Celtic language decline in England

Celtic language-death in England refers primarily to the process by which speakers of Brittonic languages in what is currently England switched to speaking English. This happened in most of England between about 400 and 1000 CE, though in Cornwall only in the eighteenth century.

Prior to about the fifth century CE, most people in Britain spoke Celtic languages (for the most part specifically Brittonic languages), although Vulgar Latin may have taken over in larger settlements, especially in the south-east. The fundamental reason for the death of these languages in early medieval England was the arrival in Britain of immigrants who spoke the Germanic language now known as Old English, particularly around the fifth century CE. Gradually, Celtic-speakers switched to speaking this English language until Celtic languages were no longer extensively spoken in what became England.

However, the precise processes by which this shift happened have been much debated, not least because the situation was strikingly different from, for example, post-Roman Gaul, Iberia, or North Africa, where Germanic-speaking invaders gradually switched to local languages.[1][2][3] Explaining the rise of Old English is therefore crucial in any account of cultural change in post-Roman Britain, and in particular to understanding the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, and is an important aspect of the history of English as well as the history of the Celtic languages.

The modern scholarly consensus is that the prime reason for the death of Brittonic in most of England was that in the fifth to sixth centuries, the new political elite of Old English-speaking immigrants made it politically expedient for other people in Britain to adopt their new rulers' language and Anglo-Saxon ethnicity.

Chronology

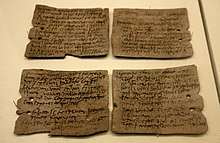

Fairly extensive information about language in Roman Britain is available from Roman administrative documents attesting to place- and personal-names, along with archaeological finds such as coins, the Bloomberg and Vindolanda tablets, and Bath curse tablets.[5] This shows that most inhabitants spoke British Celtic and/or British Latin until the Roman economy and administrative structures collapsed, around the early fifth century.

However, by the eighth century, when extensive evidence for the language situation in England is next available, it is clear that the dominant language was Old English, whose West Germanic ancestors were spoken in what is now the Netherlands, north-western Germany, and southern Denmark. There is no serious doubt that Old English was brought to Britain primarily during the fifth and sixth centuries by migrants from those regions.[6]

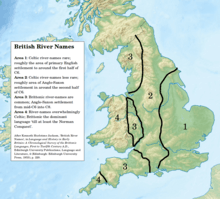

Because the main evidence for events in Britain during the crucial period 400–700 is archaeological, and seldom reveals linguistic information, while written evidence even after 700 remains patchy, the precise chronology of the spread of Old English is uncertain. However, Kenneth Jackson combined historical information from texts like Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People (731) with evidence for the linguistic origins of British river names to suggest the following chronology, which remains broadly accepted (see map at beginning of article):

- In Area I, Celtic names are rare and confined to large and medium-sized rivers. This area corresponds to English-language dominance up to c. 500–550.

- Area II shows English-language dominance c. 600.

- Area III, where even many small streams have Brittonic names, shows English-language dominance c. 700.

- In Area IV, Brittonic remained the dominant language until at least the Norman Conquest, and river names are overwhelmingly Celtic.[7]

Although Cumbric, in the north-west, seems to have died during the eleventh century,[8] Cornish continued to thrive until the early modern period, retreating at only around 10 km per century. But from about 1500, Cornish-English bilingualism became increasingly common, and Cornish retreated at more like 30 km per century. Cornish fell out of use entirely during the eighteenth century, though the last few decades have seen an attempted revival.[9]

During this period, England was also home to influential communities speaking Latin, Old Irish, Old Norse, and Anglo-Norman. None of these seems to have been a major long-term competitor to English and Brittonic, however.

Debate: was British Celtic being displaced by Latin before the arrival of English?

There is an ongoing discussion about the character of British Celtic and the extent of Latin-speaking in Roman Britain.[10][11][12] It is presently agreed that British Latin was spoken as a native language in Roman Britain, and that at least some of the dramatic changes that the Brittonic languages underwent around the sixth century were due to Latin-speakers switching language to Celtic,[13] possibly as Latin-speaking elites fled west from Anglo-Saxon settlers.[14] It seems likely that Latin was the language of most of the townspeople, of administration and the ruling class, the military and, following the introduction of Christianity, the church. However, British Celtic probably remained the language of the peasantry, which was the bulk of the population; the rural elite were probably bilingual.[15] However, at the most extreme, it has been suggested that Latin became the prevalent language of lowland Britain, in which case the story of Celtic language-death in what is now England begins with its extensive displacement by Latin.[16][17]

Thomas Toon has suggested that if the population of Roman Lowland Britain was bilingual in both Brittonic and Latin, such a multilingual society might adapt to the use of a third language, such as that spoken by the Germanic Anglo-Saxons, more readily than a monoglot population.[18]

Debate: why is there so little Brittonic influence on English?

Old English shows little obvious influence from Celtic or spoken Latin: there are vanishingly few English words of Brittonic origin.[21][22][23]

Into the later twentieth century, scholars' usual explanation for the lack of Celtic influence on English, supported by uncritical readings of the accounts of Gildas and Bede, was that Old English became dominant primarily because Germanic-speaking invaders killed, chased away, and/or enslaved the previous inhabitants of the areas that they settled. In recent decades, a few specialists have continued to support this interpretation.[24][25][26] Indeed, Peter Schrijver has said that 'to a large extent, it is linguistics that is responsible for thinking in terms of drastic scenarios' about demographic change in late Roman Britain.[27][28]

However, the development of contact linguistics in the later twentieth century, which involved study of present-day language contact in well understood social situations, gave scholars new ways to interpret the situation in early medieval Britain. Meanwhile, archaeological and genetic research suggest that a massive demographic change is unlikely to have taken place in fifth-century Britain. Indeed, even textual sources hint that people portrayed as ethnically Anglo-Saxon actually had British connections:[29] the West Saxon royal line was supposedly founded by a man named Cerdic, whose name derives from the Brittonic *Caraticos (cf. Welsh Ceredig),[30][31][32] whose supposed descendants Ceawlin[33] and Caedwalla (d. 689) also had Brittonic names.[34] The British name Caedbaed is found in the pedigree of the kings of Lindsey.[35] The name of King Penda and some other Mercian kings have more obvious Brittonic than Germanic etymologies, though they do not correspond to known Welsh personal names.[36][37] The early Northumbrian churchmen Chad of Mercia (a prominent bishop) and his brothers Cedd (also a bishop), Cynibil and Caelin, along with the supposedly first composer of Christian English verse, Cædmon, also have Brittonic names.[38][39]

The consensus among experts today is therefore that political dominance by a fairly small number of Old English-speakers could have driven large numbers of Britons to adopt Old English while leaving little detectable trace of this language-shift. If Old English became the most prestigious language in a particular region, speakers of other languages there would have sought to become bilingual and, over a few generations, stop speaking the less prestigious languages (in this case British Celtic and/or British Latin). The collapse of Britain's Roman economy seems to have left Britons living in a technologically similar society to their Anglo-Saxon neighbours, making it unlikely that Anglo-Saxons would need to borrow words for unfamiliar concepts.[40] Sub-Roman Britain saw a greater collapse in Roman institutions and infrastructure when compared to the situation in Roman Gaul and Hispania, perhaps especially after 407 A.D., when it is probable that most or all of the Roman field army stationed in Britain was withdrawn to support the continental ambitions of Constantine III. This would have led to a more dramatic reduction in the status and prestige of the Romanized culture in Britain, meaning that incoming Anglo-Saxons had little incentive to adopt British Celtic or Latin, while local people were more likely to abandon their languages in favour of the now higher status language of the Anglo-Saxons.[41][42] In these circumstances, it is plausible that Old English would borrow few words from the lower-status language(s).[43][44][45] Comparable language-shifts might be the eastward spread of Gaelic across what is now Scotland during the early Middle Ages;[46] the seventh- to ninth-century spread of Slavonic dialects in the Balkan region of the Eastern Roman Empire under the Bulgarian Empire;[47] or the later spread of Middle High German into previously Slavonic-speaking regions.[48]

This account, which demands only small numbers of politically dominant Germanic-speaking migrants to Britain, has become 'the standard explanation' for the gradual death of Celtic and spoken Latin in post-Roman Britain.[49][50][51][52][53] Within this consensus, debate continues, for example over whether at least some Germanic-speaking peasant-class immigrants must have been involved to bring about the language-shift;[54] what legal or social structures (such as enslavement or apartheid-like customs) might have promoted the high status of English;[55] and precisely how slowly Brittonic (and British Latin) disappeared in different regions.

An idiosyncratic alternative explanation for the spread of English that has gained extensive popular attention is Stephen Oppenheimer's suggestion that the lack of Celtic influence on English is because the ancestor of English was already widely spoken in Britain by the Belgae before the end of the Roman period.[56] However, Oppenheimer's ideas have not been found helpful in explaining the known facts: there is no evidence for a well established Germanic language in Britain before the fifth century, and Oppenheimer's idea contradicts the extensive evidence for the use of Celtic and Latin.[57][58]

Is it possible to detect substrate Celtic influence on English?

| Features | Coates[59] | Miller[60] | Hickey [61] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Two functionally distinct 'to be' verbs | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Northern subject rule | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Development of reflexives | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Rise of progressive | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Loss of external possessor | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Rise of the periphrastic "do" | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Negative comparative particle | ✔ | ||

| Rise of pronoun -en | ✔ | ||

| Merger of /kw-/, /hw-/ and /χw-/ | ✔ | ||

| Rise of "it" clefts | ✔ | ||

| Rise of sentential answers and tagging | ✔ | ||

| Preservation of θ and ð | ✔ | ||

| Loss of front rounded vowels | ✔ |

In the case of a fairly swift language-shift, involving second-language acquisition by adults, we should expect these learners' imperfect acquisition of Old English grammar and pronunciation to affect the language. As yet, there is no consensus that such effects are visible in the surviving evidence; thus a recent synthesis concludes that 'the evidence for Celtic influence on Old English is somewhat sparse, which only means that it remains elusive, not that it did not exist'.[62]

Reasons why Celtic influence on English may not be visible include the following.

- Our understanding of British Celtic and spoken Latin is limited.

- Old English texts were produced by a narrow and highly educated social elite whose written language might not represent everyday speech.

- Some aspects of language (e.g. intonation) are not represented in our written evidence.

- Native Celtic-speakers perhaps influenced English in ways that do not betray distinctively Celtic characteristics (e.g. general morphological simplification).

- In a few cases, late British Celtic (lBC) words were not substantially different from those of early Old English (eOE), allowing for easy assimilation:

| lBC | eOE | English |

|---|---|---|

| *landa | *landæ | "land" |

| *wira(s) | *weræ | "man" |

| *marha(s) | *marhæ | "horse" |

Still, although there is little consensus about the findings, extensive efforts have been made during the twenty-first century to identify substrate influence of Brittonic on English.[63][64][65][66]

Celtic influence on English has been suggested in several forms:

- Phonology. Between c. 450 and c. 700, Old English vowels underwent many changes, some of them unusual (such as the changes known as 'breaking'). It has been argued that some of these changes are a substrate effect caused by speakers of British Celtic adopting Old English during this period.[67]

- Morphology. Old English morphology underwent a steady simplification during the Old English period and beyond into the Middle English period. This would be characteristic of influence by an adult-learner population. Some simplifications that only become visible in Middle English may have entered low-status varieties of Old English earlier, but only appeared in higher-status written varieties at this late date.[68][69]

- Syntax. Over centuries, English has gradually acquired syntactic features in common with Celtic languages (such as the use of 'periphrastic "do" ').[70] Some scholars have argued that these reflect early Celtic influence, which however only became visible in the textual record late on. Substrate influence on syntax is considered especially likely during language shifts.[71]

Debate: why are there so few etymologically Celtic place-names in England?

Place-names are traditionally seen as important evidence for the history of language in post-Roman Britain for three main reasons:

- It is widely assumed that, even when first attested later, names were often coined in the Settlement Period.

- Although it is not clear who in society determined what places were called, place-names may reflect the usage of a broader section of the population than written texts.

- Place-names provide evidence for language in regions for which we lack written sources.[73]

Post-Roman place-names in England begin to be attested from around 670, pre-eminently in Anglo-Saxon charters;[74] they have been intensively surveyed by the English and Scottish Place-Name Societies.

Except in Cornwall, the vast majority of place-names in England are easily etymologised as Old English (or Old Norse, due to later Viking influence), demonstrating the dominance of English across post-Roman England. This has traditionally been seen as evidence for a cataclysmic cultural and demographic shift at the end of the Roman period, in which not only the Brittonic and Latin languages, but also Brittonic and Latin place-names, and even Brittonic- and Latin-speakers, were swept away.[75][76][77][78]

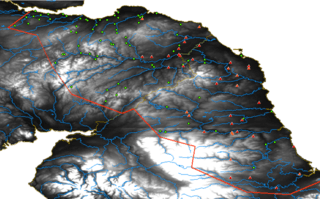

In recent decades, research on Celtic toponymy, driven by the development of Celtic studies and particularly by Andrew Breeze and Richard Coates, has complicated this picture: more names in England and southern Scotland have Brittonic, or occasionally Latin, etymologies than was once thought.[79] Earlier scholars often did not notice this because they were unfamiliar with Celtic languages. For example, Leatherhead was once etymologised as Old English lēod-rida, meaning "place where people [can] ride [across the river]".[80] But lēod has never been discovered in place-names before or since, and *ride 'place suitable for riding' was merely speculation. Coates showed that Brittonic lēd-rïd 'grey ford' was more plausible.[81] In particular, there are clusters of Cumbric place-names in northern Cumbria[82] and to the north of the Lammermuir Hills.[83] Even so, it is clear that Brittonic and Latin place-names in the eastern half of England are extremely rare, and although they are noticeably more common in the western half, they are still a tiny minority─2% in Cheshire, for example.[84]

Likewise, some entirely Old English names explicitly point to Roman structures, usually using Latin loan-words, or to the presence of Brittonic-speakers. Names like Wickham clearly denoted the kind of Roman settlement known in Latin as a vicus, and others end in elements denoting Roman features, such as -caster, denoting castra ('forts').[85] There is a substantial body of names along the lines of Walton/Walcot/Walsall/Walsden, many of which must include the Old English word wealh in the sense 'Celtic-speaker',[86][87] and Comberton, many of which must include Old English Cumbre 'Britons'.[88] These are likely to have been names for enclaves of Brittonic-speakers─but again are not that numerous.

In the last decade, however, scholars have stressed that Welsh and Cornish place-names from the Roman period seem no more likely to survive than Roman names in England: 'clearly name loss was a Romano-British phenomenon, not just one associated with Anglo-Saxon incomers'.[89][90] Therefore, other explanations for the replacement of Roman period place-names which allow for a less cataclysmic shift to English naming include:

- Adaptation rather than replacement. Names that came to look like they were coined as Old English may actually come from Roman-period ones. For example, the Old English name for the city of York, Eoforwīc (earlier *Eburwīc), transparently means 'boar-village'. We only know that the first part of the name was borrowed from the earlier Romanised Celtic name Eburacum because that earlier name is one of relatively few Roman British place-names that were recorded: otherwise we would assume the Old English name was coined from scratch. (Likewise, the Old English name was in turn adapted into Norse as Jórvík, which transparently means 'horse-bay', and again it would not be obvious that this was based on an earlier Old English name were that not recorded.)[91][92][93][94][95]

- Invisible multilingualism. Place-names which only survive in Old English form could have had Brittonic counterparts for long periods without those being recorded. For example, the Welsh name of York, Efrog, derives independently from the Roman Eboracum; other Brittonic names for English places might also have continued in parallel to the English ones.[96][97]

- Later evidence for place-names may not be as indicative of naming in the immediate post-Roman period as was once assumed. In names attested up to 731, 26% are etymologically partly non-English,[98] and 31% have since fallen from use.[99] Settlements and land tenure may have been relatively unstable in the post-Roman period, leading to a high natural rate of place-name replacement, enabling names coined in the increasingly dominant English language to replace names inherited from the Roman period relatively swiftly.[100][101]

Thus place-names are important for showing the swift spread of English across England, and also provide important glimpses into details of the history of Brittonic and Latin in the region.[102][103] But they do not demand a single or simple model for explaining the spread of English.

See also

References

- ↑ Bryan Ward-Perkins, ‘Why did the Anglo-Saxons not become more British?’, English Historical Review, 115 (2000), 513–33.

- ↑ Chris Wickham, Framing the Early Middle Ages: Europe and the Mediterranean 400-800 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 311-12.

- ↑ Hills, C. M. (2013). "Anglo-Saxon Migrations". The Encyclopedia of Global Human Migration. Wiley-Blackwell. doi:10.1002/9781444351071.wbeghm029.

- ↑ After Kenneth Hurlstone Jackson, 'British River Names', in Language and History in Early Britain: A Chronological Survey of the Brittonic Languages, First to Twelfth Century A.D., Edinburgh University Publications, Language and Literature, 4 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1953), p. 220.

- ↑ E.g. A. L. F. Rivet and Colin Smith, The Place-Names of Roman Britain (London: Batsford, 1979).

- ↑ Cf. Hans Frede Nielsen, The Continental Backgrounds of English and its Insular Development until 1154 (Odense, 1998), pp. 77–79; Peter Trudgill, New-Dialect Formation: The Inevitability of Colonial Englishes (Edinburgh, 2004), p. 11.

- ↑ Kenneth Hurlstone Jackson, Language and History in Early Britain: A Chronological Survey of the Brittonic Languages, First to Twelfth Century A.D., Edinburgh University Publications, Language and Literature, 4 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1953), p. 220.

- ↑ Diana Whaley, A Dictionary of Lake District Place-names, Regional series (English Place-Name Society), 1 (Nottingham: English Place-Name Society, 2006), esp. pp. xix-xxi.

- ↑ Ken George, 'Cornish', in The Celtic Languages, ed. by Martin J. Ball and James Fife (London: Routledge, 1993), pp. 410–68 (pp. 411–15).

- ↑ David N. Parsons, 'Sabrina in the thorns: place-names as evidence for British and Latin in Roman Britain', Transactions of the Royal Philological Society, 109.2 (July 2011), 113–37.

- ↑ Paul Russell, 'Latin and British in Roman and Post-Roman Britain: methodology and morphology', Transactions of the Royal Philological Society, 109.2 (July 2011), 138–57.

- ↑ Peter Schrijver, Language Contact and the Origins of the Germanic Languages, Routledge Studies in Linguistics, 13 (New York: Routledge, 2014), pp. 31–91.

- ↑ D. Gary Miller, External Influences on English: From Its Beginnings to the Renaissance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 25–28.

- ↑ Peter Schrijver, Language Contact and the Origins of the Germanic Languages, Routledge Studies in Linguistics, 13 (New York: Routledge, 2014), pp. 31–48.

- ↑ Sawyer, P.H. (1998). From Roman Britain to Norman England. p. 74. ISBN 0415178940.

- ↑ Peter Schrijver, ‘The Rise and Fall of British Latin: Evidence from English and Brittonic’, in The Celtic Roots of English, ed. by Markku Filppula, Juhani Klemola and Heli Pitkänen, Studies in Languages, 37 (Joensuu: University of Joensuu, Faculty of Humanities, 2002), pp. 87–110.

- ↑ Peter Schrijver, ‘What Britons spoke around 400 AD’, in N. J. Higham (ed.), Britons in Anglo-Saxon England (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2007), pp. 165–71.

- ↑ Toon, T.E. The Politics of Early Old English Sound Change, 1983.

- ↑ Fred Orton and Ian Wood with Clare Lees, Fragments of History: Rethinking the Ruthwell and Bewcastle Monuments (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007), pp. 121–139.

- ↑ Alaric Hall, ‘Interlinguistic Communication in Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum’, in Interfaces between Language and Culture in Medieval England: A Festschrift for Matti Kilpiö, ed. by Alaric Hall, Olga Timofeeva, Ágnes Kiricsi and Bethany Fox, The Northern World, 48 (Leiden: Brill, 2010), pp. 37-80 (pp. 73–74).

- ↑ Kastovsky, Dieter, ‘Semantics and Vocabulary’, in The Cambridge History of the English Language, Volume 1: The Beginnings to 1066, ed. by Richard M. Hogg (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), pp. 290–408 (pp. 301–20).

- ↑ Matthew Townend, 'Contacts and Conflicts: Latin, Norse, and French', in The Oxford History of English, ed. by Lynda Mugglestone, rev. edn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 75–105 (pp. 78–80).

- ↑ A. Wollmann, 'Lateinisch-Altenglische Lehnbeziehungen im 5. und 6. Jahrhundert', in Britain 400–600, ed. by A. Bammesberger and A. Wollmann, Anglistische Forschungen, 205 (Heidelberg: Winter, 1990), pp. 373–96.

- ↑ D. Hooke, 'The Anglo-Saxons in England in the seventh and eighth centuries: aspects of location in space', in The Anglo-Saxons from the Migration Period to the Eighth Century: an Ethnographic Perspective, ed. by J. Hines (Woodbridge: Boydell, 1997), 64–99 (p. 68).

- ↑ O. J. Padel. 2007. “Place-names and the Saxon conquest of Devon and Cornwall.” In Britons in Anglo-Saxon England [Publications of the Manchester Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies 7], N. Higham (ed.), 215–230. Woodbridge: Boydell.

- ↑ R. Coates. 2007. “Invisible Britons: The view from linguistics.” In Britons in Anglo-Saxon England [Publications of the Manchester Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies 7], N. Higham (ed.), 172–191. Woodbridge: Boydell.

- ↑ Peter Schrijver, Language Contact and the Origins of the Germanic Languages, Routledge Studies in Linguistics, 13 (New York: Routledge, 2014), quoting p. 16.

- ↑ Matthew Townend, 'Contacts and Conflicts: Latin, Norse, and French', in The Oxford History of English, ed. by Lynda Mugglestone, rev. edn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 75–105 (pp. 78–80).

- ↑ Catherine Hills (2003) Origins of the English, Duckworth, pp. 55, 105

- ↑ Parsons, D. (1997) British *Caraticos, Old English Cerdic, Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies, 33, pp, 1–8.

- ↑ Koch, J.T., (2006) Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1-85109-440-7, pp. 392–393.

- ↑ Myres, J.N.L. (1989) The English Settlements. Oxford University Press, p. 146.

- ↑ Bryan Ward-Perkins, ‘Why did the Anglo-Saxons not become more British?’, English Historical Review, 115 (2000), 513–33 (p. 513).

- ↑ Yorke, B. (1990), Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England, London: Seaby, ISBN 1-85264-027-8 pp. 138–139

- ↑ Basset, S. (ed.) (1989) The Origins of Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms, Leicester University Press

- ↑ Koch, J.T., (2006) Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1-85109-440-7, p. 60

- ↑ Higham and Ryan (2013), pp. 143, 178

- ↑ Koch, J.T., (2006) Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1-85109-440-7, p. 360

- ↑ Higham and Ryan (2013), p. 143.

- ↑ Chris Wickham, The Inheritance of Rome: A History of Europe from 400 to 1000 (London: Allen Lane, 2009), p. 157.

- ↑ Higham, Nicholas (2013). The Anglo-Saxon World. pp. 109–111. ISBN 0300125348.

- ↑ Bryan Ward-Perkins, ‘Why did the Anglo-Saxons not become more British?’, English Historical Review, 115 (2000), 513–33 (p. 529).

- ↑ Matthew Townend, 'Contacts and Conflicts: Latin, Norse, and French', in The Oxford History of English, ed. by Lynda Mugglestone, rev. edn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 75–105 (pp. 78–80).

- ↑ D. Gary Miller, External Influences on English: From Its Beginnings to the Renaissance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 35–40).

- ↑ Kastovsky, Dieter, ‘Semantics and Vocabulary’, in The Cambridge History of the English Language, Volume 1: The Beginnings to 1066, ed. by Richard M. Hogg (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), pp. 290–408 (pp. 317–18).

- ↑ Alaric Hall, 'The Instability of Place-names in Anglo-Saxon England and Early Medieval Wales, and the Loss of Roman Toponymy', in Sense of Place in Anglo-Saxon England, ed. by Richard Jones and Sarah Semple (Donington: Tyas, 2012), pp. 101–29 (p. 103).

- ↑ Chris Wickham, The Inheritance of Rome: A History of Europe from 400 to 1000 (London: Allen Lane, 2009), pp. 272-73.

- ↑ Heinrich Härke, 'Anglo-Saxon Immigration and Ethnogenesis', Medieval Archaeology, 55 (2011), 1–28.

- ↑ Quoting Matthew Townend, 'Contacts and Conflicts: Latin, Norse, and French', in The Oxford History of English, ed. by Lynda Mugglestone, rev. edn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 75–105 (p. 80).

- ↑ Alaric Hall, 'The Instability of Place-names in Anglo-Saxon England and Early Medieval Wales, and the Loss of Roman Toponymy', in Sense of Place in Anglo-Saxon England, ed. by Richard Jones and Sarah Semple (Donington: Tyas, 2012), pp. 101–29 (pp. 102–3).

- ↑ Pryor 2005 Pryor, Francis. Britain AD: A Quest for Arthur, England and the Anglo-Saxons. HarperCollins UK, 2009.

- ↑ D. Gary Miller, External Influences on English: From Its Beginnings to the Renaissance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 35–40.

- ↑ Nicholas J. Higham and Martin J. Ryan, The Anglo-Saxon World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), pp. 97–99.

- ↑ Chris Wickham, Framing the Early Middle Ages: Europe and the Mediterranean 400-800 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 311-12.

- ↑ Heinrich Härke, 'Anglo-Saxon Immigration and Ethnogenesis', Medieval Archaeology, 55 (2011), 1–28.

- ↑ Oppenheimer, Stephen (2006). The Origins of the British: A Genetic Detective Story: Constable and Robinson, London. ISBN 978-1-84529-158-7.

- ↑ Alaric Hall, 'A gente Anglorum appellatur: The Evidence of Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum for the Replacement of Roman Names by English Ones During the Early Anglo-Saxon Period', in Words in Dictionaries and History: Essays in Honour of R. W. McConchie, ed. by Olga Timofeeva and Tanja Säily, Terminology and Lexicography Research and Practice, 14 (Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2011), pp. 219–31 (pp. 220–21).

- ↑ Hills C.M. (2013). Anglo-Saxon Migrations. The Encyclopedia of Global Human Migration. Wiley-Blackwell. DOI: 10.1002/9781444351071.wbeghm029.

- ↑ Coates, Richard, 2010. Review of Filppula et al. 2008. Language 86: 441–444.

- ↑ Miller, D. Gary. External Influences on English: From its Beginnings to the Renaissance. Oxford 2012: Oxford University Press

- ↑ Hickey, Raymond. Early English and the Celtic hypothesis. in Terttu Nevalainen & Elizabeth Closs Traugott (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the History of English. Oxford 2012: Oxford University Press: 497–507.

- ↑ Quoting D. Gary Miller, External Influences on English: From Its Beginnings to the Renaissance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 35–40 (p. 39).

- ↑ Filppula, Markku, and Juhani Klemola, eds. 2009. Re-evaluating the Celtic Hypothesis. Special issue of English Language and Linguistics 13.2.

- ↑ The Celtic Roots of English, ed. by Markku Filppula, Juhani Klemola and Heli Pitkänen, Studies in Languages, 37 (Joensuu: University of Joensuu, Faculty of Humanities, 2002).

- ↑ Hildegard L. C. Von Tristram (ed.), The Celtic Englishes, Anglistische Forschungen 247, 286, 324, 3 vols (Heidelberg: Winter, 1997–2003).

- ↑ Peter Schrijver, Language Contact and the Origins of the Germanic Languages, Routledge Studies in Linguistics, 13 (New York: Routledge, 2014), pp. 12–93.

- ↑ Schrijver, P. (2013) 'Language Contact and the Origins of the Germanic Languages', Routledge ISBN 1134254490, pp. 60-71

- ↑ Alaric Hall, 'A gente Anglorum appellatur: The Evidence of Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum for the Replacement of Roman Names by English Ones During the Early Anglo-Saxon Period', in Words in Dictionaries and History: Essays in Honour of R. W. McConchie, ed. by Olga Timofeeva and Tanja Säily, Terminology and Lexicography Research and Practice, 14 (Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2011), pp. 219–31.

- ↑ Peter Schrijver, Language Contact and the Origins of the Germanic Languages, Routledge Studies in Linguistics, 13 (New York: Routledge, 2014), pp. 20–22.

- ↑ Poussa, Patricia. 1990. 'A Contact-Universals Origin for Periphrastic Do, with Special Consideration of OE-Celtic Contact'. In Papers from the Fifth International Conference on English Historical Linguistics, ed. Sylvia Adamson, Vivien Law, Nigel Vincent, and Susan Wright, 407–34. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

- ↑ Hickey, Raymond. 1995. 'Early Contact and Parallels between English and Celtic'. Vienna English Working Papers 4: 87–119.

- ↑ Map by Alaric Hall, first published here as part of Bethany Fox, 'The P-Celtic Place-Names of North-East England and South-East Scotland', The Heroic Age, 10 (2007).

- ↑ Alaric Hall, 'The Instability of Place-names in Anglo-Saxon England and Early Medieval Wales, and the Loss of Roman Toponymy', in Sense of Place in Anglo-Saxon England, ed. by Richard Jones and Sarah Semple (Donington: Tyas, 2012), pp. 101–29 (pp. 101–4).

- ↑ Nicholas J. Higham and Martin J. Ryan, The Anglo-Saxon World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), p. 99.

- ↑ D. Hooke, 'The Anglo-Saxons in England in the seventh and eighth centuries: aspects of location in space', in The Anglo-Saxons from the Migration Period to the Eighth Century: an Ethnographic Perspective, ed. by J. Hines (Woodbridge: Boydell, 1997), 64–99 (p. 68).

- ↑ O. J. Padel. 2007. “Place-names and the Saxon conquest of Devon and Cornwall.” In Britons in Anglo-Saxon England [Publications of the Manchester Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies 7], N. Higham (ed.), 215–230. Woodbridge: Boydell.

- ↑ R. Coates. 2007. “Invisible Britons: The view from linguistics.” In Britons in Anglo-Saxon England [Publications of the Manchester Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies 7], N. Higham (ed.), 172–191. Woodbridge: Boydell.

- ↑ Alaric Hall, 'The Instability of Place-names in Anglo-Saxon England and Early Medieval Wales, and the Loss of Roman Toponymy', in Sense of Place in Anglo-Saxon England, ed. by Richard Jones and Sarah Semple (Donington: Tyas, 2012), pp. 101–29 (pp. 102–3).

- ↑ E.g. Richard Coates and Andrew Breeze, Celtic Voices, English Places: Studies of the Celtic impact on place-names in Britain (Stamford: Tyas, 2000).

- ↑ Gover, J.E.B., A. Mawer and F.M. Stenton, with A. Bonner. 1934. The place-names of Surrey. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (SEPN vol. 11).

- ↑ Richard Coates, 'Methodological Reflexions on Leatherhead', Journal of the English Place-Name Society, 12 (1979–80), 70–74.

- ↑ Diana Whaley, A Dictionary of Lake District Place-names, Regional series (English Place-Name Society), 1 (Nottingham: English Place-Name Society, 2006), esp. pp. xix-xxi.

- ↑ Bethany Fox, 'The P-Celtic Place-Names of North-East England and South-East Scotland', The Heroic Age, 10 (2007).

- ↑ Nicholas J. Higham and Martin J. Ryan, The Anglo-Saxon World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), pp. 98–101.

- ↑ David N. Parsons, 'Sabrina in the thorns: place-names as evidence for British and Latin in Roman Britain', Transactions of the Royal Philological Society, 109.2 (July 2011), 113–37 (pp. 125–28).

- ↑ Miller, Katherine, 'The Semantic Field of Slavery in Old English: Wealh, Esne, Þræl' (unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Leeds, 2014), esp. p. 90.

- ↑ Hamerow, H. 1993 Excavations at Mucking, Volume 2: The Anglo-Saxon Settlement (English Heritage Archaeological Report 21)

- ↑ Patrick Sims-Williams, Religion and Literature in Western England 600-800, Cambridge Studies in Anglo-Saxon England, 3 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), p. 24.

- ↑ Quoting Nicholas J. Higham and Martin J. Ryan, The Anglo-Saxon World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), p. 99.

- ↑ Alaric Hall, 'The Instability of Place-names in Anglo-Saxon England and Early Medieval Wales, and the Loss of Roman Toponymy', in Sense of Place in Anglo-Saxon England, ed. by Richard Jones and Sarah Semple (Donington: Tyas, 2012), pp. 101–29 (pp. 112–13).

- ↑ Higham and Ryan (2013), p. 100.

- ↑ Smith, C. 1980. “The survival of Romano-British toponymy.” Nomina 4: 27–40.

- ↑ Carole Hough. 2004. The (non?)-survival of Romano-British toponymy. Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 105:25–32.

- ↑ Bethany Fox, 'The P-Celtic Place-Names of North-East England and South-East Scotland', The Heroic Age, 10 (2007), §23.

- ↑ Alaric Hall, ‘A gente Anglorum appellatur: The Evidence of Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum for the Replacement of Roman Names by English Ones During the Early Anglo-Saxon Period', in Words in Dictionaries and History: Essays in Honour of R. W. McConchie, ed. by Olga Timofeeva and Tanja Säily, Terminology and Lexicography Research and Practice, 14 (Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2011), pp. 219–31.

- ↑ Nicholas J. Higham and Martin J. Ryan, The Anglo-Saxon World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), p. 100.

- ↑ Alaric Hall, ‘A gente Anglorum appellatur: The Evidence of Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum for the Replacement of Roman Names by English Ones During the Early Anglo-Saxon Period', in Words in Dictionaries and History: Essays in Honour of R. W. McConchie, ed. by Olga Timofeeva and Tanja Säily, Terminology and Lexicography Research and Practice, 14 (Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2011), pp. 219–31 (p. 221).

- ↑ Barrie Cox, ‘The Place-Names of the Earliest English Records’, Journal of the English Place-Name Society, 8 (1975–76), 12–66.

- ↑ Alaric Hall, 'The Instability of Place-names in Anglo-Saxon England and Early Medieval Wales, and the Loss of Roman Toponymy', in Sense of Place in Anglo-Saxon England, ed. by Richard Jones and Sarah Semple (Donington: Tyas, 2012), pp. 101–29 (pp. 108–9).

- ↑ Alaric Hall, 'The Instability of Place-names in Anglo-Saxon England and Early Medieval Wales, and the Loss of Roman Toponymy', in Sense of Place in Anglo-Saxon England, ed. by Richard Jones and Sarah Semple (Donington: Tyas, 2012), pp. 101–29.

- ↑ Nicholas J. Higham and Martin J. Ryan, The Anglo-Saxon World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Kenneth Hurlstone Jackson, Language and History in Early Britain: A Chronological Survey of the Brittonic Languages, First to Twelfth Century A.D., Edinburgh University Publications, Language and Literature, 4 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1953).

- ↑ David N. Parsons, 'Sabrina in the thorns: place-names as evidence for British and Latin in Roman Britain', Transactions of the Royal Philological Society, 109.2 (July 2011), 113–37.