Edward Cornwallis

| Lieutenant-General Edward Cornwallis | |

|---|---|

Edward Cornwallis by Joshua Reynolds (1756) | |

| Governor of Nova Scotia | |

|

In office 1749–1752 | |

| Monarch | George II |

| Preceded by | Richard Philipps |

| Succeeded by | Peregrine Hopson |

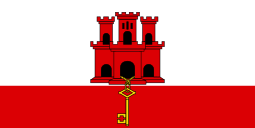

| Governor of Gibraltar | |

|

In office 14 June 1761 – 1 January 1776 | |

| Monarch | George II |

| Preceded by | Earl of Home |

| Succeeded by | Baron Heathfield |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

5 March 1713 London, England |

| Died |

14 January 1776 (aged 62) Gibraltar |

| Resting place | Culford |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Townshend |

| Relations |

Charles Cornwallis, 3rd Baron Cornwallis (grandfather) Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis (nephew) James Cornwallis, 4th Earl Cornwallis (nephew) William Cornwallis (nephew) Frederick Cornwallis (brother) Stephen Cornwallis (brother) Charles Cornwallis, 1st Earl Cornwallis (brother) |

| Children | Charles, Charlotte |

| Father | Charles Cornwallis, 4th Baron Cornwallis |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch | British Army |

| Years of service | 1730s–1776 |

| Rank | Lieutenant General |

| Unit | 8th Foot |

| Commands | 20th Foot, 40th Foot, 24th Foot |

| Battles/wars |

War of the Austrian Succession Father Le Loutre's War Seven Years' War |

Lieutenant General Edward Cornwallis (5 March 1713 – 14 January 1776) was a British military officer who was a member of the aristocratic Cornwallis family. Cornwallis fought in Scotland, putting down the Jacobite rebellion of 1745 and then was given the task of establishing Halifax, Nova Scotia as the Governor of Nova Scotia (1749–1752).[1] Cornwallis returned to London, where he was elected as MP for Westminster and married the niece of Robert Walpole, Great Britain's first Prime Minister. Cornwallis was then given the position of Governor of Gibraltar.

Cornwallis is remembered in the naming of rivers, parks, streets, towns, and buildings in Nova Scotia. However, the honouring of Cornwallis has become controversial in Nova Scotia.[2] Local Mi’kmaq leaders objected to Cornwallis' violent colonial legacy, primarily a scalping bounty he signed in 1749 declaring "a reward of ten Guineas be granted for every Indian Micmac taken or killed." A statue of Cornwallis in a downtown park in Halifax was removed. The Halifax Regional School Board removed his name from a junior high school and other institutions are considering similar measures.

Early life

He was the sixth son of Charles, 4th Baron Cornwallis, and Lady Charlotte Butler, daughter of the Earl of Arran.[3] The Cornwallis family possessed estates at Culford in Suffolk and the Channel Islands.[3] His grandfather, Charles Cornwallis, 3rd Baron Cornwallis, was First Lord of the Admiralty. His nephews were Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, James Cornwallis, 4th Earl Cornwallis, and William Cornwallis.

He and his twin brother, Frederick Cornwallis, were made royal pages at the age of 12.[3] They were enrolled at Eton at age 14. Their brother, Stephen Cornwallis, rose to the rank of General in the Army.

It was initially unclear which brother would enter the church and which the military. The matter was decided when, one day, Frederick fell and paralysed his arm; he would take the religious path.[4]

At age 18, Edward was commissioned into the 47th Regiment of Foot in 1731.[3]

Military career

War of the Austrian Succession

Cornwallis participated in the Battle of Fontenoy during the War of the Austrian Succession. He fought under Colonel Craig, who was killed in action. Cornwallis took over command of the regiment and organised a retreat. Cornwallis's regiment lost eight officers and 385 men. While the retreat was respected by the military, the British public mocked Cornwallis and the other leaders.[5]

Cornwallis played an important role in suppressing the Jacobite rising of 1745.[3] He fought for the victorious, government soldiers at the Battle of Culloden and then led a regiment of 320 men north for the Pacification of the Scottish Highlands. The Duke of Cumberland ordered him to "plunder, burn and destroy through all the west part of Invernesshire called Lochaber." Cumberland added: "You have positive orders to bring no more prisoners to the camp."[6] Cumberland's' campaign was later described by one historian as one of unrestrained violence.[7] Cornwallis ordered his men to chase off livestock, destroy crops and food stores.[8] Against Cornwallis' orders, there was an incident in which some of soldiers raped and murdered non-combatants to intimidate Jacobites from further rebellion.[9]

In 1747 he was made a Groom of the Bedchamber serving in the households of both George II and George III until 1764.

Founding of Halifax

_by_Dominic_Serres%2C_c._1765.jpg)

The British Government appointed Cornwallis as Governor of Nova Scotia with the task of establishing a new British settlement to counter France's Fortress Louisbourg. He sailed from England aboard HMS Sphinx of 14 May 1749, followed by a settlement expedition of 15 vessels and about 2500 settlers. Cornwallis arrived at Chebucto Harbour on 21 June 1749, followed by the rest of the fleet five days later. There was only one death during the passage due to careful preparations, good ventilation and good luck, a remarkable feat when transatlantic expeditions regularly lost large numbers to disease.[10]

Cornwallis was immediately faced with a difficult decision: where to site the town. Settlement organizers in England had recommended Point Pleasant due to its close access to the ocean and ease of defence. His naval advisers opposed the Point Pleasant site due to its lack of shelter and shallows which would not allow ocean-going ships to dock. They wanted the town located at the head of Bedford Basin, a sheltered location with deep water. Others favoured Dartmouth. Cornwallis made the decision to land the settlers and build the town at the site of present-day Downtown Halifax halfway up the harbour with deep water, protected by a defensible hill (later known as Citadel Hill). By 24 July, the plans of the town had been drawn up and on 20 August lots were drawn to award settlers their town plots in a settlement that was to be named "Halifax" after Lord Halifax the President of the Board of Trade and Plantations who had drawn up the expedition plans for the British Government.[11]

Relations with the Wabanaki Confederacy

One of Cornwallis' first priorities was to make peace with the Wabanaki Confederacy, which included the Mi'kmaq. (The Confederacy had been aligned with New France through four wars starting with King William's War.) A group of Maliseet, Passamaquoddy and single band of Mi'kmaq met with Cornwallis in the Summer of 1749. They agreed with the British to end fighting and renewed an earlier 1725 treaty drafted in Boston, redrafted as the Treaty of 1749.[12]

Cornwallis' efforts to have other Mi'kmaq tribes sign treaties were rejected. Most Mi'kmaq leaders in Nova Scotia regarded the unilateral establishment of Halifax as a violation of the 1725 treaty with the Mi'kmaq people, signed after Father Rale's War.[13]

Mi'kmaq leaders met at St. Peters in Cape Breton in September 1749 to respond to British moves. They composed a letter to Cornwallis making it clear that, while they tolerated the small garrison at Annapolis Royal, they completely opposed settlement at Halifax: "The place where you are, where you are building dwellings, where you are now building a fort, where you want, as it were, to enthrone yourself, this land of which you want to make yourself absolute master, this land belongs to me". Thus Mi'kmaq leaders regarded the Halifax settlement as "a great theft that you have perpetrated against me."[14]

A wave of Mi'kmaq attacks began immediately afterwards. At Chignecto Bay, Mi'kmaq fighters attacked two British ships while two others were seized at Canso. At Halifax, Mi'kmaq attacks began on settlers and soldiers outside the fortified township, beginning with the first of several raids on the longhouse lumbering settlement at Dartmouth across the harbour. Five were killed in the initial attack and one escapee came to bring the news to Cornwallis. His Council met and while they urged either negotiation or a formal declaration of war, Cornwallis took the position that there was no sovereignty to negotiate with or declare war on and that the Mi'kmaq were British subjects and therefore should be considered "rebels."

This stage of the long-running Anglo-Mi'kmaq conflict is known by some historians as Father Le Loutre's War.

Father Le Loutre's War

When Cornwallis arrived in Halifax, there was a long history of frontier warfare in Acadia and Nova Scotia between the British and the Wabanaki Confederacy (which included the Mi'kmaq). The Mi'kmaq sought to protect their land by killing British civilians along the New England/Acadia border in present-day Maine (See the Northeast Coast Campaigns 1688, 1703, 1723, 1724, 1745, 1746, 1747).[15][13][16] Despite the end of King George's War by the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, there was renewed fighting in Acadia during Cornwallis' governorship, which was called Father Le Loutre's War.

Cornwallis sought to project British military power by establishing forts in the largest Acadian communities, at Pisiguit (Windsor) (Fort Edward), Grand Pré (Fort Vieux Logis), and Chignecto (Fort Lawrence). The fighting started when Acadians and Mi'kmaq responded by attacking the British at Chignecto, Grand Pré, Dartmouth, Canso, and Halifax. The French erected forts at present day Saint John, Chignecto (Fort Beauséjour), and Port Elgin, New Brunswick. Cornwallis's forces attacked the Mi'kmaq and Acadians at Mirligueche (later known as Lunenburg), Chignecto, and St. Croix.

British governors had often issued proclamations against the Mi'kmaq for their raids.[17] After the Raid on Dartmouth, Cornwallis issued a proclamation to separate the two populations, by banning the Mi'kmaq from peninsular Nova Scotia. "Cornwallis proposed "to root [the Micmacs] out entirely," but the board warned him that such a course might imperil neighbouring British colonies by producing "a dangerous spirit of resentment" among other tribe."[18]

In New England, the British paid their Rangers a bounty for Mi'kmaq prisoners or scalps, and the French paid the Wabanaki for British prisoners and scalps.[Note 1] Cornwallis followed New England's example in his proclamation, in which he created a proclamation to harass - "annoy, distress, take or scalp" - the Mi'kmaq to remove them the peninsular Nova Scotia. Within this proclamation he offered a bounty for prisoners or the scalps of Mi'kmaw fighters.[20][21] He later issued a bounty in March 1750 for Mi'kmaw women and children if they were taken prisoners. The bounties were not effective. Cornwallis increased the bounty for Mi'kmaw fighters dramatically in March 1751, but this increase brought in only one scalp in the next four months.[22]

In May 1751, the Mi'kmaw mounted their largest attack on British settlers with the Raid on Dartmouth. With this raid, the Mi'kmaq had stopped British expansion and therefore the Mi'kmaw stopped attacking. Cornwallis interpreted the cessation of attacks as the Mi'kmaq wanting peace. Indeed, Cornwallis laid the foundation for and was at the signing of the Treaty of 1752 with Major Cope. Cornwallis attended the meeting at Cope's request. Having only committed to being Governor for two years, Cornwallis eventually resigned his commission and left the colony in October 1752.[23][24] The treaty was ultimately rejected by most of the other Mi'kmaq leaders. Cope burned the treaty six months after he signed it.[25]

Cornwallis left Nova Scotia in 1752, three years before Father Le Loutre's War ended in 1755, and was appointed Colonel of the 24th Regiment of Foot.

Seven Years' War

In November 1756 Cornwallis was one of three colonels who were ordered to proceed to Gibraltar and from there embark for Menorca, which was then under siege from the French.[3] Admiral John Byng called a council of war, which involved Cornwallis, and advised the return of the fleet to Gibraltar leaving the garrison at Menorca to its fate.[3] Byng, Cornwallis and the other officers were arrested when they returned to England. A large, unruly mob attacked the officers as they left their ships in Portsmouth and later burned effigies of Cornwallis and the other officers.[26]

The officers faced court martial on "suspicion of disobedience of orders and neglect of duty."[27] Byng was found guilty and executed. Cornwallis testified that he had not disobeyed orders, but that it was "impracticable" to land at Menorca due to stiff French defences. Further, he said he was following Byng's command. "I looked upon myself as under the command of the admiral and should have thought it my duty to have obeyed him", he testified.[27] Cornwallis was judged to have been a passenger under the control of Byng and was thus exonerated.

Cornwallis was also one of the senior officers in the September 1757 Raid on Rochefort which saw a failed amphibious descent on the French coastline.[3] The vast force massed on the Isle of Wight before sailing for Rochefort. The fleet stopped at Île D'Aix and examined the French defences. General Sir John Mordaunt, head of the land forces, decided the defences were too strong to attack. He called a council of war. Cornwallis voted to retreat, while Admiral Edward Hawke, head of the naval forces, and James Wolfe, quartermaster general, voted to attack. Mordaunt and Cornwallis carried the day and the mission was abandoned.[28]

Mordaunt was arrested and faced court martial. Cornwallis testified that an attempted landing at Rochefort would have been "dangerous, almost impracticable and madness."[29] James Wolfe wrote to his father in November 1757 and said Cornwallis "...has more zeal, more merit, and more integrity than one commonly meets with among men….Cornwallis is a man of approved courage and fidelity."

Governor of Gibraltar

Cornwallis served as the Governor of Gibraltar from 14 June 1761 to January 1776 when he died at the age of 63.[3] His body was returned to England and laid to rest at Culford Parish Church in Culford, near Bury St. Edmunds on 9 February 1776. Both of his family titles are now extinct. In 1899, MacDonald wrote, "His name is fast coming under the category of ‘Britain's forgotten worthies'."[30]

Personal life

In 1763, Cornwallis married Mary Townshend, daughter of Charles Townshend, 2nd Viscount Townshend and Dorothy Townshend (Walpole), the sister of Robert Walpole. His marriage to Mary did not produce any children. His brother, Charles Cornwallis, 1st Earl Cornwallis married Mary's half sister, Elizabeth, daughter of Charles and his first wife, Elizabeth Pelham. Through his brother's marriage, he became uncle of Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis.[31]

Commemorations in Nova Scotia

Several buildings, (Canadian Forces Base Cornwallis, a former Canadian Forces Base located in Deep Brook, Nova Scotia) places (Cornwallis Street in Halifax, Cornwallis Street in Shelburne, the Cornwallis River, and Cornwallis Park), and landmarks have been named after Cornwallis. A number of ships were named after Cornwallis, including the 1944 harbour ferry Governor Cornwallis and the Canadian Coast Guard Ship Edward Cornwallis. As a tourism initiative, the Edward Cornwallis Statue was erected in 1931 at the center of Cornwallis Park in downtown Halifax, also named for Cornwallis.

These commemorations of Cornwallis have become controversial. Cornwallis Junior High School was renamed Halifax Central Junior High in January 2012,[32] in 2017 the Cornwallis Street Baptist Church announced it would rename itself,[33] and the Cornwallis statue was removed by order of Halifax Regional Council on 30 January 2018.[34]

In popular culture

- Edward Cornwallis is the subject of The Hampton Grease Band song entitled "Halifax" which appears on the double album Music to Eat.

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ ... from 1713 to 1749 Nova Scotia was neglected by England, but the crafty designs of the French to acquire by fraud what they could not obtain by force drew the attention of the British public to the importance of the colony, and encouragements were held out to retired officers, &c. to whom officers of grants of land were made; 3760 adventurers were embarked with their families for the colony; Parliament granted 40,000ℓ. for their support, and they landed at Chebucto harbour, where the town of Halifax was soon erected by the new emigrants under the command of their Governor the Hon. Edward Cornwallis Martin 1837, p.7

- ↑ "Meet the real Edward Cornwallis". The Chronicle Herald. 1 February 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Story – Honorable Edward Cornwallis". www.mastermason.com. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ↑ Tattrie (2013), p. 36

- ↑ Tattrie (2013), p. 20

- ↑ Tattrie (2013), p. 28

- ↑ Plank (2005), p. 67

- ↑ Tattrie (2013), p. 29

- ↑ Tattrie (2013), p. 31

- ↑ Raddall (1948), pp. 24–25

- ↑ Beck, J. Murray (1979). "Cornwallis, Edward". In Halpenny, Francess G. Dictionary of Canadian Biography. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ↑ Patterson (1994), p. 129

- 1 2 Grenier (2008)

- ↑ Johnston (2008), pp. 38–40

- ↑ Tod Scott. Mi'kmaw Armed Resistance to British Expansion in Northern New England (1676–1781). Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society Journal. Vol. 19, 2016. pp. 1-18

- ↑ Reid (2008)

- ↑ Drake (1870), p. 134

- ↑ Beck (1979)

- ↑ See Grenier (2008), p. 152 and Faragher (2005), p. 405.

- ↑ Willick, Frances (15 July 2017). "'Offensive and disgraceful': Protesters cheer as City of Halifax shrouds Cornwallis statue – Nova Scotia – CBC News". CBC.ca. CBC/Radio-Canada. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

Cornwallis, a governor of Nova Scotia, was a military officer who founded Halifax for the British in 1749. The same year, he issued the proclamation, offering a cash bounty to anyone who killed a Mi'kmaq fighter.

- ↑ (Peotto 2018, p. 266)

- ↑ "The London magazine, or, Gentleman's monthly intelligencer v.20 1751". HathiTrust. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ↑ Plank (1996), p. 34

- ↑ "Correspondence of William Shirley : governor of Massachusetts and military commander in America, 1731-1760". archive.org. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ↑ Plank (1996), pp. 33–34

- ↑ Tattrie (2013), p. 212

- 1 2 The Report of the General Officers, Appointed to enquire into the conduct of Major General Stuart, and Colonels Cornwallis and the Earl of Effingham, 8 December 1756.

- ↑ Tattrie (2013), pp. 217–220

- ↑ The Proceedings of a General Court-Martial held at Whitehall upon the Trial of Lieutenant-General Sit John Mordaunt.

- ↑ Tattrie, John (11 March 2012). "Meet the real Edward Cornwallis". The Chronicle Herald. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ↑ "Person Page". www.thepeerage.com. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ↑ "Cornwallis Junior High officially renamed". CTV News. 26 January 2012.

- ↑ Bundale, Brett (17 September 2017). "Black church to cast aside Cornwallis' name". DurhamRegion.com. The Canadian Press. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ↑ "Halifax council votes to remove Cornwallis statue". The Chronicle Herald. 30 January 2018.

Bibliography

- Drake, Samuel Gardner (1870). A Particular History of the Five Years French and Indian War in New England and Parts Adjacent. With William Shirley. Albany, New York: Joe Munsell.

- Faragher, John Mack (2005). A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from Their American Homeland. W. W. Norton. ISBN 9780393051353.

- Gray, Charlotte (2004). The Museum Called Canada: 25 Rooms of Wonder. Random House. ISBN 9780679312208.

- Grenier, John (2008). The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710–1760. Oklahoma University Press.

- Grenier, John (2005). The first way of war: American war making on the frontier, 1607–1814. Cambridge University Press.

- Johnston, A. J. B. (2008). Endgame 1758: The Promise, the Glory, and the Despair of Louisbourg's Last Decade. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803260092.

- Martin, Robert Montogomery (1837). History of Nova Scotia, Cape Breton, the Sable Islands, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, the Bermudas, Newfoundland, &c., &c. Whittaker & Company.

- Beck, J. Murray (1979). "Cornwallis, Edward". In Halpenny, Francess G. Dictionary of Canadian Biography. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Patterson, Stephen (1994). "1744–1763: Colonial Wars and Aboriginal Peoples". In Phillip A. Buckner & John G. Reid. The Atlantic Region to Confederation. University of Toronto Press. pp. 125–155. ISBN 9780802069771.

- Peotto, Thomas (January 2018). Dark Mimesis : a cultural history of the scalping paradigm (PDF) (Thesis). Vancouver: University of British Columbia. Lay summary.

The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (History)

- Plank, Geoffrey (1996). "The two Majors Cope: the boundaries of nationality in mid-18th century Nova Scotia". Acadiensis. XXV (2): 18–40.

- Plank, Geoffrey (2001). An Unsettled Conquest: The British Campaign Against the Peoples of Acadia. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812235715.

- Plank, Geoffrey (2005). "New England soldiers in the Saint John River valley: 1758–1760". In Stephen J. Hornsby & John G. Reid. New England and the Maritime Provinces: Connections and Comparisons. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 59–73. ISBN 9780773528659.

- Raddall, Thomas Head (1948). Halifax: Warden of the North. McClelland & Stewart.

- Reid, John G. (2008). "Amerindian power in the early modern Northeast: a reappraisal". Essays on Northeastern North America: Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802091376.

- Tattrie, Jon (2013). Cornwallis: The Violent Birth of Halifax. Pottersfield Press. ISBN 9781897426487.

External links

- Documentary on Cornwallis Statue – CBC Radio – Maritime Magazine Archives

- Centre Acadien (1996)

- Cornwallis – Founder of Freemasonry in Halifax

| Parliament of Great Britain | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Stephen Cornwallis John Cornwallis |

Member of Parliament for Eye 1743–1749 With: John Cornwallis 1743–1747 Roger Townshend 1747–1748 Nicholas Hardinge 1748–1749 |

Succeeded by Nicholas Hardinge Courthorpe Clayton |

| Preceded by Viscount Trentham Sir Peter Warren |

Member of Parliament for Westminster 1753–1762 With: Viscount Trentham 1753–1754 Sir John Crosse 1754–1761 Viscount Pulteney 1761–1762 |

Succeeded by Viscount Pulteney Hon. Edwin Sandys |

| Military offices | ||

| Preceded by Richard Philipps |

Governor of Nova Scotia 1749–1752 |

Succeeded by Peregrine Hopson |

| Preceded by Richard Philipps |

Colonel of the 40th Regiment of Foot 1750–1752 |

Succeeded by Peregrine Hopson |

| Preceded by The Marquess of Lothian |

Colonel of the 24th Regiment of Foot 1752–1776 |

Succeeded by William Taylor |

| Preceded by The Earl of Home |

Governor of Gibraltar 1761–1776 |

Succeeded by Sir John Irwin |