Domestic worker

A domestic worker, domestic helper, domestic servant, manservant or menial, is a person who works within the employer's household. Domestic helpers perform a variety of household services for an individual or a family, from providing care for children and elderly dependents to housekeeping, including cleaning and household maintenance. Other responsibilities may include cooking, laundry and ironing, shopping for food and other household errands. Such work has always needed to be done but before the Industrial Revolution and the advent of labour saving devices, it was physically much harder.

Some domestic helpers live within their employer's household. In some cases, the contribution and skill of servants whose work encompassed complex management tasks in large households have been highly valued. However, for the most part, domestic work, while necessary, is demanding and undervalued. Although legislation protecting domestic workers is in place in many countries, it is often not extensively enforced. In many jurisdictions, domestic work is poorly regulated and domestic workers are subject to serious abuses, including slavery.[1]

Servant is an older English word for "domestic worker", though not all servants worked inside the home. Domestic service, or the employment of people for wages in their employer's residence, was sometimes simply called "service" and has often been part of a hierarchical system. In Britain a highly developed system of domestic service peaked towards the close of the Victorian era, perhaps reaching its most complicated and rigidly structured state during the Edwardian period (a period known in the US as the Gilded Age and in France as the Belle Époque), which reflected the limited social mobility before World War I.

Legal protections

The United Kingdom's Master and Servant Act 1823 was the first of its kind and influenced the creation of domestic service laws in other nations, although legislation tended to favour employers. However, before the passing of such Acts servants, and workers in general, had no protection in law. The only real advantage that domestic service provided was the provision of meals, accommodation, and sometimes clothes, in addition to a modest wage. Service was normally an apprentice system with room for advancement through the ranks.

At its 301st Session (March 2008), the International Labour Organization (ILO) Governing Body agreed to place an item on decent work for domestic workers on the agenda of the 99th Session of the International Labour Conference (2010) with a view to the setting of labour standards.[2] The conditions faced by domestic workers have varied considerably throughout history and in the contemporary world. In the course of twentieth-century movements for labour rights, women's rights and immigrant rights, the conditions faced by domestic workers and the problems specific to their class of employment have come to the fore. In 2011, the International Labour Organization adopted the Convention Concerning Decent Work for Domestic Workers.

In July 2011, at the annual International Labour Conference, held by the ILO, conference delegates adopted the Convention on Domestic Workers by a vote of 396 to 16, with 63 abstentions. The Convention recognized domestic workers as workers with the same rights as other workers. On 26 April 2012, Uruguay was the first country to ratify the convention.[3][4]

Accommodation

Many domestic workers are live-in domestics. Though they often have their own quarters, their accommodations are not usually as comfortable as those reserved for the family members. In some cases, they sleep in the kitchen or small rooms, such as a box room, sometimes located in the basement or attic. Domestic workers may live in their own home, though more often they are "live-in" domestics, meaning that they receive their room and board as part of their salaries. In some countries, because of the large gap between urban and rural incomes, and the lack of employment opportunities in the countryside, even an ordinary middle class urban family can afford to employ a full-time live-in servant. The majority of domestic workers in China, Mexico, India, and other populous developing countries, are people from the rural areas who are employed by urban families.

Employers may require their domestic workers to wear a uniform, livery or other "domestic workers' clothes" when in their employers' residence. The uniform is usually simple, though aristocratic employers sometimes provided elaborate decorative liveries, especially for use on formal occasions. Female servants wore long, plain, dark-coloured dresses or black skirts with white belts and white blouses, and black shoes, and male servants and butlers would wear something from a simple suit, or a white dress shirt, often with tie, and knickers. In traditional portrayals, the attire of domestic workers especially was typically more formal and conservative than that of those whom they serve. For example, in films of the early 20th century, a butler might appear in a tailcoat, while male family members and guests appeared in lounge suits or sports jackets and trousers depending on the occasion. In later portrayals, the employer and guests might wear casual slacks or even jeans, while a male domestic worker wore a jacket and tie or a white dress shirt with black trousers, necktie or bowtie, maybe even waistcoat, or a female domestic worker either a blouse and skirt (or trousers) or a uniform.

On 30 March 2009, Peru adopted a law banning employers from requiring domestic workers to wear uniform at public places. However, it's not explained which punishments will be given to employers violating the law.[5] Chile adopted a similar law in 2014, also banning employers to require domestic workers to wear uniform at public places.[6][7]

Current situation

ILO estimates in 2015 based on national surveys and/or censuses of 232 countries and territories, place the number of domestic workers at around 67.1 million.[8] But the ILO itself states that "experts say that due to the fact that this kind of work is often hidden and unregistered, the total number of domestic workers could be as high as 100 million".[9] The ILO also states that 83% of domestic workers are women and many are migrant workers.

In Guatemala, it is estimated that eight percent of all women work as domestic workers. They hardly have any legal protection. According to Guatemalan labour law, domestic work is "subject neither to a working time statute nor to regulations on the maximum number of working hours in a day". Legally, domestic helpers are only entitled to ten hours of free time in 24 hours, and one day off per week. But very often, these minimal employment laws are disregarded, and so are basic civil liberties.[10]

In Brazil, domestic workers must be hired under a registered contract and have many of the rights of any other workers, which includes a minimum wage, remunerated vacations and a remunerated weekly day off. It is not uncommon, however, for employers to hire servants illegally and fail to offer a work contract. Since domestic staff predominantly come from disadvantaged groups with less access to education, they are often vulnerable and uninformed of their rights, especially in rural areas. Nevertheless, domestics employed without a proper contract can successfully sue their employers and be compensated for abuse committed. It is common in Brazil for domestic staff, including childcare staff, to be required to wear uniforms, while this requirement has fallen out of use in other countries.

In the United States, domestic workers are generally excluded from many of the legal protections afforded to other classes of worker, including the provisions of the National Labor Relations Act.[11] Traditionally domestic workers have mostly been women and are likely to be immigrants.[12] New York has required mandatory overtime and breaks for domestic workers since 2010, though a California bill based on New York's, formerly known as AB 889, got through the legislature before being vetoed in September 2012 by Governor Jerry Brown.[13] America's domestic home help workers, most of them female members of minority groups, earn low wages and often receive no retirement or health benefits because the lack of basic labor protections. The report from the National Domestic Workers Alliance and affiliated groups found that nearly a quarter of nannies, caregivers, and home health workers make less than the minimum wage in the states in which they work, and nearly half – 48 percent – are paid less than needed to adequately support a family.[14]

Child domestic workers

The use of children as domestic servants continues to be common in parts of the world, such as Latin America and parts of Asia. Such children are very vulnerable to exploitation: often they are not allowed to take breaks or are required to work long hours; many suffer from a lack of access to education, which can contribute to social isolation and a lack of future opportunity. UNICEF considers domestic work to be among the lowest status, and reports that most child domestic workers are live-in workers and are under the round-the-clock control of their employers.[15] Some estimates suggest that among girls, domestic work is the most common form of employment.[16] Child domestic work is common in countries such as Bangladesh and Pakistan.[17][18] In Pakistan, since January 2010 to December 2013, 52 cases of tortures on child domestic workers are reported including 24 deaths.[19] It has been estimated that globally, at least 10 million children work in domestic labor jobs.[18]

Children face a number of risks that are common in domestic work service. The International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour identified that these risks include: long and tiring working days; use of toxic chemicals; carrying heavy loads; handling dangerous items such as knives, axes and hot pans; insufficient or inadequate food and accommodation, and humiliating or degrading treatment including physical and verbal violence, and sexual abuse.[20]

Domestic work and international migration

Many countries import domestic workers from abroad, usually from poorer countries, through recruitment agencies and brokers because their own nationals are no longer obliged or inclined to do domestic work, including in most Middle Eastern countries, Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia and Taiwan. There are at least one million domestic workers in Saudi Arabia under the kafala system.

Major sources of domestic workers include Thailand, Indonesia, India, the Philippines, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Ethiopia. Taiwan also imports domestic workers from Vietnam and Mongolia. Organizations such as Kalayaan support the growing number of these migrant domestic workers.

The migration of domestic workers can lead to several different effects both on the countries that are sending workers abroad and countries that are receiving domestic workers from abroad. One particular relationship between countries sending workers and countries receiving workers is that the sending country can be filling gaps in labor shortages of the receiving country.[21] This relationship can be potentially beneficial for both countries involved because the demand for labor is being met and fulfilled by workers' demand for jobs. This relationship however can prove to be quite complicated and not always beneficial. When unemployment in a receiving country rises migrant domestic workers are not only no longer needed but their presence can be detrimental to domestic workers of that country.[21]

When international migration began to flourish the assumed migrant worker was typically considered to be a man. What studies are now starting to show is that women are dominating large numbers of the international migration patterns by taking up large percentages of domestic workers that leave their home country in search for work as a domestic laborer in another country.[22]

Women who migrate to take up work as domestic workers are motivated by different reasons and migrate to a variety of different outcomes. While for many women, domestic work abroad is the only opportunity to find work and provide an income for their families, domestic labor is a market they are forced to enter due to blocked mobility in their homelands.[23] Additionally, migrant domestic workers often have to face the stress of leaving family members behind in their home countries while they take up work abroad. Upward mobility is particularly difficult for migrant domestic workers because their opportunities are often limited by their illegal status putting a very definite limitation on the work that is available to them as well as their power to negotiate with employers [24]

Advocacy of the debt owed to migrant domestic workers as a group

Some argue that personal sacrifices of domestic workers has helped to underpin economic and social development globally. Ariel Salleh's article "Ecological Debt: Embodied Debt", defines embodied debt as "debt owed by the Global North and Global South to the 'reproductive workers' who produce and maintain the new labour force."[25] According to the ILO, women constitute 80% of domestic workers.[26] The substantially high percentage of women in domestic work some argue results from this sector's association with motherhood, leading to an assumption that domestic work is by nature the work of females. In support, some argue that because domestic work occurs within the private sphere, which is seen as inherently feminine. This argument goes that the constructed link between domestic work and femininity [27] carries the implication that it is often referred to as 'domestic help,' and that domestic workers are referred to as 'nannies' or 'maids.' At least one author has argued that use of language compounded with the association with domestic work with femininities contributes to the exclusion of domestic work from the majority of national labour laws.[28]

Due to a lack of economic opportunity in the Global South, many women with families leave their countries of origin and their own families to pursue work in the Global North. When they arrive in their country of destination, their work often entails caring for another family (including children and the elderly). Domestic workers often migrate to financially support their immediate family, extended family, and even other members of their community. While enduring dangerous and demeaning working and living conditions in the North, the majority of their wages are remitted to their countries of origin.[29]

An additional argument has been made that because their work takes place within the private sphere, they are often rendered invisible and employers are able to withhold their travel documents, confining them to their employers' home and inhibiting their access to legal redress. Those making this argument assert that the result of what they refer to as a power dynamic and an asserted lack of labour rights, is that domestic workers are often forbidden to contact their families and often go months, years, and even decades without seeing their families, whose lives their remittances are supporting.

Further, it has been argued that their ability to fill labour shortages and accept positions within the reproductive labour force that citizens of their host countries would reject underpins the development of the global capitalist system,[30] Simultaneously, and that they are enabling the beneficiaries of their remittances in the South to ascend the social ladder. To some, these arguments lead to a conclusion that both circumstances in the North and South constitute embodied debt through the improvement of one's life at the expense of another's hardship, and that the labour of such workers is too often not seen as work, due to the association of their gendered bodies with reproductive labour.

However, on June 17, 2011, after 70 years of lobbying by civil society groups, the ILO adopted a convention with the aim of protecting and empowering domestic workers. Much of lobbying that contributed toward the ratification of ILO C189 was done by domestic workers groups, demonstrating that they are not merely victims but agents of change. That only two labour receiving countries have ratified the convention has been argued by some to demonstrates the reluctance of governments to acknowledge what such advocates see as a debt owed by society to such workers and to repay that perceived debt.[31]

Such advocates assert that the ratification and enforcement of ILO C189 would mean that migrant domestic workers would enjoy the same labour rights as other more 'masculine' fields as well as the citizens of their destination countries. An incomplete list of basic rights guaranteed by ILO C189 under Article 7 includes: maximum working hours; fixed minimum wages; paid leave; provision of food and accommodation; and weekly rest periods. Guaranteeing these rights to migrant domestic workers would not constitute repayment the embodied debt owed to them, but they are entitled to these rights as they are both workers and human beings.[32]

Social effects of domestic work

_lady.jpg)

As women currently dominate the domestic labor market throughout the world, they have learned to navigate the system of domestic work both in their own countries and abroad in order to maximize the benefits of entering the domestic labor market.

Among the disadvantages of working as a domestic worker is the fact that women working in this sector are working in an area often regarded as a private sphere.[33] Feminist critics of women working in the domestic sphere argue that this woman dominated market is reinforcing gender inequalities by potentially creating mistress-servant relationships between domestic workers and their employers and continuing to put women in a position of lesser power.[33] Other critics point out that working in a privatized sphere robs domestic workers of the advantages of more socialized work in the public sphere.[24]

Additionally, domestic laborers face other disadvantages. Their isolation is increased by their invisibility in the public sphere and the repetitive, intangible nature of their work decreases its value, making the workers themselves more dispensable.[34] The level of isolation women face also depends on the type of domestic work they are involved with. Live-in nannies for example may sacrifice much of their own independence and sometimes become increasingly isolated when they live with a family of which they are not part and away from their own.[35]

While working in a dominantly female privatized world can prove disadvantageous for domestic workers, many women have learned how to help one other move upward economically. Women find that informal networks of friends and families are among the most successful and commonly used means of finding and securing jobs.[36]

Without the security of legal protection, many women who work without the requisite identity or citizenship papers are vulnerable to abuse. Some have to perform tasks considered degrading showing a manifestation of employer power over worker powerlessness. Employing domestic work from foreign countries can perpetuate the idea that domestic or service work is reserved for other social or racial groups and plays into the stereotype that it is work for inferior groups of people.[37]

Gaining employment in the domestic labor market can prove to be difficult for immigrant women. Many subcontract their services to more established women workers, creating an important apprenticeship type of learning experience that can produce better, more independent opportunities in the future.[24] Women who work as domestic workers also gain some employment mobility. Once established they have the option of accepting jobs from multiple employers increasing their income and their experience and most importantly their ability to negotiate prices with their employers.[34]

Trends in domestic work

The domestic work industry is currently dominated throughout the world by women.[38]

While the domestic work industry is advantageous for women in that it provides them a sector that they have substantial access to, it can also prove to be disadvantageous by reinforcing gender inequality through the idea that domestic work is an industry that should be dominated by women. Within the domestic work industry the much smaller proportion of jobs that is occupied by men are not the same jobs that are typically occupied by women. Within the child care industry men make up only about 3–6% of all workers.[39] Additionally, in the child care industry men are more likely to fill roles that are not domestic in nature but administrative such as a managerial role in a day care center.[40]

While the domestic work industry was once believed to be an industry that belonged to a past type of society and did not belong in a modern world, trends are showing that although elements of the domestic work industry have been changing the industry itself has shown no signs of fading away, but only signs of transformation.[39] There are several specific causes that are credited to continuing the cycle of the demand for domestic work. One of these causes is that with more women taking up full-time jobs, a dually employed household with children places a heavy burden on parents. It is argued however that this burden wouldn't result in the demand for outside domestic help if men and women were providing equal levels of effort in domestic work and child rearing within their own home.[33]

The demand for domestic workers has also become largely fulfilled by migrant domestic workers from other countries who flock to wealthier nations to fulfill the demand for help at home.[38][41] This trend of domestic workers flowing from poorer nations to richer nations creates a relationship that on some levels encourages the liberation of one group of people at the expense of the exploitation of another.[38] Although domestic work has far from begun to fade from society, the demand for it and the people who fill that demand has changed drastically over time.

Varieties of domestic work

- Au pair - A foreign-national domestic assistant working for, and living as part of, a host family.

- Amanuensis - A person employed to write or type what another dictates or to copy what has been written by another

- Ayah - A job that is similar to a nanny.

- Babysitter - A worker who watches the children of someone.

- Bedder - A worker who makes the beds.

- Between maid - An in-between maid whose duties are half in the reception rooms and half in the kitchen.

- Bodyguard - A worker who protects his employer.

- Boot boy - A young male servant, employed mostly to perform footwear maintenance and minor auxiliary tasks.

- Butler - A senior employee usually found in larger households, almost invariably a man, whose duties traditionally include overseeing the wine cellar, the silverware, and some oversight of the other, usually male, servants.

- Castellan - A castle official.

- Chambermaid - a maid whose chief focus is on cleaning and maintaining bedrooms, ensuring fires are lit in fireplaces, and supplying hot water.

- Charwoman (AKA Char) - A female house or office cleaner, usually part-time.

- Chauffeur - A personal driver.

- Cleaner - A worker who cleans homes or commercial premises.

- Cook - Either a cook who works alone or the head of a team of cooks that work for their employer.

- Dog walker - A worker who walks the dog.

- Footman - Lower-ranking domestic worker.

- Gardener - A worker who tends to the garden.

- Governess - A woman teacher for children.

- Groundskeeper - a worker who tends to the person's large property.

- Hall boy - The lowest ranking male servant that is usually found only in large households

- Handyman - A worker who handles household repairs.

- Horse trainer - A worker who trains their boss' horses.

- Houseboy - A worker who does personal chores.

- Housekeeper - This job usually describes a female senior employee.

- Kitchen maid - A worker who works for the cook.

- Lackey - A runner that is usually overworked and underpaid.

- Lady's maid, - A woman's personal attendant, helping her with her clothes, shoes, accessories, hair, and cosmetics.

- Laundress - A laundry servant.

- Maid (AKA Housemaid) - Female servants who do the typical duties.

- Majordomo - The senior most staff member of a very large household or stately home. See also Seneschal.

- Masseur/Masseuse - A servant who handles the massages.

- Nanny (AKA nurse) - A woman taking care of infants and children.

- Nursemaid (AKA Nursery Maid) - A maid who handles the nursery.

- Personal shopper - A worker who does all the shopping.

- Personal trainer - A worker that trains their employer in fitness, swimming, and sports.

- Pool person - A worker who works by the swimming pool.

- Retainer - A servant, especially one who has been with one family for a long time (chiefly British English).[42]

- Scullery maid - The lowest-ranking and youngest of the domestic workers that act as the assistants to the kitchen maid.

- Stable boy - A worker who handles the management of the horses and the stables

- Valet - Also known as the "gentleman's gentleman", the valets are responsible for the master's wardrobe and assisting him in dressing, etc. In the armed forces some officers have a soldier (in the British army called a batman) for such duties

- Wet nurse - A nurse who provides suckling for infants if mothers cannot or do not wish to do so themselves.

Notable domestic workers

- Abdul Karim (the Munshi), servant of Queen Victoria of Great Britain

- Céleste Albaret, housekeeper of Marcel Proust

- Gladys Aylward, maid, afterwards missionary

- Alice Ayres, nursemaid honoured for her bravery in rescuing the children in her care from a house fire

- Sarah Balabagan

- Fonzworth Bentley

- Emily Blatchley, governess and missionary

- Sophie Brzeska, governess and writer

- Paul Burrell, butler to Diana, Princess of Wales

- Elizabeth Canning, maidservant in London

- Princess Caraboo (Mary Baker), English imposter

- Flor Contemplacion, murderer

- Elizabeth Cotten, musician, working for Charles Seeger the ethnomusicologist

- Hannah Cullwick, maid to A. J. Munby

- Lisette Denison Forth, maid and philanthropist

- Alonzo Fields, butler at the White House

- Caroline Herschel, astronomer (worked as a domestic servant in her father's household until his death)

- Paul Hogan

- Bridget Holmes, chambermaid to kings of England

- Hélène Jégado, serial killer

- Dora Lee Jones, trade unionist

- Anna Leonowens, governess to the children of the King of Siam

- Thérèse Levasseur, laundress and chambermaid

- Margaret Maher, maid to Emily Dickinson

- Notburga, German saint, patron of hired hands

- Papin sisters, murderers

- Lillian Rogers Parks, housemaid and seamstress in the White House

- Rose Porteous

- Margaret Powell, maid and writer

- Casimira Rodríguez

- Margaret Rogers

- Charles Spence, Scottish poet, stonemason and footman

- Deb Willet, maid in the household of Samuel Pepys

Cultural depictions

Domestic workers in religion

- Saint Zita, the patron saint of domestic servants

- Category:Canonised servants of the Romanov household

Domestic workers in fiction

- A Little Princess, a book made into several films

- Amelia Bedelia, children's comedy fiction

- Beryl's Lot, a British television series based on Margaret Powell's memoirs of domestic service

- Cinderella, a fairytale, cartoon and film

- Downton Abbey, a British television series set in a large English country house

- Gone with the Wind, a Pulitzer Prize-winning American novel and Academy Award-winning film

- The Diary of a Chambermaid, a novel by Octave Mirbeau

- The Remains of the Day, Man Booker Prize–winning novel

- Upstairs, Downstairs, a British television series set in London

- Upstairs Downstairs (remake), a British television series set in London

- You Rang, M'Lord?, a British television comedy series

- The Help, a novel by Kathryn Stockett

- Alfred Pennyworth, Bruce Wayne’s faithful butler, created by Bob Kane and Bill Finger

Domestic workers in visual art

The Chocolate Girl, by Jean-Étienne Liotard (c. 1734–1744)

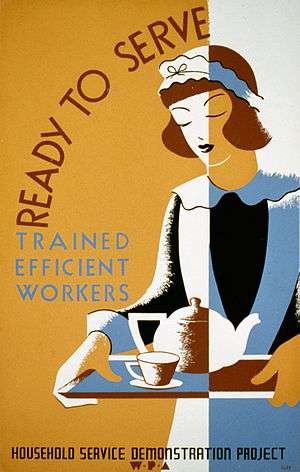

The Chocolate Girl, by Jean-Étienne Liotard (c. 1734–1744) A poster of an American maid in uniform (ca. 1939)

A poster of an American maid in uniform (ca. 1939) Young water carrier drawing by Heinrich Zille (by 1929)

Young water carrier drawing by Heinrich Zille (by 1929) Colonial dining, William Henry Jackson (1895)

Colonial dining, William Henry Jackson (1895)

See also

References

- ↑ Anti-Slavery International. "Domestic Work and Slavery". Anti-Slavery.Org. Anti-Slavery International. Archived from the original on 30 September 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ↑ "Resource guide on domestic workers". International Labour Organization. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ↑ "Uruguay First Country to Ratify C189". Idwn.info. 2012-05-03. Archived from the original on 2012-10-25. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

- ↑ "Domestice Worker Chart". ThinkProgress. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ↑ Isabel Guerra (30 March 2009). "Peru: Domestic servants can no longer be forced to wear uniforms in public". Living in Peru. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ↑ "Housemaid-turned-rapper gives voice to suffering of domestic helpers in Latin America". South China Morning Post. 4 August 2016. Archived from the original on 19 January 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ↑ "Brazil rapper voices Latin housemaids' suffering". New Strait Times. 4 August 2016. Archived from the original on 19 January 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ↑ "ILO Global estimates of migrant workers and migrant domestic workers: results and methodology" (PDF). International Labour Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-03-29. Retrieved 2016-12-23.

- ↑ "100th ILO annual Conference decides to bring an estimated 53 to 100 million domestic workers worldwide under the realm of labour standards". International Labour Organization. Archived from the original on 2016-12-27. Retrieved 2016-12-23.

- ↑ Verfürth, Eva-Maria (n.d.). "Hard work new opportunities". D+C Development and Cooperation No. 09 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-10-12. Retrieved 2009-01-10.

- ↑ See the UN Human Rights Committee's report, "Domestic Workers' Rights in the United States."

- ↑ Graff, Daniel A. (n.d.). "Domestic Work and Workers". The Electronic Encyclopedia of Chicago. Archived from the original on 2009-05-13. Retrieved 2009-08-31.

- ↑ Bello, Grace (January 17, 2013). "The Home Economics of Domestic Workers". Archived from the original on January 31, 2013.

- ↑ "Without Labor Protections, Domestic Workers Earn Low Wages And Receive No Benefits". Archived from the original on 2013-10-04.

- ↑ "Counting Cinderellas Child Domestic Servants – Numbers and Trends". Archived from the original on 2011-08-23.

- ↑ "Child domestic workers: Finding a voice" (PDF). Antislavery.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 3, 2013. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-18. Retrieved 2011-05-02.

- 1 2 Archived April 10, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "The ISJ demands immediate ban on child domestic labour in Pakistan | The Institute for Social Justice". ISJ. 2014-01-07. Archived from the original on 2014-01-11. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ↑ "Ending child labour in domestic work and protecting young workers from abusive working conditions".

- 1 2 "Who needs migrant workers? Introduction to the analysis of staff shortages, immigration and public policy". Bridget Anderson and Martin Ruhs, Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS) University of Oxford Working draft: 11th May 2009

- ↑ WOMEN AND MIGRATION: The Social Consequences of Gender, Silvia Pedraza, Department of Sociology and Program in American Culture, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION, DOMESTIC WORK, AND CARE WORK Undocumented Latina Migrants in Israel, Rebeca Raijman, University of Haifa, Israel, SILVINA SCHAMMAH-GESSER and ADRIANA KEMP, Tel Aviv University

- 1 2 3 "Ways to Come, Ways to Leave: Gender, Mobility, and Il/legality among Ethiopian Domestic Workers in Yemen", Gender & Society; 2010 24: 237, Marina De Regt

- ↑ Ariel Salleh, ed. "Ecological Debt: Embodied Debt," in Eco-Sufficiency and Global Justice (Pluto Press: London, 2009) 5.

- ↑ Mark Tran. "ILO urges better pay and conditions for 53 million domestic workers | Global development". theguardian.com. Archived from the original on 2014-10-29. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ↑ Jindy Pettman. "Migration," in Gender Matters in Global Politics ed. Laura Shepherd (Routlege, New York: 2010) 257.

- ↑ Salleh, "Ecological Debt: Embodied Debt," 3.

- ↑ Jindy Pettman, "Migration," in Gender Matters in Global Politics ed. Laura Shepherd (Routlege, New York: 2010) 257.

- ↑ Pettman, Jindy, "Migration," 257.

- ↑ "Ratify and Implement ILO Convention 189 on Decent Work for Domestic Workers Now!". Mfasia.org. 2012-06-16. Archived from the original on 2013-12-12. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ↑ "Convention C189 - Domestic Workers Convention, 2011 (No. 189)". www.ilo.org. Archived from the original on 3 November 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 Arat-Koc, S. (1992) 'In the Privacy of Our Own Home: Foreign Domestic Workers as a Solution to the Crisis of the domestic sphere in Canada', P. Connelly and P. Armstrong (eds) Feminism in Action: Studies in Political Economy, Toronto: Canadian Studies Press.

- 1 2 Regulating the Unregulated?: Domestic Workers' Social Networks, Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo, Social Problems, Vol. 41, No. 1, Special Issue on Immigration, Race, and Ethnicity in America (Feb., 1994), pp. 50–64

- ↑ Pratt, Geraldine. "From Registered Nurse to Registered Nanny: Discursive Geographies of Filipina Domestic Workers in Vancouver, BC*." Economic Geography 75.3 (1999): 215–236.

- ↑ Andall, Jacqueline. "Organizing domestic workers in Italy: the challenge of gender, class and ethnicity." Gender and Migration in Southern Europe (2000): 145–171.

- ↑ Just Another Job? Paying for Domestic Work, Bridget Anderson Gender and Development, Vol. 9, No. 1, Money (Mar., 2001), pp. 25–33

- 1 2 3 "Feminists and Domestic Workers; Muchachas No More: Domestic Workers in Latin America and the Caribbean" by Elsa M. Chaney; Mary Garcia Castro

- 1 2 Susan B. Murray, "'We all love Charles': men in child care and the social construction of gender", Gender & Society; (1996) 10: 368

- ↑ Silvey, R. (2004), "Transnational Migration and the Gender Politics of Scale: Indonesian Domestic Workers in Saudi Arabia". Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography

- ↑ Domesticity and Dirt: Housewives and Domestic Servants in the United States, 1920–1989; by Phyllis Palmer

- ↑ "Definition of 'retainer'". Collins English Dictionary - collinsdictionary.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

Further reading

- The Duties of Servants; by a member of the aristocracy, author of 'Manners and Rules of Good Society'. London: F. Warne & Co., 1894

- A Few Rules for the Manners of Servants in Good Families. Ladies' Sanitary Association, 1901

- The Servants' Practical Guide: a handbook of duties and rules; by the author of 'Manners and Tone of Good Society'. London: Frederick Warne & Co., [1880]

- The Management of Servants: a practical guide to the routine of domestic service; by the author of "Manners and Tone of Good Society." (the same work under a different title)

- Dawes, Frank (1973) Not in Front of the Servants: domestic service in England 1850–1939. London: Wayland ISBN 0-85340-287-6

- Evans, Siân (2011) Life below Stairs in the Victorian and Edwardian Country House. National Trust Books

- --do.--"Yells, Bells and Smells ... from royal visits ... to the case of the cook and the freezer", in: National Trust Magazine; Autumn 2011, pp. 70–73

- Musson, Jeremy (2009) Up and Down Stairs: the history of the country house servant. London: John Murray ISBN 978-0-7195-9730-5

External links

| Look up domestic worker in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Domestic workers. |

- International Domestic Workers Network

- List of digitized books on domestic workers in German, English, and other languages at de.wikisource

- ILO resources on domestic workers:

- Amnesty International paper on the abuse of domestic workers in the Middle East

- A Global Justice Center paper about domestic workers worldwide

- An international campaign for domestic workers' labour rights

- A Research Project entitled "Servants Pasts" which traces domestic service historically

- Human Rights Watch article about migrant domestic workers

- Interview with an Indonesian domestic worker in Singapore Clip from documentary film 'At Your Service' (2010, director Jorge Leon)