Contrabassoon

| |

| Woodwind instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names |

|

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification |

422.112–71 (Double-reeded aerophone with keys) |

| Developed | Mid 18th century |

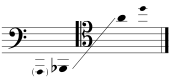

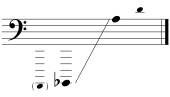

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

The contrabassoon, also known as the double bassoon, or bass bassoon, is a larger version of the bassoon, sounding an octave lower. Its technique is similar to its smaller cousin, with a few notable differences.

Differences from the bassoon

The reed is considerably larger than the bassoon's, at 65–75 mm (2.6–3.0 in) in total length (and 20 mm (0.8 in) in width) as compared to 53–58 mm (2.1–2.3 in) for most bassoon reeds. The large blades allow ample vibration that produces the low register of the instrument. The contrabassoon reed is similar to an average bassoon's in that scraping the reed affects both the intonation and response of the instrument.[1]

The fingering of the contrabassoon is slightly different than that of the bassoon, particularly at the register change and in the extreme high range. The instrument is twice as long, curves around on itself twice, and, due to its weight and shape, is supported by an endpin rather than a seat strap. Additional support is sometimes given by a strap around the player's neck. A wider hand position is also required, as the primary finger keys are widely spaced.

The contrabassoon has a water key to expel condensation and a tuning slide for gross pitch adjustments. The instrument comes in a few pieces (plus bocal); some models cannot be disassembled without a screwdriver. Sometimes, however, the bell can be detached, and instruments with a low A extension often come in two parts.

Range, notation and tone

The contrabassoon is a very deep sounding woodwind instrument that plays in the same sub-bass register as the tuba and the contrabass versions of the clarinet and saxophone. It has a sounding range beginning at B♭0 (or A0, on some instruments) and extending up three octaves and a major third to D4 (although the top fourth is rarely used). Donald Erb and Kalevi Aho write even higher (to A♭4 and C5, respectively) in their concertos for the instrument. The instrument is notated an octave above sounding pitch in bass clef, with tenor or even (rarely) treble clef called for in high passages.

Tonally, it sounds much like the bassoon except for a distinctive organ pedal quality in the lowest octave of its range which provides a solid underpinning to the orchestra or concert band. The lowest range, in comparison with the bassoon, can be played more quietly than the bassoon can. Although the instrument can have a distinct 'buzz', which becomes almost a clatter in the extreme low range, this is nothing more than a variance of tone quality which can be remediated by appropriate reed design changes. While prominent in solo and small ensemble situations, the sound can be completely obscured in the volume of the full orchestra or concert band.

History

Precursors

Precursors to the contrabassoon are documented as early as 1590 in Austria and Germany, at a time when the growing popularity of doubling the bass line led to the development of lower-pitched dulcians. Examples of these low-pitched dulcians include the octavebass, the quintfaggot, and the quartfaggot.[2] There is evidence that a contrafagott was used in Frankfurt in 1626.[3] Baroque precursors to the contrabassoon developed in France in the 1680's, and later in England in the 1690's, independent of the dulcian developments in Austria and Germany during the previous century.[2]

Baroque Era - Present

The contrabassoon was developed, especially in England, in the mid-18th century; the oldest surviving instrument, which came in four parts and has only three keys, was built in 1714.[4] It was around that time that the contrabassoon began gaining acceptance in church music. Some notable early uses of the contrabassoon during this period include in J.S. Bach's St. John's Passion (1723), and G.F. Handel's L'Allegro (1740) and Music for the Royal Fireworks (1749)[3].[2] Until the late 19th century, the instrument typically had a weak tone and poor intonation. For this reason, the contrabass woodwind parts often were scored for, and contrabassoon parts were often played on, serpent, contrabass sarrusophone or, less frequently, reed contrabass, until improvements by Heckel in the late 19th century secured the contrabassoon's place as the standard double reed contrabass.

For more than a century, between 1880 and 2000, Heckel’s design remained relatively unchanged. Chip Owen at the American company, Fox, began manufacturing an instrument in 1971 with some improvements. Generally, during the 20th century changes to the instrument were limited to an upper vent key near the bocal socket, a tuning slide, and a few key linkages to facilitate technical passages. In 2000, Heckel announced a completely new keywork for their instrument and Fox introduced their own new key system based on input from New York Philharmonic contrabassoonist Arlan Fast. Both companies' improvements allow for improved technical facility as well as greater range in the high register.

Current use

Most major orchestras use one contrabassoonist, either as a primary player or a bassoonist who doubles, as do a large number of symphonic bands.

The contrabassoon is a supplementary orchestral instrument and is most frequently found in larger symphonic works, often doubling the bass trombone or tuba at the octave. Frequent exponents of such scoring were Brahms and Mahler, as well as Richard Strauss, and Dmitri Shostakovich. The first composer to write a separate contrabassoon part in a symphony was Beethoven, in his Fifth Symphony (1808) (it can also be heard providing the bass line in the brief "Janissary band" section of the fourth movement of his Symphony No. 9, just prior to the tenor solo), although Bach, Handel (in his Music for the Royal Fireworks), Haydn (e.g., in both of his oratorios The Creation and The Seasons, where the part for the contrabassoon and the bass trombone are mostly, but not always, identical), and Mozart had occasionally used it in other genres (e.g., in the Coronation Mass). Composers have often used the contrabassoon to comical or sinister effect by taking advantage of its seeming "clumsiness" and its sepulchral rattle, respectively. A clear example of this can be heard in Paul Dukas' The Sorcerer's Apprentice (originally scored for contrabass sarrusophone). Igor Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring is one of the few orchestral works that requires two contrabassoons[5].

As a featured instrument, the contrabassoon can be heard in several works, most notably Maurice Ravel's Mother Goose Suite, and at the opening of Piano Concerto for the Left Hand.

Solo literature is somewhat lacking, although some modern composers such as Gunther Schuller, Donald Erb, Michael Tilson Thomas, John Woolrich, Kalevi Aho, and Daniel Dorff have written concertos for this instrument (see below).

Gustav Holst gave the contrabassoon multiple solos in The Planets, primarily in "Mercury, the Winged Messenger" and "Uranus, the Magician".[4]

Notable contrabassoons

Prof. Dr. Werner Schulze of Austria owns a contrabassoon with an extension to A♭0, a half step below the lowest note on the piano.

In 2008, one of only four Fox 950 contrabassoons was stolen from the Colburn School in Los Angeles. The school offered a reward for the US$30,000 instrument, however as of 2015 it is still missing and presumed destroyed.[6]

Notable solos and soloists

Most major symphony orchestras employ a contrabassoons, and many have programmed concerts featuring their contrabassoonist as soloist. For example, Michael Tilson Thomas: Urban Legend for Contrabassoon and Orchestra featuring Steven Braunstein, San Francisco Symphony;[7] Gunther Schuller: Concerto for Contrabassoon featuring Lewis Lipnick, National Symphony Orchestra; John Woolrich: Falling Down featuring Margaret Cookhorn, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra[8]; Erb: Concerto for Contrabassoon featuring Gregg Henegar, London Symphony Orchestra;[9] Kalevi Aho: Concerto for Contrabassoon featuring Lewis Lipnick Bergen Symphony Orchestra[10]

One of the few contrabassoon soloists in the world is Susan Nigro,[11] who lives and works in and around Chicago. Besides occasional gigs with orchestras and other ensembles (including regular substitute with the Chicago Symphony), her main work is as soloist and recording artist. Many works have been written specifically for her, and she has recorded several CDs, including "THE BIG BASSOON","LITTLE TUNES FOR THE BIG BASSOON","THE 2 CONTRAS", "NEW TUNES FOR THE BIG BASSOON","BELLISSIMA", "ORIGINAL TUNES FOR THE BIG BASSOON", "COTT JOPLIN RAGS FOR THE BIG BASSOON" etc.[12]

Henry Skolnick has performed and toured internationally on the instrument. He commissioned, premiered and recorded Aztec Ceremonies for contrabassoon by Graham Waterhouse.[13]

A rare use of the instrument in jazz was by Garvin Bushell, who sat in as a guest with saxophonist John Coltrane during his 1961 recording sessions at the Village Vanguard.

References

- ↑ The Bassoon Reed Manual: Lou Skinner's Theories and Techniques, Chapter 10

- 1 2 3 Kopp, James (2012). The Bassoon. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 188–191. ISBN 978-0-300-11829-2.

- 1 2 Langwill, Lyndesay (1975). The Bassoon and Contrabassoon. Great Britain: Ernest Benn Limited. p. 113. ISBN 0 510-36501-9.

- 1 2 Raimondo Inconis INCONIS, IL CONTROFAGOTTO, Storia e Tecnica - ed. Ricordi (19842004) ER 3008 / ISMN 979-0-041-83008-7

- ↑ https://nyphil.org/~/media/pdfs/watch-listen/commercial-recordings/1213/release01.pdf

- ↑ Raimondo Inconis INCONIS,IL CONTROFAGOTTO, Storia e Tecnica - ed. Ricordi (19842004) ER 3008 / ISMN 979-0-041-83008-7

- ↑ "robertronnes.com". www.robertronnes.com. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "Margaret Cookhorn - City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra". City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. Retrieved 2018-09-27.

- ↑ "The London Philharmonic Celebrates American Composers". 6 July 1990 – via Amazon.

- ↑ ncc.com. "Andrew Litton Insights: Passed Up by the NSO, Concerto For Contrabassoon Premieres in Norway, Feb 2006 - Conductor - Maestro - Music Director - Musician".

- ↑ "Sue Nigro - Contrabassoon".

- ↑ "Crystal Records Susan Nigro Contrabassoon recordings". www.crystalrecords.com. Retrieved 2018-09-27.

- ↑ Bassoon with a View Archived 2011-07-20 at the Wayback Machine. innova.mu

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Contrafagotto. |