Eddystone Lighthouse

An aerial view of the fourth lighthouse.

(The stub of the third lighthouse is visible in the background.) | |

Devon | |

| Location |

offshore Rame Head Cornwall England |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 50°10′47.99″N 04°15′53.99″W / 50.1799972°N 4.2649972°WCoordinates: 50°10′47.99″N 04°15′53.99″W / 50.1799972°N 4.2649972°W |

| Year first constructed |

1698 (first) 1709 (second) 1759 (third) |

| Year first lit | 1882 (current) |

| Automated | 1982 |

| Deactivated |

1703 (first) 1755 (second) 1877 (third) |

| Construction |

wooden tower (first and second) granite tower (third and current) |

| Tower shape |

octagonal tower (first) dodecagonal tower (second) tapered cylindrical tower (third) tapered cylindrical tower with lantern and helipad on the top (current) |

| Height |

18 metres (59 ft) (first) 21 metres (69 ft) (second) 22 metres (72 ft) (third) 49 metres (161 ft) (current) |

| Focal height | 41 metres (135 ft) |

| Current lens | 4th order 250 mm rotating |

| Light source | solar power |

| Intensity | 26,200 candela |

| Range | 17 nautical miles (31 km) |

| Characteristic |

Fl (2) W 10s. Iso R 10s. at 28 metres (92 ft) focal height |

| Fog signal | one blast every 30s. |

| Racon |

T |

| Admiralty number | A0098 |

| NGA number | 0132 |

| ARLHS number | ENG 039 |

| Managing agent |

Trinity House [1] [2] |

The Eddystone Lighthouse is on the dangerous Eddystone Rocks, 9 statute miles (14 km) south of Rame Head, England, United Kingdom. While Rame Head is in Cornwall, the rocks are in Devon[3] and composed of Precambrian gneiss.[4]

The current structure is the fourth to be built on the site. The first and second were destroyed by storm and fire. The third, also known as Smeaton's Tower, is the best known because of its influence on lighthouse design and its importance in the development of concrete for building. Its upper portions have been re-erected in Plymouth as a monument.[5] The first lighthouse, completed in 1699, was the world's first open ocean lighthouse although the Cordouan lighthouse preceded it as the first offshore lighthouse.[6]

The need for a light

The Eddystone Rocks are an extensive reef approximately 12 miles (19 km) SSW of Plymouth Sound, one of the most important naval harbours of England, and midway between Lizard Point, Cornwall and Start Point. They are submerged at high spring tides and were so feared by mariners entering the English Channel that they often hugged the coast of France to avoid the danger, which thus resulted not only in shipwrecks locally, but on the rocks of the north coast of France and the Channel Islands.[7] Given the difficulty of gaining a foothold on the rocks particularly in the predominant swell it was a long time before anyone attempted to place any warning on them.

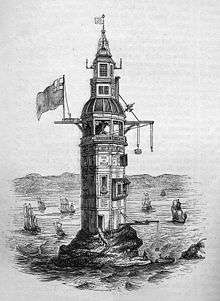

Winstanley's lighthouse

The first lighthouse on Eddystone Rocks was an octagonal wooden structure built by Henry Winstanley. The lighthouse was also the first recorded instance of an offshore lighthouse.[6] Construction started in 1696 and the light was lit on 14 November 1698. During construction, a French privateer took Winstanley prisoner and destroyed the work done so far on the foundations, causing Louis XIV to order Winstanley's release with the words "France is at war with England, not with humanity".[5]

The lighthouse survived its first winter but was in need of repair, and was subsequently changed to a dodecagonal (12 sided) stone clad exterior on a timber framed construction with an octagonal top section as can be seen in the later drawings or paintings. This gives rise to the claims that there have been five lighthouses on Eddystone Rock. Winstanley's tower lasted until the Great Storm of 1703 erased almost all trace on 27 November. Winstanley was on the lighthouse, completing additions to the structure. No trace was found of him, or of the other five men in the lighthouse.[8][9]

The cost of construction and five years' maintenance totalled £7,814 7s.6d, during which time dues totalling £4,721 19s.3d had been collected at one penny per ton from passing vessels.

Rudyard's lighthouse

Following the destruction of the first lighthouse, Captain John Lovett[10][note 1] acquired the lease of the rock, and by Act of Parliament was allowed to charge passing ships a toll of one penny per ton. He commissioned John Rudyard (or Rudyerd) to design the new lighthouse, built as a conical wooden structure around a core of brick and concrete. A temporary light was first shone from it in 1708[11] and the work was completed in 1709. This proved more durable, surviving nearly fifty years.[5]

On the night of 2 December 1755, the top of the lantern caught fire, probably through a spark from one of the candles used to illuminate the light. The three keepers threw water upwards from a bucket but were driven onto the rock and were rescued by boat as the tower burnt down. Keeper Henry Hall, who was 94 at the time, died from ingesting molten lead from the lantern roof.[5] A report on this case was submitted to the Royal Society by physician Edward Spry,[12] and the piece of lead is now in the collections of the National Museums of Scotland.[13]

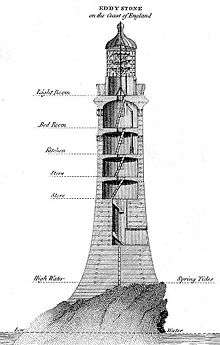

Smeaton's lighthouse

The third lighthouse marked a major step forward in the design of such structures.

Recommended by the Royal Society, civil engineer John Smeaton modelled the shape on an oak tree, built of granite blocks. He pioneered 'hydraulic lime', a concrete that cured under water, and developed a technique of securing the granite blocks using dovetail joints and marble dowels. Construction started in 1756 at Millbay[14] and the light was first lit on 16 October 1759.[5]

Smeaton's lighthouse was 59 feet (18 m) high and had a diameter at the base of 26 feet (8 m) and at the top of 17 feet (5 m).

In 1841 major renovations were made,[15] under the direction of engineer Henry Norris of Messrs. Walker & Burges, including complete repointing, replacement water tanks and filling of a large cavity in the rock close to the foundations. It remained in use until 1877 when erosion to the rocks under the lighthouse caused it to shake from side to side whenever large waves hit.[16] Smeaton's lighthouse was rebuilt on Plymouth Hoe, in Plymouth, as a memorial. William Tregarthen Douglass supervised the dismantling and removal of Smeaton's Tower. The re-erected tower on the Hoe is now a tourist attraction.

The foundations and stub of the tower remain, close to the new and more solid foundations of the current lighthouse[5] – the foundations proved too strong to be dismantled so the Victorians left them where they stood.

An 1850 replica of Smeaton's lighthouse, Hoad Monument, stands above the town of Ulverston, Cumbria as a memorial to naval administrator Sir John Barrow.

Douglass's lighthouse

The current, fourth, lighthouse was designed by James Douglass, using Robert Stevenson's developments of Smeaton's techniques. By April 1879 the new site, on the South Rock was being prepared during the 3½ hours between ebb and flood tide. The supply ship Hercules was based at Oreston, now a suburb of Plymouth, and the stone was prepared at the Oreston yard and supplied from the works of Messrs Shearer, Smith and Co of Wadebridge.[17][18]

The light was lit in 1882 and is still in use. It was automated in 1982, the first Trinity House 'Rock' (or offshore) lighthouse to be converted. The tower has been changed by construction of a helipad above the lantern, to allow maintenance crews access.[19] The helipad has a weight limit of 3600kg.

The tower is 49 metres (161 ft) high, and its white light flashes twice every 10 seconds. The light is visible to 22 nautical miles (41 km), and is supplemented by a foghorn of 3 blasts every 62 seconds.[5]

References in media

- The lighthouse inspired a sea shanty, frequently recorded, that begins "My father was the keeper of the Eddystone light / And he slept with a mermaid one fine night / From this union there came three / A porpoise and a porgy and the other was me!".[20] Another version has the fourth line as "Two of them were fishes and the other was me." There are several verses.

- The lighthouse has been used as a metaphor for stability.[21]

- In the Goon Show episode Ten Snowballs that shook the World (1958), Neddie Seagoon is sent to Eddystone Lighthouse to warn the inhabitants that Sterling has dropped from F-sharp to E-flat.

- The lighthouse is celebrated in the opening and closing movements of Ron Goodwin's Drake 400 Suite. The movement's main theme was directly inspired by the lighthouse's unique light characteristic.[22]

- A novel based on the building of Smeaton's lighthouse, containing many details of the construction, was published in 2005.[23]

- The lighthouse is referenced twice in Herman Melville's epic novel Moby-Dick; at the beginning of Chapter 14, "Nantucket": "How it stands there, away off shore, more lonely than the Eddystone lighthouse.", and in Chapter 133, "The Chase – First Day": "So, in a gale, the but half baffled Channel billows only recoil from the base of the Eddystone, triumphantly to overleap its summit with their scud."

- The lighthouse is referred to in "Daddy was a Ballplayer" by the Canadian band Stringband, and follows a similar line to the sea shanty.

- "The Most Famous of All Lighthouses," the third chapter of The Story of Lighthouses (Norton 1965) by Mary Ellen Chase, is devoted to the Eddystone Lighthouse.

- Eddystone Lighthouse was used for many of the exteriors shots in The Phantom Light, a 1935 film directed by Michael Powell.[24]

Gallery

Clouds over Hoe

Clouds over Hoe

Tinside Pool, Plymouth Sound

Tinside Pool, Plymouth Sound Sunlight through the lantern room

Sunlight through the lantern room Smeaton's Lighthouse, now re-erected on Plymouth Hoe.

Smeaton's Lighthouse, now re-erected on Plymouth Hoe. Painting by John Lynn of Smeaton's Lighthouse

Painting by John Lynn of Smeaton's Lighthouse Sections of Douglass's lighthouse in 1884

Sections of Douglass's lighthouse in 1884

See also

Notes

- ↑ Later Colonel John Lovett (c. 1660–1710) of Liscombe Park Buckinghamshire and Corfe, (son and heir of former merchant in Turkey, Christopher Lovett, lord mayor of Dublin 1676–1677) and uncle of noted architect Edward Lovett Pearce 1699–1733.

References

- ↑ Eddystone The Lighthouse Directory. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved April 30, 2016

- ↑ Eddystone Lighthouse Trinity House. Retrieved April 30, 2016

- ↑ Ordnance Survey mapping; the rocks form part of the unitary district of the City of Plymouth, in the ceremonial county of Devon

- ↑ "Get A Map". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 6 September 2006. View at 1:50000 scale

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Eddystone history". Trinity House. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- 1 2 "Lighthouse". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ Smiles, Samuel (1861). The Lives of the Engineers. Vol 2. p. 16.

- ↑ "Eddystone Lighthouse History". Eddystone Tatler Ltd. Archived from the original on 2 May 2006. Retrieved 7 September 2006.

- ↑ "The Great Storm of 1703". BBC. Archived from the original on 30 August 2006. Retrieved 7 September 2006.

- ↑ Whyman, Susan E. (1999). Sociability and Power in Late-Stuart England: The Cultural Worlds of the ... Oxford University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-19-925023-3.

- ↑ Majdalany, Fred (1959). The Red Rocks of Eddystone. London: Longmans. p. 86.

- ↑ Spry, Edward; John Huxham (1755–56). "An Account of the Case of a Man Who Died of the Effects of the Fire at Eddy-Stone Light-House. By Mr. Edward Spry, Surgeon at Plymouth". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 49: 477–484. doi:10.1098/rstl.1755.0066. JSTOR 104958.

- ↑ Palmer, Mike (2005). Eddystone: the Finger of Light (2nd ed.). Woodbridge, Suffolk: Seafarer Books. ISBN 0-9547062-0-X.

- ↑ Langley, Martin (1987). Millbay Docks (Port of Plymouth series). Exeter: Devon Books. p. 2. ISBN 0-86114-806-1.

- ↑ Woolmer's Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 15 May 1841

- ↑ Douglass, James Nicholas (1878). "Note on the Eddystone Lighthouse". Minutes of proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers. vol. 53, part 3. London: Institution of Civil Engineers. pp. 247–248.

- ↑ "Commencement and Progress of the Eddystone". The Cornishman (40). 17 April 1879. p. 6.

- ↑ "The New Eddystone Lighthouse". The Cornishman (49). 19 June 1879. p. 3.

- ↑ "Eddystone Lighthouse". Trinity House. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ↑ "The Eddystone Light". Retrieved 11 April 2008.

- ↑ Thomas D'Arcy McGee commented that Canada's foundations were as "strong as the foundations of Eddystone" in The Globe, 31 October 1864, 4.

- ↑ CD insert, "British Light Music: Ron Goodwin. 633 Squadron, Drake 400 Suite, and others. New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, Ron Goodwin, conductor." Marco Polo CD 8.223518

- ↑ Severn, Christopher (2005). Smeaton's Tower. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Seafarer Books. ISBN 0-9542750-9-8.

- ↑ "Beacons in the Dark: Lighthouse Iconography in Wartime British Cinema"

Further reading

- Hart-Davis, Adam; Troscianko, Emily (2002). Henry Winstanley and the Eddystone Lighthouse. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-1835-7.

John Smeaton – A Narrative of the Building and Description of the Eddystone Lighthouse with Stone – London 1793

Palmer, Mike; Eddystone, The Finger of Light – First published by Palmridge Publishing in 1998 – Revised edition published in 2005 by Seafarer Books & Globe Pequot Press / Sheridan House – Copyright © 2005 by Mike Palmer All rights reserved – ISBN 0 9547062 0 X

Eddystone The Finger of Light is also a revised Kindle ebook edition, which was released on March 29, 2016.