Distributed version control

In software development, distributed version control (also known as distributed revision control) is a form of version control where the complete codebase - including its full history - is mirrored on every developer's computer.[1] This allows branching and merging to be managed automatically, increases speeds of most operations (except for pushing and pulling), improves the ability to work offline, and does not rely on a single location for backups.[1][2][3][4]

Software development author Joel Spolsky, described DVCS as "possibly the biggest advance in software development technology in the [past] ten years."[5]

Distributed vs. centralized

Distributed revision control systems (DVCS) takes a peer-to-peer approach to version control, as opposed to the client–server approach of centralized systems. Distributed revision control synchronizes repositories by exchanging patches from peer to peer. There is no single central version of the codebase; instead, each user has a working copy and the full change history.

Advantages of DVCS (compared with centralized systems) include:

- Allows users to work productively when not connected to a network.

- Common operations (such as commits, viewing history, and reverting changes) are faster for DVCS, because there is no need to communicate with a central server.[6] With DVCS, communication is only necessary when sharing changes among other peers.

- Allows private work, so users can use their changes even for early drafts they do not want to publish.

- Working copies effectively function as remote backups, which avoids relying on one physical machine as a single point of failure.[6]

- Allows various development models to be used, such as using development branches or a Commander/Lieutenant model.

- Permits centralized control of the "release version" of the project

- On FOSS software projects it is much easier to create a project fork from a project that is stalled because of leadership conflicts or design disagreements.

Disadvantages of DVCS (compared with centralized systems) include:

- Initial checkout of a repository is slower as compared to checkout in a centralized version control system, because all branches and revision history are copied to the local machine by default.

- The lack of locking mechanisms that is part of most centralized VCS and still plays an important role when it comes to non-mergeable binary files such as graphic assets.

- Additional storage required for every user to have a complete copy of the complete codebase history.[7]

Some originally centralized systems now offer some distributed features. For example, Subversion is able to do many operations with no network.[8] Team Foundation Server and Visual Studio Team Services now host centralized and distributed version control repositories via hosting Git.

Work model

The distributed model is generally better suited for large projects with partly independent developers, such as the Linux kernel project, because developers can work independently and submit their changes for merge (or rejection). The distributed model flexibly allows adopting custom source code contribution workflows. The integrator workflow is the most widely used. In the centralized model, developers must serialize their work, to avoid problems with different versions.

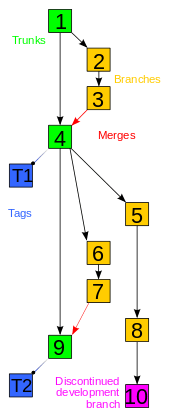

Central and branch repositories

Every project has a central repository that is considered as the official repository, which is managed by the project maintainers. Developers clone this repository to create identical local copies of the code base. Source code changes in the central repository are periodically synchronized with the local repository.

The developer creates a new branch in his local repository and modifies source code on that branch. Once the development is done, the change needs to be integrated into the central repository.

Pull requests

Contributions to a source code repository that uses a distributed version control system are commonly made by means of a pull request, also known as a merge request.[9] The contributor requests that the project maintainer pull the source code change, hence the name "pull request". The maintainer has to merge the pull request if the contribution should become part of the source base.[10]

The developer creates a pull request to notify maintainers of a new change; a comment thread is associated with each pull request. This allows for focused discussion of code changes. Submitted pull requests are visible to anyone with repository access. A pull request can be accepted or rejected by maintainers.[11]

Once the pull request is reviewed and approved, it is merged into the repository. Depending on the established workflow, the code may need to be tested before being included into official release. Therefore, some projects contain a special branch for merging untested pull requests.[10][12] Other projects run an automated test suite on every pull request, using a continuous integration tool such as Travis CI, and the reviewer checks that any new code has appropriate test coverage.

History

BitKeeper was used in the development of the Linux kernel from 2002 to 2005.[13] The development of Git, now the world's most popular version control system,[14] was prompted by the decision of the company that made BitKeeper to rescind the free license that Linus Torvalds and some other Linux kernel developers had previously taken advantage of.[13]

Prior to Git, the first open-source DVCS systems included Arch, Monotone, and Darcs. However, open source DVCSs were never very popular until the release of Git and Mercurial.

See also

- Version control

- List of version control software

- Comparison of version control software

- Category:Software using distributed version control

- Repository clone

- Git, an open source DVCS developed for Linux Kernel development

- Mercurial, a cross-platform system similar to Git

- Fossil, a distributed version control system, bug tracking system and wiki software

- BitKeeper

- GNU Bazaar

- Concurrent Versions System, a predecessor of distributed version control systems

- TortoiseHg, a graphical interface for Mercurial

- Code Co-op, a peer-to-peer version control system

References

- 1 2 "GIT - About Version Control". www.git-scm.com. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ↑ "Distributed Version Control is here to stay, baby". www.joelonsoftware.com. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ↑ "Intro to Distributed Version Control (Illustrated)". www.betterexplained.com. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ↑ "What Is Git ? – Explore A Distributed Version Control Tool". www.edureka.co. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ↑ Spolsky, Joel (2010-03-17). "Distributed Version Control is here to stay, baby". Joel on Software. Retrieved 2010-06-18.

- 1 2 O'Sullivan, Bryan. "Distributed revision control with Mercurial". Retrieved July 13, 2007.

- ↑ "What is version control: centralized vs. DVCS". www.atlassian.com. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ↑ OSDir.com. "Subversion for CVS Users :: OSDir.com :: Open Source, Linux News & Software". OSDir.com. Retrieved 2013-07-22.

- ↑ Sijbrandij, Sytse (29 September 2014). "GitLab Flow". GitLab. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- 1 2 Johnson, Mark (8 November 2013). "What is a pull request?". Oaawatch. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ↑ "Using pull requests". GitHub. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ↑ "Making a Pull Request". Atlassian. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- 1 2 McAllister, Neil. "Linus Torvalds' BitKeeper blunder". InfoWorld. Retrieved 2017-03-19.

- ↑ "Version Control Systems Popularity in 2016". www.rhodecode.com. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

External links

- Essay on various revision control systems, especially the section "Centralized vs. Decentralized SCM"

- Introduction to distributed version control systems - IBM Developer Works article

- Git Interview Questions - Online Interview questions