Contemporary Latin

Contemporary Latin is the form of the Latin language used from the end of the 19th century through the present. Various kinds of contemporary Latin can be distinguished. On the one hand there is its survival in areas such as taxonomy as the result of the widespread presence of the language in the New Latin era. This is usually found in the form of mere words or phrases used in the general context of other languages. On the other hand, there is the use of Latin as a language in its own right as a full-fledged means of expression. Living or Spoken Latin, being the most specific development of Latin in the contemporary context, is the primary subject of this article.

| Contemporary Latin | |

|---|---|

| Latinas viva | |

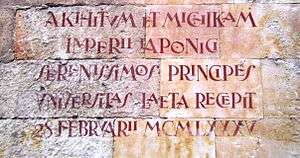

A contemporary Latin inscription at Salamanca University commemorating the visit of the then Prince Akihito and Princess Michiko of Japan in 1985 (MCMLXXXV). | |

| Region | Europe |

| Era | Developed from Neo Latin between 19th and 20th centuries |

|

Indo-European

| |

Early form | |

| Latin alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

la |

| ISO 639-2 |

lat |

| ISO 639-3 |

lat |

| Glottolog | None |

Token Latin

As a relic of the great importance of New Latin as the formerly dominant international lingua franca down to the 19th century in a great number of fields, Latin is still present in words or phrases used in many languages around the world, and some minor communities use Latin in their speech.

Mottos

The official use of Latin in previous eras has survived at a symbolic level in many mottos that are still being used and even coined in Latin to this day. Old mottos like E pluribus unum, found in 1776 on the Seal of the United States, along with Annuit cœptis and Novus ordo seclorum, and adopted by an Act of Congress in 1782, are still in use. Similarly, current pound sterling coins are minted with the Latin inscription ELIZABETH·II·D·G·REG·F·D (Dei Gratia Regina, Fidei Defensor, i.e. Queen by the Grace of God, Defender of the Faith). The official motto of the multilingual European Union, adopted as recently as 2000, is the Latin In varietate concordia. Similarly, the motto on the Canadian Victoria Cross is in Latin, perhaps due to Canada's bilingual status.

Fixed phrases

Some common phrases that are still in use in many languages have remained fixed in Latin, like the well-known dramatis personæ or habeas corpus.

In science

In fields as varied as mathematics, physics, astronomy, medicine, pharmacy, and biology,[1] Latin still provides internationally accepted names of concepts, forces, objects, and organisms in the natural world.

The most prominent retention of Latin occurs in the classification of living organisms and the binomial nomenclature devised by Carolus Linnæus, although the rules of nomenclature used today allow the construction of names which may deviate considerably from historical norms.

Another continuation is the use of Latin names for the constellations and celestial objects (used in the Bayer designations of stars), as well as planets and satellites, whose surface features have been given Latin selenographic toponyms since the 17th century.

Symbols for many of those chemical elements of the periodic table known in ancient times reflect and echo their Latin names, like Au for aurum (gold) and Fe for ferrum (iron).

Vernacular vocabulary

Latin has also contributed a vocabulary for specialised fields such as anatomy and law which has become part of the normal, non-technical vocabulary of various European languages. Latin continues to be used to form international scientific vocabulary and classical compounds. Separately, more than 56% of the vocabulary used in English today derives ultimately from Latin, either directly (28.24%) or through French (28.30%).[2]

Ecclesiastical Latin

The Catholic Church has continued to use Latin. Two main areas can be distinguished. One is its use for the official version of all documents issued by Vatican City, which has remained intact to the present. Although documents are first drafted in various vernaculars (mostly Italian, now also German), the official version is written in Latin by the Latin Letters Office. The other is its use for the liturgy, which has diminished after the Second Vatican Council of 1962–65, but seems to have recently seen some resurgence, sponsored in part by Pope Benedict XVI.

After the Church of England published the Book of Common Prayer in English in 1559, a 1560 Latin edition was published for use at universities such as Oxford and the leading public schools, where the liturgy was still permitted to be conducted in Latin,[3] and there have been several Latin translations since. Most recently a Latin edition of the 1979 USA Anglican Book of Common Prayer has appeared.[4]

Academic Latin

Latin has also survived to some extent in the context of classical scholarship. Some classical periodicals, like Mnemosyne and the German Hermes, to this day accept articles in Latin for publication.[5]

Latin is used in most of the introductions to the critical editions of ancient authors in the Oxford Classical Texts series, and it is also nearly always used for the apparatus criticus of Ancient Greek and Latin texts.

The University Orator at the University of Cambridge makes a speech in Latin marking the achievements of each of the honorands at the annual Honorary Degree Congregations, as does the Public Orator at the Encaenia ceremony at the University of Oxford. Harvard and Princeton also have Latin Salutatory commencement addresses every year.[6]

The Charles University in Prague[7] and many other universities around the world conduct the awarding of their doctoral degrees in Latin. Other universities and other schools issue diplomas written in Latin.

In addition to the above, Brown, Sewanee, and Bard College also hold in Latin a portion of their graduation ceremonies.

The famous song Gaudeamus igitur is acknowledged as the anthem of academia and is sung at university opening or graduation ceremonies throughout Europe.

Living Latin

Living Latin (Latinitas viva in Latin itself), also known as Spoken Latin, is an effort to revive Latin as a spoken language and as the vehicle for contemporary communication and publication. Involvement in this Latin revival can be a mere hobby or extend to more serious projects for restoring its former role as an international auxiliary language.

Origins

After the decline of Latin at the end of the New Latin era started to be perceived, there were attempts to counteract the decline and to revitalize the use of Latin for international communication.

In 1815, Miguel Olmo wrote a booklet proposing Latin as the common language for Europe, with the title Otia Villaudricensia ad octo magnos principes qui Vindobonæ anno MDCCCXV pacem orbis sanxerunt, de lingua Latina et civitate Latina fundanda liber singularis ("Leisure of Villaudric to the eight great princes who ordained world peace at Vienna in 1815, an extraordinary book about the Latin language and a Latin state to be founded").[8]

In the late 19th century, Latin periodicals advocating the revived use of Latin as an international language started to appear. Between 1889 and 1895, Karl Heinrich Ulrichs published in Italy his Alaudæ.[9] This publication was followed by the Vox Urbis: de litteris et bonis artibus commentarius,[10] published by the architect and engineer Aristide Leonori from 1898, twice a month, until 1913, one year before the outbreak of World War I.

The early 20th century, marked by warfare and by drastic social and technological changes, saw few advances in the use of Latin outside academia. Following the beginnings of the re-integration of postwar Europe, however, Latin revivalism gained some strength.

One of its main promoters was the former dean of the University of Nancy (France), Prof. Jean Capelle, who in 1952 published a cornerstone article called "Latin or Babel"[11] in which he proposed Latin as an international spoken language.

Capelle was called "the soul of the movement" when in 1956 the first International Conference for Living Latin (Congrès international pour le Latin vivant) took place in Avignon,[12] marking the beginning of a new era of the active use of Latin. About 200 participants from 22 different countries took part in that foundational conference.

Pronunciation

The essentials of the classical pronunciation had been defined since the early 19th century (e.g. in K.L. Schneider's Elementarlehre der Lateinischen Sprache, 1819), but in many countries there was strong resistance to adopting it in instruction. In English-speaking countries, where the traditional academic pronunciation diverged most markedly from the restored classical model, the struggle between the two pronunciations lasted for the entire 19th century. The transition between Latin pronunciations was long drawn out;[13] in 1907 the "new pronunciation" was officially recommended by the Board of Education for adoption in schools in England.[14][15]

Although the older pronunciation, as found in the nomenclature and terminology of various professions, continued to be used for several decades, and in some spheres prevails to the present day, contemporary Latin as used by the living Latin community has generally adopted the classical pronunciation of Latin as restored by specialists in Latin historical phonology.[16]

A similar shift occurred in German-speaking areas: the traditional pronunciation is discussed in Deutsche Aussprache des Lateinischen (in German), while the reconstructed classical pronunciation, which took hold around 1900, is discussed at Schulaussprache des Lateinischen.

Aims

Many users of contemporary Latin promote its use as a spoken language, a movement that dubs itself "Living Latin". Two main aims can be distinguished in this movement:

For Latin instruction

Among the proponents of spoken Latin, some promote the active use of the language to make learning Latin both more enjoyable and more efficient, drawing upon the methodologies of instructors of modern languages.

In the United Kingdom, the Association for the Reform of Latin Teaching (ARLT, still existing as the Association for Latin Teaching), was founded in 1913 by the distinguished classical scholar W. H. D. Rouse. It arose from summer schools which Rouse organised to train Latin teachers in the direct method of language teaching, which entailed using the language in everyday situations rather than merely learning grammar and syntax by rote. The Classical Association also encourages this approach. The Cambridge University Press has now published a series of school textbooks based on the adventures of a mouse called Minimus, designed to help children of primary school age to learn the language, as well as its well-known Cambridge Latin Course (CLC) to teach the language to secondary school students, all of which include extensive use of dialogue and an approach to language teaching mirroring that now used for most modern languages, which have brought many of the principles espoused by Rouse and the ARLT into the mainstream of Latin teaching.

Outside Great Britain, one of the most accomplished handbooks that fully adopts the direct method for Latin is the well-known Lingua Latina per se illustrata by the Dane Hans Henning Ørberg, first published in 1955 and improved in 1990. It is composed fully in Latin, and requires no other language of instruction, and it can be used to teach pupils whatever their mother tongue.

For contemporary communication

Others support the revival of Latin as a language of international communication, in the academic, and perhaps even the scientific and diplomatic, spheres (as it was in Europe and European colonies through Middle Ages until the mid-18th century), or as an international auxiliary language to be used by anyone. However, as a language native to no people, this movement has not received support from any government, national or supranational.

Supporting institutions and publications

A substantial group of institutions (particularly in Europe, but also in North and South America) has emerged to support the use of Latin as a spoken language.[17]

The foundational first International Conference for living Latin (Congrès international pour le Latin vivant) that took place in Avignon was followed by at least five others.[18] As a result of those first conferences, the Academia Latinitati Fovendae was then created in Rome. Among its most prominent members are well-known classicists from all over the world,[19] like Prof. Michael von Albrecht or Prof. Kurt Smolak. The ALF held its first international conference in Rome in 1966 bringing together about 500 participants. From then on conferences have taken place every four or five years, in Bucharest, Malta, Dakar, Erfurt, Berlin, Madrid, and many other places. The official language of the ALF is Latin and all acts and proceedings take place in Latin.

Also in the year 1966 Clément Desessard published a method with tapes within the series sans peine of the French company Assimil. Desessard's work aimed at teaching contemporary Latin for use in an everyday context, although the audio was often criticized for being recorded with a thick French accent. Assimil took this out of print at the end of 2007 and published another Latin method which focused on the classical idiom only. However, in 2015 Assimil re-published Desessard's edition with new audio CDs in restored classical Latin pronunciation. Desessard's method is still used for living Latin instruction at the Schola Latina Universalis.

In 1986 the Belgian radiologist Gaius Licoppe, who had discovered the contemporary use of Latin and learnt how to speak it thanks to Desessard's method, founded in Brussels the Fundatio Melissa for the promotion of Latin teaching and use for communication.[20]

In Germany, Marius Alexa and Inga Pessarra-Grimm founded in September 1987 the Latinitati Vivæ Provehendæ Associatio (LVPA, or Association for the Promotion of Living Latin).[21]

The first Septimana Latina Amoeneburgensis (Amöneburg Latin Week) was organized in 1989 at Amöneburg, near Marburg in Germany, by Mechtild Hofmann and Robert Maier. Since then the Latin Weeks were offered every year. In addition, members of the supporting association Septimanae Latinae Europaeae (European Latin Weeks) published a text book named Piper Salve that contains dialogues in modern everyday Latin.[22]

At the Accademia Vivarium Novum located in Rome, Italy, all classes are taught by faculty fluent in Latin or Ancient Greek, and resident students speak in Latin or Greek at all times outside class. Most students are supported by scholarships from the Mnemosyne foundation and spend one or two years in residence to acquire fluency in Latin.[23] The living Latin movement eventually crossed the Atlantic, where it continues to grow. In the summer of 1996, at the University of Kentucky, Prof. Terence Tunberg established the first Conventiculum, an immersion conference in which participants from all over the world meet annually to exercise the active use of Latin to discuss books and literature, and topics related to everyday life.[24] The success of the Conventiculum Lexintoniense has inspired similar conferences throughout the United States.

In October 1996 the Septentrionale Americanum Latinitatis Vivæ Institutum (SALVI, or North American Institute for Living Latin Studies) was founded in Los Angeles, by a group of professors and students of Latin literature concerned about the long-term future of classical studies in the US.[25]

In the University of Kentucky, Prof. Terence Tunberg founded the Institutum Studiis Latinis Provehendis (known in English as the Institute of Latin Studies), which awards Graduate Certificates in Latin Studies addressed at those with a special interest gaining "a thorough command of the Latin language in reading, writing and speaking, along with a wide exposure to the cultural riches of the Latin tradition in its totality".[26] This is the only degree-conferring program in the world with courses taught entirely in Latin.

There is also a proliferation of Latin-speaking institutions, groups and conferences in the Iberian Peninsula and in Latin America. Some prominent examples of this tendency towards the active use of Latin within Spanish and Portuguese-speaking countries are the annual conferences called Jornadas de Culturaclasica.com, held in different cities of southern Spain, as well as the CAELVM (Cursus Aestivus Latinitatis Vivae Matritensis), a Latin summer program in Madrid. In 2012, the Studium Angelopolitanum was founded in Puebla, Mexico, by Prof. Alexis Hellmer, in order to promote the study of Latin in that country, where only one university grants a degree in Classics.

Most of these groups and institutions organise seminars and conferences where Latin is used as a spoken language, both throughout the year and over the summer, in Europe and in America.[27]

Less academic summer encounters wholly carried out in Latin are the ones known as Septimanæ Latinæ Europææ (European Latin Weeks), celebrated in Germany and attracting people of various ages from all over Europe.[22]

At the present time, several periodicals and social networking web sites are published in Latin. In France, immediately after the conference at Avignon, the publisher Théodore Aubanel launched the magazine Vita Latina, which still exists, associated to the CERCAM (Centre d'Étude et de Recherche sur les Civilisations Antiques de la Méditerranée) of the Paul Valéry University, Montpellier III. Until very recently, it was published in Latin in its entirety.[28] In Germany, the magazine Vox Latina was founded in 1965 by Caelestis Eichenseer (1924–2008) and is to this day published wholly in Latin four times a year in the University of Saarbrücken.[29] In Belgium, the magazine Melissa created in 1984 by Gaius Licoppe is still published six times a year completely in Latin.[30]

Hebdomada aenigmatum[31] is a free online magazine of crosswords, quizzes, and other games in Latin language. It is published by the Italian cultural Association Leonardo in collaboration with the online Latin news magazine Ephemeris[32] and with ELI publishing house.

The Finnish radio station YLE Radio 1 has for many years broadcast a now famous weekly review of world news called Nuntii Latini completely in Latin.[33] The German Radio Bremen also had regular broadcasts in Latin (till December 2017).[34] Other attempts have been less successful.[35] Beginning from July 2015 Radio F.R.E.I. from Erfurt (Germany) broadcasts in Latin once a week on Wednesdays for 15 minutes; the broadcast is called Erfordia Latina.[36]

In 2015 the Italian startup pptArt launched its catalogue (Catalogus)[37] and its registration form for artists (Specimen ad nomina signanda)[38] in Latin and English.

In 2016 ACEM (Enel executives' cultural association) organized with Luca Desiata and Daniel Gallagher the first Business Latin course for managers (Congressus studiorum – Lingua Latina mercatoria).[39][40]

The government of Finland, during its presidencies of the European Union, issued official newsletters in Latin on top of the official languages of the Union.[41]

On the Internet

The emergence of the Internet on a global scale in the 1990s provided a great tool for the flourishing of communication in Latin, and in February 1996[42] a Polish Latinist from Warsaw (Poland), Konrad M. Kokoszkiewicz, founded what is still today the most populated and successful Latin-only email list on the Internet, the Grex Latine Loquentium. Subsequently, the Nuntii Latini of YLE Radio 1 would also create a discussion list called YLE Colloquia Latina.[43] The Circulus Latinus Panormitanus of Palermo (Italy) went a step further creating the first online chat in Latin called the Locutorium.[44]

In February 2003 Konrad M. Kokoszkiewicz published an on-line glossary with his proposals for some computer terms in Latin under the title of Vocabula computatralia.[45] The Internet also allows for the preservation of other contemporary Latin dictionaries that have fallen out of print or have never been printed, like the Latinitas Recens (Speculum)[46] or the Adumbratio Lexici Angli et Latini.[47]

In June 2004[48] an on-line newspaper Ephemeris was founded once again from Warsaw by Stanisław Tekieli, and is to this day published wholly in Latin about current affairs.[49]

In January 2008 a Schola, (membership 1800) a Latin-only social network service, including a real-time video and/or text chatroom, was founded from London (UK).[50]

A number of Latin web portals, websites, and blogs in Latin have developed, like Lingua Latina Æterna from Russia[51] or Verba et facta from somewhere in the US.[52]

The Internet also provides tools like Latin spell checkers[53] for contemporary Latin writers, or scansion tools[54] for contemporary Latin poets.

Some websites, such as Google and Facebook, provide Latin as a language option.

There is a MUD text game in Latin called Labyrinthus Latinus aimed at uniting people interested in the language. The website is shut down but the game is still available at labyrinthus.latinus.imp.ch:3333. In addition, the video games Minecraft, OpenTTD, and The Battle for Wesnoth provide Latin as a language option.

There is even a Latin Wikipedia, although discussions are held not only in Latin but in German, English, and other languages as well. Nearly 200 active editors work on the project. There are nearly 100,000 articles on topics ranging from ancient Rome to mathematics, Tolkien's fiction, and geography. Those in particularly good Latin, currently about 10% of the whole, are marked.[55]

In public spaces

Although less so than in previous eras, contemporary Latin has also been used for public notices in public spaces:

The Wallsend Metro station of the Tyne and Wear Metro has signs in Latin.

The Vatican City has an automated teller machine with instructions in Latin.[56]

Original production

Some contemporary works have been produced originally in Latin, most overwhelmingly poetry,[57] but also prose, as well as music or cinema. They include:

Poetry

- 1924. Carminum libri quattuor by Tomás Viñas.[58]

- 1946. Carmina Latina by A. Pinto de Carvalho.[59]

- 1954. Vox Humana by Johannes Alexander Gaertner.[60]

- 1962. Pegasus Tolutarius by Henry C. Snurr aka C. Arrius Nurus.

- 1966. Suaviloquia by Jan Novák.

- 1966. Cantus Firmus by Johannes Alexander Gaertner.[60]

- 1972. Carmina by Traian Lăzărescu.[61]

- 1991. Periegesis Amatoria by Geneviève Immè.

- 1992. Harmonica vitrea by Anna Elissa Radke.

Prose

- 1948. Graecarum Litterarum Historia by Antonio d'Elia.[62]

- 1952. Latinarum Litterarum Historia by Antonio d'Elia.[63]

- 1961. De sacerdotibus sacerdotiisque Alexandri Magni et Lagidarum eponymis by Jozef IJsewijn.[64]

- 1965. Sententiæ by Alain van Dievoet (pen name: Alaenus Divutius).

- 1966. Mystagogus Lycius, sive de historia linguaque Lyciorum by Wolfgang Jenniges.[65]

- 2011. Capti: Fabula Menippeo-Hoffmanniana Americana by Stephen A. Berard (pen name: Stephanus Berard).[66][67]

Music

- 1927. Oedipus Rex by Igor Stravinsky (an opera-oratorio with libretto, based on Sophocles's tragedy, prepared in French by Jean Cocteau and given its final Latin form by Abbé Jean Daniélou).

- 1994. Ista?!?! by Latin hip hop band Ista.

- 2011. Audio, Video, Disco by French electronic group Justice.

Cinema

- 1976. Sebastiane by Derek Jarman and Paul Humfress.[68]

- 2004. The Passion of the Christ by Mel Gibson.[69]

- 2009. Pacifica by Samohi Latin Media (SLAM).

- 2010. Barnabus & Bella by SLAM.

Television

T-shirts

A T-shirt with the rhyming motto Multi Frigent, Pauci Rigent, "Many are Cold but Few are Frozen" for the fictional University of Antarctica, with a penguin seal, by artist Janice Bender. The motto's translation puns the Christian motto, "Many are Called but Few are Chosen."

Translations

Various texts—usually children's books—have been translated into Latin since the beginning of the living Latin movement in the early fifties for various purposes, including use as a teaching tool or simply to demonstrate the capability of Latin as a means of expression in a popular context. They include:

- 1884. Rebilius Cruso[72] (Robinson Crusoe) tr. Francis William Newman.

- 1922. Insula Thesavraria (Treasure Island) tr. Arcadius Avellanus.

- 1928. Vita discriminaque Robinsonis Crusoei (Robinson Crusoe) tr. Arcadius Avellanus.

- 1960. Winnie Ille Pu (Winnie-the-Pooh) tr. Alexander Lenard.

- 1962. Ferdinandus Taurus (Ferdinand the Bull) tr. Elizabeth Chamberlayne Hadas.

- 1962. Fabula De Petro Cuniculo (Tale of Peter Rabbit) tr. E. Perot Walker.

- 1964. Alicia in Terra Mirabili (Alice's Adventures in Wonderland) tr. Clive Harcourt Carruthers.

- 1965. Fabula de Jemima Anate-Aquatica (The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck) tr. Jonathan Musgrave.

- 1966. Aliciae per Speculum Transitus (Quaeque ibi Invenit) (Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There) tr. Clive Harcourt Carruthers.

- 1973–present. Asterix[73] (Asterix – a French comic book series)

- 1978. Fabula de Domino Ieremia Piscatore (The Tale of Jeremy Fisher) tr. E. Perot Walker.

- 1983. Alix – Spartaci Filius (Alix – Franco-Belgian comics)

- 1985. Regulus, vel Pueri Soli Sapiunt (The Little Prince) tr. Augusto Haury

- 1987. De Titini et Miluli Facinoribus: De Insula Nigra (Tintin – Franco-Belgian comics)

- 1987. The Classical Wizard / Magus Mirabilis in Oz (The Wonderful Wizard of Oz) tr. C.J. Hinke and George Van Buren.

- 1990. De Titini et Miluli Facinoribus: De Sigaris Pharaonis (Tintin – Franco-Belgian comics)

- 1991. Tela Charlottae (Charlotte's Web) tr. Bernice Fox.

- 1994. Sub rota (Unterm Rad) tr. Sigrides C. Albert

- 1998. Quomodo Invidiosulus Nomine Grinchus Christi Natalem Abrogaverit (How the Grinch Stole Christmas) tr. Jennifer Morrish Tunberg, Terence O. Tunberg.

- 1998. Winnie Ille Pu Semper Ludet (The House at Pooh Corner) tr. Brian Staples.

- 2000. Cattus Petasatus (The Cat in the Hat) tr. Jennifer Morish Tunberg, Terence O. Tunberg.

- 2002. Arbor Alma (The Giving Tree) tr. Terence O. Tunberg, Jennifer Morrish Tunberg.

- 2003. Virent Ova, Viret Perna (Green Eggs and Ham) tr. Terence O. Tunberg, Jennifer Morrish Tunberg.

- 2003. Harrius Potter et Philosophi Lapis (Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone) tr. Peter Needham.

- 2005. Tres Mures Caeci (The Three Blind Mice) tr. David C. Noe.

- 2006. Harrius Potter et Camera Secretorum (Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets) tr. Peter Needham.

- 2007. Olivia: the essential Latin edition tr. Amy High.

- 2009. Over 265 illustrated children's books in Latin have been published on the Tar Heel Reader website.

- 2009. Murena, Murex et aurum (Murena, La pourpre et l'or) tr. Claude Aziza and Cathy Rousset.

- 2009. Mundo Novo[74] – adaptation of A Whole New World from Disney's Aladdin

- 2012. Hobbitus Ille (The Hobbit) tr. Mark Walker.

Dictionaries, glossaries, and phrase books for contemporary Latin

- 1990. Latin for All Occasions, a book by Henry Beard, attempts to find Latin equivalents for contemporary catchphrases.

- 1992–97. Neues Latein Lexicon / Lexicon recentis Latinitatis by Karl Egger, containing more than 15,000 words for contemporary everyday life.

- 1998. Imaginum vocabularium Latinum by Sigrid Albert.

- 1999. Piper Salve by Robert Maier, Mechtild Hofmann, Klaus Sallmann, Sabine Mahr, Sascha Trageser, Dominika Rauscher, Thomas Gölzhäuser.

- 2010. Visuelles Wörterbuch Latein-Deutsch by Dorling Kindersley, translated by Robert Maier.

- 2012. Septimana Latina vol. 1+2 edited by Mechtild Hofmann and Robert Maier (based on Piper Salve).

See also

| Latin edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Library resources about Contemporary Latin |

Notes and references

- ↑ Yancey, P.H. (March 1944). "Introduction to Biological Latin and Greek". Bios. 15 (1): 3–14. JSTOR 4604798.

- ↑ According to the computerised survey of about 80,000 words in the old Shorter Oxford Dictionary (3rd ed.) published in Ordered Profusion by Thomas Finkenstaedt and Dieter Wolff, Latin influence in English.

- ↑ "Liber Precum Publicarum – The Book of Common Prayer in Latin (1560)". Justus.anglican.org. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "Liber Precum Publicarum: the 1979 US Book of Common Prayer in Latin". Justus.anglican.org. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ Konrad M. Kokoszkiewicz, "A. Gellius, Noctes Atticæ, 16.2.6: tamquam si te dicas adulterum negent", Mnemosyne 58 (2005) 132–135; "Et futura panda siue de Catulli carmine sexto corrigendo", Hermes 132 (2004) 125–128.

- ↑ "Harvard's Latin Salutatory Address 2007". YouTube. 12 June 2007. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- ↑ IJsewijn, Jozef, Companion to Neo-Latin Studies. Part I. History and Diffusion of Neo-Latin Literature, Leuven University Press, 1990, p. 112s.

- ↑ Cf. Wilfried Stroh (ed.), Alaudæ. Eine lateinische Zeitschrift 1889–1895 herausgegeben von Karl Heinrich Ulrichs. Nachdruck mit einer Einleitung von Wilfried Stroh, Hamburg, MännerschwarmSkript Verlag, 2004.

- ↑ Cf. Volfgangus Jenniges, "Vox Urbis (1898–1913) quid sibi proposuerit", Melissa, 139 (2007) 8–11.

- ↑ Published on 23 October 1952 in the French Bulletin de l'Éducation Nationale, an English version of the same was published in The Classical Journal and signed by himself and Thomas H. Quigley (The Classical Journal, Vol. 49, No. 1, October 1953, pp. 37–40)

- ↑ Goodwin B. Beach, "The Congress for Living Latin: Another View", The Classical Journal, Vol. 53, No. 3, December 1957, pp. 119–122:

- ↑ F. Brittain (1934). Latin in Church (first ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 60.

- ↑ "Recommendations of the Classical Association on the Teaching of Latin". Forgottenbooks.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ↑ The School World: A Monthly Magazine of Educational Work and Progress. 9. Macmillan & Co. 1907.

- ↑ E.g. Prof. Edgar H. Sturtevant (The Pronunciation of Greek and Latin, Chicago Ares Publishers Inc. 1940) and Prof. W. Sidney Allen (Vox Latina, A Guide to the Pronunciation of Classical Latin, Cambridge University Press 1965), who followed in the tradition of previous pronunciation reformers; cf. Erasmus's De recta Latini Græcique sermonis pronuntiatione dialogus and even Alcuin's De orthographia.

- ↑ "Vincula – Circulus Latínus Londiniénsis". Circuluslatinuslondiniensis.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ The fifth conference took place in Pau, France, from the 1st to 5 April 1975.

- ↑ "Academia Latinitati Fovendae - SODALES". Web.archive.org. 11 October 2006. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ↑ "MELISSA sodalitas perenni Latinitati dicata". Fundatiomelissa.org. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "Pagina domestica – L.V.P.A. e.V". Lvpa.de. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- 1 2 Robert Maier. "Septimanae Latinae Europaeae". Septimanalatina.org. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 November 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- ↑ "Conventiculum Latinum | Modern & Classical Languages, Literatures & Cultures". Mcl.as.uky.edu. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "About Us | SALVI: Septentrionale Americanum Latinitatis Vivae Institutum". Latin.org. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "Graduate Certificate in Latin Studies – Institute for Latin Studies | Modern & Classical Languages, Literatures & Cultures". Mcl.as.uky.edu. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 January 2009. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- ↑ "UPVM | Accueil". Recherche.univ-montp3.fr (in French). Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "Vox latina". Voxlatina.uni-saarland.de. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 June 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ↑ "HEBDOMADA AENIGMATUM: The first magazine of Latin crosswords". Mylatinlover.it. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "EPHEMERIS. Nuntii Latini universi". Alcuinus.net. 27 April 2009. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "Nuntii Latini | Radio | Areena". Yle.fi. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "Radio Cicero funkt nicht mehr - Finito". Radiobremen.de. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ↑ "Radio Zammù, Università di Catania". Radiozammu.it. 21 July 2007. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "Radio F.R.E.I. Programm". Radiofrei.de. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ Archived 7 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Archived 7 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Murzio, Antonio (22 June 2016), "L'ingegnere che si diverte con le parole latine", La Stampa

- ↑ "EPHEMERIS. Nuntii Latini universi". Ephemeris.alcuinus.net. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- ↑ "Victorius Ciarrocchi: De Grege Latine loquentium deque linguae Latinae praestantia". Alcuinus.net. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 March 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 January 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ↑ "Vocabula computatralia". Obta.uw.edu.pl. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "Latinitas Recens (Speculum)". Latinlexicon.org. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 April 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ "Ephemeris". Ephemeris.alcuinus.net. 26 June 2004. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "EPHEMERIS. Nuntii Latini universi". Ephemeris.alcuinus.net. 27 April 2009. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ Archived 30 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Lingua Latina Aeterna :: Latin – a living language | Lingua Latina Aeterna". Linguaeterna.com. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "Verba et Facta". Nemo-nusquam.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "COL – Latin Spellchecker (Microsoft Windows)". Latin.drouizig.org. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "latin poetry / text-to-speech". Poetaexmachina.net. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ As of August 2013, there are 94,777 pages, of which about a third are marked as stubs. Among the pages whose Latin has been assessed, 9,658 are marked as having good Latin and just over 500 are marked as poor Latin.

- ↑ "Photographic image of ATM" (JPG). Farm3.static.flickr.com. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "Contemporary Latin Poetry". Suberic.net.

- ↑ IJsewijn, Jozef, Companion to Neo-Latin Studies. Part I. History and Diffusion of Neo-Latin Literature, Leuven University Press, 1990, p. 113.

- ↑ IJsewijn, Jozef, Companion to Neo-Latin Studies. Part I. History and Diffusion of Neo-Latin Literature, Leuven University Press, 1990, p. 123.

- 1 2 IJsewijn, Jozef, Companion to Neo-Latin Studies. Part I. History and Diffusion of Neo-Latin Literature, Leuven University Press, 1990, p. 293.

- ↑ IJsewijn, Jozef, Companion to Neo-Latin Studies. Part I. History and Diffusion of Neo-Latin Literature, Leuven University Press, 1990, p. 226.

- ↑ Institution login (1 January 2009). "Graecarum Litterarum Historia. By Antonius D'elia S. J.Rome: Angelo signorelli, 1948. Pp.328, with eleven plates and index of writers mentioned. Price: Lire 600. | Greece & Rome | Cambridge Core". Cambridge.org. doi:10.1017/S0017383500010688. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ Antonii D'Elia (March 1956). "Review: Latinarum litterarum historia". The Classical Journal. The Classical Association of the Middle West and South, Inc. (CAMWS). 51: 289–290.

- ↑ IJsewijn, Jozef, Companion to Neo-Latin Studies. Part I. History and Diffusion of Neo-Latin Literature, Leuven University Press, 1990, p. 156.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 28 December 2009.

- ↑ "CAPTI and the Sphinx Heptology by Stephen Berard". Boreoccidentales.com. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ Albert Baca (5 March 2012). "Capti: Fabula Menippeo-Hoffmanniana Americana (Latin Edition): Stephani Berard: 9781456759735: Amazon.com: Books". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ Sebastiane on IMDb

- ↑ The Passion of the Christ on IMDb

- ↑ ""Kulturzeit extra: O Tempora!" – 3sat.Mediathek". 3sat.de. 19 December 2011. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "Kulturzeit O Tempora Making Of". YouTube. 2 March 2009. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "Rebilius Cruso: Robinson Crusoe, in Latin: a book to lighten tedium to a learner: Defoe, Daniel, 1661?–1731: Free Download & Streaming: Internet Archive". Archive.org. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ "Asterix around the World – the many Languages of Asterix". Asterix-obelix.nl. 13 April 2017. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ↑ TranslatorCarminum (28 July 2009). "Disney's Aladdin – A Whole New World (Latin fandub)" – via YouTube.

Further reading

English

- W. H. S. Jones, M.A. Via Nova or The Application of the Direct Method to Latin and Greek, Cambridge University Press 1915.

- Jozef IJzewijn, A companion to neo-Latin studies, 1977.

Spanish

- José Juan del Col, ¿Latín hoy?, published by the Instituto Superior Juan XXIII, Bahía Blanca, Argentina, 1998 ("Microsoft Word - LATINHOY.doc" (PDF). Juan23.edu.ar. Retrieved 2017-07-10. )

French

- Guy Licoppe, Pourquoi le latin aujourd'hui ?: (Cur adhuc discenda sit lingua Latina), s.l., 1989

- Françoise Waquet, Le latin ou l'empire d'un signe, XVIe–XXe siècle, Paris, Albin Michel, 1998.

- Guy Licoppe, Le latin et le politique: les avatars du latin à travers les âges, Brussels, 2003.

German

- Wilfried Stroh, Latein ist tot, es lebe Latein!: Kleine Geschichte einer großen Sprache ( ISBN 9783471788295)