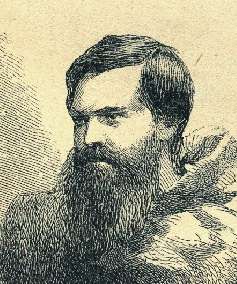

Charles Francis Hall

Charles Francis Hall (1821 – November 8, 1871) was an American Arctic explorer, best known for the suspicious circumstances surrounding his death while leading the American-sponsored Polaris expedition in an attempt to be the first to reach the North Pole. The expedition was marred by insubordination, incompetence, and poor leadership.

Hall returned to the ship from an exploratory sledging journey, and promptly fell ill. Before he died, he accused members of the crew of poisoning him. An exhumation of his body in 1968 revealed that he had ingested a large quantity of arsenic in the last two weeks of his life.

Early life

Little is known of Hall's early life. He was born in the state of Vermont, but while he was still a child his family moved to Rochester, New Hampshire, where, as a boy, he was apprenticed to a blacksmith. In the 1840s he married and drifted westward, arriving in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1849. There he went into business making seals and engraving plates, and later began to publish two small newspapers, The Cincinnati Occasional and The Daily Press.[1]

First Arctic Expedition

Around 1857, Hall became interested in the Arctic and spent the next few years studying the reports of previous explorers and trying to raise money for an expedition, primarily intended to learn the fate of Sir John Franklin's lost expedition.

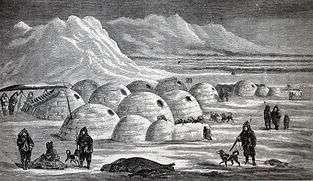

In 1860, Hall began his first expedition (1860–63), gaining passage out of New Bedford on the whaler George Henry under Captain Sidney O. Budington, whose uncle James Budington had salvaged Edward Belcher's exploration ship HMS Resolute, also on the "George Henry". He got as far as Baffin Island, where the George Henry was forced to winter over.[1] The Inuit told Hall of surviving relics from Martin Frobisher's mining venture at Frobisher Bay on Baffin Island. Hall soon travelled there to see them first-hand, drawing upon the inestimable assistance of his newly found Inuit guides Ebierbing ("Joe") and Tookoolito ("Hannah").

Hall also learned what he interpreted as evidence that some members of Franklin's lost expedition might still be alive. On his return to New York, Hall arranged for Harper Brothers to publish his account of the expedition Arctic Researches and Life Among the Esquimaux. It was edited by a British mariner and writer William Parker Snow, who was also obsessed with the fate of Franklin. The two men eventually fell out (largely because Parker Snow was very slow editing the manuscript), and amongst other things Parker Snow later claimed Hall had used his ideas for the search for Franklin without giving him due credit.

Second Arctic Expedition

During 1863 Hall planned a second expedition to seek more clues on the fate of Franklin, including efforts to find any of the rumoured survivors or their written records. The first attempt using the 95-ton schooner Active was abandoned, probably due to lack of finances caused by the American Civil War and a troubled relationship with his intended second-in-command Parker Snow. Finally, in July 1864, a much smaller expedition departed in the whaler Monticello.

During this second expedition (1864–69) to King William Island, he found remains and artifacts from the Franklin expedition, and made more inquiries about their fate from natives living there. Hall eventually realized that the stories of survivors were unreliable, either by the Inuit or his own readiness to give them overly optimistic interpretations. He also became disillusioned with the Inuit by the discovery that the remnants of Franklin's expedition had deliberately been left to starve. He failed to consider that it would have been impossible for the local population to support such a large group of supernumeraries.[2]

Polaris expedition

Hall's third expedition was of an entirely different character. He received a grant of $50,000 from the U.S. Congress to command an expedition to the North Pole in the ship Polaris. The party of 25 also included Hall's old friend Budington as sailing master, George Tyson as navigator, and Dr. Emil Bessels, a German physician and naturalist, as chief of the scientific staff. The expedition was troubled from the start as the party split into rival factions. Hall's authority over the expedition was resented by a large portion of the party, and discipline broke down.

Polaris sailed into Thank God Harbor (now called Hall Bay) on September 10, 1871, and achored for the winter on the shore of northern Greenland. That fall, upon returning to the ship from a sledging expedition with an Inuit guide, Hall suddenly fell ill after drinking a cup of coffee. He collapsed in what was described as a fit. For the next week he suffered from vomiting and delirium, then seemed to improve for a few days. At that time, he accused several of the ship's company, including Dr. Bessels, of having poisoned him. Shortly after, Hall began suffering the same symptoms, and died on November 8. Hall was taken ashore and given a formal burial.

Command of the expedition devolved on Budington, who reorganized to try for the Pole in June 1872. This was unsuccessful and Polaris turned south. On October 12, the ship was beset by ice in Smith Sound and was on the verge of being crushed. Nineteen of the crew and the Inuit guides abandoned ship for the surrounding ice while 14 remained aboard. Polaris was run aground near Etah and crushed on October 24. After wintering ashore, the crew sailed south in two boats and were rescued by a whaler, returning home via Scotland.

The following year, the remainder of the party attempted to extricate Polaris from the pack and head south. A group, including Tyson, became separated as the pack broke up violently and threatened to crush the ship in the fall of 1872. The group of 19 drifted on an ice floe for the next six months over 1,500 miles (2,414 km) before being rescued off the coast of Newfoundland by the sealer Tigress on April 30, 1873, and probably would have all perished had the group not included several Inuit who were able to hunt for the party.

Investigation

The official investigation that followed ruled that Hall had died from apoplexy. However, in 1968, Hall's biographer Chauncey C. Loomis, a professor at Dartmouth College, made an expedition to Greenland to exhume Hall's body. To the benefit of the professor, permafrost had preserved the body, flag shroud, clothing and coffin. Tests on tissue samples of bone, fingernails and hair showed that Hall died of poisoning from large doses of arsenic in the last two weeks of his life. This diagnosis is consistent with the symptoms party members reported. It is possible that Hall treated himself with the poison, as arsenic was a common ingredient of quack medicines of the time. Loomis considered it possible that he was murdered by one of the other members of the expedition, possibly Dr. Bessels, though no charges were ever filed. Most recently, the emergence of affectionate letters written by both Hall and Bessels to Vinnie Ream, a young sculptor they both met in New York while waiting for the Polaris to be outfitted, has suggested a further motive for Bessels to have been the killer.[3]

References

- 1 2 Mowat 1973.

- ↑ Russell Potter, transcript for the NOVA programme "Arctic Passage," PBS.org

- ↑ Bessels 2016, pp. 537–42.

Bibliography

- Berton, Pierre (1988). The Arctic Grail: The Quest for the North West Passage and the North Pole. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-670-82491-5.

- Bessels, Emil (2016). Polaris: The Chief Scientist's Recollections of the American North Pole Expedition. Calgary: University of Calgary Press. ISBN 978-1-552-38875-4.

- Hall, Charles Francis (1865). Arctic Researches, and Life Among the Esquimaux. New York: Harper & Brothers. ISBN 978-0-659-98930-7.

- Henderson, Bruce B. (2001). Fatal North: Adventure and Survival Aboard USS Polaris. New York: New American Library. ISBN 978-0-451-40935-5.

- Mowat, Farley (1973). The Polar Passion: The Quest for the North Pole. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-771-06621-4.