Chanak Crisis

| Chanak Crisis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Turkish War of Independence | |||||||

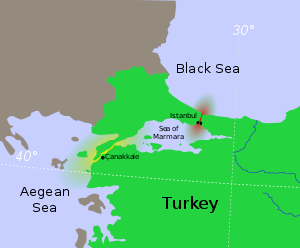

Locations of Turkish Straits; the Bosphorus (red), the Dardanelles (yellow) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| Occupation Force | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~3 divisions |

All Allied forces in Istanbul and Çanakkale [1] Total: ~51,300 soldiers (411 machine guns, 57 artillery pieces) (French and Italian Forces withdrew as soon as the ultimatum was delivered.) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None | None | ||||||

The Chanak Crisis (Turkish: Çanakkale Krizi), also called the Chanak Affair and the Chanak Incident, was a war scare in September 1922 between the United Kingdom and Turkey (the Grand National Assembly). Chanak refers to Çanakkale, a city at the Anatolian side of the Dardanelles Strait. The crises was caused by Turkish efforts to push the Greek armies out of Turkey and restore Turkish rule in the Allied occupied territories of Turkey, primarily in Constantinople (now Istanbul) and Eastern Thrace. Turkish troops marched against British and French positions in the Dardanelles neutral zone. For a time, war between Britain and Turkey seemed possible, but Canada refused to agree as did France and Italy. British public opinion did not want a war. The British military did not either, and the top general on the scene refused to relay an ultimatum to the Turks because he counted on a negotiated settlement. The Conservatives in Britain's coalition government refused to follow Liberal Prime Minister David Lloyd George, who with Winston Churchill was calling for war.[2]

The crisis quickly ended when Turkey, having overwhelmed the Greeks, agreed to a negotiated settlement that gave it the territory it wanted. Lloyd George's mishandling of the crisis contributed to his downfall via the Carlton Club meeting. The crisis raised the issue of who decided on war for the British Empire, and was Canada's first assertion of diplomatic independence from London. Historian Robert Blake says the Chanak incident led to Arthur Balfour's definition of Britain and the dominions as "autonomous Communities within the British Empire, equal in status, in no way subordinate one to another in any aspect of the domestic or internal affairs, though united by a common allegiance to the Crown, and freely associated as members of the British Commonwealth of Nations." In 1931 the UK Parliament enacted Balfour's formula into law through the Statute of Westminster 1931.[3]

The events

The Turkish troops had recently defeated Greek forces and recaptured İzmir (Smyrna) on 9 September and were advancing on Constantinople in the neutral zone. In an interview published on Daily Mail, 15 September 1922, leader of the Turkish national movement Mustafa Kemal Atatürk stated that: "Our demands remain the same after our recent victory as they were before. We ask for Asia Minor, Thrace up to the river Maritsa and Constantinople... We must have our capital and I should in that case be obliged to march on Constantinople with my army, which will be an affair of only a few days. I much prefer to obtain possession by negotiation, though naturally I cannot wait indefinitely." [4] The British Cabinet met in the same day and decided that British forces should maintain their positions. On the following day, in the absence of Foreign Secretary Lord Curzon, certain Cabinet ministers issued a communiqué threatening Turkey with a declaration of war by Britain and the Dominions, on the grounds that Turkey had violated the Treaty of Sèvres. On 18 September, on his return to London, Curzon pointed out that this would enrage the Prime Minister of France, Raymond Poincaré, and left for Paris to attempt to smooth things over. Poincaré, however, had already ordered the withdrawal of the French detachment at Chanak but persuaded the Turks to respect the neutral zone. Curzon reached Paris on 20 September and, after several angry meetings with Poincaré, reached agreement to negotiate an armistice with the Turks.[5]

Meanwhile, the Turkish population living in Constantinople were being organised for a possible offensive against the city by the Kemalist forces. For instance, Ernest Hemingway, reporting for The Toronto Daily Star at the time as a war correspondent, wrote about a specific incident:

| “ | "Another night a destroyer... stopped a boatload of Turkish women who were crossing from Asia Minor...On being searched for arms it turned out all the women were men. They were all armed and later proved to be Kemalist officers sent over to organize the Turkish population in the suburbs in case of an attack on Constantinople"[6] | ” |

In British politics, Lloyd George, Winston Churchill, and the Conservative Lord Birkenhead were pro-Greek and wanted war; all other Conservatives of the coalition in his government were pro-Turk and rejected war. Lloyd George's position as head of the coalition became untenable.[7] Furthermore, the British public were alarmed by the Chanak episode and the possibility of going to war again. It further undercut Lloyd George that he had not fully consulted the Dominion prime ministers.

Unlike 1914, when World War I broke out, Canada in particular did not automatically consider itself active in the conflict. Instead, Prime Minister Mackenzie King insisted that the Canadian Parliament should decide on the course of action the country would follow. King was offended by the telegram he received from Churchill asking for Canada to send troops to Chanak to support Britain, and sent back a telegram, which was couched in Canadian nationalist language, declaring that Canada would not automatically support Britain if it came to war with Turkey.[8] Given that the majority of the MPs of King's Liberal Party were opposed to going to war with Turkey together with the Progressive MPs who were supporting King's minority government, it is likely that Canada would have declared neutrality if the crisis came to war. The Chanak issue badly divided Canadian public opinion with French-Canadians and Canadian nationalists in English-Canada like professor O.D. Skelton saying Canada should not issue "blank cheques" to Britain like that issued in 1914 and supporting King's implicit decision for neutrality.[8] By contrast, the Conservative leader Arthur Meighen in a speech in Toronto criticized King and declared: "When Britain's message came, then Canada should have said, 'Ready, aye ready, we stand by you.'"[9] By the time the issue had been debated in the House of Commons of Canada, the threat at Chanak had passed. Nonetheless, King made his point: the Canadian Parliament would decide the role that Canada would play in external affairs and could diverge from the British government.[10] The other dominion prime ministers and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Kingdom of Italy and the Kingdom of Romania gave no support.[5]

On 23 September, the British cabinet decided to give East Thrace to the Turks, thus forcing Greeks to abandon it without a fight. This convinced Kemal to accept the opening of armistice talks and on 28 September he told the British that he had ordered his troops to avoid any incident at Chanak, nominating Mudanya as the venue for peace negotiations. The parties met there on 3 October and agreed to the terms of the Armistice of Mudanya on 11 October, two hours before British forces were due to attack.

Consequences

Lloyd George's rashness resulted in the calling of a meeting of Conservative MPs at the Carlton Club on 19 October 1922, which passed a motion that the Conservative Party should fight the next general election as an independent party. This decision had dire ramifications for Lloyd George, as the Conservative Party made up the vast majority of the 1918–1922 post-war coalition. Indeed, they could have made up the majority government if it were not for the coalition.

Lloyd George also lost the support of the influential Curzon, who considered that the Prime Minister had been manoeuvring behind his back. Following the Carlton Club decision, the MPs voted 185 to 85 for ending the Coalition. Lloyd George resigned as Prime Minister, never to return to cabinet level politics.[11] The Conservatives, under returned party leader Bonar Law, subsequently won the general election with an overall majority.

British and French forces were ultimately withdrawn from the neutral zone in summer 1923, following the ratification of the Treaty of Lausanne.

The Chanak crisis fundamentally challenged the assumption that the Dominions would automatically follow Britain into war. The American historian Gerhard Weinberg wrote what is usually described as the "British" victory of 1918 is a misnomer as the Dominions together with India had played a disproportionate and decisive victory in helping Britain win the First World War, causing a "180-degree shift" in British-Dominion relations as now Britain was dependent upon the Dominions for military support instead of the Dominions depending on Britain.[12] Given the importance of the Dominions, it was assumed that Britain would not win another major war without the aid from the Dominions.[12] The Chanak crisis changed the relations between the Dominions and London, paving the way for the 1931 Statue of Westminster, which explicitly declared that the Dominions had the power to declare war. Weinberg wrote that Dominion-British relations were an "important, but generally neglected aspect" of the diplomacy of the 1930s.[13] In 1938, when the peace of Europe was threatened by the claim of Germany to the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia, the statements from the Dominion governments to the British government that they were not willing to go to war with Germany over the Sudetenland issue "made any decision to fight exceedingly difficult".[14] With the exception of New Zealand, none of the Dominions were willing to accept a war with Germany in 1938. The motivations of the individual Dominion prime ministers differed-with Joseph Lyons of Australia fearing a Japanese invasion if war broke out in Europe, General J. B. M. Hertzog of South Africa was a Germanophile and anti-British Afrikaner nationalist, and William Lyon Mackenzie King of Canada worried that another war with Germany would shatter Canadian national unity-but with the exception of Michael Savage of New Zealand all were opposed to war with Germany in 1938.[15] In turn, the need to bring the Dominions on Britain's side changed British policies. In the spring of 1939, when the Danzig crisis was threatening to plunge Europe into war, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth visited Canada in a royal tour that was marked by unusual lavish pomp and ceremony in a bid to influence Canadian public opinion in a pro-British direction at a time when another war seemed imminent.[16] Strikingly, the king and queen spent much time in Quebec, the most anti-British of the 9 provinces, giving speeches in French praising French-Canadians. When the king gave a speech in French in Montreal saying he had always appreciated the French-Canadians for bringing their language and culture to the British empire, the crowd roared its approval and shouted Vive le roi! ("Long live the king!"). The 1939 royal tour accomplished its purpose in creating enough pro-British sentiment, especially in French-Canada, that King felt sufficiently confident in asking Parliament for a declaration of war on Germany on 10 September 1939 without the fear of shattering Canadian national unity.[16]

References

- ↑ Zekeriya Türkmen, (2002), İstanbul'un işgali ve İşgal Dönemindeki Uygulamalar (13 Kasım 1918 – 16 Mart 1920), Atatürk Araştırma Merkezi Dergisi, XVIII (53): pages 338–339. (in Turkish)

- ↑ A. J. P. Taylor (1965). English History 1914–1945. Oxford University Press. pp. 190–92.

- ↑ Robert Blake (2013). The Decline of Power, 1915–1964. Faber & Faber. p. 68.

- ↑ ELEFTHERIA DALEZIOU, BRITAIN AND THE GREEK-TURKISH WAR AND SETTLEMENT OF 1919–1923: THE PURSUIT OF SECURITY BY 'PROXY' IN WESTERN ASIA MINOR

- 1 2 Macfie, A. L. "The Chanak Affair (September–October 1922)", Balkan Studies 1979, Vol. 20 Issue 2, pp. 309–341.

- ↑ Ernest Hemingway, Hemingway on War, p 278 Simon and Schuster, 2012 ISBN 1476716048,

- ↑ Alfred F. Havighurst (1985). Britain in Transition: The Twentieth Century. University of Chicago Press. pp. 174–75.

- 1 2 Levine, Allen William Lyon Mackenzie King : a Life Guided by the Hand of Destiny Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre, 2011 page 131.

- ↑ Levine, Allen William Lyon Mackenzie King : a Life Guided by the Hand of Destiny Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre, 2011 page 132.

- ↑ Dawson, Robert Macgregor. William Lyon Mackenzie King: 1874–1923 (1958) pp. 401–16.

- ↑ Darwin, J. G. "The Chanak Crisis and the British Cabinet", History, Feb 1980, Vol. 65 Issue 213, pp 32–48.

- 1 2 Weinberg, Gerhard "Reflections on Munich after 60 years" pages 1-12 from The Munich Crisis, 1938 edited by Igor Lukes and Erik Goldstein, London: Frank Cass, 1999 pages 6-7.

- ↑ Weinberg, Gerhard "Reflections on Munich after 60 years" pages 1-12 from The Munich Crisis, 1938 edited by Igor Lukes and Erik Goldstein, London: Frank Cass, 1999 pages 12

- ↑ Weinberg, Gerhard "Reflections on Munich after 60 years" pages 1-12 from The Munich Crisis, 1938 edited by Igor Lukes and Erik Goldstein, London: Frank Cass, 1999 page 7.

- ↑ Fry, Michael Graham "The British Dominions and the Munich Crisis" from The Munich Crisis, 1938 edited by Igor Lukes and Erik Goldstein, London: Frank Cass, 1999 pages 293-341 pages 296-304.

- 1 2 Morton, Desmond A Military History of Canada, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1999 page 179.

Further reading

- Adelson, Roger. London and the Invention of the Middle East: Money, Power, and War, 1902–1922 (1995) pp 207–11

- Darwin, J. G. "The Chanak Crisis and the British Cabinet", History (1980) 65#213 pp 32–48. online

- Ferris, John. "'Far too dangerous a gamble'? British intelligence and policy during the Chanak crisis, September–October 1922." Diplomacy and Statecraft (2003) 14#2 pp: 139–184. online

- Ferris, John. "Intelligence and diplomatic signalling during crises: The British experiences of 1877–78, 1922 and 1938." Intelligence and National Security (2006) 21#5 pp: 675–696. online

- Laird, Michael. "Wars averted: Chanak 1922, Burma 1945–47, Berlin 1948." Journal of Strategic Studies (1996) 19#3 pp: 343–364. DOI:10.1080/01402399608437643

- Mowat, Charles Loch., Britain Between The Wars 1918-1940 (1955) pp 116–19, 138.

- Sales, Peter M. "WM Hughes and the Chanak Crisis of 1922." Australian Journal of Politics & History (1971) 17#3 pp: 392–405.

- Steiner, Zara. The Lights that Failed: European International History 1919–1933 (Oxford History of Modern Europe) (2005) pp 114–19

- Walder, David. The Chanak Affair (Macmillan, 1969)