Earth Overshoot Day

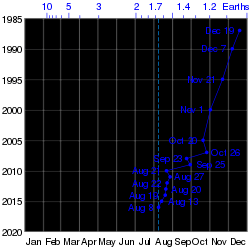

| Year | Overshoot Date | Year | Overshoot Date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | December 19 | 2013 | August 20 | |

| 1990 | December 7 | 2014 | August 19 | |

| 1995 | November 21 | 2015 | August 13 | |

| 2000 | November 1 | 2016 | August 8 | |

| 2005 | October 20 | 2017 | August 2 | |

| 2010 | August 21 | 2018 | August 1 | |

| 2011 | August 27 | 2019 | ||

| 2012 | August 22 | 2020 |

Earth Overshoot Day (EOD), previously known as Ecological Debt Day (EDD), is the calculated illustrative calendar date on which humanity’s resource consumption for the year exceeds Earth’s capacity to regenerate those resources that year. Earth Overshoot Day is calculated by dividing the world biocapacity (the amount of natural resources generated by Earth that year), by the world ecological footprint (humanity's consumption of Earth’s natural resources for that year), and multiplying by 365, the number of days in one Gregorian common calendar year:

When viewed through an economic perspective, EOD represents the day in which humanity enters an ecological deficit spending. In ecology the term Earth Overshoot Day illustrates the level by which human population overshoots its environment. In 2018, Earth Overshoot Day is on August 1.[1]

Earth Overshoot Day is calculated by Global Footprint Network and is a campaign supported by dozens of other nonprofit organizations.[2] Information about Global Footprint Network's calculations[3] and national Ecological Footprints[4] are available online.

Background

Andrew Simms of UK think tank New Economics Foundation originally developed the concept of Earth Overshoot Day. Global Footprint Network, a partner organization of New Economics Foundation, launches a campaign every year for Earth Overshoot Day to raise awareness of Earth’s limited resources. Global Footprint Network measures humanity’s demand for and supply of natural resources and ecological services. Global Footprint Network estimates that in less than eight months, we demand more renewable resources and CO2 sequestration than what the planet can provide for an entire year.[2]

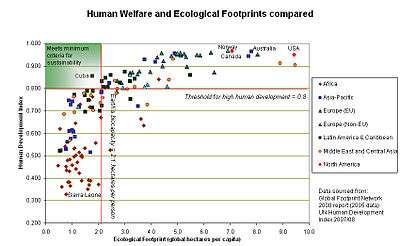

Throughout most of history, humanity has used nature’s resources to build cities and roads, to provide food and create products, and to release carbon dioxide at a rate that was well within Earth’s budget. But by the early 1970s, that critical threshold had been crossed: Human consumption began outstripping what the planet could reproduce. According to Global Footprint Network’s calculations, our demand for renewable ecological resources and the services they provide is now equivalent to that of more than 1.5 Earths. The data shows us on track to require the resources of two planets well before mid-2000-century.

Advocates for Earth Overshoot Day note that the costs of ecological overspending are becoming more evident over time. Climate change — a result of greenhouse gases being emitted faster than they can be absorbed by forests and oceans — is the most obvious result and widespread effects. Other cited effects include: shrinking forests, species loss, fisheries collapse, higher commodity prices and civil unrest.[2]

Criticism

The Breakthrough Institute regards the idea of Earth Overshoot Day and how many Earths we consume as "a nice publicity stunt".[6] According to United Nations data, forests and fisheries are, as a whole, regenerating faster than they are depleted (but admitting that "the surplus might be more a reflection of poor UN fisheries data than healthy fisheries"), while cropland and pasture use is equal to what is available.[6] Hence, Earth Overshoot Day does a poor job at measuring water and land mismanagement (e.g., soil erosion) and only highlights the excess of carbon dioxide that humanity releases above what the ecosystem can absorb. In other words, the additional equivalent number of Earths that humanity requires is equivalent to land area that, if filled with carbon sinks like forests, would balance carbon dioxide emissions.

Global Footprint Network points out that the ecological footprint makes apparent the gap between human demand and regeneration. Essentially, the sum of all demands competing for the planet's regeneration are now exceeding what the planet renews. While the accounting can be improved, and more details added, in its current applications to countries, the accounts typically underestimate human demand as not all aspects are measured (there are gaps in UN data). They also overestimate biocapacity because it is ambiguous to determine how much of current yields is enabled by reduced future yield (for instance as in the case of overuse of groundwater, or erosion). Therefore current accounts underplay the overall ecological deficit or overshoot at the global level. This is discussed in more detail in two chapters of the Routledge Handbook of Sustainability Indicators (Wackernagel et al. 2018 a and b).[7]

Therefore, ecological footprint accounts are metrics that merely define minimal conditions for sustainability. They do not cover all material aspects of sustainability, just a basic, minimal condition for living within the regenerative capacity of the planet’s ecosystems.

In response to the Breakthrough Institute Report, Mathis Wackernagel, founder and president of the Global Footprint Network, also points out that depletion of crop land, for instance, could be included in the Ecological Footprint accounts informing Earth Overshoot Day. But such improvements would "require data sets that do not exist within the UN data set". And such improvements would show an even larger global overshoot. Similarly, the apparent fishery surplus "might be more a reflection of poor UN fisheries data than healthy fisheries".[6]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ "Past Earth Overshoot Days". Retrieved 2018-08-06.

- 1 2 3 "About Earth Overshoot Day". Global Footprint Network. Retrieved July 15, 2018.

- ↑ "Ecological Footprint: data and accounting methodology".

- ↑ "Biocapacity and Ecological Footprint: open data platform".

- ↑ "Sustainable Development: Sustainable development is successful only when it improves citizens' well-being without degrading the environment". Global Footprint Network.

- 1 2 3 Pearce, Fred. "Admit it: we can't measure our ecological footprint". New Scientist. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ↑ Wackernagel, Mathis; et al. "Handbook of Sustainability Indicators -- Chapter 16 - Ecological Footprint: Principles & Chapter 33 - Ecological Footprint: Criticisms and applications". Routledge 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

Further reading

- Catton, William R. Jr. (1980). "Overshoot: The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change". Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-00818-9.

- Daily, Gretchen C.; Matson, Pamela A. (2008). "Ecosystem services: From theory to implementation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105: 9455–9456. doi:10.1073/pnas.0804960105. PMC 2474530.

- Easterling, William E. (2007). "Climate change and the adequacy of food and timber in the 21st century". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (50): 19679. doi:10.1073/pnas.0710388104. PMC 2148356.

- Friedman, Thomas (2008). Hot, Flat, and Crowded. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-16685-4.

- Khanna, Parag (2008). The Second World. New York: Random House. ISBN 81-7036-406-X.

- "WWF: human consumption is outpacing earth's capacity". EurActiv.com. October 26, 2004.

- Wackernagel, Mathis; Niels B. Schulz, Diana Deumling, Alejandro C. Linares, Martin Jenkins, Valerie Kapos, Chad Monfreda, Jonathan Loh, Norman Myers, Richard Norgaard, and Jorgen Randers (2002). "Tracking the ecological overshoot of the human economy". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99 (14): 9266–9271. doi:10.1073/pnas.142033699. PMC 123129. PMID 12089326.

- Wackernagel, M., A. Galli, L. Hanscom, D. Lin, L. Mailhes, T. Drummond (2018), CHAPTER 16: Ecological Footprint Accounts: Principles” p244-264, in Simon Bell and Stephen Morse (Editors) 2018. Routledge Handbook of Sustainability Indictors, Routledge International Handbooks. Routledge, https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315561103-16

- Wackernagel, M., A. Galli, L. Hanscom, D. Lin, L. Mailhes, T. Drummond (2018), CHAPTER 33: Ecological Footprint Accounts: Criticisms and Applications” p521-539 in Simon Bell and Stephen Morse (Editors) 2018. Routledge Handbook of Sustainability Indictors, Routledge International Handbooks. Routledge, https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315561103-33

External links

- Earth Overshoot Day official website

- Global Footprint Network official website

- Ecological Footprint Explorer Open Data Platform

- Damassa, Tom (October 26, 2006). "Human Consumption Pushing Ecosystems to the Brink". EarthTrends Environmental Information. Archived from the original on 2006-11-09.

- Futehally, Ilmas. "Living Beyond Our Means". Strategic Foresight Group.