Fatimid Caliphate

| Fatimid Caliphate الخلافة الفاطمية Al-Khilafah al-Fāṭimiyya | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 909–1171 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

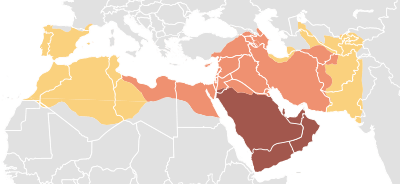

Evolution of the Fatimid state | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Islam (Ismaili Shia) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Caliphate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Caliph | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 909–934 (first) | al-Mahdi Billah | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1160–1171 (last) | al-'Āḍid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Early Middle Ages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Established | 5 January 909 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Foundation of Cairo | 8 August 969 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1171 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 969[2][3] | 4,100,000 km2 (1,600,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Dinar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Caliphate خِلافة |

|---|

|

|

Main caliphates |

|

Parallel caliphates |

|

|

| Historical Arab states and dynasties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ancient Arab States

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Eastern Dynasties

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Western Dynasties

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Arabian Peninsula

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Current monarchies

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Islamic caliphate that spanned a large area of North Africa, from the Red Sea in the east to the Atlantic Ocean in the west. The dynasty of Arab origin[4] ruled across the Mediterranean coast of Africa and ultimately made Egypt the centre of the caliphate. At its height the caliphate included in addition to Egypt varying areas of the Maghreb, Sudan, Sicily, the Levant, and Hijaz.

The Fatimids (Arabic: الفاطميون, translit. al-Fāṭimīyūn) claimed descent from Fatimah, the daughter of Islamic prophet Muhammad. The Fatimid state took shape among the Kutama Berbers, in the West of the North African littoral, in Algeria, in 909 conquering Raqqada, the Aghlabid capital. In 921 the Fatimids established the Tunisian city of Mahdia as their new capital. In 948 they shifted their capital to Al-Mansuriya, near Kairouan in Tunisia. In 969 they conquered Egypt and established Cairo as the capital of their caliphate; Egypt became the political, cultural, and religious centre of their empire that developed an indigenous Arabic culture.[5]

The ruling class belonged to the Ismaili branch of Shi'ism, as did the leaders of the dynasty. The existence of the caliphate marked the only time the descendants of Ali and Fatimah were united to any degree (except for the final period of the Rashidun Caliphate under Ali himself from 656 to 661) and the name "Fatimid" refers to Fatimah. The different term Fatimite is sometimes used to refer to the caliphate's subjects.

After the initial conquests, the caliphate often allowed a degree of religious tolerance towards non-Ismaili sects of Islam, as well as to Jews, Maltese Christians, and Egyptian Coptic Christians.[6] However, its leaders made little headway in persuading the Egyptian population to adopt its religious beliefs.[7]

During the late eleventh and twelfth centuries the Fatimid caliphate declined rapidly, and in 1171 Saladin invaded its territory. He founded the Ayyubid dynasty and incorporated the Fatimid state into the Abbasid Caliphate.[8]

Rise of the Fatimids

Isma‘ilism |

|---|

|

|

Branches / sects

States / region People

Others |

|

|

|

|

Origins

The Fatimid Caliphate's religious ideology originated in an Ismaili Shia movement launched in the 9th century in Salamiyah, Syria by the eighth Ismaili Imam, Abd Allah al-Akbar[9] (766-828). He claimed descent through Ismail, the seventh Ismaili Imam, from Fatimah and her husband ‘Alī ibn-Abī-Tālib, the first Shī‘a Imām, whence his name al-Fātimī "the Fatimid".[10] The eighth to tenth Ismaili Imams, (Abadullah, Ahmed (c. 813-c. 840) and Husain (died 881)), remained hidden and worked for the movement against the rulers of the period.

Together with his son, the 11th Imam Abdullah al-Mahdi Billah (lived 873-934), in the guise of a merchant, made his way to Sijilmasa,[9] in present-day Morocco, fleeing persecution by the Abbasids, who found their Isma'ili Shi'ite beliefs not only unorthodox, but also threatening to the status quo of their caliphate. According to legend, 'Abdullah and his son were fulfilling a prophecy that the mahdi would come from Mesopotamia to Sijilmasa. They hid among the population of Sijilmasa, then an independent emirate, ruled by Prince Yasa' ibn Midrar (r. 884-909).[9]

The dedicated Shi'ite Abu Abdallah al-Shi'i supported Al-Mahdi. Al-Shi'i started his preaching after he encountered a group of Muslim North African during his hajj. These men bragged about the country of the Kutama in western Ifriqiya (today part of Algeria), and the hostility of the Kutama towards, and their complete independence from, the Aghlabid rulers. This triggered al-Shi'i to travel to the region, where he started to preach the Ismaili doctrine. The Berber peasants, oppressed for decades under the corrupt Aghlabid rule, would prove themselves to be a perfect basis for sedition. Rapidly, al-Shi'i began conquering cities in the region: first Mila, then Sétif, Kairouan, and eventually Raqqada, the Aghlabid capital. In 909 Al-Shi'i sent a large expedition force to rescue the Mahdi, conquering the Khariji state of Tahert on its way there. After gaining his freedom, Abdullah al-Mahdi Billah became the leader of the growing state and assumed the position of imam and caliph.

Expansion

Abdullāh al-Mahdi's control soon extended over all of the Maghreb, an area consisting of the modern countries of Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya,[11] which he ruled from Mahdia. The newly built city of Al-Mansuriya,[lower-alpha 1] or Mansuriyya (Template:Lang-arالمنصورية), near Kairouan, Tunisia, was the capital of the Fatimid Caliphate during the rule of the Imams Al-Mansur Billah (r. 946–953) and Al-Mu'izz li-Din Allah (r. 953–975).

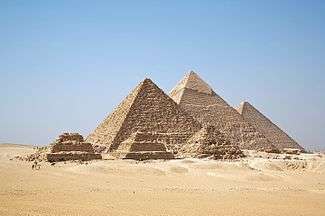

The Fatimid general Jawhar conquered Egypt in 969, where he built a new palace city, near Fusṭāt, which he also called al-Manṣūriyya. Under Al-Mu'izz li-Din Allah, the Fatimids conquered the Ikhshidid Wilayah (see Fatimid Egypt), founding a new capital at al-Qāhira (Cairo) in 969.[13] The name was a reference to the planet Mars, "The Subduer",[10] which was prominent in the sky at the moment that city construction started. Cairo was intended as a royal enclosure for the Fatimid caliph and his army, though the actual administrative and economic capital of Egypt was in cities such as Fustat until 1169. After Egypt, the Fatimids continued to conquer the surrounding areas until they ruled from Tunisia to Syria, as well as Sicily.

Under the Fatimids, Egypt became the centre of an empire that included at its peak parts of North Africa, Sicily, Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, the Red Sea coast of Africa, Tihamah, Hejaz, and Yemen. Egypt flourished, and the Fatimids developed an extensive trade network in both the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean. Their trade and diplomatic ties extended all the way to China and its Song Dynasty, which eventually determined the economic course of Egypt during the High Middle Ages. The Fatimid focus on long-distance trade was accompanied by a lack of interest in agriculture and a neglect of the Nile irrigation system.[10]

Capitals

Al-Mahdiyya, the first capital of the Fatimid dynasty, was established by the first caliph of the Fatimid dynasty, ʿAbdullāh al-Mahdī (297–322/909–934) in 300/912–913. The caliph had been residing in nearby Raqqada but chose a new and more strategic location to establish his dynasty. The city of al-Mahdiyya is located on a narrow peninsula along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, east of Kairouan and just south of the Gulf of Hammamet in modern-day Tunisia. The primary concern in the city's construction and locale was defense. With its peninsular topography and the construction of a wall 8.3 m thick, the city became impenetrable by land. This strategic location together with a navy that the Fatimids had inherited from the conquered Aghlabids, the city of Al-Mahdiyya became a strong military base where ʿAbdullāh al-Mahdī consolidated power and established the roots of the Fatimid caliphate for two generations. The city included two royal palaces — one for the caliph ‘Abdullāh al-Mahdī and one for his son and successor the caliph al-Qāʾim — a mosque, many administrative buildings, and an arsenal.[14]

Al-Manṣūriyya was established between 334 and 336/945-8 by the third Fatimid caliph al-Manṣūr (334-41/946-53) in a settlement known as Ṣabra, located on the outskirts of Kairouan in modern-day Tunisia. The new capital was established in commemoration of the victory of al-Manṣūr over the Khārijite rebel Abū Yazīd at Ṣabra. Like Baghdad, the plan of the city of Al-Manṣūriyya is round, with the caliphal palace at its center. Due to a plentiful water source, the city grew and expanded a great deal under al-Manṣūr. Recent archaeological evidence suggests that there were more than 300 ḥammāms built during this period in the city as well as numerous palaces. When al-Manṣūr’s successor, al-Muʿizz moved the caliphate to Cairo, his deputy stayed behind as regent of al-Manṣūriyya and usurped power for himself, marking the end of the Fatimid reign in al-Manṣūriyya and the beginning of the city’s ruin (spurred on by a violent revolt). The city remained downtrodden and more or less uninhabited for centuries afterward.[15]

Cairo was established by the fourth Fatimid caliph al-Muʿizz in 359/970 and remained the capital of the Fatimid caliphate for the duration of the dynasty. Cairo can thus be considered the capital of Fatimid cultural production. Though the original Fatimid palace complex, including administrative buildings and royal residents, no longer exists, modern scholars can glean a good idea of the original structure based on the Mamluk-era account of al-Maqrīzī. Perhaps the most important of Fatimid monuments outside the palace complex is the mosque of al-Azhar (359-61/970-2) which still stands today, though little of the building is original to its first Fatimid construction. Likewise the important Fatimid mosque of al-Ḥākim, built from 380-403/990-1012 under two Fatimid caliphs, has been rebuilt under subsequent dynasties. Cairo remained the capital for, including al-Muʿizz, eleven generations of caliphs, after which the Fatimid Caliphate finally fell to Ayyubid forces in 567/1171.[16]

Administration and culture

Unlike western European governments in the era, advancement in Fatimid state offices was more meritocratic than based on heredity. Members of other branches of Islam, like the Sunnis, were just as likely to be appointed to government posts as Shiites. Tolerance was extended to non-Muslims such as Christians and Jews,[10] who occupied high levels in government based on ability, and tolerance was set into place to ensure the flow of money from all those who were non-Muslims in order to finance the Caliphs' large army of Mamluks brought in from Circassia by Genoese merchants. There were exceptions to this general attitude of tolerance, however, most notably by Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, though this has been highly debated, with Al-Hakim's reputation among medieval Muslim historians conflated with his role in the Druze faith.[10]

The Fatimids were also known for their exquisite arts. A type of ceramic, lustreware, was prevalent during the Fatimid period. Glassware and metalworking was also popular. Many traces of Fatimid architecture exist in Cairo today; the most defining examples include the Al-Azhar University and the Al-Hakim Mosque. The madrasa is one of the relics of the Fatimid dynasty era of Egypt, descended from Fatimah, daughter of Muhammad. Fatimah was called Az-Zahra (the brilliant), and the madrasa was named in her honour.[17] It was founded as a mosque by the Fatimid commander Jawhar at the orders of the Caliph Al-Muizz when he founded the city of Cairo. It was (probably on Saturday) in Jamadi al-Awwal in the year 359 A.H. Its building was completed on the 9th of Ramadan in the year 361 A.H. Both Al-'Aziz Billah and Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah added to its premises. It was further repaired, renovated, and extended by Al-Mustansir Billah and Al-Hafiz Li-Din-illah. Fatimid Caliphs always encouraged scholars and jurists to have their study-circles and gatherings in this mosque, and thus it was turned into a university that has the claim to be considered as the oldest still-functioning University.[18]

Intellectual life in Egypt during the Fatimid period achieved great progress and activity, due to many scholars who lived in or came to Egypt, as well as the number of books available. Fatimid Caliphs gave prominent positions to scholars in their courts, encouraged students, and established libraries in their palaces, so that scholars might expand their knowledge and reap benefits from the work of their predecessors.[18]

Perhaps the most significant feature of Fatimid rule was the freedom of thought and reason extended to the people, who could believe in whatever they liked, provided they did not infringe on the rights of others. Fatimids reserved separate pulpits for different Islamic sects, where the scholars expressed their ideas in whatever manner they liked. Fatimids gave patronage to scholars and invited them from every place, spending money on them even when their beliefs conflicted with those of the Fatimids.[18]

The Fatimid palace in Cairo had two parts. It stood in the Khan el-Khalili area at Bayn El-Qasryn street.[19]

Fatimid dynasty

- Abū Muḥammad 'Abdul-Lāh al-Mahdī bi'llāh (909–934) founder Fatimid dynasty

- Abū l-Qāsim Muḥammad al-Qā'im bi-Amr Allāh (934–946)

- Abū Ṭāhir Ismā'il al-Manṣūr bi-llāh (946–953)

- Abū Tamīm Ma'add al-Mu'izz li-Dīn Allāh (953–975) Egypt is conquered during his reign

- Abū Manṣūr Nizār al-'Azīz bi-llāh (975–996)

- Abū 'Alī al-Manṣūr al-Ḥākim bi-Amr Allāh (996–1021) The Druze religion is founded during the lifetime of Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah.

- Abū'l-Ḥasan 'Alī al-Ẓāhir li-I'zāz Dīn Allāh (1021–1036)

- Abū Tamīm Ma'add al-Mustanṣir bi-llāh (1036–1094)

- al-Musta'lī bi-llāh (1094–1101) Quarrels over his succession led to the Nizari split.

- Abū 'Alī Mansur al-Āmir bi-Aḥkām Allāh (1101–1130) The Fatimid rulers of Egypt after him are not recognized as Imams by Mustaali/Taiyabi Ismailis.

- 'Abd al-Majīd al-Ḥāfiẓ (1130–1149) The Hafizi sect is founded with Al-Hafiz as Imam.

- al-Ẓāfir (1149–1154)

- al-Fā'iz (1154–1160)

- al-'Āḍid (1160–1171)[20]

Burial places

There is the place known as "Al-Mashhad al-Hussaini" (Masjid Imam Husain, Cairo), wherein lie buried underground Twelve Fatimid Imams from 9th Taqi Muhammad to 20th Mansur al-Āmir. This place is also known as "Bāb Mukhallafāt al-Rasul" (door of remaining part of Rasul), where Sacred Hair [21][22] of Muhammad is preserved.

Military system

The Fatimid military was based largely on the Kutama Berber tribesmen brought along on the march to Egypt, and they remained an important part of the military even after Tunisia began to break away.[23] After their successful establishment in Egypt, local Egyptian forces were also incorporated into the army, so the Fatimid Army were reinforced by North African soldiers from Algeria to Egypt in the Eastern North. (and of succeeding dynasties as well).

A fundamental change occurred when the Fatimid Caliph attempted to push into Syria in the latter half of the 10th century. The Fatimids were faced with the now Turkish-dominated forces of the Abbasid Caliph and began to realize the limits of their current military. Thus during the reign of Abu Mansur Nizar al-Aziz Billah and Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, the Caliph began incorporating armies of Turks and later black Africans (even later, other groups such as Armenians were also used).[24] The army units were generally separated along ethnic lines, thus the Berbers were usually the light cavalry and foot skirmishers, while the Turks were the horse archers or heavy cavalry (known as Mamluks). The black Africans, Syrians, and Arabs generally acted as the heavy infantry and foot archers. This ethnic-based army system, along with the partial slave status of many of the imported ethnic fighters, would remain fundamentally unchanged in Egypt for many centuries after the fall of the Fatimid Caliph.

The Fatimids put all their military power toward the defence of the empire whenever it was menaced by dangers and threats, which they were able to repel, especially during the rule of Al-Muizz Lideenillah. During his reign, the Byzantine Empire was ruled by Nikephoros II Phokas, who had destroyed the Muslim Emirate of Chandax in 961 and conquered Tartus, Al-Masaisah, 'Ain Zarbah, and other places, gaining complete control of Iraq and the Syrian borders as well as earning the sobriquet, the "Pale Death of the Saracens". With the Fatimids, however, he proved less successful. After renouncing his payments of tribute to the Fatimid caliphs, he sent an expedition to Sicily, but was forced by defeats on land and sea to evacuate the island completely. In 967, he made peace with the Fatimids and turned to defend himself against their common enemy, Otto I, who had proclaimed himself Roman Emperor and had attacked Byzantine possessions in Italy.

Decline

.jpg)

While the ethnic-based army was generally successful on the battlefield, it began to have negative effects on Fatimid internal politics. Traditionally the Berber element of the army had the strongest sway over political affairs, but as the Turkish element grew more powerful, it began to challenge this, and by 1020 serious riots had begun to break out among the Black African troops who were fighting back against a Berber-Turk Alliance.

By the 1060s, the tentative balance between the different ethnic groups within the Fatimid army collapsed as Egypt suffered an extended period of drought and famine. Declining resources accelerated the problems among the different ethnic factions, and outright civil war began, primarily between the Turks under Nasir al-Dawla ibn Hamdan and Black African troops, while the Berbers shifted alliance between the two sides.[25] The Turkish forces of the Fatimid army seized most of Cairo and held the city and Caliph at ransom, while the Berber troops and remaining Sudanese forces roamed the other parts of Egypt.

By 1072, in a desperate attempt to save Egypt, the Fatimid Caliph Abū Tamīm Ma'ad al-Mustansir Billah recalled general Badr al-Jamali, who was at the time the governor of Acre, Palestine. Badr al-Jamali led his troops into Egypt and was able to successfully suppress the different groups of the rebelling armies, largely purging the Turks in the process. Although the Caliphate was saved from immediate destruction, the decade long rebellion devastated Egypt and it was never able to regain much power. As a result, Badr al-Jamali was also made the vizier of the Fatimid caliph, becoming one of the first military viziers ("Amir al Juyush", Arabic: امير الجيوش, Commander of Forces of the Fatimids) who would dominate late Fatimid politics. Al-Jam`e Al-Juyushi (Arabic: الجامع الجيوشي, The Mosque of the Armies), or Juyushi Mosque, was built by Badr al-Jamali. The mosque was completed in 478 H/1085 AD under the patronage of then Caliph and Imam Ma'ad al-Mustansir Billah. It was built on an end of the Mokattam Hills, ensuring a view of the Cairo city.[26] This Mosque/mashhad was also known as a victory monument commemorating vizier Badr's restoration of order for the Imam Mustansir.[27] As the military viziers effectively became heads of state, the Caliph himself was reduced to the role of a figurehead. Badr al-Jamali's son, Al-Afdal Shahanshah, succeeded him in power as vizier.

In the 1040s, the Berber Zirids (governors of North Africa under the Fatimids) declared their independence from the Fatimids and their recognition of the Sunni Abbasid caliphs of Baghdad, which led the Fatimids to launch the devastating Banū Hilal invasions of North Africa. After about 1070, the Fatimid hold on the Levant coast and parts of Syria was challenged first by Turkic invasions, then the Crusades, so that Fatimid territory shrank until it consisted only of Egypt. The Fatimids gradually lost the Emirate of Sicily over thirty years to the Italo-Norman Roger I who was in total control of the entire island by 1091.

The reliance on the Iqta system also ate into Fatimid central authority, as more and more the military officers at the further ends of the empire became semi-independent.

After the decay of the Fatimid political system in the 1160s, the Zengid ruler Nūr ad-Dīn had his general, Shirkuh, seize Egypt from the vizier Shawar in 1169. Shirkuh died two months after taking power, and rule passed to his nephew, Saladin.[28] This began the Ayyubid Sultanate of Egypt and Syria.

Legacy

After Al-Mustansir Billah, his sons Nizar and Al-Musta'li both claimed the right to rule, leading to a split in Nizari and Musta'li factions respectively. Nizar's successors eventually came to be known as 'Aga Khan.While Musta'li's followers eventually came to be called as Dawoodi bohra

The Fatimid dynasty continued under Al-Musta'li until Al-Amir bi-Ahkami'l-Lah's death in 1132. Leadership was then contested between At-Tayyib Abu'l-Qasim, Al-Amir's two-year-old son, and Al-Hafiz, Al-Amir's cousin whose supporters (Hafizi) claimed Al-Amir died without an heir. The supporters of At-Tayyib became the Tayyibi Isma'ilis. At-Tayyib's claim to the imamate was endorsed by Arwa al-Sulayhi, Queen of Yemen. In 1084, Al-Mustansir had designated Arwa designated a hujjah (a holy, pious lady), the highest rank in the Yemeni Da'wah. Under Arwa, the Da'i al-Balagh (the imam's local representative) Lamak ibn Malik and then Yahya ibn Lamak worked for the cause of the Fatimids. After At-Tayyib's disappearance, Arwa named Dhu'ayb bin Musa the first Da'i al-Mutlaq with full authority over Tayyibi religious matters. Tayyibi Isma'ili missionaries (in about 1067 AD(460AH)) spread their religion to India,[29][30] leading to the development of various Isma'ili communities, most notably the Alavi, Dawoodi, and Sulaymani Bohras. Syedi Nuruddin to Dongaon went to look after India's southern part and Syedi Fakhruddin to East Rajasthan.[31][32]

See also

References

- Notes

- ↑ Hathaway, Jane (2012). A Tale of Two Factions: Myth, Memory, and Identity in Ottoman Egypt and Yemen. SUNY Press. p. 97. ISBN 9780791486108.

- ↑ Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D (December 2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of world-systems research. 12 (2): 222. ISSN 1076-156X. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ Rein Taagepera (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 495. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ Ilahiane, Hsain (2004). Ethnicities, Community Making, and Agrarian Change: The Political Ecology of a Moroccan Oasis. University Press of America. p. 43. ISBN 9780761828761.

- ↑ Abbasid Belles Lettres. Cambridge University Press; 30 March 1990. ISBN 978-0-521-24016-1. p. 13.

- ↑ Wintle, Justin (May 2003). History of Islam. London: Rough Guides Ltd. pp. 136–7. ISBN 1-84353-018-X.

- ↑ Pollard;Rosenberg;Tignor, Elizabeth;Clifford;Robert (2011). Worlds together Worlds Apart. New York, New York: Norton. p. 313. ISBN 9780393918472.

- ↑ Baer, Eva (1983). Metalwork in Medieval Islamic Art. SUNY Press. p. xxiii. ISBN 9780791495575.

In the course of the later eleventh and twelfth century, however, the Fatimid caliphate declined rapidly, and in 1171 the country was invaded by Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn, the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. He restored Egypt as a political power, reincorporated it in the Abbasid caliphate and established Ayyubid suzerainty not only over Egypt and Syria but, as mentioned above, temporarily over northern Mesopotamia as well.

- 1 2 3 Yeomans 2006, p. 43.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Goldschmidt 84-86

- ↑ Yeomans 2006, p. 44.

- ↑ Tracy 2000, p. 234.

- ↑ Beeson, Irene (September–October 1969). "Cairo, a Millennial". Saudi Aramco World: 24, 26–30. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 9 August 2007.

- ↑ Talbi, M., “al-Mahdiyya”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W. P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 24 April 2017

- ↑ Talbi, M., "Ṣabra or al-Manṣūriyya", in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 24 April 2017

- ↑ Rogers, J.M., J. M. Rogers and J. Jomier, “al-Ḳāhira”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 24 April 2017

- ↑ Halm, Heinz. The Fatimids and their Traditions of Learning. London: The Institute of Ismaili Studies and I.B. Tauris. 1997.

- 1 2 3 Shorter Shi'ite Encyclopaedia, By: Hasan al-Amin, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 June 2010. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- ↑ "Cairo of the Mind". oldroads.org. 21 June 2007. Archived from the original on 12 December 2007.

- ↑ Wilson B. Bishai (1968). Islamic History of the Middle East: Backgrounds, Development, and Fall of the Arab Empire. Allyn and Bacon.

Nevertheless, the Seljuqs of Syria kept the Crusaders occupied for several years until the reign of the last Fatimid Caliph al-Adid (1160-1171) when, in the face of a Crusade threat, the caliph appointed a warrior of the Seljuq regime by the name of Shirkuh to be his chief minister.

- ↑ Brief History of Transfer of the Sacred Head of Hussain ibn Ali, From Damascus to Ashkelon to Qahera

- ↑ Brief History of Transfer of the Sacred Head of Husain ibn Ali, From Damascus to Ashkelon to Qahera By: Qazi Dr. Shaikh Abbas Borhany PhD (USA), NDI, Shahadat al A’alamiyyah (Najaf, Iraq), M.A., LLM (Shariah) Member, Ulama Council of Pakistan, Published in Daily News, Karachi, Pakistan on 03-1-2009.

- ↑ Cambridge History of Egypt, vol. 1, pg. 154.

- ↑ Cambridge History of Egypt, Vol. 1, pg. 155.

- ↑ Cambridge history of Egypt vol 1 page 155

- ↑ al Juyushi: A Vision of the Fatemiyeen. Graphico Printing Ltd. 2002. ISBN 978-0953927012.

- ↑ "Masjid al-Juyushi". Archnet.org. Archived from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ↑ Amin Maalouf (1984). The Crusades Through Arab Eyes. Al Saqi Books. pp. 160–170. ISBN 0-8052-0898-4.

- ↑ Enthoven, R. E. (1922). The Tribes and Castes of Bombay. 1. Asian Educational Services. p. 199. ISBN 81-206-0630-2.

- ↑ The Bohras, By: Asgharali Engineer, Vikas Pub. House, p.109,101

- ↑ , Mullahs on the Mainframe.., By Jonah Blank, p.139

- ↑ The Isma'ilis: Their History and Doctrines By Farhad Daftary; p.299

Further reading

- Brett, Michael (2001). The Rise of the Fatimids: The World of the Mediterranean and the Middle East in the Fourth Century of the Hijra, Tenth Century CE. The Medieval Mediterranean. 30. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 9004117415.

- Cortese, Delia, "Fatimids", in Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God (2 vols.), Edited by C. Fitzpatrick and A. Walker, Santa Barbara, ABC-CLIO, 2014, Vol I, pp. 187–191.

- Daftary, Farhad (1992). The Isma'ilis: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-42974-0.

- Daftary, Farhad (1999). "FATIMIDS". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IX, Fasc. 4. pp. 423–426.

- Halm, Heinz (1996). The Empire of the Mahdi: The Rise of the Fatimids. Handbook of Oriental Studies. 26. transl. by Michael Bonner. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 9004100563.

- Kennedy, Hugh N. (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second Edition). Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-58-240525-7.

- Lev, Yaacov (1987). "Army, Regime, and Society in Fatimid Egypt, 358–487/968–1094". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 19: 337–365. JSTOR 163658.

- Walker, Paul E. (2002). Exploring an Islamic Empire: Fatimid History and its Sources. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781860646928.

Notes

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fatimid Caliphate. |

- Fatimids entry in the Encyclopaedia of the Orient.

- The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London.

- The Shia Fatimid Dynasty in Egypt

— Imperial house — | ||

| Preceded by Abbasid dynasty |

Ruling house of Egypt 909–1171 |

Succeeded by Ayyubid dynasty as Abbasid autonomy |

| Titles in pretence | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Abbasid dynasty |

Caliphate dynasty 909–1171 |

Succeeded by Abbasid dynasty |