Discworld (video game)

| Discworld | |

|---|---|

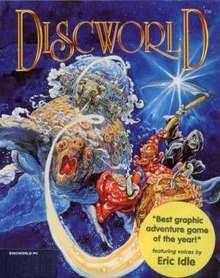

The cover features work by Discworld novel cover artist Josh Kirby. | |

| Developer(s) | |

| Publisher(s) | Psygnosis |

| Director(s) | Gregg Barnett |

| Producer(s) | Angela Sutherland |

| Designer(s) |

|

| Programmer(s) |

|

| Artist(s) |

|

| Writer(s) |

|

| Composer(s) |

|

| Platform(s) | MS-DOS, Mac OS, PlayStation, Sega Saturn |

| Release |

MS-DOSMac OS

|

| Genre(s) | Adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Discworld is a 1995 point-and-click adventure game developed by Teeny Weeny Games and Perfect 10 Productions for MS-DOS, Macintosh, and the Sony PlayStation. A Sega Saturn version was released the following year. The game stars Rincewind the Wizard (voiced by Eric Idle) and is set on Terry Pratchett's Discworld. The plot is based roughly around the events in the book Guards! Guards!, but also borrows elements from other Discworld novels. It involves Rincewind attempting to stop a dragon terrorising the inhabitants of Ankh-Morpork.

The game was developed because the designer Gregg Barnett wanted a large adventure for CD-based systems. A licence was difficult to obtain; Pratchett was reluctant to grant one as he wanted a Discworld game to be developed by a company with a reputation and who cared about the property. An original story was created due to Barnett having difficulty basing games on one book. Discworld was praised for its humour, voice-acting and graphics, though some criticised its gameplay and difficult puzzles. Discworld was followed by a sequel, Discworld II: Missing Presumed...!?, in 1996.

Gameplay

Discworld is a third-person point-and-click graphic adventure game.[1][2] An overhead map appears when leaving a location that allows the player to go straight to another.[2][3] Locations featured include the Unseen University, the Broken Drum (a pub), and the Shades (where the city's "exciting nightlife" reside).[3] Locations outside Ankh-Morpork include the Dark Wood (where Nanny Ogg resides), the Mines (where dwarves tune swords), and the Edge of the World (where "the world ends and space begins").[3] Items can be examined or used,[2] and can either be stored in Rincewind's pockets or in the Luggage.[1] To progress in the game, Rincewind must collect items, talk to people and solve puzzles.[4] Rincewind may also acquire special skills needed to perform certain tasks.[5] Characters featured include an Archchancellor, the Dibbler, the Librarian, and Death.[6] During a conversation, the player may choose to have Rincewind greet, joke with, vent anger towards, or pose a question to the character.[5]

The PlayStation version is compatible with the PlayStation Mouse, as well as the standard PlayStation controller.[7]

Plot

A secret brotherhood summons a dragon from its native dimension, so as to cause destruction and mayhem across the city of Ankh-Morpork.[8] Rumours of the dragon's rampage across the city reaches Unseen University. Since the Archchancellor wishes the involvement of at least one wizard in the matter, Rincewind is summoned to handle the problem. After acquiring a book to learn what is needed to track the dragon to its lair, Rincewind searches the city for the various components needed to assemble a dragon detector and brings them back to the Archchancellor. After the Archancellor lets slip that the dragon's lair is stocked with gold, Rincewind snatches the dragon detector from him, searches the city, finds the lair, and takes all the gold within it. Just before he leaves, the dragon stops him and requests his aid in removing the brotherhood's hold upon her, claiming they are using her for evil and are planning to make her go on a major rampage.[9]

To do this, Rincewind is told to discover who they are, and recover a golden item from each, since these items are what they use to control the dragon.[10] Learning that a book about summoning dragons had been stolen from the library at Unseen University the night before, Rincewind gains access to L-Space, allowing him to journey into the past, witness the theft, and follow the thief back to the brotherhood's hideout. After gaining entry in disguise, Rincewind learns that each member holds a role in the city — Chucky the Fool, the Thief, the Mason, the Chimney Sweep, the Fishmonger, and the Dunny King — and seeks to change the city so they can have a better future for themselves. Acquiring their golden items, Rincewind brings them to the dragon, only to learn it will not return to its dimension but seek revenge on the brotherhood before coming after him. Wishing to stop this, Rincewind decides to prevent the summoning book from being stolen, by switching it for one that makes love custard. In his efforts to be recognised for stopping the dragon, Rincewind gets into an argument with the Patrician over the existence of dragons, summoning the very same one back to Discworld. An annoyed Patrician tasks Rincewind to deal with it.[11]

Learning that a hero with a million-to-one chance can stop it, Rincewind searches for the right components to be that hero, journeying across the city, the Disc, and even over the edge, to find the necessary items, including a sword that goes "ting", a birthmark, and a magic spell. With the components acquired, he returns to the city's square, where Lady Ramkin, the owner of a local dragon sanctuary, is tied to a rock to be sacrificed to the dragon. Despite having what is needed to combat the dragon, Rincewind fails to stop it, and so seeks out an alternative method.[12] Taking a swamp dragon called Mambo the 16th, and feeding him hot coals and a lit firecracker, Rincewind tries again, but Mambo stops working when he becomes infatuated with the dragon. Rincewind then throws a love custard tart at the dragon. The dragon falls in love with Mambo, and the two fly off to perform mating dances. Rincewind heads to the pub for a pint to celebrate the end of his adventure.[13]

Development

Terry Pratchett was pleased with the 1986 interactive fiction game The Colour of Magic, but criticised its poor marketing.[14] He was reluctant to grant Discworld licences due to concern for the series, and wanted a reputable company who cared about the property.[15][14] Other video game companies had previously approached Pratchett seeking a licence.[15] One such company was AdventureSoft, and their failure to obtain a Discworld licence led to the creation of Simon the Sorcerer, which took inspiration from the Discworld series of books.[16][17]

When the creative director and designer Gregg Barnett sought out the Discworld licence, he intended to show Pratchett that he cared about Discworld, rather than seeking money. During negotiations, he offered to design the game before signing a deal. He did so, and Pratchett agreed. Gregg stated that the design showed respect for Discworld, and that was what persuaded Pratchett.[15] This took roughly six months, and Pratchett was impressed with a demonstration of Rincewind using a broom to get the Luggage off the top of a wardrobe.[14] Perfect 10 Productions developed an engine, which was developed in a separate location to "keep the code clean". The dialogue was refined by Pratchett. The character design was based on Barnett giving his interpretation of characters to a character designer who had worked for Disney. He stated that they "went a bit slapstick on it".[15] The backdrops were painted manually and digitised.[18]

Pratchett originally wanted the game to be based on The Colour of Magic and for the team to work in succession through the series, but Barnett believed that would be detrimental, and thought that it was difficult to make a game based on just one book. He explained that they wanted to licence all of Discworld. An original story was made, taking elements from various Discworld books, particularly The Colour of Magic and Guards! Guards!. Barnett stated that the team had "effectively written a complete film script for the game". The game introduced a new character: a practising psychiatrist (known as the psychatrickerist).[19] Pratchett initially objected to this, but later added his input, and the character became a retro-phrenologist. Barnett stated that he wanted to create Discworld as a flagship game for CD-based systems, and thought the Discworld licence was "100% suited".[14]

Barnett stated that he wanted to improve the British comedy by hiring voice actors with "British talent". John Cleese was his first choice for Rincewind, but he rejected the offer saying that he did not do games. Pratchett wanted Nicholas Lyndhurst for Rincewind because he was physically based on his Only Fools and Horses character. Eric Idle was cast as Rincewind, who was tweaked to make him more like Idle from Monty Python. Other voice actors include Tony Robinson, Kate Robbins (who voiced every female character), Rob Brydon, Nigel Planer, Robert Llewellyn, and Jon Pertwee. Barnett wanted Christopher Lee as Death, but was unable to afford him. Brydon had already been recorded when he offered to voice Death.[15] Barnett initially believed that Rowan Atkinson "would make a great Death".[14]

The game was originally due to be published by Sierra On-line. Their engine was obtained and worked on, but due to costs for another project, they cancelled all external development. An advert in Computer Trade Weekly attracted interest from companies such as Electronic Arts and Psygnosis. The latter approached Perfect 10 Productions and would not leave until a deal was signed. Psygnosis had offered Pratchett "a big cheque", which he refused.[15]

The game was officially announced by September 1993 and slated for a Christmas release the following year.[20] It was released in 1995 for the PC, PlayStation, and Macintosh.[6][21][22] The Saturn version was released in Europe on 15 August 1996,[23] and in Japan on 13 December 1996.[24]

The game was released on both floppy disk and CD-ROM, with the CD version featuring a fully voiced cast of characters.[25] For the Japanese PlayStation and Saturn releases, all voice acting was redone by a prominent Japanese comedian, a major selling point for the game in Japan.[26] A port had been under way for the Philips CD-i in 1996, and had entered its final stages of development,[27] but was never released.[28]

Reception

| Reception | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Discworld was a "massive hit" in Europe and the United Kingdom, according to director Gregg Barnett. However, the game was less successful in the United States.[38] It received generally positive reviews. The humour and graphics in particular were widely praised, but some thought that the difficulty was too harsh. It tied for third place in Computer Game Review's 1995 "Adventure Game of the Year" award category. The editors noted its "good voice work" and "very nice animation", and praised its humour.[39]

Entertainment Weekly praised the voice-acting of Eric Idle, but criticised the PlayStation version, saying that it was difficult to navigate without the PlayStation Mouse and that the text was too small.[7] In their review of the PlayStation version, Electronic Gaming Monthly similarly commented that the PlayStation mouse is required for full enjoyment, but highly praised the voice acting, humour, and graphics.[21] Scary Larry of GamePro, in contrast to EW and EGM, said the standard joypad "works just as well" as the PlayStation Mouse. He praised the humorous graphics, extensive voice acting, and script which "will leave your sides aching from laughter", but found the gameplay too simplistic and lacking in challenge. He recommended it for players who were open to less serious gaming.[40] IGN called Discworld challenging and long, but criticised the long loading times.[4] The reviewer of Joypad described the game as "very beautiful" and said that the PlayStation version has more colours than the PC version, but disliked the difficulty and the size of the save game files.[35]

Sega Saturn Magazine cited overlong dialogues, poor graphics, and "largely non-existent" animation, but complimented the variety of locations to visit and their mediaeval backdrops, and described the dialogue as "jokey" and "sarcastic".[32] The magazine's Japanese namesake agreed with this assessment of "British" humour by describing it as ironic and amusing.[24] Mean Machines Sega's reviewers believed the Saturn version had lost some authenticity, and thought that the gags were not funny, but complimented the storyline.[34]

Reviewing the PC version, Coming Soon Magazine's reviewer believed that the graphics are colourful and liked the humour, but criticised the way the dialogue was handled.[33] David Tanguay of Adventure Classic Gaming described Discworld as "one of the funniest adventure games ever made", but recommended that players use a walkthrough.[25] Computer Gaming World's Charles Ardai praised the humour and believed the writing was true to Pratchett.[30] PC Gamer's reviewer praised the speech, believing it greatly improved the humour, and also complimented the difficulty, saying the game cannot be completed within days. His criticisms included the overuse of dialogue in the first act, saying most of it is irrelevant to the story, and also thought the control system "falters in certain areas". He stated that Discworld is "a worthy contender" to Sam & Max and challenged the hold LucasArts had on the point-and-click genre.[31] The graphics and animation were criticised as "merely average" by Christopher Lindquist of PC Games, although he claimed that fans of Pratchett "won't mind" the game and described it as "A smart, funny--and long--gaming tribute" to the series.[36]F The Macintosh version was described by Génération 4 as "the gag of the year!"; the reviewer liked the humour and decoration, but criticised it for only being compatible with Motorola 6800-based systems.[22] Adventure Gamers praised the voice acting, graphics, humour and story, calling it "a wonderful game", but noted that "it stops short of being a classic simply due to its sheer difficulty and the unwieldy nature". Adventure Gamers also called the music "serviceable at best, and fairly forgettable".[2] In 2009 Eurogamer's Will Porter reviewed the game retrospectively, praising the game's cartoonish graphics and voice-acting, but criticising its puzzles and noting that "Discworld commits every point-and-click crime you'd care to mention" (such as "obtuse puzzles").[41] The game was reviewed in 1995 in Dragon by David "Zeb" Cook in the final "Eye of the Monitor" column. Cook praised the "exceptional" animation and art, as well as the "faithful" conversion of Pratchett's work to a video game, but criticised the testing and quality control as "crappy".[42] Next Generation recommended the game for fans of Douglas Adams or Monty Python.[37]

Entertainment Weekly's Darren Franich in 2010 called the game an "underrated point-and-click gem", saying that it was one of the games he wanted on the PlayStation Network.[43] In 2013, Retro Gamer cited Discworld as an example demonstrating that British developers produced a disproportionately large number of overly hard video games.[44]

References

- 1 2 David Tanguay (15 October 1997). "Discworld". Adventure Classic Gaming. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rob Michaud (1 July 2005). "REVIEW: Discworld". Adventure Gamers. Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Visitor's Guide to Ankh-Morpork" (Map). Discworld Official Strategy Guide. 1995.

- 1 2 3 IGN Staff (21 November 1996). "Discworld". IGN. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- 1 2 Discworld Instruction Manual (PlayStation PAL ed.). Psygnosis. 1995. p. 11.

- 1 2 "The Classic Game: Discworld". Retro Gamer. No. 94. Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing. pp. 72, 73. ISSN 1742-3155.

- 1 2 "Discworld". Entertainment Weekly. No. 310. 19 January 1996. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ↑ Perfect 10 Productions (1995). Discworld. Psygnosis. Scene: Introduction.

- ↑ "Act One: In Search of a Dragon". Official Strategy Guide. pp. 12–39.

- ↑ Official Strategy Guide. pp. 38, 39.

- ↑ "Act Two: All That Glitters". Official Strategy Guide. pp. 42–79.

- ↑ "Act Three: A Million to One Chance". Official Strategy Guide. pp. 82–129.

- ↑ "Act Four: The Final Showdown". Official Strategy Guide. pp. 132–135.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Whitta, Gary (December 1993). "Terry Pratchett: Going by the Book". PC Gamer. No. 1. Future Publishing. pp. 54–61. ISSN 1470-1693. Archived from the original on 18 April 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "The History Of Discworld". Retro Gamer. No. 164. Bath: Future plc. pp. 82–89. ISSN 1742-3155.

- ↑ "Behind The Scenes Simon The Sorcerer". GamesTM. No. 82. Imagine Publishing. pp. 138–143. ISSN 1478-5889.

- ↑ "Simon The Sorcerer". Blueprint. PC Zone. No. 5. London: Dennis Publishing. August 1993. pp. 74–77. ISSN 0967-8220.

- ↑ "Discworld". Blueprint. PC Zone. No. 20. London: Dennis Publishing. November 1994. pp. 50–51. ISSN 0967-8220.

- ↑ Andrew Blair (8 May 2015). "Looking back at the Discworld videogame". Den of Geek. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ "Welcome to Discworld!". The One. EMAP Images. September 1993. p. 14. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Discworld" (PDF). Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 76. Sendai Publishing. November 1995. p. 48. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 Ronan Fournier-Christol (September 1995). "Discworld". Génération 4 (in French). No. 80. p. 124,125. ISSN 1624-1088.

- ↑ "Checkpoint" (PDF). Computer and Video Games. No. 178. September 1996. p. 52. ISSN 0261-3697. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- 1 2 "ディスクワールド" [Discworld] (PDF). Sega Saturn Magazine (in Japanese). Tokyo: SoftBank Publishing. 13 December 1996. p. 270. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 David Tanguay (15 October 1997). "Discworld". Adventure Classic Gaming. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ↑ "New Games Frenzy!: PlayStation Expo". Maximum: The Video Game Magazine. No. 2. EMAP International. November 1995. pp. 122–3. ISSN 1360-3167. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

Meanwhile, the Japanese software house, Media Entertainment, drew some interest with a conversion of Discworld, not least because the voice-overs are by a prominent Japanese comedian.

- ↑ Ramshaw, Mark (June 1996). "Discworld". CDi Magazine. No. 18. Haymarket Publishing. pp. 20–24. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ↑ Bas (23 October 2006). "Discworld on CD-i: Lost forever?". Interactive Dreams. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ↑ "Discworld". GameRankings. Archived from the original on 9 August 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- 1 2 Charles Ardai (June 1995). "Dying Is Easy, Comedy Is Hard" (PDF). Computer Gaming World. No. 131. Ziff Davis. pp. 98–102. ISSN 0744-6667. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- 1 2 "Discworld". PC Gamer. Vol. 2 no. 4. Bath: Future plc. March 1995. pp. 36, 37. ISSN 1470-1693.

- 1 2 Bright, Rob (June 1996). "Discworld" (PDF). Sega Saturn Magazine. No. 8. Emap International Limited. pp. 70–71. ISSN 1360-9424. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- 1 2 "Discworld by Psygnosis". Coming Soon Magazine. 1995. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- 1 2 "Discworld". Mean Machines Sega. No. 45. Peterborough: Emap International Limited. July 1996. pp. 72, 73. ISSN 0967-9014. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- 1 2 "Discworld". Joypad (in French). No. 46. October 1995. p. 85. ISSN 1163-586X.

- 1 2 Christopher Lindquist (July 1995). "Discworld". PC Games. Archived from the original on 18 October 1996.

- 1 2 "Finals". Next Generation. No. 5. Imagine Media. May 1995. p. 93.

- ↑ Bronstring, Marek; Saveliev, Nick (20 April 1999). "Adventure Gamer - Interviews - Discworld Noir". Adventure Gamers. Archived from the original on 17 August 2000.

- ↑ Staff (April 1996). "CGR's Year in Review". Computer Game Review. Archived from the original on 18 October 1996.

- ↑ "Discworld". GamePro. No. 88. IDG. January 1996. p. 134. ISSN 1042-8658.

- ↑ Will Porter (26 June 2009). "Retrospective: Discworld". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on 9 October 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ↑ Cook, David "Zeb" (November 1995). "Discworld" (PDF). Dragon. No. 223. pp. 64–66. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ↑ Darren Franich (5 April 2010). "'Perfect Dark' hits Xbox Live Arcade: What other classic games deserve a resurrection?". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 10 April 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ↑ Locke, Phil (December 2013). "Creating Chaos". Retro Gamer. No. 122. Imagine Publishing. p. 71. ISSN 1742-3155.

Sources

- Glen Edridge (1995). Discworld The Official Strategy Guide. Prima Publishing. ISBN 978-0552-144-391.