Friedrich Martens

Friedrich Fromhold Martens, or Friedrich Fromhold von Martens,[1] also known as Fyodor Fyodorovich Martens (Фёдор Фёдорович Мартенс) in Russian and Frédéric Frommhold (de) Martens in French (27 August [O.S. 15 August] 1845 – 19 June [O.S. 6 June] 1909) was a diplomat and jurist in service of the Russian Empire who made important contributions to the science of international law. He represented Russia at the Hague Peace Conferences (during which he drafted the Martens Clause) and helped to settle the first cases of international arbitration, notably the dispute between France and the United Kingdom over Newfoundland. As a scholar, he is probably best remembered today for having edited 15 volumes of Russian international treaties (1874–1909).

Biography

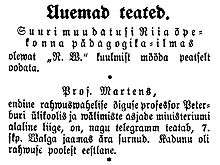

"Professor Martens, Professor of International Law at the Saint Petersburg University, a member of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has died according to the telegram at the Valga, Estonia train station on June 7. The deceased was an ethnic Estonian."

Born to ethnic Estonians[2][3][4][5][6] parents at Pärnu in the Governorate of Livonia of Russian Empire, Martens was later raised and educated as a German-speaker. He lost both parents at the age of nine and was sent to a Lutheran orphanage in St. Petersburg, where he successfully completed the full course of studies at a German high school and in 1863 entered the law faculty of St. Petersburg University. In 1868, he started his service at the Russian ministry of foreign affairs. In 1871, he became a lecturer in international law in the university of St. Petersburg, and in 1872 professor of public law in the Imperial School of Law and the Imperial Alexander Lyceum. In 1874, he was selected special legal assistant to Prince Gorchakov, then imperial chancellor.

His book on The Right of Private Property in War had appeared in 1869, and had been followed in 1873 by that upon The Office of Consul and Consular Jurisdiction in the East, which had been translated into German and republished at Berlin. These were the first of a long series of studies which won for their author a worldwide reputation, and raised the character of the Russian school of international jurisprudence in all civilised countries.

First amongst them must be placed the great Recueil des traités et conventions conclus par la Russie avec les puissances etrangeres (13 volumes, 1874–1902). This collection, published in Russian and French in parallel columns, contains not only the texts of the treaties but valuable introductions dealing with the diplomatic conditions of which the treaties were the outcome. These introductions are based largely on unpublished documents from the Russian archives.

Of Martens' original works his International Law of Civilised Nations is perhaps the best known.[7] It was written in Russian, a German edition appearing in 1884–1885, and a French edition in 1883-1887.[8] It displays much judgment and acumen, though some of the doctrines which it defends by no means command universal assent. More openly biased in character are such treatises as:

- Russia and England in Central Asia (1879)

- Russia's Conflict with China (1881)

- The Egyptian Question (1882)

- The African Conference of Berlin and the Colonial Policy of Modern States (1887)

In the delicate questions raised in some of these works Martens stated his case with learning and ability, even when it was obvious that he was arguing as a special pleader. Martens was repeatedly chosen to act in international arbitrations. Among the controversies which he sat as judge or arbitrator were: the Pious Fund Affair, between Mexico and the United States – the first case determined by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague – and the dispute between Great Britain and France over Newfoundland in 1891. He was the presiding arbitrator in the arbitration of the boundary dispute between Venezuela and British Guiana which followed the Venezuela Crisis of 1895.

He played an important part in the negotiations between his own country and Japan, which led to the peace of Portsmouth (August 1905) and prepared the way for the Russo-Japanese convention. He was employed in laying the foundations for the Hague Peace Conferences. He was one of the Russian plenipotentiaries at the first conference and president of the fourth committee – that on maritime law – at the second conference. His visits to the chief capitals of Europe in the early part of 1907 were an important preliminary in the preparation of the programme. He was judge of the Russian supreme prize court established to determine cases arising during the war with Japan.

He received honorary degrees from the universities of Oxford (D.C.L. October 1902 in connection with the tercentenary of the Bodleian Library[9]), Cambridge, Edinburgh and Yale (LL.D. October 1901[10]); he was also one of the runner-up nominees for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1902. In April 1907, he addressed a remarkable letter to The Times on the position of the second Duma, in which he argued that the best remedy for the ills of Russia would be the dissolution of that assembly and the election of another on a narrower franchise. He died suddenly in June 1909.

Ennoblement

The date and circumstances of his ennoblement are not clear. While it is undisputed that he called himself and was referred to as von or de Martens in publications since the early 1870s, this title might have been bestowed upon him either with one of the more distinguished Russian Orders, or with the title of a Privy Councillor (according to the Table of Ranks), or simply with his appointment as a full professor. He was never registered in the matricles of the knightage of Livonia (Livländische Ritterschaft) or one of the other three Baltic knightages (that is of Estonia, Courland and Ösel/Saaremaa). His surname, Martens, is included in the Russian Heraldic Book No. 14, though it is uncertain if this entry relates to him or to another noble of the same name. His social advancement was the more remarkable, as it was exclusively based on his professional merits.

Popular culture

- Friedrich Martens is featured as the main character in the novel Professor Martens' Departure (Professor Martensi ärasõit, 1984) by Estonian author Jaan Kross.

Criticism

In 1952, the German émigré scholar in the US, Arthur Nussbaum, himself the author of a well-received history of the law of nations, published an article on Martens, which still makes waves.[11]

Nussbaum set himself the task of analysing the 'writings and actions' of Martens. First, he turned his attention to Martens' celebrated two-volume textbook and pointed out several pro-Russian gaps and biases in its historical part:

"Flagrant lack of objectivity and conscientiousness. The Tsars and Tsarinas invariably appear as pure representatives of peace, conciliation, moderation and justice, whereas the moral qualities of their non-Russian opponents leave much to be desired."

Nussbaum pointed out that Martens gave an extensive meaning to the notion of "international administrative law," even including war in the field of international administration, and emphasized that the supreme principle of international administrative law was expediency. Nussbaum was very critical of the application of that concept:

"Expanding the range of international administrative law meant, therefore, expanding the dominance of expediency – which is the very opposite of law."

Further, Nussbaum turned his attention to the other (publicist) writings of Martens, mostly the ones published in Revue de droit international et de législation comparée. Nussbaum noted that they were invariably signed by de Martens as professor of international law at the University of St. Petersburg and as member of the Institut de Droit International. Martens did not mention his high position in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The articles were thus only unrestrained briefs for various actions of the Russian government.

For example, Nussbaum concluded that the 1874 article by Martens on the Brussels conference, "It is purely apologetic and has nothing to do with law."

Then, Nussbaum turned to Martens's activities as arbitrator and found them "most conspicuous." In particular, Nussbaum referred to a memorandum of Venezuelan lawyer Severo Mellet Provost that had been made public posthumously. The memorandum made the claim that Martens had approached his fellow US arbitrators-judges with an ultimatum: either they agreed with a generally pro-British solution or Martens, as umpire, would join the British arbitrators in a solution that would be even more against Venezuela. Nussbaum held that Mr Provost's account seemed "entirely credible in all essential parts" and concluded:

"The spirit of arbitration will be perverted more seriously if the neutral arbitrator does not possess the external and internal independence from his government, which, according to the conception of most countries of Western civilization, is an essential attrribute of judicial office. That independence de Martens certainly did not have, and it is difficult to see how he could have acquired it within the framework of the Tsarist regime and tradition."

Finally, Nussbaum concluded:

"It appears that de Martens did not think of international law as something different from, and in a sense above, diplomacy.… de Martens considered in his professional duty as a scholar and writer on international law to defend and back up the policies of his government at any price.… Obviously his motivation was overwhelmingly, if not exclusively, political and patriotic. Legal argument served him as a refined art to tender his pleas for Russian claims more impressive or more palatable. He was not really a man of law...."

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Friedrich Martens should not be confused with Georg Friedrich von Martens (1756–1821) who was incidentally also an international lawyer, born in Hamburg. He was professor of international law at the University of Göttingen (1783–89), a state councilor of Westphalia (1808–13), and the representative of the King of Hanover in the German Confederal diet of Frankfurt upon Main (1816–21).

- ↑ "Martens was of Estonian ethnic origin, an issue thoroughly researched recently in Estonia on the basis of complicated church and orphanage records." Richard B. Bilder & W. E. Butler, "Professor Martens' Departure by Jaan Kross", book review, American Journal of International Law (1994), No. 4, page 864.

- ↑ Death notice in Postimees daily, page 3 of June 8, 1909 (OS) issue, image available in an online .

- ↑ Suur rahuehitaja

- ↑ Vladimir Vasilʹevich Pustogarov, William Elliott Butler (2000). Our Martens. Kluwer Law International. ISBN 90-411-9602-1.

- ↑ Estonian Soviet Encyclopedia, 1973, (volume 5)

- ↑ Мартенс, Федер Федерович (1882). Современное международное право цивилизованных народов. СПб.: Тип. Министерства путей сообщения (А. Бенке). Retrieved 25 October 2017 – via ЕНИП - ЭЛЕКТРОННАЯ БИБЛИОТЕКА "НАУЧНОЕ НАСЛЕДИЕ РОССИИ".

- ↑ Martens, F. De (1883). Traité de droit international traduit du russe par Alfred Lèo. Paris: Librairie A. Marescq. Aine. Retrieved 25 October 2017 – via Internet Archive. ; Martens, F. De (1886). Traité de droit international traduit du russe par Alfred Lèo. II. Paris: Librairie A. Marescq. Aine. Retrieved 25 October 2017 – via Gallica. ; Martens, F. De (1887). Traité de droit international traduit du russe par Alfred Lèo. III. Paris: Librairie A. Marescq. Aine. Retrieved 25 October 2017 – via Gallica.

- ↑ "University intelligence". The Times (36893). London. 8 October 1902. p. 4.

- ↑ "United States". The Times (36594). London. October 24, 1901. p. 3.

- ↑ Nussbaum, Arthur (1952), "Frederic de Martens - Representative Tsarist Writer on International Law", Nordisk Tidsskrift International Ret, 22, pp. 51–66 – via HeinOnline

Biographies

- Vladimir Pustogarov. (English version 2000) "Our Martens: F.F. Martens, International Lawyer and Architect of Peace". The original,"С пальмовой ветвью мира" was published in 1993.

Articles

- Fleck, Dieter. "Friedrich von Martens: A Great International Lawyer from Pärnu", 2 Baltic Defense Review (2003), pp. 19–26

- Pustogarov, Vladimir V (June 30, 1996). "Fyodor Fyodorovich Martens (1845–1909) – A Humanist of Modern Times". International Review of the Red Cross (132): 300–314. Retrieved June 1, 2012.

- "Frederic de Martens". American Journal of International Law. American Society of International Law. 3 (4): 983–85. October 1909. doi:10.2307/2186432. JSTOR 2186432.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Friedrich Fromhold Martens. |

- The Martens Society

- DE MARTENS HAS HOPE FOR RUSSIA The New York Times, June 10, 1907 Special Cablegram