Cyanotype

| Alternative photography |

|---|

|

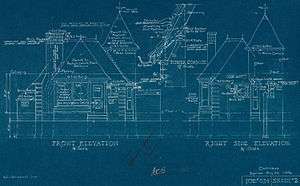

Cyanotype is a photographic printing process that produces a cyan-blue print. Engineers used the process well into the 20th century as a simple and low-cost process to produce copies of drawings, referred to as blueprints. The process uses two chemicals: ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide.

History

The English scientist and astronomer Sir John Herschel discovered the procedure in 1842.[1] Though the process was developed by Herschel, he considered it as mainly a means of reproducing notes and diagrams, as in blueprints.[2]

Anna Atkins created a series of cyanotype limited-edition books that documented ferns and other plant life from her extensive seaweed collection,[3] placing specimens directly onto coated paper and allowing the action of light to create a silhouette effect. By using this photogram process, Anna Atkins is sometimes considered the first female photographer.[4]

Numerous contemporary artists employ the cyanotype process in their art: Christian Marclay, Marco Breuer, Kate Cordsen, Hugh Scott-Douglas and WuChi-Tsung.

Process

In a typical procedure, equal volumes of an 8.1% (w/v) solution of potassium ferricyanide and a 20% solution of ferric ammonium citrate are mixed. The overall contrast of the sensitizer solution can be increased with the addition of approximately 6 drops of 1% (w/v) solution potassium dichromate for every 2 ml of sensitizer solution.

This mildly photosensitive solution is then applied to a receptive surface (such as paper or cloth) and allowed to dry in a dark place. Cyanotypes can be printed on any surface capable of soaking up the iron solution. Although watercolor paper is a preferred medium, cotton, wool and even gelatin sizing on nonporous surfaces have been used. Care should be taken to avoid alkaline-buffered papers, which degrade the image over time.

Prints can be made from large format negatives and lithography film, Digital negative (transparency) or everyday objects can be used to make photograms.

A positive image can be produced by exposing it to a source of ultraviolet light (such as sunlight) as a contact print through the negative(traditionally, semitransparent paper) or objects. The combination of UV light and the citrate reduces the iron(III) to iron(II). This is followed by a complex reaction of the iron(II) complex with ferricyanide. The result is an insoluble, blue dye (ferric ferrocyanide) known as Prussian blue.[5] The extent of color change depends on the amount of UV light, but acceptable results are usually obtained after 10–20 minute exposures on a dark, gloomy day.

After exposure, developing of the picture involves the yellow unreacted iron solution being rinsed off with running water. Although the blue color darkens upon drying, the effect can be accelerated by soaking the print in a 6% (v/v) solution of 3% (household) hydrogen peroxide. The water-soluble iron(III) salts are washed away, while the non-water-soluble Prussian blue remains in the paper. This is what gives the picture its typical blue color.[5] The highlight values should appear overexposed, as the water wash reduces the final print values.

Toning

In a cyanotype, a blue is usually the desired color; however, there are a variety of effects that can be achieved. These fall into three categories: reducing, intensifying, and toning.[6]

- Reducing is the process of reducing or decreasing the intensity of the blue. Sodium carbonate, ammonia, Clorox, TSP, borax, Dektol and other chemicals can be used to do this. A good easily obtained reducer is bleach. Bleaching takes some patience. How much and how long to bleach depends on the image content, emulsion thickness and what kind of toning is being used.[7] When using a reducer it is important to pull the cyanotype out of the weak solution and put the cyanotype into a water bath to arrest the bleaching process.[7]

- Intensifying is the strengthening of the blue effect. These chemicals can also be used to expedite the oxidation process the cyanotype undergoes. These chemicals are hydrogen peroxide, citric acid, lemon juice, and vinegar.[6]

- Toning is the process used to change the color of the iron in the print cyanotype.[6] The color change varies with the reagent used. There are a variety of elements that can be used, including tannic acid, oolong tea, wine, cat urine, and pyrogallic acid.[6]

Long-term preservation

In contrast to most historical and present-day processes, cyanotype prints do not react well to basic environments.[8] As a result, it is not advised to store or present the print in chemically buffered museum board, as this makes the image fade. Another unusual characteristic of the cyanotype is its regenerative behavior: prints that have faded due to prolonged exposure to light can often be significantly restored to their original tone by simply temporarily storing them in a dark environment.

Cyanotypes on cloth are permanent but must be washed by hand with non-phosphate soap[9] so as to not turn the cyan to yellow.

Largest cyanotype

The world's current largest cyanotype was created on 18 September 2017 in Thessaloniki, Greece at the seaside [10]. It was 276.64 square metres (2,977.7 sq ft) (98.80 metres (324.1 ft) by 2.80 metres (9.2 ft)). Team Stef Tsakiris, who made the attempt, wanted to promote artistic expression and collaboration on a local level in the city of Thessaloniki. The artwork was created with the aim of teaching people about cyanotype photography technique, and to increase environmental awareness.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to cyanotypes. |

- Sepia

- Monochrome

- Film tinting

- Spirit duplicator

- Mimeograph

- Cyanography

- Duotone

References

- Notes

- ↑ "Exploring Photography – Photographic Processes – Cyanotype". V&A. 2012-11-13. Retrieved 2012-12-22.

- ↑ "The Cyanotype". Vernacular Photography. 2012-12-12. Retrieved 2012-12-22.

- ↑ "Anna Atkins, British, 1799–1871". Leegallery.com. Archived from the original on 2010-08-29. Retrieved 2012-12-22.

- ↑ "Exploring Photography – Photographers – Anna Atkins". V&A. 2012-11-13. Archived from the original on December 11, 2003. Retrieved 2012-12-22.

- 1 2 "General View of Niagara Falls from Bridge". World Digital Library. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Berkowitz, Steven. "Hybrid Photography - Cyanotype Toners" (PDF).

- 1 2 "Cyanotype toning: the basics". mpaulphotography. 2011-04-01. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Hannavy, John (2013-12-16). Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. Routledge. ISBN 9781135873271.

- ↑ "Washing instructions for cloth". blueprintsonfabric.com.

- ↑ "Largest cyanotype photograph". www.guinnessworldrecords.com.

- Further reading

- Atkins, Anna (1985). Sun Gardens: Victorian Photograms. With text by Larry J. Schaaf. New York: Aperture. ISBN 0-89381-203-X.

- Blacklow, Laura (2000). New Dimensions in Photo Processes: a step by step manual (3rd ed.). Boston: Focal Press. ISBN 0-240-80431-7.

- Ware, M. (1999). Cyanotype: the history, science and art of photographic printing in Prussian blue. Science Museum, UK. ISBN 1-900747-07-3.

- Crawford, William (1979). The Keepers of Light. New York: Morgan and Morgan. ISBN 0-87100-158-6.

- Loos, Ted (February 5, 2016). "Cyanotype: Photography's Blue Period is Making a Comeback". New York Times. Worcester, MA.

External links

- Mike Ware's New Cyanotype – A new version of the cyanotype that address some of the classical cyanotype's shortcomings as a photographic process.

- The largest cyanotype photograph

- Gallery of over 100 artists working in cyanotypes on AlternativePhotography.com

- Brown, G.E. (1900). "Ferric and heliographic processes". London.

- "Photographic reproduction processes. A practical treatise of the photo-impressions without silver salts ..." 1891.