Rembert Dodoens

| Rembert Dodoens | |

|---|---|

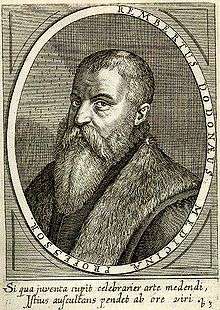

Rembert Dodoens, by Theodor de Bry, in Bibliotheca chalcographica (1669) | |

| Born |

29 June 1517 Mechelen |

| Died |

10 March 1585 (aged 67) Leiden |

| Resting place | Pieterskerk, Leiden |

| Nationality | Flemish |

| Alma mater | University of Leuven |

| Known for | Herbal |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 5 |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Medicine, botany |

| Institutions | Mechelin, Vienna, Leiden University |

| Influences | Otto Brunfels, Jerome Bock, Leonhard Fuchs |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Dodoens |

Rembert Dodoens (born Rembert Van Joenckema, 29 June 1517 – 10 March 1585) was a Flemish physician and botanist, also known under his Latinized name Rembertus Dodonaeus.

Life

Dodoens was born Rembert van Joenckema in Mechelen, a town between Antwerp and Brussels and capital of the Spanish Netherlands, in 1517 to Denis Van Joenckema (d. 1533) and Ursula Roelants. The van Joenckema family and name were Frisian in origin. In Friesland they were active in politics and jurisprudence, and in 1516 moved to Mechelen.[1] His father was one of the municipal physicians in Mechelen and had been one of the private physicians to Margaret of Austria, Governor of the Netherlands, in her final illness, whose court was based in Mechelen.[2] Rembert later changed his last name to Dodoens (literally "Son of Dodo", a form of his father's name, Denis or Doede).

He was educated at the municipal college in Mechelen before beginning his studies in medicine, cosmography and geography at the age of 13 at the University of Leuven (Louvain), under Arnold Noot, Leonard Willemaer, Jean Heems, and Paul Roelswhere. He graduated with a licentiate in medicine in 1535, and as was the custom of the time, began extensive travels (Wanderjahren) in Europe till 1546, including Italy, Germany, and France. In 1539 he married Kathelijne De Bruyn (1517–1572), who came from a medical family in Mechelen. With her he had four children, Ursula (b. 1544), Denijs (b. 1548), Antonia and Rembert Dodoens.[3] He had a short stay in Basel (1542–1546). In 1557, Dodoens turned down a chair at the University of Leuven. He also turned down an offer to become court physician of king Philip II of Spain. After his wife's death at the age of 55 in 1572, he married Maria Saerinen by whom he had a daughter, Johanna.[4] He died in Leiden in 1585, and was buried at Pieterskerk, Leiden.[5][6][1]

Work

After graduation, he eventually established himself as one of the three municipal physicians in Mechelen, as his father had been, together with Joachim Roelandts and Jacob De Moor, in 1548.[1][7] He became the court physician of the Holy Roman emperor Maximilian II, and his successor, Austrian emperor Rudolph II in Vienna (1575–1578). In 1582, he finally became professor in medicine at the University of Leiden in 1582.[5]

Life and times

At the opening of the sixteenth century the general belief was that the plant world had been completely described by Dioscorides, in his De Materia Medica. During Dodoens' lifetime, botanical knowledge was undergoing enormous expansion, partly fueled by the expansion of the known plant world by New World exploration, the discovery of printing and the use of wood-block illustration. This period is thought of as a botanical Renaissance. Europe became engrossed with natural history from the 1530s, and gardening and cultivation of plants became a passion and prestigious pursuit from monarchs to universities. The first botanical gardens appeared as well as the first illustrated botanical encyclopaedias, together with thousands of watercolours and woodcuts. The experience of farmers, gardeners, foresters, apothecaries and physicians was being supplemented by the rise of the plant expert. Collecting became a discipline, specifically the Kunst- und Wunderkammern (cabinets of curiosities) outside of Italy and the study of naturalia became widespread through many social strata. The great botanists of the sixteenth century were all, like Dodoens, originally trained as physicians, who pursued a knowledge of plants not just for medicinal properties, but in their own right. Chairs in botany, within medical faculties were being established in European universities throughout the sixteenth century in reaction to this trend, and the scientific approach of observation, documentation and experimentation was being applied to the study of plants.[8]

Otto Brunfels published his Herbarium in 1530, followed by those of Jerome Bock (1539) and Leonhard Fuchs (1542), men that Kurt Sprengel would later call the “German fathers of botany”. These men all influenced Dodoens, who was their successor.[8]

Publications

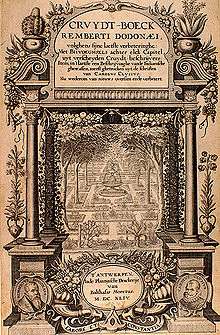

Dodoens' initial work was in the fields of cosmography and physiology. His De frugum historia (1552), a treatise on cereals, vegetables, and fodders [9] marked the beginning of a distinguished career in botany, and his herbal Cruydeboeck (herb book) with 715 images (1554, 1563)[10] was influenced by earlier German botanists, particularly that of Leonhart Fuchs. Rather than the traditional method of arranging the plants in alphabetical order, he divided the plant kingdom into six groups (Deel), based on their properties and affinities. It treated in detail especially the medicinal herbs, which made this work, in the eyes of many, a pharmacopoeia. This work and its various editions and translations became one of the most important botanical works of the late 16th century, part of its popularity being his use of the vernacular rather than the commonly used Latin.[1][5]

Cruydeboeck was translated first into French in 1557 by Charles de L'Ecluse (Histoire des Plantes),[11] and into English (via L'Ecluse) in 1578 by Henry Lyte (A new herbal, or historie of plants), and later into Latin in 1583 (Stirpium historiae pemptades sex).[12] The English version became a standard work in that language. In his times, it was the most translated book after the Bible. It became a work of worldwide renown, used as a reference book for two centuries.[lower-alpha 1][13]

His Latin translation of 1583, the Stirpium or Pemtdades, was also a considerable revision, adding new families, enlarging the number of groups from 6 to 26 and including many new illustrations, both original and borrowed. It was used by John Gerard as the source for his widely used Herball (1597).[14][5] Thomas Johnson, in his preface to his 1633 edition of Herball, explains the controversial use of Dodoens' work by Gerard.[lower-alpha 2][14]

List of selected publications

- Dodoens, Rembert (1533). Herbarium.

- — (1543). Den Nieuwen Herbarius.

- — (1548). Cosmographica in astronomiam et geographiam isagoge.

- (1584) De sphaera sive de astronomiae et geographiae principiis cosmographica isagoge. Antwerp (2nd ed.)

- Dodoens, Rembert (1552). De frugum historia, liber unus. Ejusdem epistolae duae, una de Fare, Chondro, Trago, Ptisana, Crimno et Alica; altera de Zytho et Cerevisia. Antwerp.

- Dodoens, Rembert (1554). Trium priorum de stirpium historia commentariorum imagines.

- Dodoens, Rembert (1554). Posteriorum trium de stirpium historia commentariorum imagines.

- Dodoens, Rembert (1554). Des Cruydboeks (in Dutch and Latin) (1st ed.). Antwerp: J. van der Loe. , also at Teylers Museum

- Dodoens, Rembert (1566). Historia frumentorum, leguminum, palustrium et aquatilium herbarum acceorum, quae eo pertinent. [lower-alpha 4]

- Dodoens, Rembert (1574). Purgantium aliarumque eo facientium, tam et radicum, convolvulorum ac deletariarum herbarum historiae libri IIII.... Accessit appendix variarum et quidem rarissimarum nonnullarum stirpium, ac florum quorumdam peregrinorum elegantissimorumque icones omnino novas nec antea editas, singulorumque breves descriptiones continens... [On purgatives] (in Latin). Antwerp: Christophe Plantin. 2nd ed. 1576, see also Aboca Museum

- Dodoens, Rembert (1550). Physiologices medicinae tabulae.

- Dodoens, Rembert (1581). Medicinalium observationum exempla rara.

- — (1583) [1554]. Stirpium historiae pemptades sex, sive libri XXX [Crvyd-boeck] (in Latin). Antwerp: Plantini.

Posthumous

- Praxis medica (1616)

- Remberti Dodonaei Mechilensis ... stirpium historiae pemptades sex, sive libri XXX : varie ab Auctore, paullo ante Mortem, aucti & emendati. Antverpiae : Moretus / Plantin, 1616 Digital edition of the University and State Library Düsseldorf.

- Ars medica, ofte ghenees-kunst (1624)

- Cruydt-Boeck (1644) (13th, last and most comprehensive edition, 5th Flemish ed.)

Works in translation

- Dodoens, Rembert (1557) [1554]. Cruydeboeck [Histoire des plantes] (in French). trans. from Dutch, by Carolus Clusius. Antwerp: de l'Imprimerie de Iean Loë. [lower-alpha 5]

- Dodoens, Rembert (1619). Cruijdeboeck [A new herbal, or historie of plants]. trans. from French (Histoire des plantes 1557) and Flemish (1563) by Henry Lyte.

Legacy

Dodoens has been called the father of botany.[lower-alpha 6] Dodoens life and work is commemorated by this statue, in the Kruidentuin (botanical garden) in Mechelen. There is also a commemorative plaque at St Peter's church, Leiden, where he is buried.

Eponomy

The plant genus Dodonaea was named after Dodoens, by Carl Linnaeus. The following species are also named after him: Epilobium dodonaei,: Comocladia dodonaea, Phellandrium dodonaei, Smyrnium dodonaei, Hypericum dodonaei and Pelargonium dodonaei .

Notes

- ↑ Het Cruijdeboeck, dat in 1554 verscheen. Dit meesterwerk was na de bijbel in die tijd het meest vertaalde boek. Het werd gedurende meer dan een eeuw steeds weer heruitgegeven en gedurende meer dan twee eeuwen was het het meest gebruikte handboek over kruiden in West-Europa. Het is een werk van wereldfaam en grote wetenschappelijke waarde. De nieuwe gedachten die Dodoens erin neerlegde, werden de bouwstenen voor de botanici en medici van latere generaties. (The Cruijdeboeck, published in 1554. This masterpiece was, after the bible, the most translated book in that time. It continued to be republished for more than a century and for more than two centuries it was the mostly used referential about herbs. It is a work with world fame and great scientific value. The new thoughts written down by Dodoens, became the building bricks for botanists and physicians of later generations)[13]

- ↑ Rembertus Dodoneus a Physition borne at Mechlin in Brabant, about this time begun to write of Plants. Hee first set foorth a Historie in Dutch, which by Clusius was turned into French, with some additions, Anno Domini 1560. And this was translated out of French into English by Master Henry Lite, and set forth with figures, Anno Dom. 1578 and diuers times since printed, but without Figures… Afterwards hee put them all together, his former, and those his later Workes, and diuided into thirtie Bookes, and set them forth with 1305 figures, in fol. An. 1583. This edition was also translated into English.[14]

- ↑ Cruydeboek: Illustrations by Pieter van der Borcht[15]

- ↑ Historia frumentorum: Pieter van der Borcht made 60 drawings of plants for this herbarium that was published by Christopher Plantin in Antwerp[15]

- ↑ Histoire des plantes ran to 27 editions[16]

- ↑ "Dodoens qui est incontestablement le père de la botanique"[16]

References

Bibliography

Books and articles

- Cock, Alfons De (1890). Rembert Dodoens (in Dutch). Vuylsteke.

- Mortier, Barthélemy-Charles Du (1873). Opuscules de botanique 1862-1873. Brussels: G. Mayolez. p. vi.

- Gerard, John (2015) [1633]. Johnson, Thomas, ed. The Herbal Or General History of Plants. Originally published by Adam Islip, Joice Norton and Richard Whitakers in London (2nd ed.). NY: Dover. ISBN 9781606600801.

- Guy Gilias; Cornelis van Tilburg; Vincent Van Roy, eds. (2016). Rembert Dodoens: Een zestiende-eeuwse kruidenwetenschapper, zijn tijd- en vakgenoten en zijn betekenis (in Dutch). Maklu. ISBN 978-90-441-3530-5.

- Pascale Pollier-Green; Ann van de Velde; Chantal Pollier, eds. (2007). Confronting Mortality with Art and Science: Scientific and Artistic Impressions on what the Certainty of Death Says about Life. Asp / Vubpress / Upa. ISBN 978-90-5487-443-0.

- Pavord, Anna (2005). The naming of names the search for order in the world of plants. New York: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781596919655.

- Sachs, Julius von (1890) [1875]. "The Botanists of Germany and the Netherlands from Brunfels to Kaspar Bauhin. 1530–1623". Geschichte der Botanik vom 16. Jahrhundert bis 1860 [History of botany (1530-1860)]. translated by Henry E. F. Garnsey, revised by Isaac Bayley Balfour. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 13–36. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.30585.

- Stafleu, Frans A.; Cowan, Richard S. (1976). "Dodoens, Rembert". Taxonomic literature: a selective guide to botanical publications and collections with dates, commentaries and types. Volume 1. A–G (2nd ed.). Utrecht: Bohn, Scheltema & Holkema. pp. 661–665.

- Vande Walle, W.F., ed. (2001). Dodonæus in Japan: translation and the scientific mind in the Tokugawa period. Leuven: Leuven University Press. ISBN 9789058671790.

- Florkin, Marcel (2008). Dodoens (Dodonaeus), Rembert. Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- Brown, Mark (19 May 2015). "Shakespeare: writer claims discovery of only portrait made during his lifetime". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- Griffiths, Mark (25 August 2015). "The true face of Shakespeare: Dioscorides and the Fourth Man". Country Life. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

Chapters

- Huskin, Wim. Rembert Dodoens: Forensc Medicine in 16th-century Mechelen. pp. 104–111. , in Pollier-Green et al (2007)

- van Hee, Bob. Rembert Dodoens en zijn Galenisch therapeutisch denkbeeld. pp. 33–44. , in Gilias et al (2016)

- Vande Walle, W. F. Dodonaeus: A bio-bibliographical summary. pp. 33–43. , in Vande Walle (2001)

- Visseer, Robert. Dodonaeus and the herbal tradition. pp. 44–58. , in Vande Walle (2001)

Websites

- "Rembert Dodoens: iets over zijn leven en werk – Dodoens' werken". Plantaardigheden – Project Rembert Dodoens (Rembertus Dodonaeus) (in Dutch). Stichting Kruidenhoeve/Plantaardigheden, Balkbrug, Netherlands. 20 December 2005. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- Badke, David (1 September 2004). "Pieter van der Borcht". Sancti Ephiphani ad Physiologum. University of Victoria. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- Luebering, J.E. (9 December 2008). "Rembert Dodoens". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- "Rembert Dodoens". Botany at the Edward Worth Library. Dublin: Edward Worth Library, Dr Steevens' Hospital. 2017. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- "Dodoens, Rembert, 1517-1585". Biodiversity Heritage Library. Retrieved 4 November 2017. Bibliography

- Homs, George J. (9 March 2015). "Rembertus Dodonaeus". Geni. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- van Riemsdijk, Willem; van Riemsdijk-Zandee, Trudy. "Christine Bertolf en Dodonaeus Netwerken in de zestiende eeuw". Stinze Stiens (in Dutch). Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- Westfall, Richard S. (1995). "Dodoens, Rembert". The Galileo Project. Rice University. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

External links

- Extensive link collection of old herbals on the internet - commentary in Dutch.

- Online Galleries, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries High resolution images of works by and/or portraits of Rembert Dodoens in .jpg and .tiff format.

- Environmental History of the Rhine Meuse Delta

- Information on the Kruidtuin

- Photographs of the Kruidentuin

- Memorial at St Peter's

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rembert Dodoens. |