Fortaleza

| Fortaleza | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality | |||

| Municipality of Fortaleza | |||

Clockwise from top: Panorama view of downtown Aratanha and Maranguape area, Theatro José de Alencar, Fortaleza Metropolitan Cathedral, A monument of the Guardian of Iracema in Iracema Beach, Meireles Beach, Ingleses Bridge in Iracema Beach, Dragão do Mar Center of Art and Culture | |||

| |||

|

Nickname(s): Fortal Miami Brasileira (Brazilian Miami) Terra da Luz (Land of Light) | |||

| Motto(s): "Fortitudine" (Latin) | |||

| |||

Fortaleza Location in Brazil | |||

| Coordinates: 3°43′6″S 38°32′34″W / 3.71833°S 38.54278°WCoordinates: 3°43′6″S 38°32′34″W / 3.71833°S 38.54278°W | |||

| Country |

| ||

| State |

| ||

| Founded | April 13, 1726 | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | Mayor-council | ||

| • Mayor | Roberto Cláudio (PDT) | ||

| • Vice Mayor | Moroni Torgan (DEM) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Municipality | 314.93 km2 (121.60 sq mi) | ||

| • Metro | 7.440,053 km2 (2.872621 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 21 m (69 ft) | ||

| Population (2016) | |||

| • Municipality | 2,609,716 | ||

| • Rank | 5th | ||

| • Metro | 4,019,213 | ||

| • Metro density | 540.21/km2 (1,399.1/sq mi) | ||

| Demonym(s) | Portuguese: Fortalezense | ||

| Time zone | UTC-3 (BST) | ||

| Postal Code | 60000-000 | ||

| Area code(s) | +55 85 | ||

| Website | Fortaleza, Ceará | ||

Fortaleza ([foʁtaˈlezɐ], locally [fɔɦtaˈlezɐ], Portuguese for Fortress) is the state capital of Ceará, located in Northeastern Brazil. It belongs to the Metropolitan mesoregion of Fortaleza and microregion of Fortaleza. Located 2285 km (1420 miles) from Brasilia, the federal capital, the city has developed on the banks of the creek Pajeú, and its name is an allusion to Fort Schoonenborch, which gave rise to the city, built by the Dutch during their second stay in the area between 1649 and 1654. The motto of Fortaleza, present in its coat of arms is the Latin word Fortitudine, which means "with strength/courage".

In 2013, Fortaleza was the twelfth richest city in the country in GDP and second in the Northeast, with 49 billion reais (US$21 billion). It also has the third richest metropolitan area in the North and Northeast regions. It is an important industrial and commercial center of Brazil, the eighth nation's largest municipal purchasing power. According to the Ministry of Tourism, the city reached the marks of second most desired destination of Brazil and fourth Brazilian city that receives more tourists. The BR-116, the most important highway of the country, starts in Fortaleza. The municipality is part of the Common Market of Mercosur Cities, and also the Brazilian capital which is closest to Europe, 5608 km (3484 miles) from Lisbon, Portugal.[1][2]

To the north of the city lies the Atlantic Ocean; to the south are the municipalities of Pacatuba, Eusébio, Maracanaú and Itaitinga; to the east is the municipality of Aquiraz and the Atlantic Ocean; and to the west is the municipality of Caucaia. Residents of the city are known as Fortalezenses. Fortaleza is one of the three leading cities in the Northeast region together with Recife and Salvador.[2][3]

The city was one of the host cities of the 2014 FIFA World Cup.

History

Colonial period

Fortaleza's history began on February 2, 1500, when Spaniard Vicente Pinzón landed in Mucuripe's cove and named the new land Santa Maria de la Consolación. Because of the Treaty of Tordesillas, the discovery was never officially sanctioned. Colonisation began in 1603, when the Portuguese Pero Coelho de Souza constructed the Fort of São Tiago and founded the settlement of Nova Lisboa (New Lisbon).[4] After a victory over the French in 1612, Martins Soares Moreno expanded the Fort of São Tiago and changed its name to Forte de São Sebastião.[5]

In 1630 the Dutch invaded the Brazilian Northeast and in 1637 they took the Fort of São Sebastião and ruled over Ceará. In battles with the Portuguese and natives in 1644 the fort was destroyed.[5] Under captain Matthias Beck the Dutch West Indies Company built a new fortress by the banks of river Pajeú. Fort Schoonenborch ("graceful stronghold") officially opened on August 19, 1649. After the capitulation of Pernambuco in 1654, the Dutch handed over this fortress to the Portuguese, who renamed it Fortaleza da Nossa Senhora de Assunção ("Fort of Our Lady of the Assumption"), after which the city of Fortaleza takes its name.[6]

Fortaleza was officially founded as a village 1726, becoming the capital of Ceará state in 1799.[7]

Imperial period

During the 19th century, Fortaleza was consolidated as an urban centre in Ceará, supported by the cotton industry. With the transformation of the city into a regional export center and with the increase of direct navigation to Europe, the Customs of Fortaleza was built in 1812. Silva Paulet played an important role in the structural evolution of the city, erecting works like the Fortress of Our Lady of the Assumption in 1812, in the place of what remained of the Fort of Our Lady of the Assumption, and the Public Walk in 1820, besides having been The author of the first urban plan of the city, from 1812. In 1824, the city was targeted by the revolutionaries of Confederation of the Equator. Especially in the second half of the century, as a result of the fertile cotton era, the city was seized by a great period of urban development and construction of remarkable equipment, such as the Lyceum of Ceará and the Lighthouse of Mucuripe in 1845, Santa Casa de Misericórdia In 1861, the Prainha Seminary in 1864, the water supply system in 1866, the Public Library in 1867, the Public Chain in 1870, the Ceará Railroad Network, the Fortaleza Port on the Metallic Bridge, textile factories, intellectual centers and Communication vehicles, for example. The period was marked as the belle époque of Fortaleza, representing a time of economic consecration that was reflected in areas such as architecture, culture and intellectual production. Between the years 1846 and 1877, the city went through a period of enrichment, economic and infrastructural improvement.[8]

In order to discipline the growth of the city, Adolpho Herbster continued the urban planning scheme conceived by Silva Paulet in 1818, characterized by the tracing of chess roads, and, inspired by the reforms carried out in Paris by Baron Haussman, designed the Topographic Plan of the Fortress and Suburbs, in 1875, definitive landmark of municipal urbanism. In the 1870s and 1880s, the Ceará Abolitionist Movement and the republican ideals that culminated in the liberation of the slaves in Ceará on March 25, 1884, four years before the Golden Law came into being and were strengthened. The main event of the abolitionist cause of Ceará in the capital was the popular uprising, between January 27 and 31, 1881, led by the Dragon-headed raiders, who ended the slave trade in the capital, fueling the state libertarian impetus and National level. The intellectuals of the literary movement of the Spiritual Bakery, which emerged in 1892, greatly contributed to the diffusion of progressive ideas in Fortaleza.

Republican period

In the twentieth century, Fortaleza underwent significant urban changes, with improvements and the rural exodus to the city, with growth mostly towards the end of the decade of 1910, this made the city the seventh most populated city in Brazil. In 1922, Fortaleza reached its first hundred thousand inhabitants with the annexation of the cities of Messejana and Parangaba, now important districts of the city.[9] In 1954, the first university in the city was created, the Universidade Federal do Ceará(UFC) .[10]

In 1983 DIF I started to integrate the territory of the new city of Maracanaú, which, just some years ago, was made again part of the Greater Fortaleza (the city's Metropolitan area). In the 1980s, Fortaleza exceeded Recife in population terms, becoming the second most populous city in Northeastern Brazil, with 2,571,896 inhabitants.[11]

During the political awakening that followed the military regime, the people elected the city's first woman mayor, Maria Luíza Fontenele of the Brazilian Workers' Party, which meant that the city administration was controlled by a party of the centre-left. At the end of the twentieth century, the administration of the city hall and the city underwent a range of structural changes with the opening of several avenues, hospitals, cultural spaces and it became one of the main tourist destinations in the Northeast and in Brazil.[12]

Geography

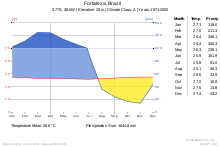

Climate

Fortaleza has a typical tropical climate, specifically a tropical wet and dry climate, with high temperatures and relative humidity throughout the year. However, these conditions are usually relieved by pleasant winds blowing from the ocean. Average temperatures are not much different throughout the year. December is the warmest month, with a high of 30.7 °C (87.3 °F)[13] and low of 24.6 °C (76.3 °F).[14] The rainy season spans from January to June, with rainfall particularly prodigious in March and April.[15] The average annual temperature is 26.6 °C (79.9 °F).[16] The relative humidity in Fortaleza is 79%,[17] with average annual rainfall of 1,608.4 millimetres (63.32 in).[15] There is usually rain during the first seven months of the year from January to July. During this period, relative humidity is high. Fortaleza's climate is usually very dry from August to December, with very little rainfall.[15][17]

Rainfall is like all of Northeastern Brazil among the most variable in the world, comparable (for similar average annual rainfalls) to central Queensland cities like Townsville and Mackay.[18] In the notorious drought year of 1877 as little as 468 millimetres or 18.43 inches fell, and in 1958 only 518 millimetres or 20.39 inches, but in the Nordeste’s record wet year of 1985 Fortaleza received 2,841 millimetres or 111.85 inches.

| Climate data for Fortaleza (1961–1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 37.7 (99.9) |

33.3 (91.9) |

32.8 (91) |

32.6 (90.7) |

32.8 (91) |

31.8 (89.2) |

33 (91) |

34.4 (93.9) |

32.7 (90.9) |

33.4 (92.1) |

33 (91) |

33.2 (91.8) |

37.7 (99.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.5 (86.9) |

30.1 (86.2) |

29.7 (85.5) |

29.7 (85.5) |

29.9 (85.8) |

29.6 (85.3) |

29.5 (85.1) |

29.9 (85.8) |

30.2 (86.4) |

30.5 (86.9) |

30.7 (87.3) |

30.7 (87.3) |

30.1 (86.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 27.1 (80.8) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.2 (79.2) |

26.2 (79.2) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.6 (78.1) |

26 (79) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.9 (80.4) |

27.2 (81) |

27.3 (81.1) |

26.6 (79.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 24.4 (75.9) |

24 (75) |

23.6 (74.5) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.3 (73.9) |

22.8 (73) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.7 (72.9) |

23.4 (74.1) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.4 (75.9) |

24.6 (76.3) |

23.6 (74.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 20 (68) |

21.2 (70.2) |

20.2 (68.4) |

20 (68) |

20.6 (69.1) |

20.3 (68.5) |

19.4 (66.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

20.5 (68.9) |

21 (70) |

21.3 (70.3) |

21 (70) |

19.4 (66.9) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 119.1 (4.689) |

204.6 (8.055) |

323.1 (12.72) |

356.1 (14.02) |

255.6 (10.063) |

141.8 (5.583) |

94.7 (3.728) |

21.8 (0.858) |

22.7 (0.894) |

13 (0.51) |

11.8 (0.465) |

44.1 (1.736) |

1,608.4 (63.321) |

| Average rainy days (≥ ≥ 1 mm) | 11 | 15 | 22 | 21 | 19 | 14 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 132 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 78.1 | 81.4 | 84.7 | 85.2 | 83.6 | 81 | 78.8 | 75.3 | 74.4 | 74 | 73.7 | 75.9 | 78.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 225.2 | 182.3 | 150 | 157.1 | 208.4 | 238.7 | 268.3 | 295.9 | 281.6 | 291.4 | 282.2 | 262.3 | 2,843.4 |

| Source: Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology (INMET).[13][14][15][16][17][19][20][21][22] | |||||||||||||

Vegetation

In Fortaleza there are some remaining areas of mangrove in preserved areas.[23][24] The municipality contains the 3,320 hectares (8,200 acres) Pedra da Risca do Meio Marine State Park created in 1997 to support an offshore area of reefs of ecological and tourist importance.[25]

Ecology and environment

The vegetation of Fortaleza is typically coastal. The restinga areas are found in dune regions near the mouths of the Ceará, Cocó and Pacoti rivers, in the beds of which there is still a mangrove forest. In other green areas of the city, there is no longer native vegetation, constituting of varied vegetation, fruit trees more commonly.[26] The city is home to seven environmental conservation units. These are the Sabiaguaba Dunes Municipal Natural Park, the Sabiaguaba Environmental Protection Area, the Maraponga Lagoon Ecological Park, the Cocó Ecological Park, the Ceará River Estuary Environmental Protection Area, the Environmental Protection Area of the Rio Pacoti and the Pedra da Risca do Meio Marine State Park.[27] There is also, in the city, the Area of Relevant Ecological Interest of Sírio Curió, that protects the last enclave of Atlantic Forest in the urban zone.[28]

The Cocó River is part of the river basin of the east coast of Ceará and has a total length of about 50 km in its main area. The park is inserted in the area of greater environmental sensitivity of the city, where it is possible to identify geoenvironmental formations such as coastal plain, fluvial plain and surface of the coastal trays. The Cocó river mangrove is home to mollusks, crustaceans, fish, reptiles, birds and mammals. The park has a structure of visitation, with guides, ecological trails and equipment and events of environmental education and ecotourism. The Coaçu River, affluent of the river Cocó, forms in its bed the lagoon of the Precabura.[29][30]

The Rio Pacoti provides much of the water supply for Fortaleza.[31] At the municipal boundary with Caucaia, the estuary of the Rio Ceará is covered by an environmental protection area (APA), which was set up in 1999.[32]

Demographics

.jpg)

According to the 2010 IBGE Census, there were 2,315,116 people residing in the city of Fortaleza.[33] The census revealed the following numbers: 1,403,292 Pardo (multiracial) people (57.2%), 901,816 White people (36.8%), 110,811 Black people (4.5%), 33,161 Asian people (1.4%), 3,071 Amerindian people (0.1%).[34]

In 2010, the city of Fortaleza was the 5th most populous city proper in Brazil, after São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Salvador, and Brasília.[35]

In 2010, the city had 433,942 opposite-sex couples and 1,559 same-sex couples. The population of Fortaleza was 53.2% female and 46.8% male.[34]

The following cities are included in the metropolitan area of Fortaleza (ordered by population): Fortaleza, Caucaia, Maracanaú, Maranguape, Aquiraz, Pacatuba, Pacajus, Horizonte, São Gonçalo do Amarante, Itatinga, Guaiúba and Chorozinho.[36]

According to a genetic study from 2011, 'pardos' and whites' from Fortaleza, which comprise the largest share of the population, showed up a degree of European ancestry of about 70%, being the rest basically divided between Native American and African ancestries.[37] A 2015 study, however, found out the following composition in Fortaleza: 48,9% of European contribution, 35,4% of Native American input and 15,7% of African ancestry.[38]

.png)

Religion

.png)

The prevailing religion of Fortaleza is the Roman Catholic branch of Christianity, due to the influence of Portuguese settlers and missionaries during the colonial rule of Brazil.

| Religious affiliation | Percentage | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Catholic | 79.0% | 1,691,487 |

| Protestant | 12.58% | 269,469 |

| No religion | 5.99% | 128,190 |

| Kardecist | 0.83% | 17,780 |

| Jehovah's Witnesses | 0.64% | 13,758 |

| Other religions | 0.7% | 15,923 |

According to the census of 2010, 1,664,521 people, 67.88% of the population, followed Roman Catholicism, 523,456 (21.35%) were Protestant, 31 691 (1.29%) represented Spiritism and 162 985 (6.65%) had no religion whatsoever. Other religions, such as Umbanda, Candomblé, other Afro-Brazilian religions, Spiritualism, Judaism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, other Eastern religions, Esotericism and other Christian churches like Mormon had a smaller number of adherents.[40]

Politics

The administration of the municipality is made from the executive and legislative branches.[41] Roberto Cláudio, of the PDT, won 650,607 votes in the 2012 election, and was elected mayor.[42][43] Legislative power rests with the City Council of Fortaleza, composed of 43 city councilors, elected for four-year terms, responsible for drafting municipal laws and supervising the executive.[44] The municipality is, in addition, governed by organic law. In January 2015, there were 1 659 091 voters in Fortaleza (26,457% of the total state),[45] distributed in thirteen electoral zones. The number of persons directly and indirectly employed in the municipal public administration in 2013 was respectively 31 318 and 4 950.[46]

The city also houses the seat of state executive power, the Abolition Palace, occupied by governor Camilo Santana, of the PT, elected in the general elections in Brazil in 2014.[47] historically headquarters of the Iracema Club, which was Ceded to the Municipal Hall and now houses municipal executive bodies.[48] In the city, there is the Administrative Center Governor Virgílio Távora.[49]

Fortaleza is also the regional headquarters of several federal government institutions. Among the military institutions present in the city, are located in the Fortaleza Air Base, an important military aviation milestone during World War II, a Port Authority of Ceará, a School of Apprentice Sailors of Ceará and the Command of the Tenth Military Region. The city also has units of the International Committee of the Red Cross and UNICEF.[50] Since 1996, a city is part of the Common Market of Cities of Mercosur.[51]

Economy

At the beginning of the decade of 2000, among the capitals of the Northeast, Fortaleza had the third largest Gross Domestic Product (GDP), being surpassed by Recife and Salvador.[52] In 2012, the GDP of Fortaleza reached the value of 43.4 billion Reais, the tenth highest of the country.[53] In the same year, the value of taxes on products net of subsidies at current prices was R $6,612,822,000 and the municipality's GDP per capita was R$17.359,53.[54] The city's booming economy is reflected in purchasing power, the country's eighth largest, with estimated consumption potential at 42 billion reais in 2014.[55]

The main economic source of the municipality is centered in the tertiary sector, with its diversified segments of commerce and service rendering. Next, the secondary sector stands out, with the industrial complexes.[54] In 2012, the percentage contribution of each sector to the municipal economy was 0.07%, 15.8% and 68.8% of the primary, secondary and tertiary sectors, respectively. The wealth of the capital is largely due to activities coming from all over the metropolitan region, whose economy is the third strongest in the North and Northeast regions and whose population is almost four million. In 2012, the city had 69,605 units and 64,674 companies and active commercial establishments, in addition to 873,746 employees and 786,521 salaried employees. Wages, together with other types of remuneration, amounted to 17,103,562 reais and the average income of the municipality was 2.7 minimum wages.[56]

Culture

.png)

According to the Master Plan of Fortaleza, the Special Areas for the Preservation of Historic, Cultural and Archaeological Heritage are the regions of the Center, Parangaba, Alagadiço Novo/José de Alencar, Benfica, Porangabuçu and Praia de Iracema. Properties of conservation interest.[57] The architectural heritage of Fortaleza in the form of fallen goods, however, is predominantly concentrated in the center of the city.[58][59] The Mucuripe Lighthouse is unfortunately in ruins today, Ceará and Fortaleza were part of the pioneering group of states and cities to adopt public policies to protect the living intangible heritage of their culture, through the Masters of Culture program.[60]

Museums, theatres and cultural spaces

The cultural life of Fortaleza is diverse and fruitful. Many artists, writers, painters and singers use the city's busiest stages and squares to stimulate regional culture. Among the theaters, the largest and most popular are Theatro José de Alencar, the stage of the main local and universal culture shows, the São José Theater, the São Luiz Cinema Theater, Teatro RioMarand Teatro Via Sul.[61] The Ceará Museum houses numerous artifacts from the memory of Fortaleza, among pieces of paleontology, archeology and indigenous anthropology, furniture, items of struggles and popular revolts, of religiosity and about the intellectual production and irreverence of Ceará.[62] The Dragão do Mar Center of Art and Culture is the main cultural space of Fortaleza. In this center are the Ceará Museum of Culture, the Museum of Contemporary Art of Ceará, theaters, a planetarium, cinemas, shops and spaces for public presentations, as well as housing the Public Library Governador Menezes Pimentel, Oporto Iracema of the Arts and the School of Arts and Crafts Thomaz Pompeu Sobrinho.[63] The Casa de Jose Alencar is one of the Brazilian museums recognised as dealing with Brazilian literature.[64] It was opened in 1964 and houses art collections, a gallery, a library and the ruins of the first steam power plant in Ceará.[65] In the different SERs of the city, the complexes of the CUCA Network are spread, which are great facilities dedicated to art, leisure and education, especially for young people.[66]

Freemasonry is represented by the Grand Masonic Lodge of Ceará and the Great State East of Ceará. There are also service clubs in the city, such as the Lions Club and Rotary International.[67]

The Ceará handicraft has its main market and showcase in Fortaleza. In the city, there are several specific places for trade in handicraft products, such as the Ceará Craft Center (CeArt), Ceará Tourism Center (Emcetur), Crafts Fair of Beira-Mar, and on Avenida Monsenhor Tabosa.[68]

Literature and cinema

.png)

The main literary manifestation of Fortaleza's history emerged at the end of the 19th century, in the cafes of Praça do Ferreira, known as the Spiritual Bakery, a pioneer in the dissemination of modern ideas in Brazilian literature that would only be adopted nationally in the following century, in the Modern Art Week.[69][70] The most important historical entities of high culture still present in the city are the Ceará Institute and the Ceará Academy of Letters, the first academy of letters created in Brazil, founded in 1887 and 1894 respectively. The Ceará Institute has helped launch important names in national historiography and philosophy, such as Farias Brito and Capistrano de Abreu.[71] Among the writers who are members of the Cearense Academy of Letters and members or patrons of the Brazilian Academy of Letters, are Gustavo Barroso, Araripe Júnior, José de Alencar, Heráclito Graça, Franklin Tavora, Clóvis Beviláqua and Rachel de Queiroz, the first woman to Be part of the entity. The Casa de Juvenal Galeno is another historical cultural institution of Fortaleza, named after one of the greatest poets born in the city, Juvenal Galeno. The house became well known for its festivals of poetry and seminaries.[72]

In cinema, the most well known name is Zelito Viana, director of films like Villa-Lobos: A Life of Passion and Life and Death of Severina. More recently, Karim Aïnouz has directedMadame Satã, Suely in the Sky and Futuro Beach, and script of Lower City, Cinema, Aspirins and Vultures and Behind the Sun. Another current exponent of cinema born in Fortaleza is Halder Gomes, director and screenwriter of Holliúdy Cinema. New filmmakers in the city have gained in recent years prominent exhibitions such as at the Rio de Janeiro International Film Festival.[73] The most traditional cinema event in Fortaleza is the Cine Ceará (Ibero-American Film Festival), considered one of the main festivals of the country.[74]

Fashion

The main fashion name in the city is the Lino Villaventura, who, from Fortaleza, designed himself nationally and internationally and today is one of the main names of São Paulo Fashion Week, besides being one of the founding designers of this fashion week.[75] There are major events in the city, such as the Dragão Fashion Brasil, considered the largest fashion event in the Northeast and the third largest in the country.[76]

Much of the clothing that is produced in Ceará flows through Fortaleza, which in turn is recognized as one of the most important textile centers of the country, giving the garment industry great weight in the metropolitan economy.[77] Brands of the city like Santana Textiles and headquarters of brands like Esplanada and Otoch have considerable regional influence.[78]

Music

Forró is the most popular musical genre in the city. Bands originating in Fortaleza, such as Mastruz with Leite and Aviões do Forró, were responsible for the popularization of electronic forró, which promoted the revaluation of the accordion in the genre and brought it closer to pop music. The forró pé-de serra, however, still holds great cultural influence and commercial prominence in the city.[79]

In Música popular brasileira, some of the names from Fortaleza were Fagner, Ednardo, Belchior (from Sobral but was lived in Fortaleza) and Amelinha.[79] The musical tradition of Fortaleza, however, goes back to the composer Alberto Nepomuceno, one of the greatest names in classical music in Brazil, a pioneer in the development of the country's musical nationalism, and therefore considered the "founder of Brazilian music". The Alberto Nepomuceno Conservatory is one of the city's leading music schools.[79]

Carnival

Fortaleza Carnival season is not as famous as that in other northeastern cities like Salvador or Recife, as the local population prefer to spend the holiday at others beach cities of Ceará. Through the streets of Fortaleza, the Carnival brings the samba together with festivities as a celebration of Fortaleza's past and diverse culture. It is particularly notable for its unique style of maracatu known as maracatu cearense.[80]

Cuisine

The gastronomy of Fortaleza is very close to the typical Northeastern cuisine, and, traditional include the baião de dois, usually accompanied by barbecue of mutton or meat of sun, and "tapioca" which is a pancake made from the starch of cassava. The seafood is another ingredient of typical dishes of fortalezeense cuisine, such as the steak moqueca and the mackerel and snapper fish.[81][82]

The fruit of the sea identity of the coast of the state is the crab. Shrimp and lobster are also widely used delicacies in dishes such as shrimp rice or shrimp dumplings.[83]

Tourism

Acquario Ceará, the third largest aquarium in the world, is under construction on the edge of the city.[84] Attractions such as the Beach Park theme park, located in the Great Fortaleza, Avenida Beira Mar and its bars, restaurants and music clubs, the beaches of Futuro and Iracema and Pirata Bar have placed Fortaleza among the Brazilian destinations preferred by Europeans.[85]

Scuba diving is possible in the area of Pedra da Risca do Meio Marine State Park, a marine protected area located about 10 nautical miles from the shoreline of Fortaleza.[86]

Historic Centre of Fortaleza

Historic Centre of Fortaleza.jpg) Aerial view of the city

Aerial view of the city Boats and skyscrapers in the litoral. Most five-stars and four-star hotels.

Boats and skyscrapers in the litoral. Most five-stars and four-star hotels. Beach Park, the largest water park in Latin America.

Beach Park, the largest water park in Latin America.

Urban beaches

Fortaleza has about 25 kilometres (16 mi) of urban beaches. From North to South, the urban beaches of Fortaleza are Iracema, Meireles, Mucuripe and Praia do Futuro. Each beach has its own peculiarities:

- Iracema is the Bohemian beach, with bars and nightclubs;[87]

- Mucuripe is the place where jangadas can be found. Still used by fishermen to go into high seas, jangadas can be seen along the way during the afternoon and evenings, and returning from the sea in the morning; part of the catch of the day is sold in an old style fish market.[88]

.jpg)

Mucuripe Beach

Mucuripe Beach Futuro Beach

Futuro Beach Meirelles Beach

Meirelles Beach

Education

In 2010, the level of the education factor of the Strengthening Human Development Index was medium, despite its great advance, which went from 0.367 to 0.695 between 1991 and 2010. According to data from the 2010 Human Development Atlas of Brazil, Fortaleza's adult education levels were divided as follows: 8.57% did not complete primary school or were illiterate, 62.43% had completed elementary education, 45.93% had completed high school and 13.73% had completed higher education; All indices above the Brazilian average. The average strength was 10.04 years expected from the study, more than the estimate from Ceará, 9.82. According to the same study, 4.14% of children aged 5 and 6 were not in school.

Health

The health indexes of the Fortaleza population are better than the Brazilian average. According to data from 2010, the infant mortality rate up to one year old was 15.8% in Fortaleza, against a Brazilian average of 16.7%.[89] By 2013, 90.6% of children under one year of age had their immunization records up to date. In 2012, 37,577 live births were registered, and the infant mortality rate up to five years of age was 13.2%. Of the total number of children under two years old weighed by the Family Health Program in 2013, 0.8% were malnourished.[90]

In 2009, Fortaleza had a total of 35 general hospitals, of which 11 were public, 21 were private, two were philanthropic, and one was a trade union. The Doctor José Frota Institute is the largest hospital administered by the Municipal Government, and the General Hospital of Fortaleza is the largest hospital administered by the State Government. In addition, it had 54 specialized hospitals and eight polyclinics. The total number of physicians working in the health network of the municipality was 13,604, approximately 5.4 per thousand inhabitants.[91] Fortaleza has 117 units of health posts, three UPAs administered by the municipality and six administered by the state.[92][93] The first hospital built in Fortaleza was the Santa Casa de Misericórdia, founded in 1861.[94] Among the most important public health institutions in the city, the most important is the Dr. José Frota Institute, the largest hospital administered by the Municipal Government, and the General Hospital of Fortaleza, the largest hospital administered by the State Government. Among the private institutions, the largest are the Unimed Fortaleza Regional Hospital, Antônio Prudente Hospital, Monte Klinikum Hospital and São Mateus Hospital.[95] There are also, in Fortaleza, three units of the Popular Pharmacy of Brazil.[96]

One of the most important basic health programs in Fortaleza is the Family Health Program, within which the city is in third place in the country in extension of coverage, with hundreds of teams distributed in dozens of care units.[97] The Emergency Mobile Care Service (SAMU) is the municipality's health care service, which serves an average of 200 daily occurrences.[98]

Fortaleza is endowed with several medical courses, but the best and most traditional of them is that of the Faculty of Medicine of the Federal University of Ceará, created in 1948, which manages a large structure of specialized health institutions between hospitals and clinics, Among them the University Hospital Walter Cantídio, leader in Latin America in liver transplantation.[99] The Faculty of Medicine of the UFC is the 13th best medical school in Brazil, 2nd best medical school in the North and Northeast regions and the best medical school in Ceará. UFC's medical degree is still one of the most popular in the country.[100]

Transport

International Airport

The Pinto Martins – Fortaleza International Airport, located in the center of Fortaleza, was built between 1996 and 1998, when it came to be classified as International.[101] The airport is now undergoing an expansion process, from which the number of boarding bridges will increase from seven to sixteen and the passenger terminal will be expanded from 38,000 m² to 133,000 m². In 2014, the airport was capable of serving 6.2 million passengers per year, but after expansion, capacity would be 11.2 million.[102]

Pinto Martins Airport is the third busiest airport in the Northeast Region and one of the busiest in the country, receiving on average 1,500 international aircraft and 65,000 domestic aircraft per year. In 2013, it received more than 5.9 million passengers.[103]

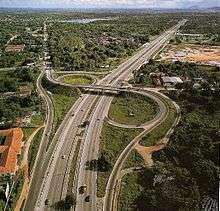

Roads

In 2013, Fortaleza had 908,074 vehicles, of which 511,109 were cars, and 229 154 motorcycles.[105] Traffic density at peak times in the city is rated as the fourth largest in the country, with 48% of congested roads.[105] The cycle network of Fortaleza is composed of 116.4 km, of which 78.8 km are cycle paths and 37.6 km are cycle paths. The municipality also has a public bicycle system, Bicicletar, which had 40 stations and 400 units in April 2015. In 2015, the municipal taxi fleet was composed of 4 886 vehicles, including common, adapted and special use vehicles.[105]

The land access to the municipality is made by highways BR-116, BR-020, BR-22], CE-090, CE-085, CE-065, CE-060, CE-040 and CE-025. The city's road transport system is regulated by the Fortaleza Urban Transportation Company (ETUFOR), an agency of the Municipality of Fortaleza, while the transit of vehicles is supervised by the Municipal Authority of Transit, Public Services and Citizenship (AMC). The collective transport carried out by buses is called the Integrated Transportation System (SIT-FOR), and its operation began in 1992. The system provides the user with options of transportation and access to the different zones of the city through the integration of single tariff in terminals Regional authorities. The SIT-FOR network is based on three types of lines: those that integrate neighborhood-terminal, those that integrate the terminal to the center of the city or to another terminal.[106]

The system of traffic monitoring is known by the acronym CTAFOR,[105] which stands for "Controle de Tráfego em Área de Fortaleza" (Traffic Control of the Area of Fortaleza).

Subway

The Fortaleza Metro is operated by Companhia Cearense de Transportes Metropolitanos (Metrofor). Founded on May 2, 1997, the company is responsible for administration, construction and metro planning in Fortaleza and its metropolitan region. The system is headed by the Government of the State of Ceará and has as current president Eduardo Hotz.[107]

The Fortaleza Metro started on October 1, 2014. As of 2014 18 of the 20 stations planned for the South Line are in operation, along with 9 stations of the West Line.[108]

MetroFor is the 43 kilometres (27 mi) rapid transit system for the city of Fortaleza.[107]

Bus stations

Engenheiro João Tomé Bus station is the Fortaleza Bus terminal official name. Was Contstructed in 1973. It carries a daily average of over 8,000 passengers. 35 Bus companies and close to 200 bus lines. The bus station is centrally located within the city limits. Only 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) from the city centre and 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) from Praia de Iracema Beach. Fortaleza bus station is accessible by at least 2 city bus lines: Av. Borges de Melo I and Av. Borges de Melo II. Fortaleza has multiple Bus Rapid Transit, or BRT, lines throughout the city and has plans to extend this network of transportation (BRTBrasil.org)[109]

Bike lanes

Fortaleza officially has 116.4 kilometres (72.3 mi) of bike lanes.[110]

Public Transportation Statistics

The average person in Fortaleza spends 89 minutes riding public transit on a weekday, and 30% of public transit riders ride for more than 2 hours every day. People typically wait 24 minutes at a stop or station for public transit; on average, 52% of riders wait for over 20 minutes every day. The average distance people usually ride in a single trip with public transit is 6.8 km, while 10% travel for over 12 km in a single direction.[111]

Sports

The main games of the Ceará State Championship are played in Fortaleza. There are several association football clubs in the city, including Ceará SC, Fortaleza EC and Ferroviário AC. It was one of the host cities of the 2013 FIFA Confederations Cup and 2014 FIFA World Cup.

.jpg) Internal view of Arena Castelão

Internal view of Arena Castelão Kitesurfing at Futuro Beach

Kitesurfing at Futuro Beach.jpg) External view of Arena Castelão

External view of Arena Castelão

Notable people

- José de Alencar, famous writer from the 19th century

- Alberto Nepomuceno, famous composer from the 19th century

- Rachel de Queiroz, first female writer in Academia Brasileira de Letras

- André Diamant, international chess grandmaster

- Casimiro Montenegro Filho, founder of the Brazilian Air Force Aeronautical Technologic Institute - ITA

- Maurício Peixoto, mathematician, one of the founders of IMPA

- Gilberto Câmara, former director of Brazil's National Institute for Space Research (INPE)

- Hélder Câmara, Roman Catholic Archbishop nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize

- Castelo Branco, former president (1964–67)

- Karim Aïnouz, film director

- Ed Lincoln, musician and composer

- Shelda Bede, beach volleyball player and olympic medalist

- Raffael, professional footballer

- Ronny Araújo, professional footballer

- Mário Jardel, retired professional footballer

- Marcus Aurélio, mixed martial arts professional

- Wilson Gouveia, mixed martial arts professional

- Thiago Alves, mixed martial arts professional

- Hermes França, mixed martial arts professional

- Jorge Gurgel, mixed martial arts professional

- Heloneida Studart, writer, politician, women's rights advocate

International relations

Twin towns – Sister cities

Fortaleza is twinned with:

See also

References

- ↑ "Fortaleza é a quinta capital mais populosa e lidera a sétima maior região metropolitana - Ceará - O POVO Online". Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- 1 2 Garmany, Jeff (2011). "Situating Fortaleza: Urban space and uneven development in northeastern Brazil". Cities. Elsevier. 28 (1): 45–52. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2010.08.004.

- ↑ "Global city GDP 2013-2014". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on June 4, 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ↑ "Fortaleza Brazil Retreat 2012 – November 15 Mastermind Retreat". New Lifestyle Secrets. 2012-10-17. Retrieved 2018-02-28.

- 1 2 History of Fortaleza and Ceará at Fortaleza, Ceará site

- ↑ The Fortress of Nossa Senhora da Assunção at Fortaleza, Ceará site

- ↑ "Fortaleza". 2014 FIFA World Cup Brazil. FIFA. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- ↑ History of Fortaleza (in English)

- ↑ "Fortaleza Bio - Fortaleza Career". Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC)". December 13, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Define fortaleza - Dictionary and Thesaurus". Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Fortaleza". Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- 1 2 "Temperatura Máxima (°C)" (in Portuguese). Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology. 1961–1990. Archived from the original on May 5, 2014. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- 1 2 "Temperatura Mínima (°C)" (in Portuguese). Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology. 1961–1990. Archived from the original on May 5, 2014. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Precipitação Acumulada Mensal e Anual (mm)" (in Portuguese). Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology. 1961–1990. Archived from the original on May 5, 2014. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- 1 2 "Temperatura Média Compensada (°C)" (in Portuguese). Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology. 1961–1990. Archived from the original on May 5, 2014. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Umidade Relativa do Ar Média Compensada (%)". Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology. Archived from the original on May 5, 2014. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ↑ Dewar, Robert E. and Wallis, James R; ‘Geographical patterning of interannual rainfall variability in the tropics and near tropics: An L-moments approach’; in Journal of Climate, 12; pp. 3457-3466

- ↑ "Número de Dias com Precipitação Mayor ou Igual a 1 mm (dias)". Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology. Archived from the original on May 5, 2014. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ↑ "Insolação Total (horas)". Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology. Archived from the original on May 5, 2014. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ↑ "Temperatura Máxima Absoluta (ºC)". Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology (Inmet). Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ↑ "Temperatura Mínima Absoluta (ºC)". Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology (Inmet). Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ↑ Manguezal do Rio Ceará Archived September 11, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. (in Portuguese)

- ↑ Manguezal do Rio Cocó Archived November 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. (in Portuguese)

- ↑ Parque Estadual Marinho da Pedra da Risca do Meio, SEMACE, Governo do Estado do Ceará, archived from the original on November 29, 2016, retrieved November 28, 2016

- ↑ "Plano de gestão integrada da orla do município de Fortaleza" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Ministério do Meio Ambiente do Brasil. August 2006. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

- ↑ "Meio Ambiente". Anuário de Fortaleza 2012-2013. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ↑ "ARIE do Sítio Curió". SEMACE. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Unidades de conservação". Anuário de Fortaleza 2012-2013. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Lagoas de Fortaleza". Anuário de Fortaleza 2012-2013. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Corredor Ecológico do Rio Pacoti" (in Portuguese). SEMACE. Archived from the original on May 6, 2017. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- ↑ "Área de Proteção Ambiental do Estuário do Rio Ceará" (in Portuguese). SEMACE. Archived from the original on May 6, 2017. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

- ↑ 2010 IGBE Census Archived January 1, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. (in Portuguese)

- 1 2 2010 IGBE Census (in Portuguese)

- ↑ The largest Brazilian cities – 2010 IBGE Census (in Portuguese)

- ↑ "Fortaleza Ceara Brazil - travel information". Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ↑ Pena, Sérgio D. J.; Pietro, Giuliano Di; Fuchshuber-Moraes, Mateus; Genro, Julia Pasqualini; Hutz, Mara H.; Kehdy, Fernanda de Souza Gomes; Kohlrausch, Fabiana; Magno, Luiz Alexandre Viana; Montenegro, Raquel Carvalho; Moraes, Manoel Odorico; Moraes, Maria Elisabete Amaral de; Moraes, Milene Raiol de; Ojopi, Élida B.; Perini, Jamila A.; Racciopi, Clarice; Ribeiro-dos-Santos, Ândrea Kely Campos; Rios-Santos, Fabrício; Romano-Silva, Marco A.; Sortica, Vinicius A.; Suarez-Kurtz, Guilherme (February 16, 2011). "The Genomic Ancestry of Individuals from Different Geographical Regions of Brazil Is More Uniform Than Expected". PLOS ONE. 6 (2): e17063. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017063. PMC 3040205. PMID 21359226. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via PLoS Journals.

- ↑ Magalhães da Silva, Thiago; Sandhya Rani, M. R.; de Oliveira Costa, Gustavo Nunes; Figueiredo, Maria A.; Melo, Paulo S.; Nascimento, João F.; Molyneaux, Neil D.; Barreto, Maurício L.; Reis, Mitermayer G.; Teixeira, M. Glória; Blanton, Ronald E. (July 1, 2015). "The correlation between ancestry and color in two cities of Northeast Brazil with contrasting ethnic compositions". Eur J Hum Genet. 23 (7): 984–989. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2014.215. PMC 4463503. PMID 25293718. Retrieved December 10, 2016 – via www.nature.com.

- ↑ "Sistema IBGE de Recuperação Automática – SIDRA". Sidra.ibge.gov.br. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ↑ "População residente por cor ou raça e religião - Fortaleza". IBGE. Archived from the original on March 23, 2015. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Constituição do Brasil". Palácio do Planalto. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ↑ "Eleições 2012: Apuração: Fortaleza". G1. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ↑ "Fortaleza: Apuração do segundo turno". Uol. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ↑ "Fortaleza já conhece os 43 vereadores que ocuparão a Câmara Municipal". Diário do Nordeste. September 7, 2012. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ↑ "Lei Orgânica de Fortaleza". CMFOR. 2012. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ↑ "Perfil dos municípios brasileiros - Fortaleza". IBGE. 2013. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ↑ "No Ceará, Camilo Santana sucede padrinho político e ministro Cid". G1. 1 January 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ↑ "Palácio Iracema". Governo do Estado do Ceará. April 25, 2011. Archived from the original on August 2, 2017. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ↑ "Governo do Estado do Ceará, Secretários e Órgãos vinculados". Governo do Estado do Ceará. Archived from the original on 5 April 2010. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ↑ "Faça a diferença". Catraca Livre. 22 July 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ↑ "Fortaleza". Mercociudades. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ↑ "Produto Interno Bruto dos Municípios 1999-2002". IBGE. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ↑ "Posição ocupada pelos 100 maiores municípios, em relação ao Produto Interno Bruto" (PDF). IBGE. 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- 1 2 "Produto interno bruto dos municípios - 2012". IBGE. 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ↑ "IPC Maps 2014" (PDF). IPC Marketing. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 8, 2014. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ↑ "Estatísticas do cadastro central de empresas - 2012". IBGE. 2012. Archived from the original on January 23, 2017. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ↑ "Zonas de preservação do patrimônio". O Povo. 24 November 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ↑ "Patrimônio Histórico e Cultural". Prefeitura Municipal de Fortaleza. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Histórico dos Bens Tombados". Prefeitura Municipal de Fortaleza. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Políticas públicas contemplam mestres da cultura". Portal Brasil. 4 June 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ↑ "Palco para todas as artes". Diário do Nordeste. 9 March 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ "Fortaleza. Cronologia da Cidade". Revista Fale!. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ "Centro Dragão do Mar de Arte e Cultura". Governo do Estado do Ceará. 31 July 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ "Os museus e a memória da literatura brasileira" (PDF). Instituto Brasileiro de Museus. 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ↑ "Casa de José de Alencar" (PDF). Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ↑ "Rede Cuca comemora aniversário com programação especial". O Povo. 20 February 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ↑ "Clubes inovam para atrair público". Diário do Nordeste. 9 June 2012. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ↑ "Artesanato" (in Portuguese). Governo do Estado do Ceará. Archived from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- ↑ Gilmar de Carvalho. "Letras sob o sol e o areal". Folha de S. Paulo. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ↑ Luciana Brito (2012). "Presença da Padaria Espiritual na História da Imprensa e das Artes no Ceará". Unesp.

- ↑ "Academia Cearense de Letras: nova aos 120 anos". O Estado. 29 August 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ↑ "Batista de Lima". Diário do Nordeste. 13 July 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ↑ "A vez dos cearenses". Folha de S. Paulo. 11 January 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ↑ "Principais festivais de cinema formam uma frente". Revista de Cinema. 16 November 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ↑ "Santo de casa faz milagre". Diário do Nordeste. 19 April 2008. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- ↑ Andressa Zanandrea. "Dragão Fashion Brasil - dia 1". IG. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ↑ "Linhas íntimas". Tribuna do Ceará. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ Jomar Morais (January 1, 2000). "Alma de mascate". Info Exame. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Para pesquisador, forró eletrônico renova a tradição". Diário do Nordeste. 10 November 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ "Fortaleza". February 7, 2014. Archived from the original on November 23, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Sabores da culinária regional". Diário do Nordeste. 26 August 2005. Archived from the original on 5 February 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ↑ "9 restaurantes para comer bem em Fortaleza". Guia Quatro Rodas. 29 August 2012. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ↑ "Fortaleza". UOL Viagem. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ↑ "Projeto custou R$ 1,8 milhão, diz arquiteto". o Povo. 25 April 2012. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ↑ "Slowing the Pace Along Brazil's Coast". New York Times. 20 February 2005. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ↑ Soares, Marcelo de Oliveira; Paiva, Carolina Cerqueira de; Freitas, João Eduardo Pereira de; Lotufo, Tito Monteiro da Cruz (2011), "Gestão de unidades de conservação marinhas: o caso do Parque Estadual Marinho da Pedra da Risca do Meio, NE – Brasil" (PDF), Revista da Gestão Costeira Integrada, 11 (2), retrieved 2016-11-28

- ↑ patrick (January 27, 2012). "Praia de Iracema". Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Mucuripe, Fortaleza - Veja dicas no Férias Brasil". Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ↑ Atlas do Desenvolvimento Humano do Brasil 2013 (2010). "Perfil do município de Fortaleza no Atlas do IDH 2013". Programa das Nações Unidas para o Desenvolvimento (PNUD). Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ↑ "Fortaleza - CE". Acompanhamento Brasileiro dos Objetivos de Desenvolvimento do Milênio. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ↑ DATASUS (10 April 2010). "Caderno de Informações de Saúde - Informações Gerais". Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ↑ "UPAs". Secretaria Municipal da Saúde. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- ↑ "Onde ficam os novos CEOs, policlínicas, UPAs e hospitais". Secretaria da Saúde do Estado. 15 July 2013. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ↑ "Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Fortaleza comemora 150 anos". Diário do Nordeste. 20 February 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ↑ "Os Maiores Hospitais Privados". Anuário de Fortaleza 2012-2013 (Fundação Demócrito Rocha). Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ↑ "Farmácia Popular". Secretaria Municipal de Saúde. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- ↑ "Fortaleza é a 3ª capital do Brasil com maior cobertura do Programa Saúde da Família". Diário do Nordeste. 25 July 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ↑ "SAMU 192 -Fortaleza". Secretaria Municipal de Saúde. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ↑ "HUWC é o maior centro de transplantes de fígado da América Latina". Verdes Mares. 27 February 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ↑ "Medicina na Federal do Ceará é o curso mais concorrido do Sisu". Estadão. 8 January 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ↑ Wellington Ricardo Nogueira Maciel (2006). "Aeroporto de Fortaleza: usos e significados contemporâneos" (PDF). UFC. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ↑ "Infraero lança edital para conclusão de obras do aeroporto de Fortaleza". G1. 6 January 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ↑ "Movimento Operacional da Rede Infraero de Janeiro a Dezembro de 2013" (PDF). Infraero. 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ↑ Fernanda Castello Branco. "As 11 estradas mais incríveis do Brasil". iG. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Autarquia Municipal de Trânsito". CTAFOR. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 9, 2014.

- ↑ "Integração no sistema de transporte público coletivo de Fortaleza" (PDF). Câmara Municipal de Fortaleza. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- 1 2 "Mapa das Linhas - Metrô de Fortaleza". Metrô de Fortaleza - METROFOR. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- ↑ "Dilma cita metrô de Fortaleza em debate e causa polêmica nas redes sociais". Rádio Verdes Mares. 20 October 2014. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ↑ "BRT Brasil". Associação Nacional das Empresas de Transportes - NTU. Retrieved 2015-01-29.

- ↑ "Prefeitos planejam dobrar ciclovias em capitais até 2016 - 15/04/2015 - Cotidiano - Folha de S.Paulo". Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Fortaleza Public Transportation Statistics". Global Public Transit Index by Moovit. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- ↑ "Pragmatismo marca gestão de Luizianne em Fortaleza". Clipping do Ministério do Planejamento. 17 April 2007. Archived from the original on 27 November 2012. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ↑ "Sister City of Miami Beach — City Commission Meeting". City of Miami Beach. May 26, 2004. Archived from the original on June 27, 2013. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ↑ "Fortaleza se torna cidade irmã de Lisboa". Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ↑ "La Força Expedicionária Brasileira — F.E.B". MUSEO STORICO DI MONTESE. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ↑ "Lei 9083 Considera Cidade Irmã de Fortaleza a cidade de Natal" (PDF). Diário Oficial do Município de Fortaleza. 1 June 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 3, 2007. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ↑ "Praia gemina-se com Fortaleza no seu 150º aniversário". Embaixador de Cabo Verde em Brasília. 29 April 2008. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ↑ "Online Directory: Brazil, Americas". Sister Cities International. 2008. Archived from the original on April 16, 2008. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ↑ "O 1º Intercâmbio Econômico e Cultural Afro-Brasileiro possibilita negócios entre Senegal e Ceará". APRECE. 2006. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

Bibliography

External links

- (in Portuguese) Fortaleza City Council home page

- (in Portuguese) Fortaleza Tourism Office home page

_1.jpg)