.1021/ma100694y.

- ↑ Ugarte, D. (1992). "Curling and closure of graphitic networks under electron-beam irradiation". Nature. 359 (6397): 707–709. Bibcode:1992Natur.359..707U. doi:10.1038/359707a0. PMID 11536508.

- ↑ Sano, N.; Wang, H.; Chhowalla, M.; Alexandrou, I.; Amaratunga, G. A. J. (2001). "Synthesis of carbon 'onions' in water". Nature. 414 (6863): 506–7. Bibcode:2001Natur.414..506S. doi:10.1038/35107141. PMID 11734841.

- ↑ Shvartsburg, A.A.; Hudgins, R. R.; Gutierrez, Rafael; Jungnickel, Gerd; Frauenheim, Thomas; Jackson, Koblar A.; Jarrold, Martin F. (1999). "Ball-and-Chain Dimers from a Hot Fullerene Plasma" (PDF). Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 103 (27): 5275–5284. Bibcode:1999JPCA..103.5275S. doi:10.1021/jp9906379.

- ↑ Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Du, Shixuan; Liu, Ruozhuang (2001). "Structures and stabilities of C60-rings". Chemical Physics Letters. 335 (5–6): 524–532. Bibcode:2001CPL...335..524L. doi:10.1016/S0009-2614(01)00064-1.

- ↑ Qiao, Rui; Roberts, Aaron P.; Mount, Andrew S.; Klaine, Stephen J.; Ke, Pu Chun (2007). "Translocation of C60 and Its Derivatives Across a Lipid Bilayer". Nano Letters. 7 (3): 614–9. Bibcode:2007NanoL...7..614Q. doi:10.1021/nl062515f. PMID 17316055.

- ↑ Gonzalez Szwacki, N.; Sadrzadeh, A.; Yakobson, B. (2007). "B80 Fullerene: An Ab Initio Prediction of Geometry, Stability, and Electronic Structure". Physical Review Letters. 98 (16): 166804. Bibcode:2007PhRvL..98p6804G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.166804. PMID 17501448.

- 1 2 Gopakumar, G.; Nguyen, M.T.; Ceulemans, A. (2008). "The boron buckyball has an unexpected Th symmetry". Chemical Physics Letters. 450 (4–6): 175–177. arXiv:0708.2331. Bibcode:2008CPL...450..175G. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2007.11.030.

- ↑ Prasad, D.; Jemmis, E. (2008). "Stuffing Improves the Stability of Fullerenelike Boron Clusters". Physical Review Letters. 100 (16): 165504. Bibcode:2008PhRvL.100p5504P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.165504. PMID 18518216.

- ↑ De, S.; Willand, A.; Amsler, M.; Pochet, P.; Genovese, L.; Goedecker, S. (2011). "Energy Landscape of Fullerene Materials: A Comparison of Boron to Boron Nitride and Carbon". Physical Review Letters. 106 (22): 225502. arXiv:1012.3076. Bibcode:2011PhRvL.106v5502D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.225502. PMID 21702613.

- ↑ Locke, W. (13 October 1996). "Buckminsterfullerene: Molecule of the Month". Imperial College. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ↑ Meija, J. (2006). "Goldberg Variations Challenge" (PDF). Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 385: 6–7. doi:10.1007/s00216-006-0358-9.

- ↑ Fowler, P. W. and Manolopoulos, D. E. Cn Fullerenes. nanotube.msu.edu

- ↑ Harris, D.J. "Discovery of Nitroballs: Research in Fullerene Chemistry" http://www.usc.edu/CSSF/History/1993/CatWin_S05.html

- ↑ Charles Gause. "Fullerene Nanomedicines for Medical and Healthcare Applications".

- ↑ "Luna Inc. Organic Photovoltaic Technology". 2014. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014.

- ↑ Pushparaj, V.L.; Shaijumon, Manikoth M.; Kumar, A.; Murugesan, S.; Ci, L.; Vajtai, R.; Linhardt, R. J.; Nalamasu, O.; Ajayan, P. M. (2007). "Flexible energy storage devices based on nanocomposite paper". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (34): 13574–7. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10413574P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0706508104. PMC 1959422. PMID 17699622.

- ↑ Blank, V.; Popov, M.; Pivovarov, G.; Lvova, N.; Gogolinsky, K.; Reshetov, V. (1998). "Ultrahard and superhard phases of fullerite C60: Comparison with diamond on hardness and wear". Diamond and Related Materials. 7 (2–5): 427–431. Bibcode:1998DRM.....7..427B. doi:10.1016/S0925-9635(97)00232-X.

- ↑ Genuth, Iddo; Yaffe, Tomer (February 15, 2006). "Protecting the soldiers of tomorrow". IsraCast.

- ↑ Erik Sofge (12 February 2014). "How Real Is 'RoboCop'?". Popular Science.

- ↑ Tegos, G. P.; Demidova, T. N.; Arcila-Lopez, D.; Lee, H.; Wharton, T.; Gali, H.; Hamblin, M. R. (2005). "Cationic Fullerenes Are Effective and Selective Antimicrobial Photosensitizers". Chemistry & Biology. 12 (10): 1127–1135. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.08.014. PMC 3071678. PMID 16242655.

- ↑ Johansson, M.P.; Jusélius, J.; Sundholm, D. (2005). "Sphere Currents of Buckminsterfullerene". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 44 (12): 1843–6. doi:10.1002/anie.200462348. PMID 15706578.

- ↑ Beavers, C.M.; Zuo, T. (2006). "Tb3N@C84: An improbable, egg-shaped endohedral fullerene that violates the isolated pentagon rule". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 128 (35): 11352–3. doi:10.1021/ja063636k. PMID 16939248.

- ↑ Luann, B.; Poreda, Robert J.; Hunt, Andrew G.; Bunch, Theodore E.; Rampino, Michael (2007). "Impact Event at the Permian-Triassic Boundary: Evidence from Extraterrestrial Noble Gases in Fullerenes". Science. 291 (5508): 1530–3. Bibcode:2001Sci...291.1530B. doi:10.1126/science.1057243. PMID 11222855.

- ↑ Guo, T.; Smalley, R.E.; Scuseria, G.E. (1993). "Ab initio theoretical predictions of C28, C28H4, C28F4, (Ti@C28)H4, and M@C28 (M = Mg, Al, Si, S, Ca, Sc, Ti, Ge, Zr, and Sn)". Journal of Chemical Physics. 99 (1): 352. Bibcode:1993JChPh..99..352G. doi:10.1063/1.465758.

- ↑ Beck, Mihály T.; Mándi, Géza (1997). "Solubility of C60". Fullerenes, Nanotubes and Carbon Nanostructures. 5 (2): 291–310. doi:10.1080/15363839708011993.

- ↑ Bezmel'nitsyn, V.N.; Eletskii, A.V.; Okun', M.V. (1998). "Fullerenes in solutions". Physics-Uspekhi. 41 (11): 1091–1114. Bibcode:1998PhyU...41.1091B. doi:10.1070/PU1998v041n11ABEH000502.

- ↑ Ruoff, R.S.; Tse, Doris S.; Malhotra, Ripudaman; Lorents, Donald C. (1993). "Solubility of fullerene (C60) in a variety of solvents" (PDF). Journal of Physical Chemistry. 97 (13): 3379–3383. doi:10.1021/j100115a049.

- ↑ Sivaraman, N.; Dhamodaran, R.; Kaliappan, I.; Srinivasan, T. G.; Vasudeva Rao, P. R. P.; Mathews, C. K. C. (1994). "Solubility of C70 in Organic Solvents". Fullerene Science and Technology. 2 (3): 233–246. doi:10.1080/15363839408009549.

- ↑ Semenov, K. N.; Charykov, N. A.; Keskinov, V. A.; Piartman, A. K.; Blokhin, A. A.; Kopyrin, A. A. (2010). "Solubility of Light Fullerenes in Organic Solvents". Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data. 55: 13–36. doi:10.1021/je900296s.

- ↑ Talyzin, A.V. (1997). "Phase Transition C60−C60*4C6H6 in Liquid Benzene". Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 101 (47): 9679–9681. doi:10.1021/jp9720303.

- ↑ Talyzin, A.V.; Engström, I. (1998). "C70 in Benzene, Hexane, and Toluene Solutions". Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 102 (34): 6477–6481. doi:10.1021/jp9815255.

- ↑ Arndt, M.; Nairz, Olaf; Vos-Andreae, Julian; Keller, Claudia; Van Der Zouw, Gerbrand; Zeilinger, Anton (1999). "Wave-particle duality of C60" (PDF). Nature. 401 (6754): 680–2. Bibcode:1999Natur.401..680A. doi:10.1038/44348. PMID 18494170.

- 1 2 3 Support for top-down theory of how 'buckyballs’ form. kurzweilai.net. 24 September 2013

- ↑ Zhang, J.; Bowles, F. L.; Bearden, D. W.; Ray, W. K.; Fuhrer, T.; Ye, Y.; Dixon, C.; Harich, K.; Helm, R. F.; Olmstead, M. M.; Balch, A. L.; Dorn, H. C. (2013). "A missing link in the transformation from asymmetric to symmetric metallofullerene cages implies a top-down fullerene formation mechanism". Nature Chemistry. 5 (10): 880–885. Bibcode:2013NatCh...5..880Z. doi:10.1038/nchem.1748. PMID 24056346.

- ↑ Osawa, Eiji (2002). Perspectives of Fullerene Nanotechnology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 29–. ISBN 978-0-7923-7174-8.

- ↑ Arikawa, Mineyuki (2006). "Fullerenes—an attractive nano carbon material and its production technology". Nanotechnology Perceptions. 2 (3): 121–128. ISSN 1660-6795.

- 1 2 G. Lalwani and B. Sitharaman, Multifunctional fullerene and metallofullerene based nanobiomaterials, NanoLIFE 08/2013; 3:1342003. DOI: 10.1142/S1793984413420038 Full Text PDF

- 1 2 Brown, S.B.; Brown, E.A.; Walker, I. (2004). "The present and future role of photodynamic therapy in cancer treatment". Lancet Oncology. 5 (8): 497–508. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01529-3. PMID 15288239.

- ↑ Mroz, Pawel; Pawlak, Anna; Satti, Minahil; Lee, Haeryeon; Wharton, Tim; Gali, Hariprasad; Sarna, Tadeusz; Hamblin, Michael R. (2007). "Functionalized fullerenes mediate photodynamic killing of cancer cells: type I versus typee II photochemical mechanism". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 43 (5): 711–719. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.05.005. PMC 1995806. PMID 17664135.

- ↑ Ganapathy, Vadivel; Thanaraju, Muthusamy; Prasad, Puttur D. (2009). "Nutrient transporters in cancer: Relevance to Warburg hypothesis and beyond". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 121 (1): 29–40. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.09.005. PMID 18992769.

- ↑ Hu, Zhen; Zhang, Chunhua; Huang, Yudong; Sun, Shaofan; Guan, Wenchao; Yao, Yuhuan (2012). "Photodynamic anticancer activities of water-soluble C60 derivatives and their biolgoical consequences in a HeLa cell line". Chemico-biological interactions. 195 (1): 86–94. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2011.11.003. PMID 22108244.

- ↑ Markovic, Zoran; Trajkovic, Vladimir (2008). "Biomedical potential of the reactive oxygen species generation and quenching by fullerenes". Biomaterials. 29 (26): 3561–3573. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.05.005. PMID 18534675.

- ↑ Jones, D. (1966). "Note in Ariadne column". New Scientist. 32: 245.

- ↑ Google archive of the Sep. 4 2010 logo

- ↑ 25th anniversary of the Buckyball celebrated by interactive Google Doodle, The Daily Telegraph. 4 September 2010

- ↑ Google doodle marks buckyball anniversary. The Guardian. 4 September 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fullerene. |

- Properties of C60 fullerene

- Richard Smalley's autobiography at Nobel.se

- Sir Harry Kroto's webpage

- Simple model of Fullerene

- Rhonditic Steel

- Introduction to fullerites

- Bucky Balls, a short video explaining the structure of C60 by the Vega Science Trust

- Giant Fullerenes, a short video looking at Giant Fullerenes

- Graphene, 15 September 2010, BBC Radio program Discovery