Coffee culture

Coffee culture describes a social atmosphere or series of associated social behaviors that depends heavily upon coffee, particularly as a social lubricant. The term also refers to the diffusion and adoption of coffee as a widely consumed stimulant by a culture. In the late 20th century, particularly in the Western world and urbanized centers around the globe, espresso has been an increasingly dominant form.

The formation of culture around coffee and coffeehouses dates back to 14th century Turkey. Coffeehouses in Western Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean were traditionally social hubs, as well as artistic and intellectual centers. For example, Les Deux Magots in Paris, now a popular tourist attraction, was once associated with the intellectuals Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. In the late 17th and 18th centuries, coffeehouses in London became popular meeting places for artists, writers and socialites, and were also the center for much political and commercial activity. Elements of today's coffeehouses (slower paced gourmet service, tastefully decorated environments, or social outlets such as open mic nights) have their origins in early coffeehouses, and continue to form part of the concept of coffee culture.

In the United States in particular, the term is frequently used to designate the ubiquitous presence of hundreds of espresso stands and coffee shops in the Seattle metropolitan area and the spread of franchises of businesses such as Starbucks and their clones across the United States. Other aspects of coffee culture include the presence of free wireless Internet access for customers, many of whom do business in these locations for hours on a regular basis. The style of coffee culture varies by country, with an example being the strength of existing cafe style coffee culture in Australia used to explain the poor performance of Starbucks there.[1]

In many urban centers in the world, it is not unusual to see several espresso shops and stands within walking distance of each other or on opposite corners of the same intersection, typically with customers overflowing into parking lots. Thus, the term coffee culture is also used frequently in popular and business media to describe the deep impact of the market penetration of coffee-serving establishments.

Coffeehouses

A "coffeehouse or "café" is an establishment which primarily serves prepared coffee or other hot drinks. Historically cafés have been an important social gathering point in Europe. They were—and continue to be—venues where people gather to talk, write, read, entertain one another, or pass the time. During the 16th-century coffeehouses were banned in Mecca because they attracted political gatherings.

In 2016, Albania surpassed Spain by becoming the country with the most coffee houses per capita in the world.[2] In fact, there are 654 coffee houses per 100,000 inhabitants in Albania, a country with only 2.5 million inhabitants.

Café culture in China has grown rapidly over the years - Shanghai alone has an estimated 6,500 coffee houses currently. This includes small chains and large corporations like Starbucks.[3]

In addition to coffee, many cafés also serve tea, sandwiches, pastries, and other light refreshments. Some provide other services, such as wired or wireless internet access (thus the name, "internet café" — which has carried over to stores that provide internet service without any coffee) for their customers.

Social aspects

Many social aspects of coffee can be seen in the modern-day lifestyle. By absolute volume, the United States is the largest market for coffee, followed by Germany and Japan. Canada, Australia, Sweden and New Zealand are the other large coffee consuming countries. Tim Hortons is Canada's largest coffee chain, making millions of cups of coffee a day.[4] The Nordic countries consume the most coffee per capita, with Finland typically occupying the top spot with a per-capita consumption with 12 kg per year, followed by Norway, Iceland and Denmark.[5][4] Consumption has also vastly increased in recent years in the traditionally tea-drinking United Kingdom, but as of 2005 it was still below 5 kg per year. Turkish coffee is popular in Turkey, the Eastern Mediterranean, and southeastern Europe.

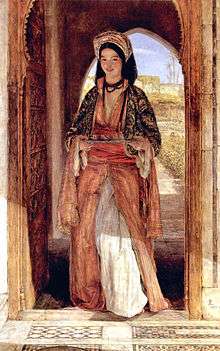

Coffeehouse culture has a high penetration in much of the former Ottoman Empire, where Turkish coffee remains the dominant style of preparation. The coffee enjoyed in the Ottoman Middle East was produced in Yemen/Ethiopia and despite multiple attempts to ban the substance for its stimulating qualities, by 1600 coffee and coffeehouses were a prominent feature of Ottoman life.[6] Various scholarly perspectives on the functions of the Ottoman coffeehouse exist. Many of these perspectives argue that Ottoman coffeehouse were centers of important social ritual, making them as, or more important, than the coffee itself.[7] "At the start of the modern age, the coffee houses were places for renegotiating the social hierarchy and for challenging the social order".

Coffee has also been important in Austrian and in French culture since the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Vienna's coffeehouses are prominent in Viennese culture and known internationally, while Paris was important in the development of "café society" in the first half of the 20th century.

In some countries, notably in Northern Europe, coffee parties are a popular form of entertainment. Besides coffee, the host or hostess at the coffee party also serves cake and pastries, sometimes homemade. In Germany, Netherlands, Austria and the Nordic countries, strong black coffee is also regularly drunk along with or immediately after main meals such as lunch and dinner, and several times at work or school. In the café culture of these countries, especially Germany and Sweden, free refills of black coffee are often provided at restaurants and cafés, especially if customers have also bought a sweet treat or pastry with the coffee.

Coffee plays a large role in much of history and literature because of the large effects the coffee industry has had on cultures where it is produced or consumed. Coffee is often mentioned as one of the main economic goods used in imperial control of trade, and with colonized trade patterns in "goods" such as slaves, coffee, and sugar, which defined Brazilian trade, for example, for centuries. Coffee in culture or trade is a central theme and prominently referenced in much poetry, fiction, and regional history.

Coffee utensils

- Coffee grinder

- Coffee pot, for brewing with hot water, made of glass or metal.

- Coffeemaker

- Coffee cup, for drinking coffee, usually smaller than a teacup in North America and Europe. There are many different kinds of coffee cups.

- A saucer is placed under the coffee cup.

- Coffee spoon, usually small and used to stir in the cup.

- Coffee service tray, to place the coffee utensils on and to keep the hot water from spilling onto the table.

- Coffee canister, usually airtight, for storing coffee.

- Water kettle, or coffee kettle, to heat the water.

- Sugar bowl, for granular sugar or sugar lumps or cubes.

- Cream pitcher or jug, also called a creamer, for fresh milk or cream.

Coffee break

A coffee break (or "fika", as it's commonly referred to in Sweden) is a routine social gathering for a snack and short downtime practiced by employees in business and industry. The coffee break allegedly originated in the late 19th century in Stoughton, Wisconsin, with the wives of Norwegian immigrants. The city celebrates this every year with the Stoughton Coffee Break Festival.[8] In 1951, Time noted that "[s]ince the war, the coffee break has been written into union contracts".[9] The term subsequently became popular through a Pan-American Coffee Bureau ad campaign of 1952 which urged consumers, "Give yourself a Coffee-Break — and Get What Coffee Gives to You."[10] John B. Watson, a behavioral psychologist who worked with Maxwell House later in his career, helped to popularize coffee breaks within the American culture.[11]

Coffee breaks usually last from 10 to 20 minutes and frequently occur at the end of the first third of the work shift. In some companies and some civil service, the coffee break may be observed formally at a set hour. In some places, a "cart" with hot and cold beverages and cakes, breads and pastries arrives at the same time morning and afternoon, an employer may contract with an outside caterer for daily service, or coffee breaks may take place away from the actual work-area in a designated cafeteria or tea room.

By country

Albania

In 2016, Albania surpassed Spain by becoming the country with the most coffee houses per capita in the world.[12] In fact, there are 654 coffee houses per 100,000 inhabitants in Albania, a country with only 2.5 million inhabitants. This is due to coffe houses closing down in Spain due to the economic crisis, and the fact that as many cafes open as they close in Albania. In addition, the fact that it was one of the easiest ways to make a living after the fall of communism in Albania, together with the country’s Ottoman legacy further reinforce the strong dominance of coffee culture in Albania.

Esperantujo

In Esperanto Culture, a gufujo (plural gufujoj) is a non-alcoholic, non-smoking, makeshift, European-style café that takes place in the evening or at night. Esperanto speakers meet at a specified location, either a rented space or someone's house, and enjoy live music or reading aloud while having tea, coffee, pastries, etc. There may be payment with money expected as in an actual café. It is a calm affair in direct contrast to the wild parties that other Esperanto speakers might be having elsewhere at the same time. Gufujoj were originally intended for people who dislike crowds, loud noise, and partying.

Italy

In Italy locals drink coffee at the counter as opposed to asking it to go, serve espresso as the default coffee, don't flavor espresso, and don't drink cappuccinos after 11 AM.[13]

Sweden

_%26_family_c_1916.jpg)

Swedes have fika (Swedish pronunciation: [²fiːka]), meaning "coffee break", often with pastries,[14] although coffee can be substituted with tea or even juice, lemonade or squash for children. A sandwich, fruit or a small meal may be called fika as the English concept of afternoon tea.[15] The tradition has spread through Swedish businesses around the world.[16] Fika is a social institution in Sweden and the practice of taking a break with a beverage and a snack is widely accepted as central to Swedish life.[17] As a common mid-morning and mid-afternoon practice at workplaces in Sweden, fika may also function partially as an informal meeting between co-workers and management people, and it can even be considered impolite not to join everyone else for fika.[18] [19]

Education and research

An American college-level course entitled "Design of Coffee" is part of the chemical engineering curriculum at University of California, Davis.[20] A research facility devoted to coffee research was under development on the UC Davis campus in early 2017.[20]

In media

Coffee culture frequently shows up in comics, television, and movies in a variety of ways. TV shows such as NCIS show characters constantly with espresso in hand or people distributing take-out cups to other characters. The comic strips Adam and Pearls Before Swine frequently center the strip around visiting or working at coffee shops.

Daily Mail writer Philip Nolan stated that the spread of the coffee culture in Ireland is largely accredited to American television shows Friends and Frasier, saying, "We saw it reflected in the lifestyles of our TV favorites the Friends gang in Central Perk drinking coffee instead of alcohol; Frasier and Niles having latte and biscotti in the [Café] Nervosa; every cop on TV being called out on a 911 just as he ambled back to his car with Dunkin' Donuts and a cup of strong, black coffee."[21]

See also

References

- ↑ Berg, Chris (2008-08-03). "Memo Starbucks: next time try selling ice to Eskimos". The Age. Melbourne.

- ↑ http://www.monitor.al/rekordi-shqiperia-kalon-e-para-ne-bote-per-numrin-e-larte-te-bar-kafeve-per-banor/

- ↑ Jourdan, Adam; Baertlein, Lisa. "China's budding coffee culture propels Starbucks, attracts rivals". Reuters. Reuters. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- 1 2 "International Coffee Organization - Historical Data". Ico.org. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

- ↑ ""Coffee Consumption Per Capita Worldwide"". IndexMundi Blog. Retrieved 2010-05-13.

- ↑ Baram, Uzi (1999). "Clay tobacco pipes and coffee cup sherds in the archaeology of the Middle East: Artifacts of social tensions from the Ottoman past". International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 3: 137–151.

- ↑ Mikhail, Alan (2014). The heart’s desire: Gender, urban space and the Ottoman coffee house. Ottoman Tulips, Ottoman Coffee: Leisure and Lifestyle in the Eighteenth Century ed. Dana Sajdi. London: Tauris Academic Studies. pp. 133–170.

- ↑ "Stoughton, WI - Where the Coffee Break Originated". www.stoughtonwi.com. Stoughton, Wisconsin Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on 2009-05-20. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

Mr. Osmund Gunderson decided to ask the Norwegian wives, who lived just up the hill from his warehouse, if they would come and help him sort the tobacco. The women agreed, as long as they could have a break in the morning and another in the afternoon, to go home and tend to their chores. Of course, this also meant they were free to have a cup of coffee from the pot that was always hot on the stove. Mr. Gunderson agreed and with this simple habit, the coffee break was born.

- ↑ Time. 1951-03-05. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "The Coffee break". npr.org. 2002-12-02. Retrieved 2009-06-10.

Wherever the coffee break originated, Stamberg says, it may not actually have been called a coffee break until 1952. That year, a Pan-American Coffee Bureau ad campaign urged consumers, 'Give yourself a Coffee-Break -- and Get What Coffee Gives to You.'

- ↑

Hunt, Morton M. (1993). The story of psychology (1st ed.). New York: Doubleday. p. 260. ISBN 0-385-24762-1.

[work] for Maxwell House that helped make the 'coffee break' an American custom in offices, factories, and homes.

- ↑ http://www.ocnal.com/2018/02/albania-ranked-first-in-world-for.html

- ↑ Santoro, Paola (22 April 2016). "Your Cheat Sheet To Italian Coffee Culture". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- ↑ Henderson, Helene (2005). The Swedish Table. U of Minnesota P. p. xxiii-xxv. ISBN 978-0-8166-4513-8.

- ↑ {{Cite book |last=Johansson Robinowitz |first=Christina |author2=Lisa Werner Carr |title=Modern-day Vikings: a practical guide to interacting with the Swedes |publisher=Intercultural Press |year=2001 |page=149 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MAn641nHfrYC&pg=PA149 |isbn=978-1-877864-88-9}}

- ↑ {{Cite web|url=http://www.bbc.com/capital/story/20160112-in-sweden-you-have-to-stop-work-to-chat|title=Is this the sweet secret to Swedish success?|last=Hotson|first=Elizabeth|access-date=2017-02-02|publisher = BBC}}

- ↑ {{Cite web|url=https://sweden.se/culture-traditions/fika/|title=Fika | sweden.se|date=2014-05-08|website=sweden.se|language=en-US|access-date=2016-05-21}}

- ↑ Paulsen, Roland (2014) Empty Labor: Idleness and Workplace Resistance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 9781107066410; p. 90

- ↑ {{Cite book |last1=Goldstein |first1=Darra |first2=Kathrin |last2=Merkle |title=Culinary cultures of Europe: identity, diversity and dialogue |publisher=Council of Europe |year=2005 |pages=428–29 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1Dz0srxxDFoC&pg=PA429 |isbn=978-92-871-5744-7}}

- 1 2 Barber, Gregory (February 2017). "Brewmaster Bill: Inside the Coffee Lab". Alpha. WIRED (Magazine). p. 18.

- ↑ Nolan, Philip. "Will Our Love Affair With Coffee Survive the 3 Latte?; As the Price of Your Grande Skinny Soars." Daily Mail [London]. 24 Aug 2006. LexisNexis Academic. LexisNexis. U. of Nevada, Reno, Getchell Lib. 5 Feb 2008. <http://www.lexisnexis.com>