Cubist sculpture

Cubist sculpture developed in parallel with Cubist painting, beginning in Paris around 1909 with its proto-Cubist phase, and evolving through the early 1920s. Just as Cubist painting, Cubist sculpture is rooted in Paul Cézanne's reduction of painted objects into component planes and geometric solids; cubes, spheres, cylinders, and cones. Presenting fragments and facets of objects that could be visually interpreted in different ways had the effect of 'revealing the structure' of the object. Cubist sculpture essentially is the dynamic rendering of three-dimensional objects in the language of non-Euclidean geometry by shifting viewpoints of volume or mass in terms of spherical, flat and hyperbolic surfaces.

History

%2C_plaster_lost%2C_photo_Galerie_Ren%C3%A9_Reichard%2C_Frankfurt%2C_72dpi.jpg)

In the historical analysis of most modern movements such as Cubism there has been a tendency to suggest that sculpture trailed behind painting. Writings about individual sculptors within the Cubist movement are commonly found, while writings about Cubist sculpture are premised on painting, offering sculpture nothing more than a supporting role.[1]

We are better advised, writes Penelope Curtis, "to look at what is sculptural within Cubism. Cubist painting is an almost sculptural translation of the external world; its associated sculpture translates Cubist painting back into a semi-reality".[1] Attempts to separate painting and sculpture, even by 1910, are very difficult. "If painters used sculpture for their own ends, so sculptors exploited the new freedom too", writes Curtis, "and we should look at what sculptors took from the discourse of painting and why. In the longer term we could read such developments as the beginning of a process in which sculpture expands, poaching painting's territory and then others, to become steadily more prominent in this century".[1]

Increasingly, painters claim sculptural means of problem solving for their paintings. Braque's paper sculptures of 1911, for example, were intended to clarify and enrich his pictorial idiom. "This has meant" according to Curtis, "that we have tended to see sculpture through painting, and even to see painters as poaching sculpture. This is largely because we read Gauguin, Degas, Matisse, and Picasso as painters even when looking at their sculpture, but also because their sculptures often deserve to be spoken of as much as paintings as sculptures".[1]

%2C_modeled_on_Fernande_Olivier.jpg)

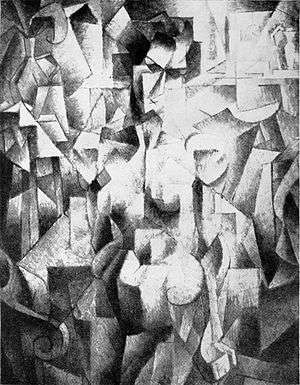

A painting is meant both to capture the palpable three-dimensionality of the world revealed to the retina, and to draw attention to itself as a two-dimensional object, so that it is both a depiction and an object in itself.[2] Such is the case for Picasso's 1909-10 Head of a Woman (Head of Fernande), often considered the first Cubist sculpture.[3][4] Yet Head of a Woman, writes Curtis, "had mainly revealed how Cubism was more interesting in Painting—where it showed in two dimensions how to represent three dimensions—than in sculpture".[1] Picasso's Head of a Woman was less adventurous than his painting of 1909 and subsequent years.[5]

Though it is difficult to define what can properly be called a 'Cubist sculpture', Picasso's 1909-10 Head bares the hallmarks of early Cubism in that the various surfaces constituting the face and hair are broken down into irregular fragments that meet at sharp angles, rendering practically unreadable the basic volume of the head beneath. These facets are obviously a translation from two to three dimensions of the broken planes of Picasso's 1909-10 paintings.[6]

According to the art historian Douglas Cooper, "The first true Cubist sculpture was Picasso's impressive Woman's Head, modeled in 1909-10, a counterpart in three dimensions to many similar analytical and faceted heads in his paintings at the time."[7]

.jpg)

It has been suggested that in contrast to Cubist painters, Cubist sculptors did not create a new art of 'space-time'. Unlike a flat painting, high-relief sculpture from its volumetric nature could never be limited to a single view-point. Hence, as Peter Collins highlights, it is absurd to state that Cubist sculpture, like painting, was not limited to a single point of view.[11]

The concept of Cubist sculpture may seem "paradoxical", writes George Heard Hamilton, "because the fundamental Cubist situation was the representation on a two-dimensional surface of a multi-dimensional space at least theoretically impossible to see or to represent in the three dimensions of actual space, the temptation to move from a pictorial diagram to its spatial realization proved irresistible".[5]

Now liberated from the one-to-one relationship between a fixed coordinate in space captured at a single moment in time assumed by classical vanishing-point perspective, the Cubist sculptor, just as the painter, became free to explore notions of simultaneity, whereby several positions in space captured at successive time intervals could be depicted within the bounds of a single three-dimensional work of art.[12]

Of course, 'simultaneity' and 'multiple perspective' were not the only characteristics of Cubism. In Du "Cubisme" the painters Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger write:

- "Some, and they are not the least intelligent, see the aim of our technique in the exclusive study of volumes. If they were to add that it suffices, surfaces being the limits of volumes and lines those of surfaces, to imitate a contour in order to represent a volume, we might agree with them; but they are thinking only of the sensation of relief, which we hold to be insufficient. We are neither geometers nor sculptors: for us lines, surfaces, and volumes are only modifications of the notion of fullness. To imitate volumes only would be to deny these modifications for the benefit of a monotonous intensity. As well renounce at once our desire for variety. Between reliefs indicated sculpturally we must contrive to hint at those lesser features which are suggested but not defined."[13]

%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_51.4_x_68.6_cm%2C_Fogg_Art_Museum%2C_Harvard_University.jpg)

More astonishing still, writes John Adkins Richardson, "is the fact that the artists participating in the [Cubist] movement not only created a revolution, they surpassed it, going on to create other styles of an incredible range and dissimilarity, and even devised new forms and techniques in sculpture and ceramic arts".[14]

"Cubists sculpture", writes Douglas Cooper, "must be discussed apart from the painting because it followed other paths, which were sometimes similar but never parallel".[7]

"But not infrequently the sculptor and the painter upset the equilibrium of the work of others by doing things which are out of key or out of proportion." (Arthur Jerome Eddy)[15]

The use of diverging vantage-points for representing the features of objects or subject matter became a central factor in the practice of all Cubists, leading to the assertion, as noted by the art historian Christopher Green, "that Cubist art was essentially conceptual rather than perceptual". Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes in their 1912 writing, along with the writings by the critic Maurice Raynal, were most responsible for the emphasis given to this claim. Raynal argued, echoing Metzinger and Gleizes, that the rejection of classical perspective in favor of multiplicity represented a break with the 'instantaneity' that characterized Impressionism. The mind now directed the optical exploration of the world. Painting and sculpture no longer merely recorded sensations generated through the eye; but resulted from the intelligence of both artist and observer. This was a mobile and dynamic investigation that explored multiple facets of the world.[2][16]

Proto-Cubist sculpture

%2C_for_the_top_of_The_Gates_of_Hell%2C_before_1886%2C_plaster.jpg)

The origins of Cubist sculpture are as diverse as the origins of Cubist painting, resulting from a wide range of influences, experiments and circumstances, rather than from one source. With its roots stemming as far back as ancient Egypt, Greece and Africa, the proto-Cubist period (englobing both painting and sculpture) is characterized by the geometrization of form. It is essentially the first experimental and exploratory phase, in three-dimensional form, of an art movement known from the spring of 1911 as Cubism.

The influences that characterize the transition from classical to modern sculpture range from diverse artistic movements (Post-Impressionism, Symbolism, Les Nabis and Neo-Impressionism), to the works of individual artists such as Auguste Rodin, Aristide Maillol, Antoine Bourdelle, Charles Despiau, Constantin Meunier, Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, Georges Seurat and Paul Gauguin (among others), to African art, Egyptian art, Ancient Greek art, Oceanic art, Native American art, and Iberian schematic art.

Before the advent of Cubism artists had questioned the treatment of form inherent in art since the Renaissance. Eugène Delacroix the romanticist, Gustave Courbet the realist, and virtually all the Impressionists had jettisoned Classicism in favor of immediate sensation. The dynamic expression favored by these artists presented a challenge to the static traditional means of expression.[18]

In his 1914 Cubists and Post-Impressionism Arthur Jerome Eddy makes reference to Auguste Rodin and his relation to both Post-Impressionism and Cubism:

The truth is there is more of Cubism in great painting than we dream, and the extravagances of the Cubists may serve to open our eyes to beauties we have always felt without quite understanding.

Take, for instance, the strongest things by Winslow Homer; the strength lies in the big, elemental manner in which the artist rendered his impressions in lines and masses which departed widely from photographic reproductions of scenes and people.

Rodin's bronzes exhibit these same elemental qualities, qualities which are pushed to violent extremes in Cubist sculpture. But may it not be profoundly true that these very extremes, these very extravagances, by causing us to blink and rub our eyes, end in a finer understanding and appreciation of such work as Rodin's?

His Balzac is, in a profound sense, his most colossal work, and at the same time his most elemental. In its simplicity, in its use of planes and masses, it is—one might say, solely for purposes of illustration—Cubist, with none of the extravagances of Cubism. It is purely Post-Impressionistic.[15]

%2C_partially_glazed_stoneware%2C_75_x_19_x_27_cm%2C_Mus%C3%A9e_d'Orsay%2C_Paris.jpg)

Several factors mobilized the shift from a representational art form to one increasingly abstract; a most important factor would be found in the works of Paul Cézanne, and his interpretation of nature in terms of the cylinder, the sphere, and the cone.[20] In addition to his tendency to simplify geometric structure, Cézanne was concerned with rendering the effect of volume and space. Cézanne's departure from classicism, however, would be best summarized in the complex treatment of surface variations (or modulations) with overlapped shifting planes, seemingly arbitrary contours, contrasts and values combined to produce a planar faceting effect. In his later works, Cézanne achieves a greater freedom, with larger, bolder, more arbitrary faceting, with dynamic and increasingly abstract results. As the colors planes acquire greater formal independence, defined objects and structures begin to lose their identity.[20]

Avant-garde artists working in Paris had begun reevaluating their own work in relation to that of Cézanne following a retrospective of his paintings at the Salon d'Automne of 1904, and exhibitions of his work at the Salon d'Automne of 1905 and 1906, followed by two commemorative retrospectives after his death in 1907. The influence generated by the work of Cézanne, in combination with the impact of diverse cultures, suggests a means by which artists (including Alexander Archipenko, Constantin Brâncuși, Georges Braque, Joseph Csaky, Robert Delaunay, Henri le Fauconnier, Albert Gleizes, Fernand Léger, Jean Metzinger, Amedeo Modigliani and Pablo Picasso) made the transition to diverse forms of Cubism.[21]

Yet the extreme to which the Cubist painters and sculptors exaggerated the distortions created by the use of multiple perspective and the depiction of forms in terms of planes is the late work of Paul Cézanne, led to a fundamental change in the formal strategy and relationship between artist and subject not anticipated by Cézanne.[2]

Africa, Egyptian, Greek and Iberian art

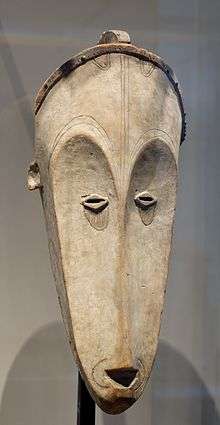

Another factor in the shift towards abstraction was the increasing exposure to Prehistoric art, and art produced by various cultures: African art, Cycladic art, Oceanic art, Art of the Americas, the Art of ancient Egypt, Iberian sculpture, and Iberian schematic art. Artists such as Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, André Derain, Henri Rousseau and Pablo Picasso were inspired by the stark power and stylistic simplicity of artworks produced by these cultures.[7]

Around 1906, Picasso met Matisse through Gertrude Stein, at a time when both artists had recently acquired an interest in Tribal art, Iberian sculpture and African tribal masks. They became friendly rivals and competed with each other throughout their careers, perhaps leading to Picasso entering a new period in his work by 1907, marked by the influence of ethnographic art. Picasso's paintings of 1907 have been characterized as proto-Cubism, as Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, the antecedent of Cubism.[7]

The African influence, which introduced anatomical simplifications, along with expressive features reminiscent of El Greco, are the generally assumed starting point for the Proto-Cubism of Picasso. He began working on studies for Les Demoiselles d'Avignon after a visit to the ethnographic museum at Palais du Trocadero. But that wasn't all. Aside from further influences of the Symbolists, Pierre Daix explored Picasso’s Cubism from a formal position in relation to the ideas and works of Claude Lévi-Strauss on the subject of myth. And too, without doubt, writes Podoksik, Picasso’s proto-Cubism came not from the external appearance of events and things, but from great emotional and instinctive feelings, from the most profound layers of the psyche.[22][23]

European artists (and art collectors) prized objects from different cultures for their stylistic traits defined as attributes of primitive expression: absence of classical perspective, simple outlines and shapes, presence of symbolic signs including the hieroglyph, emotive figural distortions, and the dynamic rhythms generated by repetitive ornamental patterns.[24]

These were the profound energizing stylistic attributes, present in the visual arts of Africa, Oceana, the Americas, that attracted not just Picasso, but many of the Parisian avant-garde that transited through a proto-Cubist phase. While some delved deeper into the problems of geometric abstraction, becoming known as Cubists, others such as Derain and Matisse chose different paths. And others still such as Brâncuși and Modigliani exhibited with the Cubists yet defied classification as Cubists.

In The Rise if Cubism Daniel Henry Kahnweiler writes of the similarities between African art with Cubist painting and sculpture:

In the years 1913 and 1914 Braque and Picasso attempted to eliminate the use of color as chiaroscuro, which had still persisted to some extent in their painting, by amalgamating painting and sculpture. Instead of having to demonstrate through shadows how one plane stands above, or in front of a second plane, they could now superimpose the planes one on the other and illustrate the relationship directly. The first attempts to do this go far back. Picasso had already begun such an enterprise in 1909, but since he did it within the limits of closed form, it was destined to fail. It resulted in a kind of colored bas-relief. Only in open planal form could this union of painting and sculpture be realized. Despite current prejudice, this endeavor to increase plastic expression through the collaboration of the two arts must be warmly approved; an enrichment of the plastic arts is certain to result from it. A number of sculptors like Lipchitz, Laurens and Archipenko have since taken up and developed this sculpto-painting.

Nor is this form entirely new in the history of the plastic arts. The negroes of the Ivory Coast have made use of a very similar method of expression in their dance masks. These are constructed as follows: a completely flat plane forms the lower part of the face; to this is joined the high forehead, which is sometimes equally flat, sometimes bent slightly backward. While the nose is added as a simple strip of wood, two cylinders protrude about eight centimeters to form the eyes, and one slightly shorter hexahedron forms the mouth. The frontal surfaces of the cylinder and hexahedron are painted, and the hair is represented by raffia. It is true that the form is still closed here; however, it is not the "real" form, but rather a tight formal scheme of plastic primeval force. Here, too, we find a scheme of forms and "real details" (the painted eyes, mouth and hair) as stimuli. The result in the mind of the spectator, the desired effect, is a human face."[25]

Just as in painting, Cubist sculpture is rooted in Paul Cézanne's reduction of painted objects into component planes and geometric solids (cubes, spheres, cylinders, and cones) along with the arts of diverse cultures. In the spring of 1908 Picasso worked on the representation of three-dimensional form and its position in space on a two-dimensional surface. "Picasso painted figures resembling Congo sculptures", wrote Kanhweiler, "and still lifes of the simplest form. His perspective in these works is similar to that of Cézanne".[25]

Cubist styles

._Reproduced_in_Archipenko-Album%2C_1921.jpg)

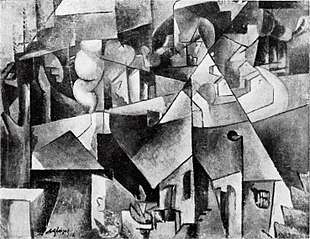

The diverse styles of Cubism have been associated with the formal experiments of Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso exhibited exclusively at the Kahnweiler gallery. However, alternative contemporary views on Cubism have formed to some degree in response to the more publicized Salon Cubists (Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Robert Delaunay, Henri Le Fauconnier, Fernand Léger, Alexander Archipenko and Joseph Csaky), whose methods and ideas were too distinct from those of Braque and Picasso to be considered merely secondary to them.[2] Cubist sculpture, just as Cubist painting, is difficult to define. Cubism in general cannot definitively be called either a style, the art of a specific group or even a specific movement. "It embraces widely disparate work, applying to artists in different milieux". (Christopher Green)[2]

Artist sculptors working in Montparnasse were quick to adopt the language of non-Euclidean geometry, rendering three-dimensional objects by shifting viewpoints and of volume or mass in terms of successive curved or flat planes and surfaces. Alexander Archipenko's 1912 Walking Woman is cited as the first modern sculpture with an abstracted void, i.e., a hole in the middle. Joseph Csaky, following Archipenko, was the first sculptor to join the Cubists, with whom he exhibited from 1911 onward. They were joined by Raymond Duchamp-Villon (1876-1918), whose career was cut short by his death in military service, and then in 1914 by Jacques Lipchitz, Henri Laurens and later Ossip Zadkine.[26][27]

According to Herbert Read, this has the effect of "revealing the structure" of the object, or of presenting fragments and facets of the object to be visually interpreted in different ways. Both of these effects transfer to sculpture. Although the artists themselves did not use these terms,[2] the distinction between "analytic cubism" and "synthetic cubism" could also be seen in sculpture, writes Read (1964): "In the analytical Cubism of Picasso and Braque, the definite purpose of the geometricization of the planes is to emphasize the formal structure of the motif represented. In the synthetic Cubism of Juan Gris the definite purpose is to create an effective formal pattern, geometricization being a means to this end."[28]

Alexander Archipenko

%2C_108_x_61.5_x_13.5_cm%2C_Tel_Aviv_Museum_of_Art._Reproduced_in_Archipenko-Album%2C_1921.jpg)

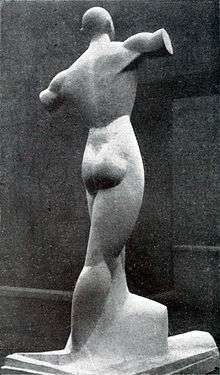

Alexander Archipenko studied Egyptian and archaic Greek figures in the Louvre in 1908 when he arrived in Paris. He was "the first", according to Barr, "to work seriously and consistently at the problem of Cubist sculpture". His torso entitled "Hero" (1910) appears related stylistically to Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, "but in its energetic three-dimensional torsion it is entirely independent of Cubist painting." (Barr)[29]

Archipenko evolved in close contact with the Salon Cubists (Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Henri Le Fauconnier, Robert Delaunay, Joseph Csaky and others). At the same time, his affinities with Futurism were documented by the British magazine The Sketch in October 1913, where Archipenko's Dancers (Dance), reproduced on its front cover, was described as a 'Futurist sculpture'.[30] "In this work", writes Alexandra Keiser, "two abstracted figures are engaged in a dynamic dance movement." Moreover, the chiaroscuro observed in the photographic reproduction "accentuated the artist's multi-faceted use of positive and negative space as a compositional element to create dynamic movement, in both the fragmentation of the dancers' bodies as well as in the void created between their bodies". In the photographic reproduction of Dancers, writes Keiser, "the sculpture is set off at an angle reinforcing the idea of dynamism and creating the illusion that the sculpture is propelled through space. The sculpture Dance itself as well as the style of its reproduction played strongly to the generalized notions of Futurism and to the idea that sculpture could be conceived as a specifically modern medium".[30]

Herwarth Walden of Der Sturm in Berlin described Archipenko as 'the most important sculptor of our time'.[31] Walden also promoted Archipenko as the foremost Expressionist sculptor. (Before World War I Expressionism encompassed several definitions and artistic concepts. Walden used the term to describe modern art movements including Futurism and Cubism).[30]

Archipenko's Woman with a Fan (1914) combines high-relief sculpture with painted colors (polychrome) to create striking illusions of volumetric space. Experimenting with the dynamic interplay of convex and concave surfaces, Archipenko created works such as Woman Combing her Hair (1915). Depending on the movement around the sculpture and effects of lighting, concave and convex surfaces appear alternately to protrude or recede. His use of sculptural voids was inspired by the philosopher Henri Bergson's Creative Evolution (1907) on the distortions of our understanding of reality, and how our intellect tends to define unanticipated circumstances positively or negatively. 'If the present reality is not one we are seeking, we speak of an absence of this sought reality wherever we find the presence of another'. "Archipenko's sculptural voids", write Antliff and Leighten, "allows us to fill this illusory gap with our own durational consciousness".[12]

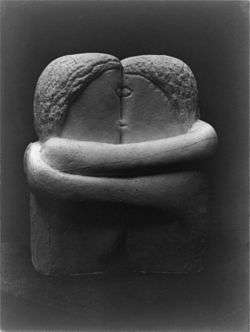

In 1914, Arthur Jerome Eddy examined what made Archipenko's sculpture, Family Life, exhibited at the Armory Show unique, powerful, modern and Cubist:

In his "Family Life," the group of man, woman, child, Archipenko deliberately subordinated all thought of beauty of form to an attempt to realize in stone the relation in life that is at the very basis of human and social existence.

Spiritual, emotional, and mathematical intellectuality, too, is behind the family group of Archipenko. This group, in plaster, might have been made of dough. It represents a featureless, large, strong male—one gets the impression of strength from humps and lumps—an impression of a female, less vivid, and the vague knowledge that a child is mixed up in the general embrace. The faces are rather blocky, the whole group with arms intertwined—arms that end suddenly, no hands, might be the sketch of a sculpture to be. But when one gets an insight it is intensely more interesting. It is, eventually, clear that in portraying his idea of family love the sculptor has built his figures with pyramidal strength; they are grafted together with love and geometric design, their limbs are bracings, ties of strength, they represent, not individuals, but the structure itself of family life. Not family life as one sees it, but the unseen, the deep emotional unseen, and in making his group when the sculptor found himself verging upon the seen—that is, when he no longer felt the unseen—he stopped. Therefore the hands were not essential. And this expression is made in the simplest way. Some will hoot at it, but others will feel the respect that is due one who simplifies and expresses the deep things of life. You may say that such is literature in marble—well, it is the most modern sculpture.

The group is so angular, so Cubist, so ugly according to accepted notions, that few look long enough to see what the sculptor means; yet strange as the group was it undeniably gave a powerful impression of the binding, the blending character of the family tie, a much more powerful impression than groups in conventional academic pose could give.[15]

Joseph Csaky

%2C_1913%2C_Plaster_lost_or_destroyed%2C_Published_in_Montjolie%2C_March_1914.jpg)

Joseph Csaky arrived in Paris from his native Hungary during the summer of 1908. By autumn of 1908 Csaky shared a studio space at Cité Falguière with Joseph Brummer, a Hungarian friend who had opened the Brummer Gallery with his brothers. Within three weeks, Brummer showed Csaky a sculpture he was working on: an exact copy of an African sculpture from the Congo. Brummer told Csaky that another artist in Paris, a Spaniard by the name of Pablo Picasso, was painting in the spirit of 'Negro' sculptures.[27]

Living and working at La Ruche in Montparnasse, Csaky exhibited his highly stylized 1909 sculpture Tête de femme (Portrait de Jeanne) at the 1910 Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, now significantly beyond the influence of Auguste Rodin. The following year he exhibited a proto-Cubist work entitled Mademoiselle Douell (1910).[32]

Csaky's proto-Cubist works include Femme et enfant (1909), collection Zborovsky, Tête de femme de profil (1909), exhibited Société National des Beaux-Arts, 1910, Tête de femme de face (1909). By 1910-11 Csaky's Cubist works included Tête d'homme, Autoportrait, Tête Cubiste (1911), exhibited at the Salon d'Automne of 1911.[33]

In 1911, Csaky exhibited his Cubist sculptures, including Mademoiselle Douell (no. 1831) at the Salon des Indépendants (21 April - 13 June) with Archipenko, Duchamp, Gleizes, Laurencin, La Fresnaye, Léger, Picabia and Metzinger. This exhibition provoked a scandal out of which Cubism was revealed to the general public for the first time. From that exhibition it emerged and spread throughout Paris and beyond.

Four months later Csaky exhibited at the Salon d'Automne (1 October - 8 November) in room XI together with the same artists, in addition to Modigliani and František Kupka, his Groupe de femmes (1911–1912), a massive, highly stylized block-like sculpture representing three women. At the same Salon Csaky exhibited Portrait de M.S.H., no. 91, his deeply faceted Danseuse (Femme à l'éventail, Femme à la cruche), no. 405, and Tête d'homme (Tête d'adolescent) no. 328, the first in a series of self-portraits that would become increasingly abstract in accord with his Cubist sensibility.[33]

The following spring, Csaky showed at the Salon des Indépendants (1913) with the same group, including Lhote, Duchamp-Villon and Villon.

Csaky exhibited as a member of Section d'Or at the Galerie La Boétie (10–30 October 1912), with Archipenko, Duchamp-Villon, La Fresnaye, Gleizes, Gris, Laurencin, Léger, Lhote, Marcoussis, Metzinger, Picabia, Kupka, Villon and Duchamp.

At the 1913 Salon des Indépendants, held March 9 through 18 May, Csaky exhibited his 1912 Tête de Femme (Buste de femme), an exceedingly faceted sculpture later purchased by Léonce Rosenberg.[33] The Cubist works were shown in room 46. Metzinger exhibited his large L'Oiseau bleu — Albert Gleizes, Albert Gleizes. Les Joueurs de football (Football Players) 1912-13, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C — Robert Delaunay The Cardiff Team (L'équipe de Cardiff ) 1913, Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven — Fernand Léger, Le modèle nu dans l'atelier (Nude Model In The Studio) 1912-13, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York — Juan Gris, L'Homme dans le Café (Man in Café) 1912, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The inspirations that led Csaky to Cubism were diverse, as they were for artists of Le Bateau-Lavoir, and other still of the Section d'Or. Certainly Cézanne's geometric syntax was a significant influence, as well as Seurat's scientific approach to painting. Given a growing dissatisfaction with the classical methods of representation, and the contemporary changes—the industrial revolution, exposure to art from across the world—artists began to transform their expression. Now at 9 rue Blainville in the fifth arrondissement in Paris Csaky—along with the Cubist sculptors who would follow—stimulated by the profound cultural changes and his own experiences, contributed his own personal artistic language to the movement.[27]

Csaky wrote of the direction his art had taken during the crucial years:

"There was no question which was my way. True, I was not alone, but in the company of several artists who came from Eastern Europe. I joined the cubists in the Académie La Palette, which became the sanctuary of the new direction in art. On my part I did not want to imitate anyone or anything. This is why I joined the cubists movement." (Joseph Csaky[27])

Joseph Csaky contributed substantially to the development of modern sculpture, both as an early pioneer in applying Cubist principles to sculpture, and as a leading figure in nonrepresentational art of the 1920s.[27]

Raymond Duchamp-Villon

Although some comparison can be drawn between the mask-like totemic characteristics of various Gabon sculptures, primitive art was well beyond the conservative French sensibilities visible in the work of Raymond Duchamp-Villon. Gothic sculpture, on the other hand, seems to have provided Duchamp-Villon the impetus for expressing novel possibilities of human representation, in a manner parallel to that provided by African art for Derain, Picasso, Braque and others.[6]

To his credit, Duchamp-Villon exhibited early on with the Cubists (Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Fernand Léger, Henri le Fauconnier, Roger de La Fresnaye, Francis Picabia, Joseph Csaky) at the 1912 Salon d'Automne; a massive public Cubist manifestation that caused yet another scandal, following from the Salon des Indépendants and Salon d'Automne of 1911. His role as architect of la Maison Cubiste (Cubist house) propelled him into the center of a politico-social scandal that accused the Cubists of foreign aesthetic inspiration.[34]

With the same group, including his brothers Jacques Villon and Marcel Duchamp, he exhibited at the Salon de la Section d'Or in the fall of 1912.

In Les Peintres Cubistes (1913) Guillaume Apollinaire writes of Duchamp-Villon:

- "The utilitarian end aimed at by most of the contemporary architects in the cause which keeps architecture considerably behind the other arts. The architect, the engineer should build with sublime intentions: to erect the highest tower, to prepare for time and the ivy, a ruin more beautiful than any other, to throw over a harbour or a river an arch more audacious than the rainbow, to compose above all a persistent harmony the most audacious that man has ever know.

- Duchamp-Villon has this titanic conception of architecture. A sculptor and architect, light in the only thing that counts for him, and for all the other arts also, it is only light which counts, the incorruptible light." (Apollinaire, 1913)[35]

Jacques Lipchitz

The early sculptures of Jacques Lipchitz, 1911-1912, were conventional portraits and figure studies executed in the tradition of Aristide Maillol and Charles Despiau.[36] He progressively turned toward Cubism in 1914 with periodic reference to Negro sculpture. His 1915 Baigneuse is comparable to figures from Gabun. In 1916 his figures became more abstract, though less so than those of Brâncuși's sculptures of 1912-1915.[29] Lipchitz' Baigneuse Assise (70.5 cm) of 1916 is clearly reminiscent of Csaky's 1913 Figure de Femme Debout, 1913 (Figure Habillée) (80 cm), exhibited in Paris at the Salon des Indépendants in the spring of 1913, with the same architectonic rendering of the shoulders, head, torso, and lower body, both with an angular pyramidal, cylidrical and spherical geometric armature. Just as some of the works of Picasso and Braque of the period are virtually indistinguishable, so too are Csaky's and Lipchitz sculptures, only Csaky's predates that of Lipchitz by three years.[37]

Like Archipenko and Csaky, both Lipchitz and Henri Laurens were aware of primitive African art, though hardly evident in their works. Lipchitz collected African art from 1912 on, but Laurens, in fact, appears to have been entirely unaffected by African art. Both his early reliefs and three-dimensional sculptures attach problems posed by Cubist painters first. Lipchitz and Laurens were concerned with giving tangible substance to idea first pronounced by Jean Metzinger in his 1910 Note sur la peinture[38] of simultaneous multiple views. "They were", as Goldwater notes, "undoubtedly impressed with the natural three-dimensionality of African sculpture and with its rhythmic interplay of solid and related void. But in its frontality and mass, though often composed of cubic shapes, it was anything but cubist, and was indeed, fundamentally anti-cubist in conception".[39] The African sculptor, writes Goldwater, "whether his forms were rectangular, elliptical, or round in outline, and whether he cut back little or much into the cylinder of fresh wood with which he began, was content to show one aspect of his figure at a time". Goldwater continues: :"He achieved his "instinctive" three-dimensional effect by calculated simplification and separation of parts that allowed the eye to grasp each one as a unified, coherent mass. The cubist sculptor, on the other hand, wished to "make his figure turn" by simultaneously showing or suggesting frontal and orthogonal planes, by flattening diagonals, and by swinging other hidden surfaces into view."[39]

Henri Laurens

%2C_p_53.jpg)

Some time after Joseph Csaky's 1911-14 sculptural figures consisting of conic, cylindrical and spherical shapes, a translation of two-dimensional form into three-dimensional form had been undertaken by the French sculptor Henri Laurens. He had met Braque in 1911 and exhibited at the Salon de la Section d'Or in 1912, but his mature activity as a sculptor began in 1915 after experimenting with different materials.[5]

Umberto Boccioni

Umberto Boccioni exhibited his Futurist sculptures in Paris in 1913 after having studied the works of Archipenko, Brâncuși, Csaky, and Duchamp-Villon. Boccioni's background was in painting, as his Futurist colleagues, but unlike others was impelled to adapt the subjects and atmospheric faceting of Futurism to sculpture.[1] For Boccioni, physical motion is relative, in opposition with absolute motion. The Futurist had no intention of abstracting reality. "We are not against nature," wrote Boccioni, "as believed by the innocent late bloomers [retardataires] of realism and naturalism, but against art, that is, against immobility."[16][40] While common in painting, this was rather new in sculpture. Boccioni expressed in the preface of the catalogue for the First Exhibition of Futurist Sculpture his wish to break down the stasis of sculpture by the utilization of diverse materials and coloring grey and black paint of the edges of the contour (to represent chiaroscuro). Though Boccioni had attacked Medardo Rosso for adhering closely to pictorial concepts, Lipchitz described Boccioni's 'Unique Forms' as a relief concept, just as a futurist painting translated into three-dimensions.[1]

Constantin Brâncuși

The works of Constantin Brâncuși differ considerably from others through lack of severe planar faceting often associated with those of prototypical Cubists such as Archipenko, Csaky and Duchamp-Villon (themselves already very different from one another). However, in common is the tendency toward simplification and abstract representation.

Before reviewing the works of Brâncuși, Arthur Jerome Eddy writes of Wilhelm Lehmbruck:

- "The two female figures exhibited by Lehmbruck, were simply decorative elongations of natural forms. In technic they were quite conventional. Their modeling was along purely classical lines, far more severely classical than much of the realistic work of Rodin."

The heads by Brâncuși were idealistic in the extreme; the sculptor carried his theories of mass and form so far he deliberately lost all resemblance to actuality. He uses his subjects as motives rather than models. In this respect he is not unlike—though more extreme than—the great Japanese and Chinese artists, who use life and nature arbitrarily to secure the results they desire.

I have a golden bronze head—a "Sleeping Muse," by Brâncuși—so simple, so severe in its beauty, it might have come from the Orient.

Of this head and two other pieces of sculpture exhibited by Brâncuși in July, 1913, at the Allied Artists' Exhibition in London, Roger Fry said in The Nation, August 2: Constantin Brâncuși's sculptures have not, I think, been seen before in England. His three heads are the most remarkable works of sculpture at the Albert Hall. Two are in brass and one in stone. They show a technical skill which is almost disquieting, a skill which might lead him, in default of any overpowering imaginative purpose, to become a brilliant pasticheur. But it seemed to me there was evidence of passionate conviction; that the simplification of forms was no mere exercise in plastic design, but a real interpretation of the rhythm of life. These abstract vivid forms into which he compresses his heads give a vivid presentment of character; they are not empty abstractions, but filled with a content which has been clearly, and passionately apprehended.[15]

Eddy elaborates on Brâncuși and Archipenko:

- "It is when we come to the work of Brâncuși and Archipenko that we find the most startling examples of the reaction along purely creative lines.

Nature is purposely left far behind, as far behind as in Cubist pictures, and for very much the same reasons.

Of all the sculpture in the International Exhibition Armory Show the two pieces that excited the most ridicule were Brâncuși's egg-shaped Portrait of Mlle. Pogany and Family Life by Archipenko.

Both are creative works, products of the imagination, but in their inspiration they are fundamentally different.[15]

By World War I

%2C_marble.jpg)

In June 1915 the young modern sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska lost his life in the war. Shortly before his death he wrote a letter and sent it to friends in London:

I have been fighting for two months and I can now gage the intensity of life.[...]

It would be folly to seek artistic emotions amid these little works of ours.[...]

My views on sculpture remain absolutely the same.

It is the vortex of will, of decision, that begins.

I shall derive my emotions solely from the arrangement of surfaces. I shall present my emotions by the arrangement of my surfaces, the planes and lines by which they are defined.

Just as this hill, where the Germans are solidly entrenched, gives me a nasty feeling, solely because its gentle slopes are broken up by earthworks, which throw long shadows at sunset—just so shall I get feeling, of whatsoever definition, from a statue according to its slopes, varied to infinity.

I have made an experiment. Two days ago I pinched from an enemy a mauser rifle. Its heavy, unwieldy shape swamped me with a powerful image of brutality.

I was in doubt for a long time whether it pleased or displeased me.

I found that I did not like it.

I broke the butt off and with my knife I carved in it a design, through which I tried to express a gentler order of feeling, which I preferred.

But I will emphasize that my design got its effect (just as the gun had) from a very simple composition of lines and planes. (Gaudier-Brzeska, 1915)[15]

Experimentation in three-dimensional art had brought sculpture into the world of painting, with unique pictorial solutions. By 1914 it was clear that sculpture had moved inexorably closer to painting, becoming a formal experiment, one inseparable from the other.[1]

By the early 1920s, significant Cubist sculpture had been done in Sweden (by sculptor Bror Hjorth), in Prague (by Gutfreund and his collaborator Emil Filla), and at least two dedicated "Cubo-Futurist" sculptors were on staff at the Soviet art school Vkhutemas in Moscow (Boris Korolev and Vera Mukhina).

The movement had run its course by about 1925, but Cubist approaches to sculpture didn't end as much as they became a pervasive influence, fundamental to the related developments of Constructivism, Purism, Futurism, Die Brücke, De Stijl, Dada, Abstract art, Surrealism and Art Deco.

Artists associated with Cubist Sculpture

- August Agero

- Alexander Archipenko

- Jean Arp

- Umberto Boccioni

- Antoine Bourdelle

- István Beöthy

- Constantin Brâncuși

- Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

- Joseph Csaky

- Andrew Dasburg

- André Derain

- Emil Filla

- Naum Gabo

- Pablo Gargallo

- Paul Gauguin

- Alberto Giacometti

- Julio González

- Otto Gutfreund

- Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

- Jean Lambert-Rucki

- Henri Laurens

- Wilhelm Lehmbruck

- Jacques Lipchitz

- Jan et Joël Martel

- Henri Matisse

- Gustave Miklos

- Amedeo Modigliani

- László Moholy-Nagy

- Henry Moore

- Chana Orloff

- Antoine Pevsner

- Pablo Picasso

- Auguste Rodin

- Edwin Scharff

- Raymond Duchamp-Villon

- William Wauer

- Ossip Zadkine

Gallery

Paul Gauguin, Soyez amoureuses vous serez heureuses, relief, 97 × 75 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Paul Gauguin, Soyez amoureuses vous serez heureuses, relief, 97 × 75 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Antoine Bourdelle, 1910–12, La Musique, bas-relief, Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, Paris

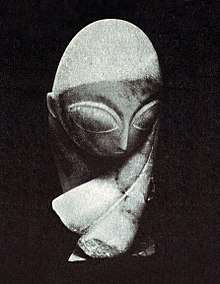

Antoine Bourdelle, 1910–12, La Musique, bas-relief, Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, Paris Constantin Brâncuși, 1912, Portrait of Mlle Pogany, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia. Armory Show postcard

Constantin Brâncuși, 1912, Portrait of Mlle Pogany, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia. Armory Show postcard%2C_now_lost._Armory_Show%2C_published_press_clipping%2C_1913.jpg) Constantin Brâncuși, 1909, Portrait De Femme (La Baronne Renée Frachon), now lost. Exhibited at 1913 Armory Show, published press clipping

Constantin Brâncuși, 1909, Portrait De Femme (La Baronne Renée Frachon), now lost. Exhibited at 1913 Armory Show, published press clipping._Armory_Show_postcard.jpg) Constantin Brâncuși, Une Muse, 1912, plaster, 45.7 cm (18 in.) Armory Show postcard. Exhibited: New York, Armory of the 69th Infantry (no. 618); The Art Institute of Chicago (no. 26) and Boston, Copley Hall (no. 8), International Exhibition of Modern Art, February–May 1913

Constantin Brâncuși, Une Muse, 1912, plaster, 45.7 cm (18 in.) Armory Show postcard. Exhibited: New York, Armory of the 69th Infantry (no. 618); The Art Institute of Chicago (no. 26) and Boston, Copley Hall (no. 8), International Exhibition of Modern Art, February–May 1913._Reproduced_in_Archipenko-Album%2C_1921..jpg) Alexander Archipenko, 1910, Le baiser (The Kiss)

Alexander Archipenko, 1910, Le baiser (The Kiss) Alexander Archipenko, Portrait de Mme Kameneff

Alexander Archipenko, Portrait de Mme Kameneff Alexander Archipenko, 1912, Dancers (Dance) (Der Tanz), 24 in. original plaster. This first version of Dancers was illustrated on the front cover of The Sketch, 29 October 1913, London

Alexander Archipenko, 1912, Dancers (Dance) (Der Tanz), 24 in. original plaster. This first version of Dancers was illustrated on the front cover of The Sketch, 29 October 1913, London Alexander Archipenko, 1912, Le Repos, Armory Show postcard published in 1913

Alexander Archipenko, 1912, Le Repos, Armory Show postcard published in 1913 August Agero, c.1911-12, Jeune fille à la rose, wood sculpture, Exposició d'Art Cubista, Galeries Dalmau, Barcelona, 1912, catalogue

August Agero, c.1911-12, Jeune fille à la rose, wood sculpture, Exposició d'Art Cubista, Galeries Dalmau, Barcelona, 1912, catalogue Amedeo Modigliani, c.1912, Female Head

Amedeo Modigliani, c.1912, Female Head%2C_location_unknown%2C_destroyed.jpg) Umberto Boccioni, 1913, Synthèse du dynamisme humain (Synthesis of Human Dynamism), sculpture destroyed

Umberto Boccioni, 1913, Synthèse du dynamisme humain (Synthesis of Human Dynamism), sculpture destroyed%2C_terracotta%2C_Armory_Show_postcard%2C_published_1913.jpg) Raymond Duchamp-Villon, 1910, Torse de jeune homme (Torso of a young man), terracotta, Armory Show postcard, published 1913

Raymond Duchamp-Villon, 1910, Torse de jeune homme (Torso of a young man), terracotta, Armory Show postcard, published 1913 Raymond Duchamp-Villon, 1913, Le chat (The Cat), Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris

Raymond Duchamp-Villon, 1913, Le chat (The Cat), Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris- Raymond Duchamp-Villon, 1913, Les amants II, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris

%2C_photograph_by_Duchamp-Villon.jpg) Raymond Duchamp-Villon, 1914, Femme assise, plaster, 65.5 cm (25.75 in), photograph by Duchamp-Villon

Raymond Duchamp-Villon, 1914, Femme assise, plaster, 65.5 cm (25.75 in), photograph by Duchamp-Villon_limestone%2C_60_cm%2C_Kr%C3%B6ller-M%C3%BCller_Museum%2C_Otterlo%2C_Holland.tiff.jpg) Joseph Csaky, ca 1920, Tête (front and side view), limestone, 60 cm, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, the Netherlands

Joseph Csaky, ca 1920, Tête (front and side view), limestone, 60 cm, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, the Netherlands Joseph Csaky, 1920, Deux figures, relief, limestone, polychrome, 80 cm, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, the Netherlands

Joseph Csaky, 1920, Deux figures, relief, limestone, polychrome, 80 cm, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, the Netherlands Edwin Scharff, Großer Schreitender Mann (Man of the Border), sculpture, before 1920

Edwin Scharff, Großer Schreitender Mann (Man of the Border), sculpture, before 1920

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Penelope Curtis (1999). Sculpture 1900-1945: After Rodin. Oxford University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-19-284228-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Christopher Green, 2009, Cubism, Origins and application of the term, MoMA, Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press

- ↑ Guillaume Apollinaire; Dorothea Eimert; Anatoli Podoksik (2010). Cubism. Parkstone International. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-84484-749-5.

- ↑ Grace Glueck, Picasso Revolutionized Sculpture Too, NY Times, exhibition review 1982 Retrieved July 20, 2010

- 1 2 3 George Heard Hamilton (1993). Painting and Sculpture in Europe: 1880-1940. YALE University Press. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-300-05649-5.

- 1 2 Raymond Duchamp-Villon, 1876-1918. 1967.

- 1 2 3 4 Douglas Cooper (1971). The Cubist Epoch. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 11–221, 231–232. ISBN 978-0-7148-1448-3.

- ↑ The Guardian, Hillary Spurling on The Back Series

- ↑ MoMA, the collection

- ↑ Tate

- ↑ Peter Collins (1998-07-14). Changing Ideals in Modern Architecture, 1750-1950. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-7735-6705-4.

- 1 2 Mark Antliff, Patricia Dee Leighten, Cubism and Culture, Thames & Hudson, 2001

- ↑ Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes, Du "Cubisme", Edition Figuière, Paris, 1912 (First English edition: Cubism, Unwin, London, 1913. In Robert L. Herbert, Modern Artists on Art, Englewood Cliffs, 1964.

- ↑ John Adkins Richardson, Modern Art and Scientific Thought, Chapter Five, Cubism and Logic, University of Chicago Press, 1971, pp. 104-127

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Arthur Jerome Eddy, Cubists and Post-Impressionism, A.C. McClurg & Co., Chicago, 1914, second edition 1919

- 1 2 Alexandre Thibault, La durée picturale chez les cubistes et futuristes comme conception du monde : suggestion d'une parenté avec le problème de la temporalité en philosophie, Faculté des Lettres Université Laval, Québec, 2006

- ↑ Rodin Museum, The Three Shades

- ↑ Alex Mittelmann, State of the Modern Art World, The Essence of Cubism and its Evolution in Time, 2011

- ↑ Musée d'Orsay, Paul Gauguin, Oviri

- 1 2 Erle Loran (1963). Cézannes̓ Composition: Analysis of His Form with Diagrams and Photographs of His Motifs. University of California Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-520-00768-0.

- ↑ Joann Moser, 1985, Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, Pre-Cubist Works, 1904-1909, The University of Iowa Museum of Art, J. Paul Getty Trust, University of Washington Press, pp. 34, 35

- ↑ Victoria Charles (2011). Pablo Picasso. Parkstone International. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-78042-299-2.

- ↑ Anatoli Podoksik; Victoria Charles (2011). Pablo Picasso. Parkstone International. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-78042-285-5.

- ↑ Solomon-Godeau, Abigail, Going Native: Paul Gauguin and the Invention of Primitivist Modernism, in The Expanded Discourse: Feminism and Art History, N. Broude and M. Garrard (Eds.). New York: Harper Collins, 1986, p. 314.

- 1 2 Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, The Rise of Cubism, The documents of modern art; Wittenborn, Schultz, translated by Henry Aronson, notice by Robert Motherwell, New York, 1949. First published under the title Der Weg zum Kubismus, in 1920

- ↑ Robert Rosenblum, "Cubism," Readings in Art History 2 (1976), Seuphor, Sculpture of this Century

- 1 2 3 4 5 Edith Balas (1998). Joseph Csáky: A Pioneer of Modern Sculpture. American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87169-230-6.

- ↑ Herbert Read, A Concise History of Modern Sculpture, Praeger, 1964

- 1 2 Alfred Hamilton Barr (1936). Cubism and abstract art: painting, sculpture, constructions, photography, architecture, industrial art, theatre, films, posters, typography. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-17935-6.

- 1 2 3 Alexandra Keiser (Archipenko Foundation/Courtauld Institute of Art), Photographic reproductions of Sculpture: Archipenko and Cultural Exchange, Henry Moore Institute, 12 November 2010

- ↑ Herwarth Walden, Einblick in Kunst: Expressionismus, Futurismus, Kubismus. Berlin: Der Sturm, 1917

- ↑ Félix Marcilhac, Joseph Csaky, Une Vie - Une Oeuvre, 23 Nov. - 21 Dec. 2007, exhibit catalogue, Galerie Félix Marcilhac

- 1 2 3 Marcilhac, Félix, 2007, Joseph Csaky, Du cubisme historique à la figuration réaliste, catalogue raisonné des sculptures, Les Editions de l'Amateur, Paris

- ↑ Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, Histoire & Mesure, no. XXII -1 (2007), Guerre et statistiques, L'art de la mesure, Le Salon d'Automne (1903-1914), l'avant-garde, ses étranger et la nation française (The Art of Measure: The Salon d'Automne Exhibition (1903-1914), the Avant-Garde, its Foreigners and the French Nation), electronic distribution Caim for Éditions de l'EHESS (in French)

- ↑ Guillaume Apollinaire, Aesthetic Meditations On Painting, The Cubist Painters (1913), Second Series, translated and published in The Little Review, Miscellany Number, Quarterly Journal of Art and Letters, Winter 1922

- ↑ Jacques Lipchitz; Alan G. Wilkinson (1987). Jacques Lipchitz: The Cubist Period, 1913-1930 : [exhibition] October 15 - November 14, 1987, Marlborough Gallery. Marlborough Gallery.

- ↑ Joseph Csaky, 1913, Figure de Femme Debout (Figure Habillée), vs. Jacques Lipchitz, 1916, Baigneuse Assise

- ↑ Jean Metzinger, Note sur la peinture (Note on painting), Pan, Paris, October–November 1910, 649-51

- 1 2 Robert Goldwater (1986). Primitivism in Modern Art:. Harvard University Press. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-674-70490-9.

- ↑ Umberto Boccioni, Dynamisme plastique : peinture et sculpture futuriste, Lausanne, L'Age d'homme, 1975

Further reading

- Apollinaire, Guillaume, 1912, Art and Curiosity, the Beginning of Cubism, Le Temps

- Canudo, Ricciotto, 1914, Montjoie, text by André Salmon, 3rd issue, 18 March

- Reveredy, Pierre, 1917, Sur le Cubisme, Nord-Sud (Paris), March 15, 5-7

- Apollinaire, Guillaume, Chroniques d'art, 1902–1918

- Balas, Edith, 1981, The Art of Egypt as Modigliani's Stylistic Source, Gazette des Beaux-Arts

- Krauss, Rosalind E., Passages in Modern Sculpture, MIT Press, 1981