Freedom of religion by country

The status of religious freedom around the world varies from country to country. States can differ based on whether or not they guarantee equal treatment under law for followers of different religions, whether they establish a state religion (and the legal implications that this has for both practitioners and non-practitioners), the extent to which religious organizations operating within the country are policed, and the extent to which religious law is used as a basis for the country's legal code.

There are further discrepancies between some countries' self-proclaimed stances of religious freedom in law and the actual practice of authority bodies within those countries: a country's establishment of religious equality in their constitution or laws does not necessarily translate into freedom of practice for residents of the country. Additionally, similar practices (such as having citizens identify their religious preference to the government or on identification cards) can have different consequences depending on other sociopolitical circumstances specific to the countries in question.

Over 120 national constitutions mention equality regardless of religion.[1]

Africa

Algeria

Freedom of religion in Algeria is regulated by the Algerian Constitution, which declares Islam to be the state religion (Article 2) but also declares that "freedom of creed and opinion is inviolable" (Article 36); it prohibits discrimination, Article 29 states "All citizens are equal before the law. No discrimination shall prevail because of birth, race, sex, opinion or any other personal or social condition or circumstance". In practice, the government generally respects this, with some limited exceptions. The government follows a de facto policy of tolerance by allowing, in limited instances, the conduct of religious services by non-Muslim faiths in the capital which are open to the public. The small Christian and tiny Jewish populations generally practice their faiths without government interference. The law does not recognize marriages between Muslim women and non-Muslim men; it does however recognise marriages between Muslim men and non-Muslim women. By law, children follow the religion of their fathers, even if they are born abroad and are citizens of their (non-Muslim) country of birth.

Angola

The Constitution of Angola provides for freedom of religion, and the Government generally respects this right in practice. There were no reports of societal abuses or discrimination based on religious belief or practice. Christianity is the religion of the vast majority of the population, with Catholicism as the largest single religious group. The Catholic Church estimates that 55 percent of the population is Catholic. There is also a small Muslim community, estimated at 80-90,000 adherents, composed largely of migrants from West Africa and families of Lebanese extraction. There are few declared atheists in the country. Traditional African religions are adhered to by a few peripheral rural societies only, but some traditional beliefs are held by many people.[2]

Members of the clergy regularly use their pulpits to criticize government policies, though church leaders report self-censorship regarding particularly sensitive issues. The Government banned 17 religious groups in Cabinda on charges of practicing harmful exorcism rituals on adults and children accused of "witchcraft," illegally holding religious services in residences, and not being registered. Although the law does not recognize the existence of witchcraft, abusive actions committed while practicing a religion are illegal. Members of these groups were not harassed, but two leaders were convicted in 2006 of child abuse and sentenced to 8 years' imprisonment.[2]

Egypt

Constitutionally, freedom of belief is "absolute" and the practice of religious rites is provided in Egypt, but the government has historically persecuted its Coptic minority and unrecognized religions.[3] Islam is the official state religion, and Shari'a is the primary source of all new legislation.[4] Egypt's population is majority Sunni Muslims. Shi'a Muslims constitute less than 1 percent of the population.[5] Estimates of the percentage of Christians range from 10 to 20 percent.[5]

Treatment of Coptic Christians

Coptic Christians, an ethnoreligious group indigenous to Egypt, face discrimination at multiple levels of the government, ranging from a disproportional representation in government ministries to laws that limit their ability to build or repair churches. Coptic Christians are minimally represented in law enforcement, state security, and public office, and are discriminated against in the workforce on the basis of their religion. In 2009, The Pew Forum ranked Egypt among the 12 worst countries in the world in terms of religious violence against religious minorities and in terms of social hostilities against Christians.[6]

Treatment of Ahmadiyya Muslims

The Ahmadiyya movement in Egypt, which numbers up to 50,000 adherents in the country,[7] was established in 1922[8] but has seen an increase in hostility and government repression as of the 21st century. The Al-Azhar University has denounced the Ahmadis[9] and Ahmadis have been hounded by police along with other Muslim groups deemed to be deviant under Egypt's defamation laws.[10][11]

Treatment of Bahái

Egypt's government-issued ID cards have historically declared the holder's religion, but only the religions of Islam, Christianity, and Judaism were considered valid options by the government. As an unrecognized religious group that faced explicit government persecution for much of the 20th century, members of the Bahá'í Faith in Egypt (est. pop 2,000[12]) historically would rely on sympathetic government clerks to get their ID cards marked with either a dash, "other", or Bahái.[13]

As Egypt adopted an electronic ID system in the 1990s, Electronic processing locked out the possibility of an unlisted religion, or any religious affiliation other than Muslim, Christian, or Jewish. Consequently, adherents of any other faith (or no faith) became unable to obtain any government identification documents (such as national identification cards, birth certificates, death certificates, marriage or divorce certificates, or passports) necessary to exercise their rights in their country unless they lied about their religion. Bahá'ís became virtual non-citizens, without access to employment, education, and all government services, including hospital care.[14]

In a series of court cases from 2006 to 2008, judges ruled that the government should issue ID cards with a dash instead of religious affiliation for Bahái citizens.[15] The issue is presumed to have been resolved as of 2009.[15]

Treatment of atheists

There are Egyptians who identify themselves as atheist and agnostic. It is however difficult to quantify their number as the stigma attached to being one makes it hard for irreligious Egyptians to publicly profess their views.[16][17] Furthermore, public statements that can be deemed critical of Islam or Christianity can be tried under the country's notorious blasphemy law. Outspoken atheists, like Alber Saber, have been convicted under this law.

The number of atheists is reportedly on the rise among the country's youth, many of whom organize and communicate with each other on the internet.[18][19] In 2013 an Egyptian newspaper reported that 3 million out of 84 million Egyptians are atheists.[20] While the government has acknowledged this trend, it has dealt with it as a problem that needs to be confronted, comparing it to religious extremism.[21] Despite hostile sentiments towards them atheists in Egypt have become increasingly vocal on internet platforms like YouTube and Facebook since the Egyptian revolution of 2011, with some videos discussing atheist ideas receiving millions of views.[22]

In a 2011 Pew Research poll of 1,798 Muslims in Egypt, 63% of those surveyed supported "the death penalty for people who leave the Muslim religion."[23] However, no such punishment actually exists in the country.[24] In January 2018 the head of the parliament's religious committee, Amr Hamroush, suggested a bill to make atheism illegal, stating that "it [atheism] must be criminalised and categorised as contempt of religion because atheists have no doctrine and try to insult the Abrahamic religions".[25]

Atheists or irreligious people cannot change their official religious status, thus statistically they are counted as followers of the religion they were born with.[19]

Mauritania

Freedom of religion in Mauritania is limited by the Government. The constitution establishes the country as an Islamic republic and decrees that Islam is the religion of its citizens and the State. In April 2018, the National Assembly passed a law making the death penalty mandatory for "blasphemy".

Non-Muslim resident expatriates and a few non-Muslim citizens practice their religion openly with certain limitations against proselytizing to Muslims and transmitting religious materials. Almost all of the population are practicing Sunni Muslims, although there are a few non-Muslims. Roman Catholic and non-denominational Christian churches have been established in Nouakchott, Atar, Zouerate, Nouadhibou, and Rosso. A number of expatriates practice Judaism but there are no synagogues.

Relations between the Muslim community and the small non-Muslim community are generally amicable. There are several foreign faith-based nongovernmental organizations (NGO's) active in humanitarian and developmental work in the country.

The Government does not register religious groups; however, secular NGOs, inclusive of humanitarian and development NGO's affiliated with religious groups, must register with the Ministry of the Interior.[26]

Nigeria

Nigeria is nearly equally divided between Christianity and Islam, though the exact ratio is uncertain. There is also a growing population of non-religious Nigerians who accounted for the remaining 5 percent. The majority of Nigerian Muslims are Sunni and are concentrated in the northern region of the country, while Christians dominate in the south.

Nigeria allows freedom of religion.[27] Islam and Christianity are the two major religions.[28] 12 states in Nigeria use a sharia-based penal code, which can include penalties for apostasy. Religious persecution is largely carried out by groups not affiliated with the Nigerian government, such as Boko Haram.[29] There is a great stigma attached to being an atheist.[30][31]

South Africa

South Africa is a secular democracy with freedom of religion guaranteed by its constitution.[32] Pursuant to Section 9 of the Constitution, the Equality Act of 2000 prohibits unfair discrimination on various grounds including religion.[33][34] The Equality Act does not apply to unfair discrimination in the workplace, which is covered by the Employment Equity Act.[35]

The Witchcraft Suppression Act of 1957 based on colonial witchcraft legislation criminalises claiming a knowledge of witchcraft, conducting specified practices associated with witchcraft including the use of charms and divination, and accusing others of practising witchcraft.[36] In 2007 the South African Law Reform Commission received submissions from the South African Pagan Rights Alliance and the Traditional Healers Organisation requesting the investigation of the constitutionality of the act and on 23 March 2010 the Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development approved a South African Law Reform Commission project to review witchcraft legislation.[37][38]

Sudan

Although the 2005 Interim National Constitution (INC) of Sudan provides for freedom of religion throughout the entire country of Sudan, the INC enshrines Shari'a as a source of legislation in the country and the official laws and policies of the government systematically favor Islam.

Discrimination based on religious affiliation, belief, or practice, and religious prejudice remains widespread. Muslims who express an interest in Christianity, or convert to Christianity, face strong social pressure to recant. Muslims who convert to Christianity can face the death penalty for apostasy.

Mariam Yahia Ibrahim Ishag

In May 2014, a woman called Maryam Yaḥyā Ibrahīm Isḥaq was sentenced to a hundred lashes for adultery and to death for apostasy. Her mother raised her a Christian since her Muslim father was absent, but the Sudanese legal system considers her a Muslim. Isḥaq was sentenced to a hundred lashes for adultery because she married a Christian man from South Sudan, while Muslim law considers her a Muslim and the marriage invalid. When Isḥaq argued she was a Christian, she was sentenced to death for apostasy.

The verdict breaches the Sudanese constitution and commitments based on regional and international law. Western embassies, Amnesty International and other human rights groups protested that Ishaq should be able to choose her religion and should be released.[39] She was later released and after further delays left Sudan.[40]

South Sudan

The constitution of Southern Sudan provides for freedom of religion, and other laws and policies of the Government of South Sudan contribute to the generally free practice of religion.[41]

The Pew Research Center on Religion and Public Life report from December 2012 estimated that in 2010, there were 6.010 million Christians (60.46%), 3.270 million followers of African Traditional Religion (32.9%), 610,000 Muslims (6.2%) and 50,000 unaffiliated (no known religion) of a total 9,940,000 people in South Sudan.[42]

Asia

Afghanistan

Afghanistan is an Islamic republic where Islam is practiced by 99.7% of its population. Roughly 90% of the Afghans follow Sunni Islam, with the rest practicing Shia Islam.[43][44] Apart from Muslims, there are also small minorities of Sikhs and Hindus.[45][46]

The Constitution of Afghanistan established on January 23, 2004 mandates that:

- Afghanistan shall be an Islamic Republic, independent, unitary, and an indivisible state.

- The sacred religion of Islam shall be the religion of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. Followers of other faiths shall be free within the bounds of law in the exercise and performance of their religious rights.

- No law shall contravene the tenets and provisions of the holy religion of Islam in Afghanistan.

In practice, the constitution limits the political rights of Afghanistan's non-Muslims, and only Muslims are allowed to become the President.[47]

In March 2015, a 27-year-old Afghan woman was murdered by a mob in Kabul over false allegations of burning a copy of the Koran.[48] After beating and kicking Farkhunda, the mob threw her over a bridge, set her body on fire and threw it in the river.[49]

Taliban controlled regions

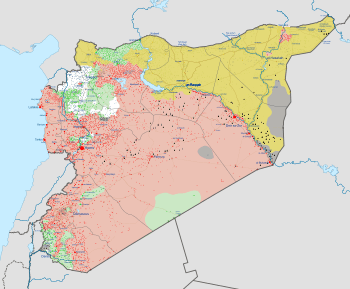

.svg.png)

Historically, the Taliban, which controlled Afghanistan from 1996 to 2001, prohibited free speech about religious issues or discussions that challenge orthodox Sunni Muslim views. Repression by the Taliban of the Hazara ethnic group, which is predominantly Shia Muslim, was particularly severe. Although the conflict between the Hazaras and the Taliban was political and military as well as religious, and it is not possible to state with certainty that the Taliban engaged in its campaign against the Shi'a solely because of their religious beliefs, the religious affiliation of the Hazaras apparently was a significant factor leading to their repression. After the United States invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, the Taliban was forced out of power and began an insurgency against the new government and allied US forces. The Taliban continues to prohibit music, movies, and television on religious grounds in areas that it still holds.[50]

According to the U.S. Military, the Taliban controls 10% of Afghanistan as of December 2017.[51] There are also pockets of territory controlled by Islamic State affiliates. On October 14, 2017, The Guardian reported that there were then between 600 and 800 ISIL-KP militants left in Afghanistan, who are mostly concentrated in Nangarhar Province.[52]

Armenia

As of 2011, most Armenians are Christians(94.8%)and members of Armenia's own church, the Armenian Apostolic Church.[53]

The Constitution of Armenia as amended in December 2005 provides for freedom of religion; however, the law places some restrictions on the religious freedom of adherents of minority religious groups, and there were some restrictions in practice. The Armenian Apostolic Church which has formal legal status as the national church, enjoys some privileges not available to other religious groups. Some denominations reported occasional discrimination by mid- or low-level government officials but found high-level officials to be tolerant. Societal attitudes toward some minority religious groups were ambivalent, and there were reports of societal discrimination directed against members of these groups.

The law does not mandate registration of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), including religious groups; however, only registered organizations have legal status. Only registered groups may publish newspapers or magazines, rent meeting places, broadcast programs on television or radio, or officially sponsor the visas of visitors, although there is no prohibition on individual members doing so. There were no reports of the Government refusing registration to religious groups that qualified for registration under the law. To qualify for registration, religious organizations must "be free from materialism and of a purely spiritual nature," and must subscribe to a doctrine based on "historically recognized holy scriptures." The Office of the State Registrar registers religious entities. The Department of Religious Affairs and National Minorities oversees religious affairs and performs a consultative role in the registration process. A religious organization must have at least 200 adult members to register.

The Law on Freedom of Conscience prohibits "proselytizing" but does not define it. The prohibition applies to all groups, including the Armenian Church. Most registered religious groups reported no serious legal impediments to their activities.[54]

Azerbaijan

The Constitution of Azerbaijan provides that persons of all faiths may choose and practice their religion without restriction, although, some sources state that there have been some abuses and restrictions. Azerbaijan is a majority Muslim country. Various estimates calculate that upwards of 95% of the population identify as Muslim.[55][56][57] Most are adherents of Shia branch with a minority (15%) being Sunni Muslim, although differences traditionally have not been defined sharply.[56] For many Azerbaijanis, Islam tends toward a more ethnic/nationalistic identity than a purely religious one.[58]

Religious groups are required by law to register with the State Committee on Religious Associations of the Republic of Azerbaijan.[59] Organizations which fail to register may be considered illegal and may be forbidden to operate within Azerbaijan.[60] Some religious groups reported delays in and denials of their registration attempts. There are limitations upon the ability of groups to import religious literature.[61] Most religious groups met without government interference; however, local authorities monitored religious services, and officials at times harassed and detained members of "nontraditional" religious groups. There were some reports of societal abuses or discrimination based on religious belief or practice. The US. State Department reported prejudice against Muslims who convert to other faiths and hostility toward groups that proselytize, particularly evangelical Christian and other missionary groups, as well as Iranian groups and Salafists, who are seen as a threat to security.[61]

Bangladesh

Bangladesh was founded as a secular state, but Islam was made the state religion in the 1980s. However, in 2010, the High Court held up the secular principles of the 1972 constitution.[62] The Constitution of Bangladesh establishes Islam as the state religion but also allows other religions to be practiced in harmony.[63]

While the government of Bangladesh does not interfere in the free practice of religion by people within its borders, incidences of individual violence against minority groups are common. In particular, Chakma Buddhists, Hindus, Christians, and Ahmadiyya Muslims are subject to persecution.[64][65][66] Additionally, atheists face persecution, with prominent bloggers having been assassinated by radical groups, such as the Ansarullah Bangla Team.[67]

Cambodia

Article 43 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Cambodia reads: "Khmer citizens of either sex shall have the right to freedom of belief. Freedom of religious belief and worship shall be guaranteed by the State on the condition that such freedom does not affect other religious beliefs or violate public order and security. Buddhism shall be the State religion."[68]

China

The Constitution of the People's Republic of China provides for freedom of religious belief; however, the government restricts religious practice to government-sanctioned organizations and registered places of worship and controls the growth and scope of the activity of religious groups.[69] The government of China currently recognizes five religious groups: the Buddhist Association of China, the Chinese Taoist Association, the Islamic Association of China, the Three-Self Patriotic Movement (a Protestant group), and the Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association.

Members of the governing Communist Party are strongly discouraged from holding religious faith.[70]

A significant number of non-sanctioned churches and temples exist, attended by locals and foreigners alike. Unregistered or underground churches are not officially banned, but are not permitted to openly conduct religious services. These bodies may face varying degrees of interference, harassment, and persecution by state and party organs. In some instances, unregistered religious believers and leaders have been charged with "illegal religious activities" or "disrupting social stability."[71] Religious believers have also been charged under article 300 of the criminal code, which forbids using heretical organizations to "undermine the implementation of the law."[72]

Falun Gong

Following a period of meteoric growth of Falun Gong in the 1990s, the Communist Party launched a campaign to "eradicate" Falun Gong on 20 July 1999. The suppression is characterised by multifaceted propaganda campaign, a program of enforced ideological conversion and re-education, and a variety of extralegal coercive measures such as arbitrary arrests, forced labor, and physical torture, sometimes resulting in death.[73]

An extra-constitutional body called the 6-10 Office was created to lead the suppression of Falun Gong.[74] The authorities mobilized the state media apparatus, judiciary, police, army, the education system, families and workplaces against the group.[75] The campaign is driven by large-scale propaganda through television, newspaper, radio and internet.[76] There are reports of systematic torture,[77][78] illegal imprisonment, forced labor, organ harvesting[79] and abusive psychiatric measures, with the apparent aim of forcing practitioners to recant their belief in Falun Gong.[80]

Tibetan Buddhism

Prior to Tibet's incorporation into China, Tibet was a theocracy with the Dalai Lama functioning as the head of government.[81] Since incorporation into China, Dalai Lama have at times sanctioned Chinese control of the territory,[82] while at other times they have been a focal point of political and spiritual opposition to the Chinese government.[83] As various high-ranking Lamas in the country have died, the Chinese government has proposed their own candidates for these positions, which has led at times to rival claimants to the same position. In an effort to further control Tibetan Buddhism and thus Tibet, the Chinese government passed a law in 2007 requiring a Reincarnation Application be completed and approved for all lamas wishing to reincarnate.[84]

Treatment of Muslims

Ethnicity plays a large role in the Chinese government's attitude toward Muslim worship. Authorities in Xinjiang impose strict restrictions on Uyghur Muslims: mosques are monitored by the government, Ramadan observance is restricted, and the government has run campaigns to discourage men from growing beards which are associated with fundamentalist Islam.[85] Individual Uyghur Muslims have been detained for practicing their religion.[71] However, this persecution is largely due to the association of Islam with Uyghur separatism. Hui Muslims living in China do not face the same degree of persecution, and the government has at times been particularly lenient toward Hui practitioners. Although religious education for children is officially forbidden by law in China, the Communist party allows Hui Muslims to violate this law and have their children educated in religion and attend Mosques while the law is enforced on Uyghurs. After secondary education is completed, China then allows Hui students who are willing to embark on religious studies under an Imam.[86] China does not enforce the law against children attending Mosques on non-Uyghurs in areas outside of Xinjiang.[87][88]

Support for traditional religions

Toward the end of the 20th century, China's government began to more openly encourage the practice of various traditional cults, particularly the state cults devoted to the Yellow Emperor and the Red Emperor. In the early 2000s, the Chinese government became open especially to traditional religions such as Mahayana Buddhism, Taoism and folk religion, emphasising the role of religion in building a "Harmonious Society" (hexie shehui),[89] a Confucian idea.[90][91] Aligning with Chinese anthropologists' emphasis on "religious culture",[92] the government considers these religions as integral expressions of national "Chinese culture" and part of China's intangible cultural heritage.[92][93]

Cyprus

The Republic of Cyprus largely upholds and respects religious freedom within its territory. However, individual cases of religious discrimination against Muslims have occurred.[94] In 2016, a 19th-century mosque was attacked by arsonists, an action condemned by the government.[95][96]

In 2018, the Cyprus Humanist Association accused the Ministry of Education of promoting anti-atheist educational content on its government website.[97]

Northern Cyprus

While freedom of religion is constitutionally protected in Turkish occupied Northern Cyprus, the government has at times restricted the practice of Greek Orthodox Churches. A controversial 2016 decision restricts most Orthodox churches to celebrate a single religious service per year.[98][99]

India

The Indian constitution's preamble states that India is a secular state. Freedom of religion is a fundamental right guaranteed by the constitution. According to Article 25 of the Indian Constitution, every citizen of India has the right to "profess, practice and propagate religion", "subject to public order, morality and health" and also subject to other provisions under that article.[100]

Article 25 (2b) uses the term "Hindus" for all classes and sections of Hindus, Jains, Buddhists and Sikhs.[101] Sikhs and Buddhists objected to this wording that makes many Hindu personal laws applicable to them.[101] However, the same article also guarantees the right of members of the Sikh faith to bear a Kirpan.[102]

Religions require no registration. The government can ban a religious organisation if it disrupts communal harmony, has been involved in terrorism or sedition, or has violated the Foreign Contributions Act. The government limits the entry of any foreign religious institution or missionary and since the 1960s, no new foreign missionaries have been accepted though long term established ones may renew their visas.[103] Many sections of the law prohibit hate speech and provide penalties for writings, illustrations, or speech that insult a particular community or religion.

Some major religious holidays like Diwali (Hindu), Christmas (Christian), Eid (Muslim) and Guru Nanak's birth anniversary (Sikh) are considered national holidays. Private schools offering religious instruction are permitted while government schools are non-religious.[104]

The government has set up the Ministry of Minority Affairs, the National Human Rights Commission(NHRC) and the National Commission for Minorities(NCM) to investigate religious discrimination and to make recommendations for redressal to the local authorities. Though they do not have any power, local and central authorities generally follow them. These organisations have investigated numerous instances of religious tension including the implementation of "anti-conversion" bills in numerous states, the 2002 Gujarat violence against Muslims and the 2008 attacks against Christians in Orissa.[105]

Jammu and Kashmir

The Grand Ashura Procession In Kashmir where Shia Muslims mourn the death of Husayn ibn Ali has been banned by the Government of Jammu and Kashmir since the 1990s. People taking part in it are detained, and injured[106] by Jammu and Kashmir Police every year.[107] According to the government, this restriction was placed due to security reasons.[107] Local religious authorities and separatist groups condemned this action and said it is a violation of their fundamental religious rights.[108]

Indonesia

The Indonesian Constitution states "every person shall be free to choose and to practice the religion of his/her choice" and "guarantees all persons the freedom of worship, each according to his/her own religion or belief".[109] It also states that "the nation is based upon belief in one supreme God." The first tenet of the country's national ideology, Pancasila, similarly declares belief in one God. Government employees are required to swear allegiance to the nation and to the Pancasila ideology. While there are no official laws against atheism, a lack of religious belief is contrary to the first tenet of Pancasila, and atheists have been charged and prosecuted for blasphemy.[110][111] Other laws and policies at the national and regional levels restrict certain types of religious activity, particularly among unrecognized religious groups and "deviant" sects of recognized religious groups.[112]

The government officially only recognises six religions, namely Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism and Confucianism.[113][114]

Iran

The Iranian constitution was drafted during the Iranian Constitutional Revolution in 1906;[115] While the constitution was modelled on Belgium's 1831 constitution, the provisions guaranteeing freedom of worship were omitted.[116] Subsequent legislation provided some recognition to the religious minorities of Zoroastrians, Jews and Christians, in addition to majority Muslim population, as equal citizens under state law, but it did not guarantee freedom of religion and "gave unprecedented institutional powers to the clerical establishment."[116] The Islamic Republic of Iran, that was established after the Iranian revolution, recognizes four religions, whose status is formally protected: Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.[117] Members of the first three groups receive special treatment under law, and five of the 270 seats in parliament are reserved for members of these religious groups.[118][119] However, senior government posts including the presidency are reserved exclusively for followers of Shia Islam.[120]

Additionally, adherents of the Bahá'í Faith, Iran's largest religious minority, are not recognized and are persecuted. Bahá'ís have been subjected to unwarranted arrests, false imprisonment, executions, confiscation and destruction of property owned by individuals and the Bahá'í community, denial of civil rights and liberties, and denial of access to higher education.[117] Since the Islamic Revolution of 1979, Iranian Bahá'ís have regularly had their homes ransacked or been banned from attending university or holding government jobs, and several hundred have received prison sentences for their religious beliefs.[117] Bahá'í cemeteries have been desecrated and property seized and occasionally demolished, including the House of Mírzá Buzurg, Bahá'u'lláh's father.[121] The House of the Báb in Shiraz has been destroyed twice, and is one of three sites to which Bahá'ís perform pilgrimage.[121][122][123]

Iraq

Iraq is a constitutional democracy with a republican, federal, pluralistic system of government, consisting of 18 provinces or "governorates." Although the Constitution recognizes Islam as the official religion and states that no law may be enacted that contradicts the established provisions of Islam, it also guarantees freedom of thought, conscience, and religious belief and practice.

While the Government generally endorses these rights, political instability during the Iraq War and the ongoing Iraqi Civil War have prevented effective governance in parts of the country not controlled by the Government, and the Government's ability to protect religious freedoms has been handicapped by insurgency, terrorism, and sectarian violence.

Since 2003, when the government of Saddam Hussein fell, the Iraqi government has generally not engaged in state-sponsored persecution of any religious group, calling instead for tolerance and acceptance of all religious minorities. However, some government institutions have continued their long-standing discriminatory practices against the Baha'i and Sunni Muslims.

Uprisings of the Islamic State (IS), formerly called the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) or the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), have led to violations of religious freedom in certain parts of Iraq. IS is a Sunni jihadist group that claims religious authority over all Muslims across the world[124] and aspires to bring most of the Muslim-inhabited regions of the world under its political control beginning with Iraq.[125] ISIS follows an extreme anti-Western interpretation of Islam, promotes religious violence and regards those who do not agree with its interpretations as infidels or apostates. Concurrently, IS aims to establish a Salafist-orientated Islamist state in Iraq, Syria and other parts of the Levant.[126]

Israel

Israel's Basic Law of Human Dignity and Liberty promises freedom and full social and political equality, regardless of political affiliation, while also describing the country as a "Jewish and democratic state".[127] However, the Pew Research Center has identified Israel as one of the countries that places high restrictions on religion,[128] and the U.S. State Department notes that while the government generally respects religious freedom in practice, governmental and legal discrimination against non-Jews non-Orthodox Jews exist, including arrests, detentions, and the preferential funding of Jewish schools and religious organizations over similar organizations serving other religious groups.[127] On July 18, 2018, Israel adopted a law defining itself as "the homeland of the Jewish people in which the Jewish people fulfill their self-determination according to their cultural and historical legacy."

Various observers have objected that archaeological and construction practices funded by the Israeli government are used to bolster Jewish claims to the land while ignoring other sites of archaeological importance,[129][130] some going as far as to claim that Israel systematically disrespected sites of Christian and Muslim cultural and historical importance.[131]

Several influential political parties within Israel's Knesset have explicitly religious character and politics (Shas, The Jewish Home, United Torah Judaism). Shas and United Torah Judaism represent different ethnic subgroups of the Haredi Jewish community in Israel.[132] These parties seek to strengthen Jewish religious laws in the country and enforce more ultra-orthodox customs on the rest of the population, among other political platforms specific to their voterbase.Historically the state's treatment of Haredi Jewish communities has been an issue of political contention, and different Haredi communities are divided on their attitude toward the Israeli state itself. The Jewish Home represents the religious right-wing Israeli settler communities in the West Bank.

While Israel's legal tradition is based on English Common Law, not Jewish Halakha, Halakha is applied in many civil matters, such as laws relating to marriage and divorce, and legal rulings concerning the Temple Mount. Israeli authorities have codified a number of religious laws in the country's political laws, including an official ban on commerce on Shabbat[133] and a 1998 ban on the importation of nonkosher meat.[134]

Law of Return

The Israeli Law of Return provides that any Jew, or the child or grandchild of a Jew, may immigrate to Israel with their spouse and children. Israel's process for determining the validity of a prospective immigrant's claim to Judaism has changed over time, and has been subject to various controversies.[127][135]

Management of holy sites

Israel's 1967 Protection of Holy Sites Law protects the holy sites of all religious groups in the country. The government also provides for the maintenance and upkeep of holy sites, although The U.S. State Department has noted that Jewish sites receive considerably more funding than Muslim sites, and that the government additionally provides for the construction of new Jewish synagogues and cemeteries.[127]

Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif and Al-Aqsa Mosque

The government of Israel has repeatedly upheld a policy of not allowing non-Muslims to pray at the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif since their annexation of East Jerusalem and the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif site in 1967. The government has ruled to allow access to the compound for individuals regardless of faith, but removes non-Muslims if they appear to be praying and sometimes restricts access for non-Muslims and young Muslim men, citing security concerns. Since 2000, the Jerusalem Islamic Waqf that manages the site and the Al-Aqsa Mosque has restricted non-Muslims from entering the Dome of the Rock shrine and Al-Aqsa, and prohibits wearing or displaying non-Muslim religious symbols.[127]

Western Wall

The religious practices allowed at the Western Wall are established by the Rabbi of the Western Wall, appointed jointly by the Prime Minister of Israel and chief rabbis. Mixed-gender prayer is forbidden at the Western Wall, in deference to Orthodox Jewish practice. Women are not allowed to wear certain prayer shawls, and are not allowed to read aloud from the Torah at the Wall.[127]

In the Palestinian Territories

The West Bank

In the West Bank, Israel and the Palestinian National Authority (PA) enforce varying aspects of religious freedom. The laws of both Israel and the Palestinian National Authority protect religious freedom, and generally enforce these protections in practice. The PA enforces the Palestinian Basic Law, which provides for the freedom of religion, belief, and practice within the territories it administers. It also holds that Islam is the official religion of the Palestinian Territories, and that legislation should be based on interpretations of Islamic Law. Six seats in the 132-member Palestinian Legislative Council are reserved for Christians, while no other religious guarantees or restrictions are enforced. The PA recognizes a Friday-Saturday weekend, but allows Christians to work on Saturday in exchange for a day off on Sunday. Heightened tensions exist between Jewish and non-Jewish residents of this territory, although relations between other religious groups are relatively cordial.[129]

The Palestinian Authority provides funding for Muslim and Christian holy sites in the West Bank and has been noted to give preferential treatment to Muslim sites, while the Israeli Government funds Jewish sites. Matters of inheritance, marriage, and dowry are handled by religious courts of the appropriate religion for the people in question, with members of faiths unrecognized by the PA are often advised to go abroad to resolve their affairs. Religious education is mandatory for grades 1 through 6 in schools funded by the PA, with separate courses available for Muslims and Christians.[129]

While it is not strictly a religious ban, Israeli policies restricting the freedom of movement of Palestinians throughout the West Bank and between the West Bank and Israel restrict the ability for Palestinians to visit certain religious sites, such as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the Al-Aqsa Mosque, and the Church of the Nativity. These restrictions are sometimes relaxed for portions of the population on specific holidays. Christian groups have complained that an extended visa application process for the West Bank has impeded their ability to operate there. Jews are routinely provided access to specific holy sites in territories under the control of the PA, and holy sites such as the that are significant to both Jews and Muslims, Cave of the Patriarchs, enforce restricted access to either group on different days, with Jews often facing less restricted access and lighter security screening.[129]

Gaza Strip

Despite nominally being a part of the territory administered by the Palestinian National Authority, the Gaza Strip has been de facto controlled by Hamas since the 2006 Palestinian civil skirmishes. Religious freedom in Gaza is curtailed by Hamas, which imposes a stricter interpretation of Islamic law and at times has broadcast explicitly anti-Jewish propaganda. Due to the blockade of the Gaza Strip, Muslim residents of Gaza are not allowed by the Israeli government to visit holy sites in Israel or the West Bank, and Christian clergy from outside Gaza are not allowed access to the region. However, some Christian residents of Gaza have been issued permits by Israel to enter Israel and the West Bank during Christmas to visit family and holy sites.[129]

Hamas largely tolerates the Christian population of the Gaza Strip and does not force Christians to follow Islamic law. However, Christians at times face harassment, and there are concerns that Hamas does not sufficiently protect them from religiously motivated violence perpetrated by other groups in the Gaza Strip.[129]

Japan

Historically, Japan had a long tradition of mixed religious practice between Shinto and Buddhism since the introduction of Buddhism in the 7th century. Though the Emperor of Japan is supposed to be the direct descendant of Amaterasu Ōmikami, the Shinto sun goddess, all Imperial family members, as well as almost all Japanese, were Buddhists who also practiced Shinto religious rites as well. Christianity flourished when it was first introduced by Francis Xavier, but was soon violently suppressed.

After the Meiji Restoration, Japan tried to reform its state to resemble a European constitutional monarchy. The Emperor, Buddhism, and Shintoism were officially separated and Shintoism was set as the state religion. The Constitution specifically stated that Emperor is "holy and inviolable" (Japanese: 天皇は神聖にして侵すべからず, translit. tennou wa shinsei nishite okasu bekarazu). During the period of Hirohito, the status of emperor was further elevated to be a living god (Japanese: 現人神, translit. Arahito gami). This ceased at the end of World War II, when the current constitution was drafted. (See Ningen-sengen.)

In 1946, during the Occupation of Japan, the United States drafted Article 20 of the constitution of Japan (still in use), which mandates a separation of religious organizations from the state, as well as ensuring religious freedom: "No religious organization shall receive any privileges from the State, nor exercise any political authority. No person shall be compelled to take part in any religious act, celebration, rite or practice. The State and its organs shall refrain from religious education or any other religious activity."

The New Komeito Party is a political party associated with the religion Sōka Gakkai, a minor religion in Japan.

Jordan

The Constitution of Jordan provides for the freedom to practice the rights of one's religion and faith in accordance with the customs that are observed in the kingdom, unless they violate public order or morality. The state religion is Islam. The Government prohibits conversion from Islam and proselytizing to Muslims.[136]

Members of unrecognized religious groups and converts from Islam face legal discrimination and bureaucratic difficulties in personal status cases. Converts from Islam additionally risk the loss of civil rights. Shari'a courts have the authority to prosecute proselytizers.[136]

Relations between Muslims and Christians generally are good; however, adherents of unrecognized religions and Muslims who convert to other faiths face societal discrimination. Prominent societal leaders have taken steps to promote religious freedom.[136]

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan has a long tradition of secularism and tolerance. In particular, Muslim, Russian Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Jewish leaders all reported high levels of acceptance in society.[137] The Constitution of Kazakhstan provides for freedom of religion, and the various religious communities worship largely without government interference. However, local officials attempt on occasion to limit the practice of religion by some nontraditional groups, and higher-level officials or courts occasionally intervene to correct such attempts.[137]

As of 2007, the law on religion continues to impose mandatory registration requirements on missionaries and religious organizations. Most religious groups, including those of minority and nontraditional denominations, reported that the religion laws did not materially affect religious activities. In 2007, the Hare Krishna movement, a registered group, suffered the demolition of 25 homes as part of the Karasai local government's campaign to seize title to its land based on alleged violations of property laws.[137][138]

North Korea

The North Korean constitution guarantees freedom of belief; however, the US Department of State International Religious Freedom Report for 2011 claims that "Genuine religious freedom does not exist."[139]

While many Christians in North Korea fled to the South during the Korean War, and former North Korean president Kim Il-sung criticized religion in his writings, it is unclear the extent to which religious persecution was enacted, as narratives about persecution faced by Christians are complicated by evidence of pro-Communist Christian communities that may have existed since at least the 1960s, and that many Christian defectors from North Korea were also of a high socioeconomic class and thus would have had other reasons to oppose and face persecution from the government.[140] The Federation of Korean Christians and Korea Buddhist Federation[141] are the official representatives of those faith groups in government, but it is unclear to what extent they are actually representative of religious practitioners in the country.

South Korea

According to the US Department of State, As of 2012, the constitution provides for freedom of religion, and the government generally respected this right in practice.[142][143]

In the Pew Research Center's Government Restrictions Index 2015 index the country was categorized as having moderate levels of government restrictions on the freedom of religion, up from previous categorizations of low levels of government restrictions.[144]

Since the 1980s and the 1990s there have been acts of hostility committed by Protestants against Buddhists and followers of traditional religions in South Korea. This include the arson of temples, the beheading of statues of Buddha and bodhisattvas, and red Christian crosses painted on either statues or other Buddhist and other religions' properties.[145] Some of these acts have even been promoted by churches' pastors.[145]

In 2018, a mass protest broke out in support of freedom of religion and against the government's inaction on widespread programs of violent forced conversion carried out by Christian churches under the guide of the Christian Council of Korea (CCK), just after a woman named Ji-In Gu, one among approximately a thousand victims of the churches, was kidnapped and killed while being forced to convert. Before being killed, Ji-In Gu dedicated herself in exposing the conversion treatments, and for such reason she had become a target of the Christian churches.[146][147]

Kyrgyzstan

The Constitution of Kyrgyzstan provides for the freedom of religion in Kyrgyzstan, and the government generally respects this right in practice. However, the Government restricts the activities of radical Islamic groups that it considered threats to stability and security and hampered or refused the registration of some Christian churches. The Constitution provides for the separation of religion and state, and it prohibits discrimination based on religion or religious beliefs. The Government does not officially support any religion; however, a May 6, 2006 decree recognized Islam (practiced by 88% of the population)[148] and Russian Orthodoxy (practiced by 9.4% of the population)[148] as traditional religious groups.

The State Agency for Religious Affairs (SARA), formerly called the State Commission on Religious Affairs (SCRA), is responsible for promoting religious tolerance, protecting freedom of conscience, and overseeing laws on religion. All religious organizations, including schools, must apply for approval of registration from SARA. The Muftiate (or Spiritual Administration of Muslims of Kyrgyzstan-SAMK) is the highest Islamic managing body in the country. The Muftiate oversees all Islamic entities, including institutes and madrassahs, mosques, and Islamic organizations.[148]

Although most religious groups and sects operated with little interference from the Government or each other, there have been several cases of societal abuse based on religious beliefs and practices. Muslims who attempt to convert to other religions face heavy censure and persecution. In one case, a mob upset at a Baptist pastor's conversions of Muslims to Christianity publicly beat the pastor and burned his Bibles and religious literature.[148]

Laos

The Constitution of Laos provides for freedom of religion, some incidents of the persecution of Protestants have been reported. The Lao Front for National Construction (LFNC), a popular front organization for the Lao People's Revolutionary Party (LPRP), is responsible for the oversight of religious practice. The Prime Minister's Decree on Religious Practice (Decree 92) was the principal legal document defining rules for religious practice.[149]

Local officialshave pressured minority Protestants to renounce their faith on threat of arrest or forceful eviction from their villages. Such cases occurred in Bolikhamsai, Houaphanh Province, and Luang Namtha provinces. Arrests and detentions of Protestants occurred in Luang Namtha, Oudomxay, Salavan, Savannakhet, and Vientiane provinces. Two Buddhist monks were arrested in Bolikhamsai Province for having been ordained without government authorization. In some areas, minority Protestants were forbidden from gathering to worship. In areas where Protestants were actively proselytizing, local officials sometimes subjected them to "reeducation."[149]

Conflicts between ethnic groups and movement among villages sometimes exacerbated religious tensions. The efforts of some Protestant congregations to establish churches independent of the Lao Evangelical Church (LEC) continued to cause strains within the Protestant community.[149]

Lebanon

The Constitution of Lebanon provides for freedom of religion and the freedom to practice all religious rites provided that the public order is not disturbed. The Constitution declares equality of rights and duties for all citizens without discrimination or preference but establishes a balance of power among the major religious groups through a confessionalist system, largely codified by the National Pact. Family matters such as marriage, divorce and inheritance are still handled by the religious authorities representing a person's faith. Calls for civil marriage are unanimously rejected by the religious authorities but civil marriages conducted in another country are recognized by Lebanese civil authorities.[150]

National Pact

The National Pact is an agreement that specifies that specific government positions must go to members of specific religious groups, splitting power between the Maronite Christians, Greek Orthodox Christians, Sunni Muslims, Shia Muslims, and Druze, as well as stipulating some positions for the country's foreign policy. The first version of the pact, established in 1943, gave Christians a guaranteed majority in Parliament,[151] reflecting the population of the country at the time, and specified that the highest office, the President of Lebanon, must be held by a Maronite Christian.[152] Over the following decades, sectarian unrest would increase due to dissatisfaction with the greater power given to the Christian population and the refusal of the government to take another census that would provide the basis for a renegotiation of the National Pact eventually led to the Lebanese Civil War in 1975.[152] The National Pact was renegotiated as part of the Taif Agreement to end the civil war, with the new conditions guaranteeing parliamentary parity between Muslim and Christian populations and reducing the power of the position of the Maronite President of Lebanon relative to the Sunni Prime Minister of Lebanon.[153]

Malaysia

The status of religious freedom in Malaysia is a controversial issue. Islam is the official state religion and the Constitution of Malaysia provides for limited freedom of religion, notably placing control upon proselytization of religions other than Islam to Muslims.[154] Non-Muslims who wish to marry Muslims and have their marriage recognized by the government must convert to Islam.[155] However, questions including whether Malays can convert from Islam and whether Malaysia is an Islamic state or secular state remains unresolved. For the most part the multiple religions within Malaysia interact peacefully and exhibit mutual respect. This is evident by the continued peaceful co-existence of cultures and ethnic groups, although sporadic incidences of violence against Hindu temples,[156] Muslim prayer halls,[157] and Christian churches[158] have occurred as recently as 2010.

Restrictions on religious freedom are also in place for Muslims who belong to denominations of Islam other than Sunni Islam, such as Shia Muslims[159] and Ahmaddiya Muslims.

Illegal words in Penang state

In 2010, a mufti in Penang decreed a fatwa that would forbid non-Muslims to use of 40 words related to Muslim religious practice. Under the Penang Islamic Religious Administration Enactment of 2004, a mufti in Penang state could propose fatwa that would be enforceable by law.[160] The list included words such as "Allah", "Imam", "Sheikh", and "Fatwa", and purported to also make illegal the use of translations of these words into other languages. This decree caused uproar, particularly in the Sikh community, as Sikh religious texts use the term "Allah", with members of the community calling the law unconstitutional.[161] The ban was overturned in 2014, as Penang lawmakers decreed that the Penang Islamic Religious Administration Enactment law only gave the Mufti permission to pass fatwas for the Muslim community, and that these bans were not enforceable on non-Muslim individuals.[162]

Mongolia

The Constitution of Mongolia provides for freedom of religion, and the Mongolian Government generally respects this right in practice; however, the law somewhat limits proselytism, and some religious groups have faced bureaucratic harassment or been denied registration. There have been few reports of societal abuses or discrimination based on religious belief or practice.[163]

Myanmar (Burma)

Every year since 1999 the U.S. State Department has designated Myanmar as a country of particular concern with regard to religious freedom.[164] Muslims, and particularly Muslims of the Rohingya ethnic group, face discrimination at the hands of the Buddhist majority, often with governmental indifference or even active encouragement.

Genocide of Rohingya Muslims

The Rohingya people have been denied Burmese citizenship since the Burmese nationality law (1982 Citizenship Act) was enacted.[165] The Government of Myanmar claims that the Rohingya are illegal immigrants who arrived during the British colonial era, and were originally Bengalis.[166] The Rohingya that are allowed to stay in Myanmar are considered 'resident foreigners' and not citizens. They are not allowed to travel without official permission and were previously required to sign a commitment not to have more than two children, though the law was not strictly enforced. Many Rohingya children cannot have their birth registered, thus rendering them stateless from the moment they are born. In 1995, the Government of Myanmar responded to UNHCR's pressure by issuing basic identification cards, which does not mention the bearer's place of birth, to the Rohingya.[167] Without proper identification and documents, the Rohingya people are officially stateless with no state protection and their movements are severely restricted. As a result, they are forced to live in squatter camps and slums.

Starting in late 2016, the Myanmar military forces and extremist Buddhists began a major crackdown on the Rohingya Muslims in the country's western region of Rakhine State. The crackdown was in response to attacks on border police camps by unidentified insurgents,[168] and has resulted in wide-scale human rights violations at the hands of security forces, including extrajudicial killings, gang rapes, arsons, and other brutalities.[169][170][171] Since 2016, the military and the local Buddhists have killed at least 10,000 Rohingya people,[172] burned down and destroyed 354 Rohingya villages in Rakhine state,[173] and looted many Rohingya houses. The United Nations has described the persecution as "a textbook example of ethnic cleansing". In late September 2017, a seven-member panel of the Permanent Peoples' Tribunal found the Myanmar military and the Myanmar authority guilty of the crime of genocide against the Rohingya and the Kachin minority groups.[174][175] The Myanmar leader and State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi was criticized for her silence over the issue and for supporting the military actions.[176] Subsequently, in November 2017, the governments of Bangladesh and Myanmar signed a deal to facilitate the return of Rohingya refugees to their native Rakhine state within two months, drawing a mixed response from international onlookers.[177][178]

According to the United Nations reports, as of January 2018, nearly 690,000 Rohingya people had fled or had been driven out of Rakhine state who then took shelter in the neighboring Bangladesh as refugees.[179]

Nepal

Nepal has been a secular state since the end of the Nepalese Civil War in 2006, and the Constitution of Nepal adopted in 2015 guarantees religious freedom to all people in Nepal.[180] The Constitution also defines Nepal as a secular state that is neutral toward the religions present in the country.[181] The Constitution also bans actions taken to convert people from one religion to another, as well as acts that disturb the religion of other people.[180]

There have been sporadic incidents of violence against the country's Christian minority. In 2009 and 2015, Christian churches were bombed by anti-government Hindu nationalist groups such as the Nepal Defence Army.[182][183]

Pakistan

Pakistan's penal code includes provisions that forbid blasphemy against any religion recognized by the government of Pakistan.[184] Punishments are more severe for blasphemy against Islam: while acts insulting others' religion can carry a penalty of up to 10 years in prison and a fine, desecration of the Quran can carry a life sentence and insulting or otherwise defiling the name of Muhammad can carry a death sentence.[185] The death sentence for blasphemy has never been implemented, however, 51 people charged under the blasphemy laws have been murdered by vigilantes before their trials could be completed.[186]

The Pakistan government does not formally ban the public practice of the Ahmadi Muslim sect, but its practice is restricted severely by law. A 1974 constitutional amendment declared Ahmadis to be a non-Muslim minority because, according to the Government, they do not accept Muhammad as the last prophet of Islam. However, Ahmadis consider themselves to be Muslims and observe Islamic practices. In 1984, under Ordinance XX the government added Section 298(c) into the Penal Code, prohibiting Ahmadis from calling themselves Muslim or posing as Muslims; from referring to their faith as Islam; from preaching or propagating their faith; from inviting others to accept the Ahmadi faith; and from insulting the religious feelings of Muslims.[187]

Philippines

The 1987 Constitution of the Philippines mandates a separation of church and state,[188][189] significantly limiting the Catholic Church's influence in the country's politics.

The Moro people are a Muslim ethnoreligious minority in the Philippines that have historically fought insurgencies against the government of the Philippines (as well as against previous occupying powers, such as Spain, the United States, and Japan).[190][191][192] They face discrimination from the country's Christian majority.[193]

Republic of China (Taiwan)

Article 13 of the constitution of the Republic of China provides that the people shall have freedom of religious belief.[194]

Saudi Arabia

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is an Islamic theocratic absolute monarchy in which Islam is the official religion.[195] Religious status (defined as "Muslim" or "Non-Muslim") is identified on government-issued identity cards,[196] and non-Muslims face many restrictions, including bans on non-Muslim religious texts and the dismissal of their testimony in court.[195] Officially, the government supports the rights of non-Muslims to practice their faith in private, but non-Muslim organizations claim that there is no clear definition of what constitutes public or private, and that this leaves them at risk for punishment, which can include lashes and deportation. The government of Saudi Arabia does not allow non-Muslim clergy to enter the country for the purpose of conducting services, which further restricts practice.[195]

Members of the Shi’a minority are the subjects of officially sanctioned political and economic discrimination, although the faith is not entirely banned. Shi'a Muslims are barred from employment in the government, military, and oil industries.[195] Ahmadiyya Muslims are officially barred from the country, although many Saudi residents and citizens practice the religion privately.[197]

It is illegal for Muslims to convert or renounce their religion, which is nominally punishable by death.[198] Death sentences have been mandated as recently as 2015,[199] although the most recent execution performed in Saudi Arabia solely for apostasy charges was conducted in 1994.[200] In 2014, the government of Saudi Arabia passed new regulations against terrorism that defined "calling for atheist thought in any form, or calling into question the fundamentals of the Islamic religion on which [Saudi Arabia] is based" as a form of terrorism.[201]

The Saudi Mutaween (Arabic: مطوعين), or Committee for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice (i.e., the religious police) enforces an interpretation of Muslim religious law in public, employing both armed and unarmed officers.[202]

Islamic religious education is mandatory in public schools at all levels. All public school children receive religious instruction that conforms with the official version of Islam. Non-Muslim students in private schools are not required to study Islam. Private religious schools are permitted for non-Muslims or for Muslims adhering to unofficial interpretations of Islam.[195]

Singapore

The constitution provides for freedom of religion; however, other laws and policies restricted this right in some circumstances.[203]

In 1972 the Singapore government de-registered and banned the activities of Jehovah's Witnesses in Singapore on the grounds that its members refuse to perform military service (which is obligatory for all male citizens), salute the flag, or swear oaths of allegiance to the state.[204][205] Singapore has banned all written materials published by the International Bible Students Association and the Watchtower Bible and Tract Society, both publishing arms of the Jehovah's Witnesses. A person who possesses a prohibited publication can be fined up to $1500 (Singapore Dollars $2,000) and jailed up to 12 months for a first conviction.[203]

Sri Lanka

The Constitution of Sri Lanka provides for the freedom of practice of all religions, while reserving a higher status for Buddhism.[206][207] At times, local police and government officials appeared to be acting in concert with Buddhist nationalist organizations. In addition, in NGOs have alleged that government officials provided assistance, or at least tacitly supported the actions of societal groups targeting religious minorities.[208]

Matters related to family law, e.g., divorce, child custody and inheritance are adjudicated under customary law of the applicable ethnic or religious group. For example, the minimum age of marriage for women is 18 years, except in the case of Muslims, who continued to follow their customary religious practices of girls attaining marrying age with the onset of puberty and men when they are financially capable of supporting a family.[209]

During the Sri Lankan Civil War, conflict between Tamil separatists and the government of Sri Lanka at times resulted in violence against temples and other religious targets. However, the primary causes of the conflict were not religious.[210][211]

Syria

The constitution of the Syrian Arab Republic guarantees freedom of religion. Syria has had two constitutions: one passed in 1973, and one in 2012 through a referendum. Opposition groups rejected the referendum; claiming that the vote was rigged.[212] Political instability caused by the Syrian Civil War has deepened religious sectarianism within the country, as well as creating regions in the country where the official government does not have the ability to enforce its laws.[213]

Syria has come under international condemnation over their alleged "anti-Semitic" state media, and for alleged "sectarianism towards Sunni Muslims".[214] This is a claim that Damascus denies. While secular, Syria does mandate that all students go through religious education of the religion that their parents are/were.

The government enforces several measures against what it considers to be Islamic fundamentalism. The Muslim Brotherhood, a political Sunni Muslim organization, is banned in Syria, alongside other Muslim sects that the government considers to be Salafi or Islamist. Those accused of membership in any such organization can be sentenced to long prison terms.[215] In 2016, the Syrian government banned the use of the niqab in universities.[216]

Jehovah's Witnesses in Syria face persecution, as the government banned their religion in 1964 for being a "Zionist organization".[217]

Democratic Federation of Northern Syria

The charter of the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria (also known as Rojava) guarantees the freedom of religion to people living within its territory.[218][219] The government of this region employs various measures to ensure the representation of various ethnic and religious groups in the government, using a system that has been compared to Lebanon's confessionalist system.[220] However, there have been numerous claims made by refugees that YPG units affiliated with the Democratic Federation have forcibly displaced Sunni Arabs from their homes, in addition to destroying businesses and crops.[221] These claims have been denied by Syrian Kurdish authorities.[222]

Free Syrian Army

Battalions affiliated with the Free Syrian Army have been accused of taking hostages and murdering members of religious minorities in territory held by their soldiers.[223][224]

Jihadist groups

Jihadist groups, such as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant and Jabhat Al-Nusra have enforced very strict interpretations of Sunni religious law in their territory, executing civilians for blasphemy, adultery, and other charges.[225] Watchdog organizations have documented extensive persecution of Yazidi people, particularly women, who have been routinely forced into sexual slavery by the Islamic State in what Human Rights Watch described as an "organized system of rape and sexual assault".[226]

Tajikistan

Freedom of religion in Tajikistan is provided for in Tajikistan's constitution. The Tajikistan government, enforces a policy of active secularism.[227]

Tajikistan is unique for barring minors from attending public religious ceremonies, with the exception of funerals (where they must be accompanied by an adult guardian).[228] Minors are allowed to practice religion in private.[227] Hanafi mosques bar women from attending services, a policy decreed by a religious council with support from the government.[227]

Tajikistan's policies reflect a concern about Islamic extremism, a concern shared by much of the general population. The government actively monitors the activities of religious institutions to keep them from becoming overtly political. A Tajikistan Ministry of Education policy prohibited girls from wearing the hijab at public schools.[227]

Turkey

The Constitution of Turkey establishes the country as a secular state and provides for freedom of belief and worship and the private dissemination of religious ideas. However, other constitutional provisions for the integrity of the secular state restrict these rights. The constitution prohibits discrimination on religious grounds.[229] Article 219 of the penal code prohibits imams, priests, rabbis and other religious leaders from "reproaching or vilifying" the government or the laws of the state while performing their duties, punishable by several months in prison.[230]

Religious affiliation is listed on national identity cards, despite Article 24 of the 1982 constitution which forbids the compulsory disclosure of religious affiliation. Members of some religious groups, such as the Bahá'í, are unable to state their religious affiliation on their cards because it is not included among the option, and thus must report their religion as "unknown" or "other".[230]

Treatment of Muslims

The Turkish government oversees Muslim religious facilities and education through its Directorate of Religious Affairs, under the authority of the Prime Minister. The directorate regulates the operation of the country's 77,777 registered mosques and employs local and provincial imams (who are civil servants). Sunni imams are appointed and paid by the state.[231] Historically, Turkey's Alevi Muslim minority has been discriminated against within the country. However, since the 2000s, various measures granting Alevis more equal recognition as a religious group have been passed at the local and national levels of government.[232][233][231] Other Muslim minorities, such as Shia Muslims, largely do not face government interference in their religious practice, but also receive no support from the state.[234]

Since the 2000s Turkish Armed Forces have dismissed several members for alleged Islamic fundamentalism.[235][236][237]

Treatment of other religious groups

In the 1970s, the Turkish High Court of Appeals issued a ruling allowing for the expropriation of properties acquired after 1936 from religious minorities.[238] Later rulings in the 2000s have restored some of this property, and generally allow minorities to acquire new properties.[239] However, the government has continued to apply an article allowing it to expropriate properties in areas where the local non-Muslim population drops significantly or where the foundation is deemed to no longer perform the function for which it was created. There is no specific minimum threshold for such a population drop, which is left to the discretion of the GDF. This is problematic for small populations (such as the Greek Orthodox community), since they maintain more properties than the local community needs; many are historic or significant to the Orthodox world.[240]

Greek Orthodox, Armenian Orthodox and Jewish religious groups may operate schools under the supervision of the Education Ministry. The curricula of the schools include information unique to the cultures of the groups. The Ministry reportedly verifies if the child's father or mother is from that minority community before the child may enroll. Other non-Muslim minorities do not have schools of their own.[241]

Churches operating in Turkey generally face administrative challenges to employ foreign church personnel, apart from the Catholic Church and congregations linked to the diplomatic community. These administrative challenges, restrictions on training religious leaders and difficulty obtaining visas have led to a decrease in the Christian communities.[242] Jehovah's Witnesses have faced imprisonment and harassment, largely connected to their religiously grounded conscientious objection to obligatory military service.[243]

Turkmenistan

The Constitution of Turkmenistan provides for freedom of religion and does not establish a state religion. However, the Government imposes legal restrictions on all forms of religious expression. All religious groups must register in order to gain legal status; unregistered religious activity is illegal and may be punished by administrative fines. While the 2003 law on religion and subsequent 2004 amendments had effectively restricted registration to only the two largest groups, Sunni Muslim and Russian Orthodox, and criminalized unregistered religious activity, presidential decrees issued in 2004 dramatically reduced the numerical thresholds for registration and abolished criminal penalties for unregistered religious activity; civil penalties remain. As a result, nine minority religious groups were able to register, and the Turkmenistan government has permitted some other groups to meet quietly with reduced scrutiny.[244]

Ethnic Turkmen identity is linked to Islam. Ethnic Turkmen who choose to convert to other religious groups, especially the lesser-known Protestant groups, are viewed with suspicion and sometimes ostracized, but Turkmenistan society historically has been tolerant and inclusive of different religious beliefs.[244]

Uzbekistan

The Constitution of Uzbekistan provides for freedom of religion and for the principle of separation of church and state.[245] However, the government restricts these rights in practice. The government permits the operation of what it considers mainstream religious groups, including approved Muslim groups, Jewish groups, the Russian Orthodox Church, and various other Christian denominations, such as Roman Catholics, Lutherans, and Baptists. Uzbek society generally tolerates Christian churches as long as they do not attempt to win converts among ethnic Uzbeks. The law prohibits or severely restricts activities such as proselytizing, importing and disseminating religious literature, and offering private religious instruction.[246]

A number of minority religious groups, including congregations of some Christian denominations, operate without registration because they have not satisfied the strict requirements set by the law. As in previous periods, Protestant groups with ethnic Uzbek members reported operating in a climate of harassment and fear. The government has been known to arrest and sentence Protestant pastors, and to otherwise raid and harass some unregistered groups, detaining and fining their leaders and members.

The government works against unauthorized Islamic groups suspected of extremist sentiments or activities, arresting numerous alleged members of these groups and sentencing them to lengthy jail terms. Many of these were suspected members of Hizb ut-Tahrir, a banned extremist Islamic political movement, the banned Islamic group Akromiya (Akromiylar), or unspecified Wahhabi groups. The government generally does not interfere with worshippers attending sanctioned mosques and granted approvals for new Islamic print, audio, and video materials. A small number of "underground" mosques operated under the close scrutiny of religious authorities and the security service.[246]

Religious groups enjoyed generally tolerant relations; however, neighbors, family, and employers often continued to pressure ethnic Uzbek Christians, especially recent converts and residents of smaller communities. There were several reports of sermons against missionaries and persons who converted from Islam.[246]

Vietnam

The Constitution formally allows religious freedom.[247] Every citizen is declared to be allowed to freely follow no, one, or more religions, practice his or her religion without violating the law, be treated equally regardless of his or her religion, be protected from being violated his or her religious freedom, but is prohibited to use religion to violate the law.[247]

All religious groups and most clergy must join a party controlled supervisory body, religions must obtain permission to build or repair houses of worship, run schools, engage in charity or ordain or transfer clergy, and some clergy remain in prison or under serious state repression.[248]

Europe

Austria

Austria guarantees freedom of religion through various constitutional provisions and through membership in various international agreements. In Austria, these instruments are deemed to allow any religious group to worship freely in public and in private, to proselytize, and to prohibit discrimination against individuals because of their religious allegiances or beliefs. However, part of the Austrian constitutional framework is a system of cooperation between the government and recognized religious communities. The latter are granted preferential status by being entitled to benefits such as a tax-exempt status and public funding of religious education.[249]