Debasement

Debasement is the practice of lowering the value of currency. It is particularly used in connection with commodity money such as gold or silver coins. A coin is said to be debased if the quantity of gold, silver, copper or nickel is reduced.

Examples

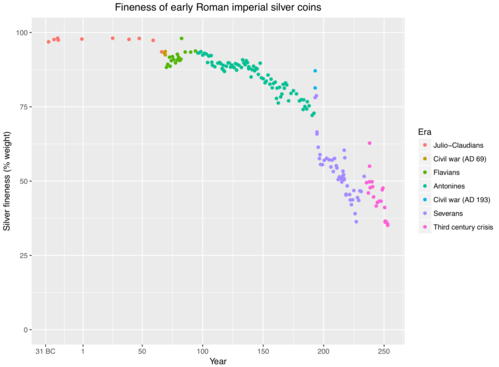

For example, the value of the denarius in Roman currency gradually decreased over time as the Roman government altered both the size and the silver content of the coin. Originally, the silver used was nearly pure, weighing about 4.5 grams. From time to time, this was reduced. During the Julio-Claudian dynasty, the Denarius contained approximately 4 grams of silver, and then was reduced to 3.8 grams under Nero. The Denarius continued to shrink in size and purity, until by the second half of the third century, it was only about 2% silver, and was replaced by the Argenteus.[1]

Because of huge wealth, the Vijayanagara Empire in modern-day South India issued large quantities of gold coins. Harihara I and Bukka Raya I, who founded the Vijayanagar Empire, minted gold coins using debased gold. Gold fanams (a type of coin) and its fractions were minted by them for medium-end transactions.[2]

Reasons for debasement

One reason a government will debase its currency is financial gain for the sovereign at the expense of citizens. By reducing the silver or gold content of a coin, a government can make more coins out of a given amount of specie. Inflation follows, allowing the sovereign to pay off or repudiate government bonds.[3] However, the purchasing power of the citizens’ currency has been reduced. Another reason is to end a deflationary spiral.

Debasement was also the result of the value of the precious metal content rising above the face value of coins. As the market price of precious metal rose, the intrinsic value of coins would eventually rise above the face value and so a profit could be made from using coins as bullion rather than monetary instrument. This gave an incentive to money changers and mint masters to practice illegal debasement via clipping and sweating. Coins would also be melted down and exported. To anticipate these illegal debasements and preserve the quality and quantity of coins, the king would either debase or cry up the coinage (i.e., raise the face value of coins). Thus, debasement had its legitimate purposes and was welcome by the population if done to preserve the stability of the coinage. [4]

Effects of debasement

Debasement lowers the intrinsic value of the coinage and so more coins can be made with the same quantity of precious metal. If done too frequently, debasement may lead to a new coin being adopted as a standard currency, as when the Ottoman Akçe was replaced by the kuruş (1 kuru = 120 akçe), with the para (1/40 kuruş) as a subunit. The kuruş in turn later became a subdivision of the lira.

Methods of debasement

- Methods of coin debasement

- The mint starts issuing coins of a certain face value, but with less metal content than previous issues. There will be an incentive to bring the old coins to the mint for re-minting – see Gresham's law. A revenue, called seigniorage, is made on this minting process.

Related uses

- "Debasement" is also sometimes used to refer to the tendency of silver or gold coins to be "shaved", that is, to have small amounts shaved off the edges of the coins by unscrupulous users, thereby reducing the actual precious metal content of the coin. In order to prevent this, silver and gold coins began to be produced with milled edges, as many coins still do by tradition, although they no longer contain valuable metals. For example, the U.S. quarter and dime have milled edges. Coins that have traditionally been made purely of base metals, such as the U.S. nickel or the penny, are more likely to have unmilled edges.

- By analogy, "debased currency" is sometimes used for anything whose value has been reduced, such as "Stardom is an utterly debased currency" [5]

See also

- Financial repression, similar process via different mechanism

- Money burning

References

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-11-28. Retrieved 2015-12-01.

- ↑ http://www.forumancientcoins.com/india/vijayngr/vij_coinage.html

- ↑ Milton Friedman (1990). Free to choose: a personal statement. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 269.

- ↑ Ralph George Hawtrey (1919). Currency and Credit. Longmans, Green and Co. pp. 280–281.

- ↑ https://www.telegraph.co.uk/sport/2425642/Star-no-longer-a-big-enough-word-for-peerless-Wilkinson.html