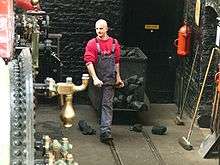

Fireman (steam engine)

Fireman or stoker is the job title for someone whose job is to tend the fire for the running of a boiler, to heat a building, power a steam engine, etc. On steam locomotives the term fireman is usually used, while on steamships and stationary steam engines, such as those driving saw mills, the term is usually stoker (although the British Merchant Navy did use fireman). The German word Heizer is equivalent and in Dutch the word stoker is mostly used too. The United States Navy referred to them as watertenders. Much of the job is hard physical labor, such as shoveling fuel, typically coal, into the boiler's firebox.[1]

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy used the rank structure ordinary stoker, stoker, leading stoker, stoker petty officer and chief stoker. The non-substantive (trade) badge for stokers was a ship's propeller. Stoker remains the colloquial term used to refer to a marine engineering rating, despite the decommissioning of the last steam-powered naval vessel many years ago.

Large coal-fueled vessels also had individuals working as coal trimmers, who delivered coal from the coal bunkers to the stokers. They were responsible for all coal handling with the exception of the actual fueling of the boilers.

Royal Canadian Navy

The Royal Canadian Navy had steam powered ships, the last of which were replenishment ships. All marine engineers in the RCN, regardless of their platform (CPF, 280 or AOR) are nicknamed stokers.

Railways

On steam locomotives, firemen were not usually responsible for initially preparing locomotives and lighting their fires. As a locomotive boiler takes several hours to heat up, and a too-rapid fire-raising can cause excess wear on a boiler, this task was usually performed by fire lighters working some hours before the fireman's main shift started. Only on small railways, or on narrow-gauge locomotives with smaller and faster-warming boilers, was the fire lit by the fireman.

Whoever was responsible for fire-starting would clear the ash from the firebox ashpan prior to lighting the fire, adding water to the engine's boiler, making sure there is a proper supply of fuel for the engine aboard before starting journeys, starting the fire, raising or banking the fire as appropriate for the amount of power needed along particular parts of the route, and performing other tasks for maintaining the locomotive according to the orders of the engineer (US) or driver (UK). The engine itself was cleaned by an engine cleaner instead of the fireman.[1] Some firemen served these duties as a form of apprenticeship, aspiring to be locomotive engineers themselves. In the present day, the position of fireman still exists on the Union Pacific Railroad, but it refers to an engineer in training. The fireman may operate the locomotive under the direct supervision of the engineer. When the fireman is not operating the locomotive, the fireman assists the engineer and monitors the controls. [2]

Mechanical stoker

A mechanical stoker is a device which feeds coal into the firebox of a boiler. It is standard equipment on large stationary boilers and was also fitted to large steam locomotives to ease the burden of the fireman. The locomotive type has a screw conveyor (driven by an auxiliary steam engine) which feeds the coal into the firebox. The coal is then distributed across the grate by steam jets, controlled by the fireman. Power stations usually use pulverized coal-fired boilers.

Notable stokers

There were approximately 176 stokers on board the coal fed ocean liner RMS Titanic. During the sinking of the ship, these men disregarded their own safety and stayed below deck to keep the steam driven electric generators running for the radiotelegraph, lighting, and water pumps.[3][4][5] Only 48 of them survived.[6]

Simeon T. Webb was the fireman on the Cannonball Express when it was destroyed in the legendary wreck that killed engineer Casey Jones. Jones's last words were "Jump, Sim, jump!" and Webb did jump, survived, and became a primary source for information about the famous wreck.[7][8]

KFC founder Colonel Sanders worked as a railroad stoker when he was 16 or 17.[9]

A 14-year old Martin Luther King Sr. worked as a fireman on the Atlanta railroad. [10]

Depictions in popular culture and art

Art

- Torsten Billman, a Swedish graphic artist, drawer, and mural painter - himself coal trimmer and stoker on various merchant ships from 1926 to 1932 - has portrayed the hard work in coal bunkers and stokeholes.

Events

- Top Gear's Jeremy Clarkson acted as stoker on the steam locomotive No. 60163 Tornado while performing a Race to the North against Richard Hammond and James May. It was an homage to the historical Race to the North, a rivalry between British steam engines, trains and men of different companies between London and Edinburgh.

Film

- The lead character Bill Roberts (George Bancroft) in Josef von Sternberg's motion picture The Docks of New York (1928) is a stoker.

Literature

- The first chapter of Franz Kafka's novel Amerika (published posthumously in 1927) is entitled "The Stoker".

- Mat Burke, a principal role in Eugene O'Neill's play Anna Christie (1921) is a ship's stoker.

- Yank, the protagonist of Eugene O'Neill's play The Hairy Ape (1922), is a stoker on a ship.

Music

- "Stoker Dreams" and "Stoker Love" are songs by the Russian indie group Chimera.

References

- 1 2 "Little and Often" 1947 training video on YouTube. Firing A Steam Locomotive, 1947 Educational Documentary for WDTV LIVE42, West Virginia.

- ↑ "UP:Past and Present Job Descriptions".

- ↑ Gill, Anton (2010). Titanic : the real story of the construction of the world's most famous ship. Channel 4 Books. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-905026-71-5.

- ↑ "Titanic Sinking Engine Room Heroes". gendisasters.com.

- ↑ "Titanic". UCO.es. p. 1.

- ↑ Crew of the RMS Titanic#Engineering crew

- ↑ "The Historic Casey Jones Home & Railroad Museum in Jackson, Tennessee – Celebrating 50 Legendary Years! 1956-2006". Casey Jones Home & Railroad Museum. Archived from the original on May 28, 2006. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

- ↑ Hubbard, Freeman (1945). Railroad Avenue. McGraw Hill.

- ↑ Sanders, Harland (2012). The Autobiography of the Original Celebrity Chef (PDF). Louisville: KFC. ISBN 978-0-9855439-0-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 21, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ↑ King Sr., Reverend Martin Luther (1980). Daddy King. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press. pp. 42–45. ISBN 9780807097762.

Further reading

- "Titanic's unsinkable stoker". BBC News. Northern Ireland. March 30, 2012.

- Huibregtse, Jon R. (2010). American Railroad Labor and the Genesis of the New Deal, 1919-1935. University Press of Florida.

- Walter Licht (1983). Working for the Railroad: the organization of work in the nineteenth century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Orr, John W. (2001). Set Up Running: The Life of a Pennsylvania Railroad Engineman, 1904-1949. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Tuck, Joseph Hugh (1976). Canadian Railways and the International Brotherhoods: Labour Organizations in the Railway Running Trades in Canada, 1865-1914. University of Western Ontario. Dissertation.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stokers. |