Duchy of Saint Sava

| Duchy of Saint Sava Војводство Светог Саве | ||||||

| Ottoman vassal (1435–1444) Aragonese vassal (1444–1466) Ottoman vassal (1469–1483) of present-day Herzegovina | ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

| Capital | Herceg Novi | |||||

| Government | Duchy | |||||

| Historical era | Medieval | |||||

| • | Start of rule | 1435 | ||||

| • | Disestablished | 1483 | ||||

| History of Herzegovina |

|---|

|

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Bosnia and Herzegovina |

|

|

Ottoman era |

|

Habsburgs |

|

|

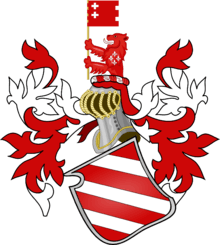

Duchy of Saint Sava (Latin: Ducatus Sancti Sabae,[1] Serbo-Croatian: vojvodstvo Svetog Save, војводство Светог Саве[2][3]) was a late medieval state which existed amid the Ottoman conquest of the Balkans. It was ruled by Stjepan Vukčić and his son Vladislav, of the Kosača noble family, and included parts of modern-day Bosnia & Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro and Serbia.

Stjepan titled himself "Vojvoda of Saint Sava", after the first Serbian Archbishop, Saint Sava. Vojvoda in German translation is Herzog ("duke"), and this would later give the name to the present-day region of Herzegovina, as the Ottomans used Hersek Sancağı ("Sanjak of the Herzog") for the province which was transformed into an Ottoman sanjak.[4]

Background

History

On 15 February 1444, Stephen signed a treaty with Alfonso V, King of Aragon and Naples, becoming his vassal in exchange for the king's help against Stjepan's enemies, namely King Stephen Thomas of Bosnia, Duke Ivaniš Pavlović and the Republic of Venice. In the same treaty Stjepan promised to pay regular tribute to Alfonso instead of his tribute to the Ottoman sultan, which he had done up until then.[5]

In a document sent to Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III on 20 January 1448, Stephen Vukčić Kosača styled himself "Vojvoda (duke, herzog) of Saint Sava", "lord of Hum and the coast", and "Grand Duke", and forced the Bosnian kingdom to recognize him as such.[6][7] The title "Vojvoda of Saint Sava" had considerable public relations value, because Sava's relics, which were located in Mileševa, were consider miracle-working by people of all Christian faiths in the region.[8]

In 1451 Stjepan attacked Dubrovnik, and laid siege to the city.[9] He had earlier been made a Ragusan nobleman and, consequently, the Ragusan government now proclaimed him a traitor.[9] A reward of 15,000 ducats, a palace in Dubrovnik worth 2,000 ducats, and an annual income of 300 ducats was offered to anyone who would kill him, along with the promise of hereditary Ragusan nobility which also helped hold this promise to whoever did the deed.[9] Stjepan was so scared by the threat that he finally raised the siege.[9]

Stjepan Vukčić died in 1466, and was succeeded by his eldest son Vladislav Hercegović. In 1482 he was overpowered by Ottoman forces led by Stjepan Vukčić's youngest son, Hersekli Ahmed Pasha, who converted to Islam prior to that. In the Ottoman Empire, Herzegovina was organized as a province (sanjak) within the state (pashaluk) of Bosnia.

Stjepan founded the Serbian Orthodox Zagrađe Monastery near his realm's seat in Herceg Novi, modern-day Montenegro, and the Savina Monastery, also near Herceg Novi.

Rulers

- Stjepan Vukčić Kosača, 1435–1466

- Vladislav Hercegović, 1466–1483

- Vlatko Hercegović

- Balša Hercegović (titular)

See also

References

- ↑ Caroli Du Fresne domini Du Cange Illyricum vetus & novum, siue, Historia..., p. 126

- ↑ Vasa Čubrilović, Vojne krajine u jugoslovenskim zemljama u novom veku do Karlovačkog mira 1699: zbornik radova sa naučnog skupa održanog 24. i 25. aprila 1986

- ↑ Nebojša Damnjanović, Vladimir Merenik, The first Serbian uprising and the restoration of the Bosniak state, p. 21

- ↑ p. 44

- ↑ Momčilo Spremić, Balkanski vazali kralja Alfonsa Aragonskog, Prekinut uspon, Beograd 2005, pp. 355–358

- ↑ page 756

- ↑ "Duke+of+Saint+Sava" The Danube-Aegean waterway project: a paper

- ↑ Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press. p. 578. ISBN 0-472-08260-4, 9780472082605.

- 1 2 3 4 Krekic (1978), pp. 388–389.

Sources

- Vojne krajine u jugoslovenskim zemljama u novom veku do Karlovačkog mira 1699

- Krekić, Bariša (1978). Contributions of Foreigners to Dubrovnik's Economic Growth in the Late Middle Ages. Viator. 9. pp. 375–94.

- Zdenko Zlatar, The poetics of Slavdom: the mythopoeic foundations of Yugoslavia. p. 555

Further reading

- Mandić, S. H. (2000). Srpske porodice Vojvodstva svetog Save. Gacko.

External links

- Cawley, Charles, Dukes of Herzegovina, Medieval Lands database, Foundation for Medieval Genealogy