Université de Montréal

Coordinates: 45°30′17″N 73°36′46″W / 45.50472°N 73.61278°W

| |

| Latin: Universitas Montis Regii | |

Former name | Université Laval à Montréal |

|---|---|

| Motto | Fide splendet et scientia (Latin) |

Motto in English | It shines by faith and knowledge |

| Type | Public |

| Established | 1878 |

| Endowment | $339.730 million[1] |

| Budget | $1.05 billion[2] |

| Rector | Guy Breton |

Academic staff | 7,329[3] |

Administrative staff | 4,427[3] |

| Students | 67,542 total (46,725 without its affiliated schools)[4] |

| Undergraduates | 34,335[5] |

| Postgraduates | 11,925[5] |

| Location | Montreal, Quebec, Canada |

| Campus | Urban, park, 60 ha (150 acres) |

| Language | French |

| Colours | Royal blue, white and black |

| Athletics | 15 varsity teams |

| Nickname | Carabins |

| Affiliations | AUCC, IAU, AUF, AUFC, ACU, U Sports, QSSF, IFPU, U15, CBIE, CUP. |

| Mascot | Carabin |

| Website |

www |

| |

The Université de Montréal[6] (UdeM; French pronunciation: [ynivɛʁsite də mɔ̃ʁeal]) is a French-language public research university in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. The university's main campus is located on the northern slope of Mount Royal in the Outremont and Côte-des-Neiges boroughs. The institution comprises thirteen faculties, more than sixty departments and two[7] affiliated schools: the Polytechnique Montréal (School of Engineering; formerly the École Polytechnique de Montréal) and HEC Montréal (School of Business). It offers more than 650 undergraduate programmes and graduate programmes, including 71 doctoral programmes.

The university was founded as a satellite campus of the Université Laval in 1878. It became a independent institution after it was issued a papal charter in 1919, and a provincial charter in 1920. Université de Montréal moved from Montreal's Quartier Latin to its present location at Mount Royal in 1942. It was made a secular institution with the passing of another provincial charter in 1967.

The school is co-educational, and has over 34,335 undergraduate and over 11,925 post-graduate students (excluding affiliated schools). Alumni and former students reside across Canada and around the world, with notable alumni serving as government officials, academics, and business leaders. It was ranked 101–150 in the 2018 Academic Ranking of World Universities,[8] 149th in the 2019 QS World University Rankings.[9] 90th in the 2019 Times Higher Education World University Rankings,[10] and 129th in the 2018 U.S. News & World Report global university ranking.[11] Its athletic teams are known as the Carabins, and are members of U Sports.

History

The Université de Montréal was founded in 1878 as a new branch of Université Laval in Quebec City. It was then known as the Université de Laval à Montréal.[12] The move initially went against the wishes of Montréal's prelate, who advocated an independent university in his city.[13] Certain parts of the institution's educational facilities, such as those of the Séminaire de Québec and the Faculty of Medicine, founded as the Montreal School of Medicine and Surgery, had already been established in Montréal in 1876 and 1843, respectively.[14]

The Vatican granted the university some administrative autonomy in 1889, thus allowing it to choose its own professors and license its own diplomas. However, it was not until 8 May 1919 that a papal charter from Pope Benedict XV granted full autonomy to the university.[15] It thus became an independent Catholic university and adopted Université de Montréal as its name.[16] Université de Montréal was granted its first provincial charter on 14 February 1920.[15]

At the time of its creation, less than a hundred students were admitted to the university's three faculties, which at that time were located in Old Montreal. These were the Faculty of Theology (located at the Grand séminaire de Montréal), the Faculty of Law (hosted by the Society of Saint-Sulpice), and the Faculty of Medicine (at the Château Ramezay).[17][18]

Graduate training based on German-inspired American models of specialized coursework and completion of a research thesis was introduced and adopted.[14] Most of Québec's secondary education establishments employed classic course methods of varying quality. This forced the university to open a preparatory school in 1887 to harmonize the education level of its students. Named the "Faculty of Arts", this school would remain in use until 1972 and was the predecessor of Québec's current CEGEP system.[19]

Two distinct schools eventually became affiliated to the university. The first was the École Polytechnique, a school of engineering, which was founded in 1873 and became affiliated in 1887. The second was the École des Hautes Études Commerciales, or HEC (a business school), which was founded in 1907 and became part of the university in 1915.[17] In 1907, Université de Montréal opened the first francophone school of architecture in Canada at the École Polytechnique.[20]

Between 1920 and 1925, seven new faculties were added: Philosophy, Literature, Sciences, Veterinary Medicine, Dental Surgery, Pharmacy, and Social Sciences.[21] Notably, the Faculty of Social Sciences was founded in 1920 by Édouard Montpetit, the first laic to lead a faculty.[22] He thereafter was named secretary-general, a role he fulfilled until 1950.

From 1876 to 1895, most classes took place in the Grand séminaire de Montréal. From 1895 to 1942, the school was housed in a building at the intersection of Saint-Denis and Sainte-Catherine streets in Montreal's eastern downtown Quartier Latin. Unlike English-language universities in Montréal, such as McGill University, Université de Montréal suffered a lack of funding for two major reasons: the relative poverty of the French Canadian population and the complications ensuing from its being managed remotely, from Quebec City. The downtown campus was hit by three different fires between 1919 and 1921, further complicating the university's already precarious finances and forcing it to spend much of its resources on repairing its own infrastructure.[21]

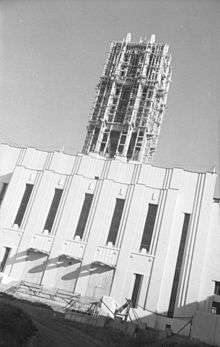

By 1930, enough funds had been accumulated to start the construction of a new campus on the northwest slope of Mount Royal, adopting new plans designed by Ernest Cormier. However, the financial crisis of the 1930s virtually suspended all ongoing construction.[23] Many speculated that the university would have to sell off its unfinished building projects in order to ensure its own survival. Not until 1939 did the provincial government directly intervene by injecting public funds.[24]

The campus's construction subsequently resumed and the mountain campus was officially inaugurated on 3 June 1943.[25] The Cote-des-Neiges site includes property expropriated from a residential development along Decelles Avenue, known as Northmount Heights.[26] The university's former downtown facilities would later serve Montreal's second francophone university, the Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM).

In 1943, the university assisted the Western Allies by providing laboratory accommodations on its campus. Scientists there worked to develop a nuclear reactor, notably by conducting various heavy water experiments. The research was part of the larger Manhattan Project, which aimed to develop the first atomic bomb. Scientists working on the school's campus eventually produced the first atomic battery to work outside of the United States. One of the participating Québec scientists, Pierre Demers, also discovered a series of radioactive elements issued from Neptunium.[27]

Université de Montréal was issued its second provincial charter in 1950.[15] A new government policy of higher education during the 1960s (following the Quiet Revolution) came in response to popular pressure and the belief that higher education was key to social justice and economic productivity.[14] The policy led to the school's ' third provincial charter, which was passed in 1967. It defined the Université de Montréal as a public institution, dedicated to higher learning and research, with students and teachers having the right to participate in the school's administration.[15]

In 1965, the appointment of the university's first secular rector, Roger Gaudry, paved the way for modernization. The school established its first adult-education degree program offered by a French Canadian university in 1968. That year the Lionel-Groulx and 3200 Jean-Brillant buildings were inaugurated, the former being named after Quebec nationalist Lionel Groulx. The following year, the Louis Collin parking garage - which won a Governor General's medal for its architecture in 1970 - was erected.

An important event that marked the university's history was the École Polytechnique massacre. On 6 December 1989, a gunman armed with a rifle entered the École Polytechnique building, killing 14 people, all of whom were women, before taking his own life.

Since 2002, the university has embarked on its largest construction project since the late 1960s, with the construction of five new buildings planned for advanced research in pharmacology, engineering, aerospace, cancer studies and biotechnology.[17]

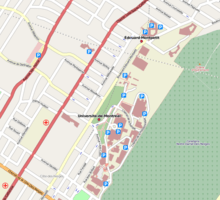

Campus

The university's main campus is located on the northern slope of Mount Royal in the Outremont and Côte-des-Neiges boroughs. Its landmark Pavilion Roger-Gaudry - known until 2003 as Pavillon principal [28] - and named for former rector Roger Gaudry - can be seen from around the campus and is known for its imposing tower. It is built mainly in the Art Deco style with some elements of International style and was designed by noted architect Ernest Cormier. On 14 September 1954, a Roll of Honour plaque on the wall at the right of the stairs to the Court of Honour in Roger-Gaudry Pavillon was dedicated to alumni of the school who died in while in the Canadian military during the Second World War. [29] On November 1963, a memorial plaque was dedicated to the memory of those members of the Université de Montréal who served in the Armed Forces during the First and Second World Wars and Korea.[30] The Mont-Royal campus is served by the Côte-des-Neiges, Université-de-Montréal, and Édouard-Montpetit metro stations.

Apart from its main Mont-Royal campus, the university also maintains five regional facilities in Terrebonne, Laval, Longueuil, Saint-Hyacinthe and Mauricie.[31] The campus in Laval, just north of Montréal, was opened in 2006. It is Laval's first university campus, and is located in the area near the Montmorency metro station. In October 2009, the university announced an expansion of its Laval satellite campus with the commissioning of the six-storey Cité du Savoir complex.[32] In order to solve the problem of lack of space on its main campus, the university is also planning to open a new campus in Outremont.[33]

The Centre hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal (CHUM) and the Centre hospitalier universitaire Sainte-Justine are the two teaching hospital networks of the Université de Montréal's Faculty of Medicine, although the latter is also affiliated with other medical institutions such as the Institut universitaire de gériatrie de Montréal, Montreal Heart Institute, Hôpital Sacré-Coeur and Hôpital Maisonneuve-Rosemont. A plaque dedicated to the personnel of the "Hôpital Général Canadien No. 6 (Université Laval de Montréal)" from 1916 to 1920 was donated by Mr. Louis de Gonzague Beaubien in 1939.[34]

The J.-Armand-Bombardier Incubator[35] is among buildings jointly erected by the Université de Montréal and Polytechnique Montréal. The incubator is part on the main Campus of Université de Montréal and was built in the fall of 2004 with the aim of helping R&D-intensive startup companies by providing complete infrastructures at advantageous conditions.

The environment helps promote collaboration between industries and academics while encouraging Quebec entrepreneurship. Since its creation the Incubator has hosted more than fifteen companies, mainly in the biomedical field (Cuttle Pharmaceuticals, Angiotech, Siegfried, Haemacure) in the field of polymer / surface treatment (Solaris Chem, Cerestech, Nanomextrix, Novaplasma) in optics / photonics (Photon etc., Castor Optics, Thorlabs, Genia Photonics) and IT security (ESET, Urqui).

Academics

The University of Montreal is a publicly funded research university, and a member of the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada.[36] Undergraduate students make the majority of the university community, accounting for 74 percent of the university student body, followed by master students at 19 percent, and doctoral students at 7 percent.[3] The full-time undergraduate programs comprise the majority of the school's enrolment, made up of 42,684 undergraduate students. From the 1 June 2010 to the 31 May 2011, the university conferred 7,012 bachelor's degrees, 461 doctoral degrees, and 3,893 master's degrees.[3]

Depending on a student's citizenship, they may be eligible for financial assistance from the Student Financial Assistance program, administered by the provincial Ministry of Education, Recreation and Sports, and/or the Canada Student Loans and Grants through the federal and provincial governments. The university's Office of Financial Aid acts as intermediaries between the students and the Quebec government for all matters relating to financial assistance programs.[37] The financial aid provided may come in the form of loans, grants, bursaries, scholarships fellowships and work programs.

Reputation

| University rankings | |

|---|---|

| Global rankings | |

| ARWU World[8][38] | 101-150 |

| QS World[9] | 149 |

| Times World[10] | 90 |

| Times Employability[39] | 44 |

| U.S News & World Report Global[11] | 129 |

| Canadian rankings | |

| ARWU National[8] | 5–6 |

| QS National[9] | 6 |

| Times National[10] | 5 |

| U.S News & World Report National[11] | 5 |

| Maclean's Medical/Doctoral[40] | 10 |

| Maclean's Reputation[41] | 10 |

The 2019 Times Higher Education World University Rankings placed the university 90th in the world, and fifth in Canada.[10] The 2019 QS World University Rankings ranked the university 149th in the world, and sixth in Canada.[9] In the 2018 Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) rankings, the university was ranked 101-150th in the world.[8] In terms of national rankings, Maclean's has ranked the university 10th in its 2019 Medical Doctoral university rankings.[40] The university was ranked in spite of having opted out - along several other universities in Canada - from participating in Maclean's graduate survey since 2006 amid a sense the ranking's methodology was unfair toward certain universities.[42]

The university was ranked 76-100th in the 2012 ARWU rankings within the field of social sciences, and 5-8th in the country.[43] The 2012-2013 Times Higher Education rankings for clinical, pre-clinical, and health universities, the university's health science programs ranked 47th in the world and fourth in Canada.[44] The Université de Montréal Faculty of Law was ranked second, out of the six civil law schools in Canada in Maclean's 2011 law school rankings.[45] The university was also ranked 56th in the world for computer science in the 2018 Times Higher Education rankings.[46]

HEC Montréal, a business school affiliated with the university, has also received significant recognition. The business school was ranked 12th in the 2011 Forbes ranking of the best international one-year MBA programs, placing higher than any other Canadian business school.[47] The 2011 Financial Times ranking for master's in management programs placed HEC Montréal 39th in the world and first in the country.[48] In CNN Expansion's 2011 ranking of the world's best MBA program, HEC Montréal was ranked 62nd in the world, and second nationally.[49] In The Economist's 2011 ranking of the best MBA program in North America, HEC Montréal was 56th on the continent, and fifth nationally.[50] The 2010 Bloomberg Businessweek biannual business school rankings ranked HEC Montréal as the 15th best business school outside the United States, and the sixth best business school in Canada.[51] The QS ranking of North American MBA programs placed HEC Montréal 30th in North America, and 7th in Canada.[52] In an employability survey published by the New York Times in October 2011, when CEOs and chairmans were asked to select the top universities which they recruited from, HEC Montréal placed 46th in the world, and second in Canada.[53]

Research

In Research Infosource's 2013 ranking of Canada's 50 top research universities, the university was ranked third, with a sponsored-research income of $526,213,000, the third largest in the country. The university had an average of $280,000 per faculty member, making it the fifth most research-intensive full-service university.[54] In terms of research performance, High Impact Universities 2010 ranked the university 108th out of 500 universities, and sixth in the country.[55] In the field of medicine, dentistry, pharmacology, and health sciences, the 2010 High Impact Universities ranking placed Université de Montréal 68th in the world, and fifth nationally.[56] In the field of life, agricultural and biological sciences, the 2010 High Impact Universities ranking placed the university 99th in the world, and fourth in Canada.[57]

The Higher Education Evaluation and Accreditation Council of Taiwan (HEEACT), an organization that also evaluates universities based on their scientific paper's performances, ranked the university 101st in the world, and sixth in Canada.[58] In HEEACT's 2011 rankings, which focused on life sciences, the university was ranked 81st in the world, and fourth in Canada.[59] In HEEACT's rankings focusing on clinical medicines, the university placed 81st in the world, and sixth in the country.[60] The HEEACT rankings focusing on social sciences placed the university 83rd in the world and seventh in Canada.[61] In the Higher Education Strategy Associates 2012 ranking of Canadian universities based on research strength, Université de Montréal was placed second nationally in the field of science and engineering and sixth nationally in the field of social sciences and humanities.[62]

Student life

The school's two main student unions are the Fédération des associations étudiantes du campus de l'Université de Montréal (FAÉCUM), which represents all full-time undergraduate and graduate students, and the Association Étudiante de la Maîtrise et du Doctorat de HEC Montréal (AEMD), which defends the interests of those enrolled in HEC Montréal.[63][64] FAÉCUM traces its lineage back to 1989, when the Fédération étudiante universitaire du Québec (FEUQ) was founded, and is currently the largest student organization in Québec.[65] Accredited organizations and clubs on campus cover a wide range of interests ranging from academics to cultural, religion and social issues. FAÉCUM is currently associated with 82 student organizations and clubs.[66] Four fraternities and sororities are recognized by the university's student union, Sigma Thêta Pi, Nu Delta Mu, Zeta Lambda Zeta, Eta Psi Delta.[67]

Media

The university's student population operates a number of news media outlets. The Quartier Libre is the school's main student newspaper.[68] CISM-FM is an independently-owned radio station. It is owned by the students of the Université de Montréal and operated by the student union.[69] The radio station dates back to 1970, and it received a permit from the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) on 10 July 1990 to transmit on an FM band. On 14 March 1991, CISM's broadcasting antenna was boosted to 10 000 watts. With a broadcasting radius of 70 km, CISM is now the world's largest French-language university radio station.[70] The CFTU-DT television station also receives technical and administrative support from the student body.[71]

Sports

Université de Montréal's sports teams are known as the Carabins. The Carabins participate in the U Sports' Réseau du sport étudiant du Québec (RSEQ) conference for most varsity sports. Varsity teams include badminton, Canadian football, cheerleading, golf, hockey, swimming, alpine skiing, soccer, tennis, track and field, cross-country, and volleyball.[72] The athletics program at the university dates back to 1922.[73] The university's athletic facilities is open to both its varsity teams and students. The largest sports facility is the Centre d'éducation physique et des sports de l'Université de Montréal (CEPSUM), which is also home to all of the Carabin's varsity teams.[74] The CEPSUM's building was built in 1976 in preparation for the 1976 Summer Olympics held in Montréal. The outdoor stadium of the CEPSUM, which hosts the university's football team, can seat around 5,100 people.[74]

Notable alumni and faculty

.jpg)

- Pierre Karl Péladeau, former president and CEO of Quebecor.

The university has an extensive alumni network, with more than 300,000 members of the university's alumni network.[75] Throughout the university's history, faculty, alumni, and former students have played prominent roles in a number of fields. Several prominent business leaders have graduated from the university. Graduates include Philippe de Gaspé Beaubien, founder and CEO of Telemedia,[76] Louis R. Chênevert, chairman and CEO of the United Technologies Corporation,[77] and Pierre Karl Péladeau, former president and CEO of Quebecor.[78]

A number of students have also gained prominence for their research and work in a number of scientific fields. Roger Guillemin, a graduate of the university, would later be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work with neurohormones.[79] Alumnus Ishfaq Ahmad, would also gain prominence for his work with Pakistan's nuclear weapon's program.[80] Jocelyn Faubert, known for his work in the fields of visual perception, is currently a faculty member of the university.[81] Gilles Brassard, best known for his fundamental work in quantum cryptography, quantum teleportation, quantum entanglement distillation, quantum pseudo-telepathy, and the classical simulation of quantum entanglement.[82] Ian Goodfellow is a thought leader in the field of artificial intelligence.

Many former students have gained local and national prominence for serving in government, including Former Supreme Court of Canada Judge and UN Human Rights Commissioner Louise Arbour. Michaëlle Jean served as Governor General of Canada,[83] Ahmed Benbitour, who served as the Prime Minister of Algeria,[84] and Pierre Trudeau who served as the Prime Minister of Canada.[85] Eleven Premiers of Quebec have also graduated from Université de Montréal, including Jean-Jacques Bertrand,[86] Robert Bourassa,[87] Maurice Duplessis,[88] Lomer Gouin,[89] Daniel Johnson, Jr.,[90] Daniel Johnson Sr.,[86] Pierre-Marc Johnson,[91] Bernard Landry,[92] Jacques Parizeau,[93] Paul Sauvé [94] and Philippe Couillard.

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ "État des résultats et de l'évolution des soldes de fonds" (PDF). États financiers de l'Université de Montréal (in French). Université de Montreal. 25 September 2017. p. 3. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ↑ "État des résultats et de l'évolution des soldes de fonds" (PDF). États financiers de l'Université de Montréal (in French). Université de Montreal. 30 September 2014. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Université de Montréal official statistics". Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ http://recteur.umontreal.ca/fileadmin/recteur/pdf/documents-institutionnels/UdeM-at-a-Glance2016_ENG.pdf

- 1 2 "Statistiques d'inscription automne 2013" (PDF) (in French). Université de Montreal. 30 September 2014. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ↑ "2007 Annual Report. Université de Montréal Accessed 20 October 2008.

- ↑ General overview of Université de Montréal

- 1 2 3 4 "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2018". ShanghaiRanking Consultancy. 2018. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "QS World University Rankings - 2019". QS Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "World University Rankings 2019". Times Higher Education. TES Global. 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Best Global Universities in Canada". U.S. News & World Report. U.S. News & World Report, L.P. October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ↑ Pound, Richard W. (2005). 'Fitzhenry and Whiteside Book of Canadian Facts and Dates'. Fitzhenry and Whiteside.

- ↑ Université de Montréal - Fêtes du 125e - 125 ans d'histoire (1878-2003) (in French)

- 1 2 3 The Canadian Encyclopedia - University

- 1 2 3 4 The Canadian Encyclopedia - Université de Montréal

- ↑ Université de Montréal - Fêtes du 125e - 125 ans d'histoire (1878-2003) (in French)

- 1 2 3 Université de Montréal - English - Brief History

- ↑ Université de Montréal - Information générale Archived 13 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine. (in French)

- ↑ Université de Montréal - Fêtes du 125e - 125 ans d'histoire (1878-2003) (in French)

- ↑ The Canadian Encyclopedia - Architectural Education

- 1 2 Université de Montréal - Fêtes du 125e - 125 ans d'histoire (1878-2003) (in French)

- ↑ Université de Montréal - Fêtes du 125e - 125 ans d'histoire (1878-2003) (in French)

- ↑ Université de Montréal - Fêtes du 125e - 125 ans d'histoire (1878-2003) (in French)

- ↑ Université de Montréal - Fêtes du 125e - 125 ans d'histoire (1878-2003) (in French)

- ↑ Université de Montréal - Fêtes du 125e - 125 ans d'histoire (1878-2003) (in French)

- ↑ "Publicité de la Northmount Land". 1698-1998 CÔTE-DES-NEIGES AU FIL DU TEMPS (in French). La société du troisième centenaire de la Côte-des-Neiges 1698-1998. 6 July 2000. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ↑ Université de Montréal - Fêtes du 125e - 125 ans d'histoire (1878-2003) (in French)

- ↑ "Le pavillon principal de l'UdeM devient le pavillon Roger Gaudry" (PDF) (in French). La Presse. 17 December 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ↑ http://www.cmp-cpm.forces.gc.ca/dhh-dhp/nic-inm/sm-rm/mdsr-rdr-eng.asp?PID=7904 Archived 25 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Alumni - World War II Honour Roll

- ↑ http://www.cmp-cpm.forces.gc.ca/dhh-dhp/nic-inm/sm-rm/mdsr-rdr-eng.asp?PID=7905 Archived 25 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Alumni - war service

- ↑ Université de Montréal - Plan Campus (in French)

- ↑ Croteau, Martin (14 October 2009). "Nouveau campus de l'UdM à Laval". La Presse (in French). Montreal. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ↑ Université de Montréal - Outremont facility project page (in French)

- ↑ "Hôpital Général Canadien No. 6 (Université Laval de Montréal)". Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ↑ "J.-Armand Bombardier Incubator". Polytechnique Montréal. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ↑ "Université de Montréal" (in French). Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada. 2012. Archived from the original on 21 February 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "Aide financière du Québec" (in French). Université de Montréal. Archived from the original on 24 February 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "ARWU World Top 500 Candidates 2018". ShanghaiRanking Consultancy. 2018. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- ↑ "The Global University Employability Ranking 2017". Times Higher Education. TES Global. 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- 1 2 "University Rankings 2019: Canada's top Medical/Doctoral schools". Maclean's. Rogers Media. 11 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ↑ "Canada's Top School by Reputation 2019". Maclean's. Rogers Media. 11 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ↑ "11 universities bail out of Maclean's survey". CBC News. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 14 April 2006. Archived from the original on 26 June 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ "The 2011 Maclean's Law School Rankings". Maclean's. Rogers Publishing Limited. 15 September 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/2018/subject-ranking/computer-science#!/page/0/length/25/locations/CA/sort_by/rank/sort_order/asc/cols/stats

- ↑ Badenhausen, Kurt (27 July 2011). "Best International 1-year MBA Programs". Forbes LLC. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ↑ "Masters in Management 2011". The Financial Times Ltd. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ↑ "Los Mejores MBA mde Mundo 2011". Cable News Network (in Spanish). Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. 2011. Archived from the original on 20 April 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "North America ranking". The Economist. The Economist Newspaper Limited. 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "The Best International B-Schools of 2010". Bloomberg Businessweek. Bloomberg L.P. 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "Regional ratings: QS Global 200 Business Schools Report 2012". QS Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "What business leaders say". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. 20 October 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "Canada's Top 50 Research Universities 2013" (PDF). RE$EARCH Infosource Inc. 2013. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ↑ "2010 World University Rankings". High Impact Universities. 2010. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "2010 Faculty Rankings For Medicine, Dentistry, Pharmacology, and Health Sciences". High Impact Universities. 2010. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "2010 Faculty Rankings For Life, Biological, and Agricultural Sciences". High Impact Universities. 2010. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "Canada". Higher Education Evaluation and Accreditation Council of Taiwan. Archived from the original on 14 July 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ↑ "Life Sciences: Top Universities in Canada". National Taiwan University. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "Clinical Medicine: Top Universities in Canada". National Taiwan University. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "Social Science: Top Universities in Canada". National Taiwan University. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ Jarvey, Paul; Usher, Alex (August 2012). "Measuring Academic Research in Canada: Field-Normalized Academic Rankings 2012" (pdf). Higher Education Strategy Associates. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ↑ "Qu'est-ce que la FAÉCUM?" (in French). FAÉCUM. 2012. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "Welcome to AEMD!" (in French). Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "Histoire de la Fédération" (in French). FAÉCUM. 2012. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "Associations membres" (in French). FAÉCUM. 2012. Archived from the original on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "Groupes d'intérêt" (in French). FAÉCUM. 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "Quartier Libre" (in French). Quartier Libre. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "A Propos" (in French). CISM 89.3 FM. 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "Historique" (in French). CISM 89.3 FM. 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "Historique" (in French). Canal Savoir. 2009. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "Carabins" (in French). Université de Montréal. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "Historique" (in French). Université de Montréal. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- 1 2 "Centre sportif - CEPSUM - Installations" (in French). Université de Montréal. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "Diplômés de l'Université de Montréal" (in French). Université de Montréal. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ "Philippe de Gaspé Beaubien". Business Families Foundation. 2010. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ "Louis R. Chênevert, Chairman & Chief Executive Officer". United Technologies Corporation. 2014. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ↑ "PIERRE KARL PÉLADEAU". Quebecor. 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ Shorter, Edward; Fink, Max (2010). Endocrine Psychiatry: Solving the Riddle of Melancholia. Oxford University Press. p. 107. ISBN 0-19-973746-0.

- ↑ John, Wilson (2005). Pakistan's nuclear underworld: an investigation. Saṁskṛiti in association with Observer Research Foundation. p. 88. ISBN 81-87374-34-9.

- ↑ "Jocelyn Faubert". Université de Montréal. 2010. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ Herzberg runner-up: Gilles Brassard, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- ↑ Adu-Febiri, Francis; Everett, Ofori (2009). Succeeding from the Margins of Canadian Society: A Strategic Resource for New Immigrants, Refugees and International Students. CCB Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 1-926585-27-5.

- ↑ Hireche, Aïssa (1 April 2013). "Six ex-chefs de gouvernement sur la ligne de départ?". L'Expression (in French). Sarl Fattani Communication and Press. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ↑ Coucill, Irma (2005). Canada's Prime Ministers, Governors General and Fathers of Confederation. Pembroke Publishers Limited. p. 38. ISBN 1-55138-185-0.

- 1 2 Levine, Allan Gerald (1989). Your Worship: the lives of eight of Canada's most unforgettable mayors. James Lorimer & Company. p. 152. ISBN 1-55028-209-3.

- ↑ "Robert BOURASSA" (in French). Assemblee Nationale de Quebec. April 2009. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ Paulin, Marguerite (2005). Maurice Duplessis: powerbroker, politician. Dundurn Press Limited. p. 2. ISBN 1-894852-17-6.

- ↑ "Lomer GOUIN" (in French). Assemblee Nationale de Quebec. March 2009. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ "Daniel JOHNSON (FILS)" (in French). Assemblee Nationale de Quebec. June 2010. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ "Pierre Marc JOHNSON" (in French). Assemblee Nationale de Quebec. May 2010. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ "Bernard LANDRY" (in French). Assemblee Nationale de Quebec. April 2009. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ "Jacques PARIZEAU" (in French). Assemblee Nationale de Quebec. December 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ "Joseph-Mignault-Paul SAUVÉ" (in French). Assemblee Nationale de Quebec. July 2009. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

Further reading

- Bizier, Hélène-Andrée. 1993. L'Université de Montréal: la quête du savoir. Montréal: Libre expression. 311 pp. ISBN 2-89111-522-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Université de Montréal. |