Charles Coughlin

| Monsignor Charles Edward Coughlin | |

|---|---|

Father Coughlin c. 1933 | |

| Church | Roman Catholic |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 1916 |

| Personal details | |

| Birth name | Charles Edward Coughlin |

| Born |

October 25, 1891 Hamilton, Ontario, Canada |

| Died |

October 27, 1979 (aged 88) Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, United States |

| Buried | Holy Sepulchre Cemetery, Southfield, Michigan |

| Parents | Thomas J. Coughlin and Amelia Mahoney |

Charles Edward Coughlin (/ˈkɒɡlɪn/ KOG-lin; October 25, 1891 – October 27, 1979), was a Canadian-American Roman Catholic priest based in the United States near Detroit. He was the founding priest at the National Shrine of the Little Flower church. Commonly known as Father Coughlin, he was one of the first political leaders to use radio to reach a mass audience: during the 1930s, an estimated 30 million listeners tuned to his weekly broadcasts. He was forced off the air in 1939 because of his pro-fascist and anti-semitic rhetoric.

Early in his radio career, Coughlin was a vocal supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal. Later he became a harsh critic of Roosevelt, accusing him of being too friendly to bankers. In 1934, he established a new political organization called the National Union for Social Justice. He issued a platform calling for monetary reforms, nationalization of major industries and railroads, and protection of the rights of labor. The membership ran into the millions, but it was not well-organized at the local level.[1]

After hinting at attacks on Jewish bankers, Coughlin began to use his radio program to broadcast antisemitic commentary. In the late 1930s, he supported some of the fascist policies of Adolf Hitler and of Benito Mussolini, and of Emperor Hirohito of Japan. The broadcasts have been described as "a variation of the Fascist agenda applied to American culture".[2] His chief topics were political and economic rather than religious, with his slogan being "Social Justice". Many American bishops as well as the Vatican wanted him silenced. After the outbreak of World War II in Europe in 1939, the Roosevelt administration finally forced the cancellation of his radio program and forbade distribution by mail of his newspaper, Social Justice.

Early life and work

Coughlin was born in Hamilton, Ontario, to Irish Catholic parents, Thomas J. Coughlin and Amelia née Mahoney.[3] After his basic education, he attended St. Michael's College in Toronto in 1911; it was run by the Congregation of St. Basil, a society of priests dedicated to education. After graduation, Coughlin entered the Basilian Fathers. He prepared for holy orders at St. Basil's Seminary, and was ordained to the priesthood in Toronto in 1916. He was sent to teach at Assumption College, also operated by the Basilians, in Windsor, Ontario.

In 1923, a change in the internal life of Coughlin's religious congregation resulted in his leaving the congregation. The Holy See required the Basilians to change the structure of the congregation from a society of common life, on the pattern of the Society of Priests of Saint Sulpice, to one requiring a more monastic way of life. They had to take the traditional three religious vows of chastity, poverty, and obedience. Coughlin could not accept this.

Leaving the congregation, Coughlin moved across the Detroit River to the United States, settling in the booming industrial city of Detroit, Michigan, where the auto industry was expanding rapidly. He was incardinated in 1923 by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Detroit in 1923. After being transferred several times to different parishes, in 1926 he was assigned to the newly founded Shrine of the Little Flower, at that time a congregation composed of some 25 Catholic families in what was the largely Protestant suburban community of Royal Oak, Michigan. His powerful preaching soon attracted more people to the parish congregation.[4]

Radio broadcaster

In 1926, Coughlin began his radio broadcasts on station WJR, in response to cross burnings by the Ku Klux Klan on the grounds of his church. The KKK was near the peak of its membership and power in Detroit. In this second manifestation of the KKK, which developed chapters in cities throughout the Midwest, its positions were strongly anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant. In response, Coughlin's weekly hour-long radio program denounced the KKK, appealing to his Irish Catholic audience.[5]

When WJR was acquired by Goodwill Stations in 1929, owner George A. Richards encouraged Coughlin to focus the program more on politics instead of religious topics.[6] Becoming increasingly vehement in tone, the broadcasts attacked the banking system and Jews. Coughlin's program was picked up by CBS in 1930 for national broadcast.[4][6]

Coughlin's vehement rhetoric in attacking his opponents has often been noted.[7][8] His angry, strident tone has been viewed in academic literature as being equivalent to later 20th-century talk radio.[6][9]

Political views

In January 1930, Coughlin began a series of attacks against socialism and Soviet Communism, which was strongly opposed by the Catholic Church. He also criticized capitalists in America whose greed had made communist ideology attractive to many Americans.[10] He warned, "Let not the workingman be able to say that he is driven into the ranks of socialism by the inordinate and grasping greed of the manufacturer."[11] Having gained a reputation as an outspoken anti-communist, in July 1930 Coughlin was given star billing as a witness before the House Un-American Activities Committee.[12]

In 1931, the CBS radio network dropped Coughlin's program when he refused to accept network demands that his scripts be reviewed prior to broadcast. He raised independent money to create his own national linkup, which soon reached millions of listeners on a 36-station hookup originating on flagship station WJR, for the Golden Hour of the Shrine of the Little Flower, as the program was called.[6]

Throughout the 1930s, Coughlin's views changed significantly. Eventually he was "openly antidemocratic," according to Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt, "calling for the abolition of political parties and questioning the value of elections."[13]

Support for FDR

Against the deepening crisis of the Great Depression, Coughlin strongly endorsed Franklin D. Roosevelt during the 1932 Presidential election. Similarly, he was an early supporter of Roosevelt's New Deal reforms and coined the phrase "Roosevelt or Ruin", which entered common usage during the early days of the first FDR administration. Another phrase he became known for was "The New Deal is Christ's Deal."[14] In January 1934, Coughlin testified before Congress in support of FDR's policies, saying, "If Congress fails to back up the President in his monetary program, I predict a revolution in this country which will make the French Revolution look silly!" He also said to the Congressional hearing, "God is directing President Roosevelt."[15]

Opposition to FDR

Coughlin's support for Roosevelt and his New Deal faded by 1934, when he founded the National Union for Social Justice (NUSJ), a nationalistic workers' rights organization. Its leaders grew impatient with what they thought to be the President's unconstitutional and pseudo-capitalistic monetary policies. Couglin preached more and more about the negative influence of "money changers" and "permitting a group of private citizens to create money" at the expense of the general welfare of the public.[16] He also spoke about the need for monetary reform based on "free silver". Coughlin claimed that the Great Depression in the United States was a "cash famine" and proposed monetary reforms, including the nationalization of the Federal Reserve System, as the solution.

Economic policies

Among the NUSJ's articles of faith were work and income guarantees, nationalizing necessary industry, wealth redistribution through taxation of the wealthy, federal protection of workers' unions, and decreasing property rights in favor of the government controlling the country's assets for public good.[17]

Illustrative of Coughlin's disdain for free market capitalism is his statement:

We maintain the principle that there can be no lasting prosperity if free competition exists in industry. Therefore, it is the business of government not only to legislate for a minimum annual wage and maximum working schedule to be observed by industry, but also so to curtail individualism that, if necessary, factories shall be licensed and their output shall be limited.[18]

Radio audience

By 1934, Coughlin was perhaps the most prominent Roman Catholic speaker on political and financial issues, with a radio audience that reached tens of millions of people every week. Alan Brinkley states that "by 1934, he was receiving more than 10,000 letters every day" and that "his clerical staff at times numbered more than a hundred".[19] He foreshadowed modern talk radio and televangelism.[20] In 1934, when Coughlin began criticizing the New Deal, Roosevelt sent Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr. and Frank Murphy, both prominent Irish Catholics, to try to tone him down.[21] Kennedy was reported to be a friend of Coughlin.[22][23] Coughlin periodically visited Roosevelt while accompanied by Kennedy.[24] In a August 16, 1936 Boston Post article, Coughlin referred to Kennedy as the "shining star among the dim 'knights' in the [Roosevelt] Administration."[25]

Increasingly opposed to Roosevelt, Coughlin began denouncing the President as a tool of Wall Street. The priest supported populist Huey Long as governor of Louisiana until Long was assassinated in 1935. He supported William Lemke's Union Party in 1936. Coughlin opposed the New Deal with increasing vehemence. His radio talks attacked Roosevelt, capitalists, and alleged the existence of Jewish conspirators. Another nationally known priest, Monsignor John A. Ryan, initially supported Coughlin, but opposed him after Coughlin turned on Roosevelt.[26] Joseph Kennedy, who strongly supported the New Deal, warned as early as 1933 that Coughlin was "becoming a very dangerous proposition" as an opponent of Roosevelt and "an out and out demagogue". Kennedy worked with Roosevelt, Bishop Francis Spellman, and Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli (the future Pope Pius XII) in a successful effort to get the Vatican to silence Coughlin in 1936.[27] In 1940–41, reversing his own views, Kennedy attacked the isolationism of Coughlin.[28][29][21]

In 1935, Coughlin proclaimed, "I have dedicated my life to fight against the heinous rottenness of modern capitalism because it robs the laborer of this world's goods. But blow for blow I shall strike against Communism, because it robs us of the next world's happiness."[30] He accused Roosevelt of "leaning toward international socialism on the Spanish question". Coughlin's NUSJ gained a strong following among nativists and opponents of the Federal Reserve, especially in the Midwest. As Michael Kazin notes, Coughlinites saw Wall Street and Communism as twin faces of a secular Satan. They believed that they were defending those people who were joined more by piety, economic frustration, and a common dread of powerful, modernizing enemies than through any class identity.[31]

One of Coughlin's campaign slogans was: "Less care for internationalism and more concern for national prosperity",[32] which appealed to the 1930s isolationists in the United States. Coughlin's organization especially appealed to Irish Catholics.

Anti-semitism

After the 1936 election, Coughlin expressed overt sympathy for the fascist governments of Hitler and Mussolini as an antidote to Communism.[33] According to him, Jewish bankers were behind the Russian Revolution[34] and backed the Jewish Bolshevism conspiracy theory.[35][36][37]

Coughlin promoted his controversial beliefs by means of his radio broadcasts and his weekly rotogravure magazine, Social Justice, which began publication in March 1936.[38] During the last half of 1938, Social Justice reprinted in weekly installments the fraudulent, antisemitic text The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.[39] The Protocols was a Russian forgery that purports to expose a Jewish conspiracy to seize control of the world.[40]

On various occasions, Coughlin denied that he was antisemitic.[41] In February 1939, when the American Nazi organization the German American Bund held a large rally in New York City,[42] Coughlin, in his weekly radio address, immediately distanced himself from the organization and said: "Nothing can be gained by linking ourselves with any organization which is engaged in agitating racial animosities or propagating racial hatreds. Organizations which stand upon such platforms are immoral and their policies are only negative."[43]

In August of that same year, in an interview with Edward Doherty of the weekly magazine Liberty, Coughlin said:

My purpose is to help eradicate from the world its mania for persecution, to help align all good men, Catholic and Protestant, Jew and Gentile, Christian and non-Christian, in a battle to stamp out the ferocity, the barbarism and the hate of this bloody era. I want the good Jews with me, and I'm called a Jew baiter, an anti-Semite.[44]

|

|

On November 20, 1938, two weeks after Kristallnacht (the Nazi attack on German Jews, their synagogues, and Jewish-owned businesses), Coughlin, referring to the millions of Christians killed by the Communists in Russia, said "Jewish persecution only followed after Christians first were persecuted."[46] After this speech, some radio stations, including those in New York and Chicago, began refusing to air Coughlin's speeches without subjecting his scripts to prior review and approval. In New York, his programs were cancelled by WINS and WMCA, and Coughlin broadcast only on the Newark part-time station WHBI.[47] On December 18, 1938 thousands of Coughlin's followers picketed the studios of station WMCA in New York City to protest the station's refusal to carry the priest's broadcasts. A number of protesters yelled anti-semitic statements, such as "Send Jews back where they came from in leaky boats!" and "Wait until Hitler comes over here!" The protests continued for several months.[48] Historian Donald Warren, using information from the FBI and German government archives, has documented that Coughlin received indirect funding from Nazi Germany during this period.[49]

After 1936, Coughlin began supporting an organization called the Christian Front, which claimed him as an inspiration. In January 1940, a New York City unit of the Christian Front was raided by the FBI for plotting to overthrow the government. Coughlin had never been a member.[50]

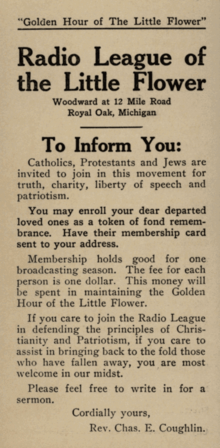

In March 1940, The Radio League of the Little Flower, creators of Social Justice magazine, self-published a book titled An Answer to Father Coughlin's Critics.[51][52] Written by "Father Coughlin's Friends," the book was an attempt to "deal with those matters which relate directly to the main charges registered against Father Coughlin ... to his being a pro-Nazi, anti-Semite, a falsifier of documents, etc." (preface).

Cancellation of radio show

At its peak in the early-to-mid 1930s, Coughlin's radio show was phenomenally popular. His office received up to 80,000 letters per week from listeners. Author Sheldon Marcus said that the size of Coughlin's radio audience "is impossible to determine, but estimates range up to 30 million each week."[53] He expressed an isolationist, and conspiratorial, viewpoint that resonated with many listeners.

Some members of the Catholic hierarchy may not have approved of Coughlin. The Vatican, the Apostolic Nunciature to the United States, and the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Cincinnati all wanted him silenced. They recognized that only Coughlin's superior, Bishop Michael Gallagher of Detroit, had the canonical authority to curb him, but Gallagher supported the "Radio Priest."[54] Owing to Gallagher's autonomy, and the prospect of the Coughlin problem leading to a schism, the Roman Catholic leadership took no action.[55]

Coughlin increasingly attacked the president's policies. The administration decided that, although the First Amendment protected free speech, it did not necessarily apply to broadcasting, because the radio spectrum was a "limited national resource," and regulated as a publicly owned commons. New regulations and restrictions were created specifically to force Coughlin off the air. For the first time, authorities required regular radio broadcasters to seek operating permits.

When Coughlin's permit was denied, he was temporarily silenced. Coughlin worked around the restriction by purchasing air-time, and playing his speeches via transcription. However, having to buy the weekly air-time on individual stations seriously reduced his reach, and strained his resources. Meanwhile, Bishop Gallagher died, and was replaced by a prelate less sympathetic to Coughlin. In 1939, the Institute for Propaganda Analysis used Coughlin's radio talks to illustrate propaganda methods in their book The Fine Art of Propaganda, which was intended to show propaganda's effects against democracy.[56]

After the outbreak of World War II in Europe in September 1939, Coughlin's opposition to the repeal of a neutrality-oriented arms embargo law resulted in additional and more successful efforts to force him off the air.[57] According to Marcus, in October 1939, one month after the invasion of Poland, "the Code Committee of the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) adopted new rules which placed rigid limitations on the sale of radio time to 'spokesmen of controversial public issues'."[58] Manuscripts were required to be submitted in advance. Radio stations were threatened with the loss of their licenses if they failed to comply. This ruling was clearly aimed at Coughlin, owing to his opposition to prospective American involvement in World War II. In the September 23, 1940, issue of Social Justice, Coughlin announced that he had been forced from the air "by those who control circumstances beyond my reach."[59]

Coughlin said that, although the government had assumed the right to regulate any on-air broadcasts, the First Amendment still guaranteed and protected freedom of the written press. He could still print his editorials without censorship in his own newspaper, Social Justice. After the [devastating Japanese [attack on Pearl Harbor]], and the U.S. declaration of war in December 1941, the anti-interventionist movements (such as the America First Committee) rapidly lost support. Isolationists such as Coughlin acquired the reputation of sympathy with the enemy. The Roosevelt Administration stepped in again. On April 14, 1942, U.S. Attorney General Francis Biddle wrote a letter to the Postmaster General, Frank Walker, and suggested revoking the second-class mailing privilege of Social Justice, which would make it impossible for Coughlin to deliver the papers to his readers.[60] Walker scheduled a hearing for April 29, which was postponed until May 4.[61]

Meanwhile, Biddle was also exploring the possibility of bringing an indictment against Coughlin for sedition as a possible "last resort".[62] Hoping to avoid such a potentially sensational and divisive sedition trial, Biddle was arranged to end the publication of Social Justice itself. First Biddle had a meeting with banker Leo Crowley, another Roosevelt political appointee and friend of Bishop Edward Aloysius Mooney of Detroit, Bishop Gallagher's successor. Crowley relayed Biddle's message to Mooney that the government was willing to "deal with Coughlin in a restrained manner if he [Mooney] would order Coughlin to cease his public activities."[63] Consequently, on May 1, Bishop Mooney ordered Coughlin to stop his political activities and to confine himself to his duties as a parish priest, warning of potentially removing his priestly faculties if he refused. Coughlin complied and was allowed to remain the pastor of the Shrine of the Little Flower. The pending hearing before the Postmaster, which had been scheduled to take place four days later, was cancelled as it was no longer necessary.

Although forced to end his public career, Coughlin served as parish pastor until retiring in 1966. He died in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan in 1979 at the age of 88. He was buried in Holy Sepulchre Cemetery in Southfield, Michigan.

References in popular culture

- Coughlin was mentioned in a verse of Woody Guthrie's pro-interventionist song "Lindbergh": "Yonder comes Father Coughlin, wearin' the silver chain, Cash on the stomach and Hitler on the brain."

- Dr. Seuss (Theodor Seuss Geisel) attacked Coughlin in a series of 1942 political cartoons.[64]

- Sinclair Lewis's 1935 novel about a fascist coup in the United States, It Can't Happen Here, features a "Bishop Prang", an extremely successful pro-fascist radio host who is said to be "to the pioneer Father Coughlin ... as the Ford V-8 [was] to the Model A".

- The producers of the HBO television series Carnivàle have said that Coughlin was a historical reference for the character of Brother Justin Crowe.[65]

- In the alternate history work The Plot Against America (2004), author Philip Roth uses Coughlin as the villain who helps Charles Lindbergh form a pro-fascist American government.

- Sax Rohmer's 1936 novel President Fu Manchu features a character based on Coughlin named Dom Patrick Donegal, a Catholic priest and radio host who is the only person who knows that a criminal mastermind is manipulating a U.S. presidential race.

- Cole Porter referenced and rhymed "Coughlin" in his 1935 song "A Picture of Me Without You" (in the fourth refrain): "Picture City Hall without boondogglin', picture Sunday tea minus Father Coughlin".

- Coughlin's influence on American antisemitic organizations in the 1930s and 1940s is referenced in Arthur Miller's 1945 novel Focus.

- Harry Turtledove's Joe Steele is an alternate history with Coughlin in a supporting role.

- Paradox Interactive's Hearts of Iron IV World War II grand strategy game casts Coughlin as the USA's fascist demagogue. In the popular alternate history mod "Kaiserreich", Coughlin plays a larger role, and his rhetoric can cause a diplomatic tensions between the US and the Papal State.

See also

- John Francis Cronin

- Jozef Tiso

- Frank J. Hogan, ABA president who rebutted Coughlin on the air

Footnotes

- ↑ Kennedy 1999, p. 232.

- ↑ DiStasi 2001, p. 163.

- ↑ "Father Charles Coughlin". FamousWhy. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- 1 2 "Charles Coughlin biography". Browse Biography. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ↑ Shannon 1989, p. 298.

- 1 2 3 4 Schneider, John (September 1, 2018). "The Rabble-Rousers of Early Radio Broadcasting". Radio World. Vol. 42 no. 22. Future US. pp. 16–18.

- ↑ Michael Casey and Aimee Rowe. "'Driving Out the Money Changers': Radio Priest Charles E. Coughlin's Rhetorical Vision." Journal of Communication & Religion 19.1 (1996).

- ↑ Ronald H. Carpenter, "Father Charles E. Coughlin, Style in Discourse and Opinion Leadership," in Thomas W. Benson, ed., American Rhetoric in the New Deal Era, 1932-1945 (Michigan State University Press, 2006) pp 315-67.

- ↑ Jack Kay, George W. Ziegelmueller, and Kevin M. Minch. "From Coughlin to contemporary talk radio: Fallacies & propaganda in American populist radio," Journal of Radio Studies 5.1 (1998): 9-21.

- ↑ Marcus 1972, pp. 31-32.

- ↑ Brinkley 1982, p. 95.

- ↑ Marcus 1972, p. 2.

- ↑ Levitsky, Steven; Ziblatt, Daniel (16 January 2018). How Democracies Die (First edition, ebook ed.). Crown Publishing. p. 31. ISBN 9781524762957.

- ↑ Rollins & O'Connor 2005, p. 160.

- ↑ "'Roosevelt or Ruin', Asserts Radio Priest at Hearing". The Washington Post. January 17, 1934. pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Carpenter 1998, p. 173.

- ↑ "Principles of the National Union for Social Justice", quoted in Brinkley 1982, pp. 287–288.

- ↑ Beard & Smith 1936, p. 54.

- ↑ Brinkley 1982, p. 119.

- ↑ Sayer 1987, pp. 17-30.

- 1 2 Brinkley 1982, p. 127.

- ↑ [https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/697

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=PLP5U-M8dhoC&pg=PA136&lpg=PA136&dq=charles+coughlin+joe+kennedy&source=bl&ots=7wu_6lZ5sH&sig=kHz05hS7ecLs3RVnpff4-wplnko&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiN0-XgiLDcAhWCrFQKHaBFC544ChDoAQhHMAU#v=onepage&q=charles%20coughlin%20joe%20kennedy&f=false], History News Network

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=0Sfkdhf3JwwC&pg=PA148&lpg=PA148&dq=kennedy+coughlin&source=bl&ots=NrCp_QbvLa&sig=Hig323fsYLPdvA1MqpO-TqrwXGg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiwirrIirDcAhWJjVQKHXjyBaw4ChDoAQg6MAQ#v=onepage&q=kennedy%20coughlin&f=false

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=17F5wKC_rtgC&pg=PT498&lpg=PT498&dq=frank+murphy+joe+kennedy+spellman+coughlin&source=bl&ots=vFRJoBEN0H&sig=xEC9OoIvZEsPuxh45UItED3bVR8&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjNleuEm_zdAhWOxIMKHTdtAhgQ6AEwEXoECAcQAQ#v=onepage&q=frank%20murphy%20joe%20kennedy%20spellman%20coughlin&f=false

- ↑ Turrini 2002, pp. 7, 8, 19.

- ↑ Maier 2003, pp. 103-107.

- ↑ Smith 2002, pp. 122, 171, 379, 502.

- ↑ Kazin 1995, pp. 109, 123.

- ↑ Kazin 1995, pp. 109.

- ↑ Kazin 1995, pp. 112.

- ↑ Brinkley 1982.

- ↑ Marcus 1972, pp. 189–190.

- ↑ Marcus 1972, pp. 188–189.

- ↑ Tull 1965, p. 197.

- ↑ Marcus 1972, pp. 256.

- ↑ Schrag 2010.

- ↑ Marcus 1972, pp. 181–182.

- ↑ Marcus 1972, p. 188.

- ↑ Tull 1965, p. 193.

- ↑ Tull 1965, pp. 195, 211–212, 224–225.

- ↑ Bredemus 2011.

- ↑ Coughlin 1939.

- ↑ Tull 1965, pp. 211-212.

- ↑ "Radio Priest: Charles Coughlin". C-SPAN. September 8, 1996. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ↑ Dollinger 2000, p. 66.

- ↑ , Pp. 15.

- ↑ Warren 1996, pp. 165–169.

- ↑ Warren 1996, pp. 235–244.

- ↑ "Coughlin Supports Christian Front". New York Times. January 22, 1940. Retrieved February 18, 2010.

- ↑ Father Charles E. Coughlin: Surrogate Spokesman for the Disaffected, Ronald H. Carpenter, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1998

- ↑ An Answer to Father Coughlin's Critics, Radio League of the Little Flower, 1940

- ↑ Marcus, Sheldon (1973). Father Coughlin; the tumultuous life of the priest of the Little Flower. Boston: Little, Brown. p. 4. ISBN 0316545961.

- ↑ Boyea, Earl (1995). "The Reverend Charles Coughlin and the Church: the Gallagher Years, 1930-1937". Catholic Historical Review. 81 (2): 211–225.

- ↑ Boyea 1995.

- ↑ Alfred McClung Lee & Elizabeth Briant Lee (1939), The Fine Art of Propaganda: A Study of Father Coughlin’s Speeches, Harcourt, Brace and Company

- ↑ Marcus 1972, pp. 175-176.

- ↑ Marcus 1972, p. 176.

- ↑ Marcus 1972, pp. 176-177.

- ↑ Dinnerstein, Leonard (1995). Antisemitism in America. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531354-3.

- ↑ Marcus 1972, pp. 209-214, 217.

- ↑ Tull 1965, p. 235.

- ↑ Marcus 1972, p. 216.

- ↑ "Dr. Seuss Went to War". Libraries.ucsd.edu. February 9, 1942. Retrieved 2017-05-24.

- ↑ "Carnivale press conference". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on April 29, 2009. Retrieved December 26, 2013.

References

- Beard, Charles A.; Smith, George H.E., eds. (1936). Current Problems of Public Policy: A Collection of Materials. New York: The Macmillan Company. p. 54.

- Boyea, Earl (1995). "The Reverend Charles Coughlin and the Church: the Gallagher Years, 1930-1937". Catholic Historical Review. 81 (2): 211–225.

- Bredemus, Jim (2011). "American Bund - The Failure of American Nazism: The German-American Bund's Attempt to Create an American "Fifth Column"". TRACES. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- Brinkley, Alan (1982). Voices of Protest: Huey Long, Father Coughlin, and the Great Depression. New York: Knopf Publishing Group. ISBN 0-394-52241-9.

- Carpenter, Ronald H. (1998). Father Charles E. Coughlin. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 173.

- Coughlin, Charles (Feb 27, 1939). "Column". NY Times.

- Dollinger, Marc (2000). Quest for Inclusion. Princeton University Press.

- DiStasi, Lawrence (May 1, 2001). Una storia segreta: The Secret History of Italian American Evacuation and Interment During World II. (Heyday Books). p. 163.

- Kazin, Michael (1995). The Populist Persuasion: An American History. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-03793-3.

- Kennedy, David M. (1999). Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945. Oxford University Press. p. 232.

- Lawrence, John Shelton; Jewett, Robert (2002). The Myth of the American Superhero. Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 132.

- Marcus, Sheldon (1972). Father Coughlin: The Tumultuous Life Of The Priest Of The Little Flower. Boston: Little, Brown and Co. ISBN 0-316-54596-1.

- Maier, Thomas (2003). The Kennedys: America's Emerald Kings. pp. 103–107.

- Rollins, Peter C.; O'Connor, John E. (2005). Hollywood's White House: The American Presidency in Film and History. University Press of Kentucky. p. 160.

- Sayer, J. (1987). "Father Charles Coughlin: Ideologue and Demagogue of the Depression". Journal of the Northwest Communication Association. 15 (1): 17–30.

- Schrag, Peter (2010). Not Fit for Our Society: Nativism and Immigration. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520259782.

- Severin, Werner Joseph; Tankard, James W. (2001) [1997]. Communication Theories (5th revised ed.). Longman. ISBN 0-8013-3335-0.

- Shannon, William V. (1989) [1963]. The American Irish: a political and social portrait. p. 298. ISBN 978-0-87023-689-1. OCLC 19670135.

- Smith, Amanda (2002). Hostage to Fortune. pp. 122, 171, 379, 502.

- Tull, Charles J. (1965). Father Coughlin and the New Deal. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-0043-7.

- Turrini, Joseph M. (March 2002). "Catholic Social Reform and the New Deal" (PDF). Annotation. National Historical publications and Records Commission. 30 (1): 7, 8, 19. Retrieved February 2, 2013.

- Warren, Donald (1996). Radio Priest: Charles Coughlin The Father of Hate Radio. New York: The Free Press. ISBN 0-684-82403-5.

- Woolner, David B.; Kurial, Richard G. (2003). FDR, the Vatican, and the Roman Catholic Church in America, 1933-1945. p. 275.

- Abzug, Robert E. American Views of the Holocaust, 1933-1945. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1999.

- Athans, Mary Christine. "A New Perspective on Father Charles E. Coughlin". Church History 56:2 (June 1987), pp. 224–235.

- Athans, Mary Christine. The Coughlin-Fahey Connection: Father Charles E. Coughlin, Father Denis Fahey, C.S. Sp., and Religious Anti-Semitism in the United States, 1938-1954. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 1991. ISBN 0-8204-1534-0

- Carpenter, Ronald H. "Father Charles E. Coughlin: Delivery, Style in Discourse, and Opinion Leadership", in American Rhetoric in the New Deal Era, 1932-1945. E. Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 2006, pp. 315–368. ISBN 0-87013-767-0

- General Jewish Council. Father Coughlin: His "Facts" and Arguments. New York: General Jewish Council, 1939.

- Hangen, Tona J. Redeeming the Dial: Radio, Religion and Popular Culture in America. Raleigh, NC: University of North Carolina Press. 2002. ISBN 0-8078-2752-5

- O'Connor, John J. "Review/Television: Father Coughlin, 'The Radio Priest'". The New York Times. December 13, 1988.

- Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr. The Age of Roosevelt: The Politics of Upheaval, 1935-1936. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003. (Originally published in 1960.) ISBN 0-618-34087-4

- Sherrill, Robert. "American Demagogues". The New York Times. July 13, 1982.

- Smith, Geoffrey S. To Save A Nation: American Counter-Subversives, the New Deal, and the Coming of World War II. New York: Basic Books, 1973. ISBN 0-465-08625-X

- Spivak, John L. Shrine of the Silver Dollar. New York: Modern Age Books, 1940.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Coughlin. |

- Works by or about Charles Coughlin at Internet Archive

- "Father Charles E. Coughlin; Social Security History". ssa.gov. Social Security Administration. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- Father Coughlin & The Search For "Social Justice" Text

- Brief information on Coughlin, including an audio excerpt

- "Charles Edward Coughlin". Find a Grave. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- Video of Father Coughlin attacking Roosevelt

- History Channel Audio File- Father Coughlin denouncing the New Deal

- American Jewish Committees extensive archive on Coughlin; includes contemporary pamphlets and correspondence

- Father Charles Coughlin FBI Files at the Walter P. Reuther Library

- Am I An Anti-Semite? by Charles Coughlin at archive.org

- Father Charles Coughlin radio broadcasts at archive.org

- Newspaper clippings about Charles Coughlin in the 20th Century Press Archives of the German National Library of Economics (ZBW)