Calcium sulfate

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.029.000 |

| E number | E516 (acidity regulators, ...) |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number | WS6920000 |

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| CaSO4 | |

| Molar mass | 136.14 g/mol (anhydrous) 145.15 g/mol (hemihydrate) 172.172 g/mol (dihydrate) |

| Appearance | white solid |

| Odor | odorless |

| Density | 2.96 g/cm3 (anhydrous) 2.32 g/cm3 (dihydrate) |

| Melting point | 1,460 °C (2,660 °F; 1,730 K) (anhydrous) |

| 0.21g/100ml at 20 °C (anhydrous)[1] 0.24 g/100ml at 20 °C (dihydrate)[2] | |

Solubility product (Ksp) |

4.93 × 10−5 mol2L−2 (anhydrous) 3.14 × 10−5 (dihydrate) [3] |

| Solubility in glycerol | slightly soluble (dihydrate) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 10.4 (anhydrous) 7.3 (dihydrate) |

| -49.7·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Structure | |

| orthorhombic | |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std molar entropy (S |

107 J·mol−1·K−1 [4] |

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH |

-1433 kJ/mol[4] |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | See: data page ICSC 1589 |

| NFPA 704 | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| US health exposure limits (NIOSH): | |

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 15 mg/m3 (total) TWA 5 mg/m3 (resp) [for anhydrous form only][5] |

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 10 mg/m3 (total) TWA 5 mg/m3 (resp) [anhydrous only][5] |

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

N.D.[5] |

| Related compounds | |

Other cations |

Magnesium sulfate Strontium sulfate Barium sulfate |

Related desiccants |

Calcium chloride Magnesium sulfate |

Related compounds |

Plaster of Paris Gypsum |

| Supplementary data page | |

| Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. | |

Thermodynamic data |

Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas |

| UV, IR, NMR, MS | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Calcium sulfate (or calcium sulphate) is the inorganic compound with the formula CaSO4 and related hydrates. In the form of γ-anhydrite (the anhydrous form), it is used as a desiccant. One particular hydrate is better known as plaster of Paris, and another occurs naturally as the mineral gypsum. It has many uses in industry. All forms are white solids that are poorly soluble in water.[6] Calcium sulfate causes permanent hardness in water.

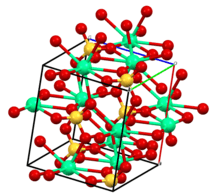

Hydration states and crystallographic structures

The compound exists in three levels of hydration corresponding to different crystallographic structures and to different minerals in the nature:

Uses

The main use of calcium sulfate is to produce plaster of Paris and stucco. These applications exploit the fact that calcium sulfate which has been powdered and calcined forms a moldable paste upon hydration and hardens as crystalline calcium sulfate dihydrate. It is also convenient that calcium sulfate is poorly soluble in water and does not readily dissolve in contact with water after its solidification.

Hydration and dehydration reactions

With judicious heating, gypsum converts to the partially dehydrated mineral called calcium sulfate hemihydrate, calcined gypsum, and plaster of Paris.This material has the formula CaSO4·(nH2O), where 0.5 ≤ n ≤ 0.8.[9] Temperatures between 100 °C and 150 °C (302 °F) are required to drive off the water within its structure. The details of the temperature and time depend on ambient humidity. Temperatures as high as 170 °C are used in industrial calcination, but at these temperatures γ-anhydrite begins to form. The heat energy delivered to the gypsum at this time (the heat of hydration) tends to go into driving off water (as water vapor) rather than increasing the temperature of the mineral, which rises slowly until the water is gone, then increases more rapidly. The equation for the partial dehydration is:

- CaSO4 · 2 H2O → CaSO4 · 0.5 H2O + 1.5 H2O ↑

The endothermic property of this reaction is relevant to the performance of drywall, conferring fire resistance to residential and other structures. In a fire, the structure behind a sheet of drywall will remain relatively cool as water is lost from the gypsum, thus preventing (or substantially retarding) damage to the framing (through combustion of wood members or loss of strength of steel at high temperatures) and consequent structural collapse. But at higher temperatures, calcium sulfate will release oxygen and act as an oxidizing agent. This property is used in aluminothermy. In contrast to most minerals, which when rehydrated simply form liquid or semi-liquid pastes, or remain powdery, calcined gypsum has an unusual property: when mixed with water at normal (ambient) temperatures, it quickly reverts chemically to the preferred dihydrate form, while physically "setting" to form a rigid and relatively strong gypsum crystal lattice:

- CaSO4 · 0.5 H2O + 1.5 H2O → CaSO4 · 2 H2O

This reaction is exothermic and is responsible for the ease with which gypsum can be cast into various shapes including sheets (for drywall), sticks (for blackboard chalk), and molds (to immobilize broken bones, or for metal casting). Mixed with polymers, it has been used as a bone repair cement. Small amounts of calcined gypsum are added to earth to create strong structures directly from cast earth, an alternative to adobe (which loses its strength when wet). The conditions of dehydration can be changed to adjust the porosity of the hemihydrate, resulting in the so-called alpha and beta hemihydrates (which are more or less chemically identical).

On heating to 180 °C, the nearly water-free form, called γ-anhydrite (CaSO4·nH2O where n = 0 to 0.05) is produced. γ-Anhydrite reacts slowly with water to return to the dihydrate state, a property exploited in some commercial desiccants. On heating above 250 °C, the completely anhydrous form called β-anhydrite or "natural" anhydrite is formed. Natural anhydrite does not react with water, even over geological timescales, unless very finely ground.

The variable composition of the hemihydrate and γ-anhydrite, and their easy inter-conversion, is due to their nearly identical crystal structures containing "channels" that can accommodate variable amounts of water, or other small molecules such as methanol.

Other uses

The calcium sulfate hydrates are used as a coagulant in products such as tofu.[10]

Up to the 1970s, commercial quantities of sulfuric acid were produced in Whitehaven (Cumbria, UK) from anhydrous calcium sulfate. Upon being mixed with shale or marl, and roasted, the sulfate liberates sulfur trioxide gas, a precursor in sulfuric acid production, the reaction also produces calcium silicate, a mineral phase essential in cement clinker production.[11]

- CaSO4 + SiO2 → CaSiO3 + SO3

When sold at the anhydrous state as a desiccant with a color-indicating agent under the name Drierite, it appears blue (anhydrous) or pink (hydrated) due to impregnation with cobalt(II) chloride, which functions as a moisture indicator.

Production and occurrence

The main sources of calcium sulfate are naturally occurring gypsum and anhydrite, which occur at many locations worldwide as evaporites. These may be extracted by open-cast quarrying or by deep mining. World production of natural gypsum is around 127 million tonnes per annum.[12]

In addition to natural sources, calcium sulfate is produced as a by-product in a number of processes:

- In flue-gas desulfurization, exhaust gases from fossil-fuel power stations and other processes (e.g. cement manufacture) are scrubbed to reduce their sulfur oxide content, by injecting finely ground limestone or lime. This produces an impure calcium sulfite, which oxidizes on storage to calcium sulfate.

- In the production of phosphoric acid from phosphate rock, calcium phosphate is treated with sulfuric acid and calcium sulfate precipitates.

- In the production of hydrogen fluoride, calcium fluoride is treated with sulfuric acid, precipitating calcium sulfate.

- In the refining of zinc, solutions of zinc sulfate are treated with lime to co-precipitate heavy metals such as barium.

- Calcium sulfate can also be recovered and re-used from scrap drywall at construction sites.

These precipitation processes tend to concentrate radioactive elements in the calcium sulfate product. This issue is particular with the phosphate by-product, since phosphate ores naturally contain uranium and its decay products such as radium-226, lead-210 and polonium-210.

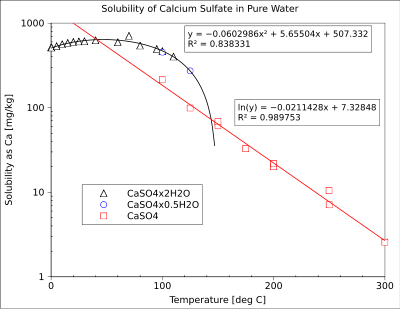

Calcium sulfate is also a common component of fouling deposits in industrial heat exchangers, because its solubility decreases with increasing temperature (see the specific section on the retrograde solubility).

Mars

2011 findings by the Opportunity rover on Mars show a form of calcium sulfate in a vein on the surface. Images suggest the mineral is gypsum.[13]

Retrograde solubility

The dissolution of the different crystalline phases of calcium sulfate in water is exothermic and release heat (decrease in Gibbs free energy: Δ G < 0). As an immediate consequence, to proceed, the dissolution reaction needs to evacuate this heat that can be considered as a product of reaction. If the system is cooled, the dissolution equilibrium will evolve towards the right according to the Le Chatelier principle and calcium sulfate will dissolve more easily. The solubility of calcium sulfate increases thus when the temperature decreases. If the temperature of the system is raised, the reaction heat cannot dissipate and the equilibrium will regress towards the left according to Le Chatelier principle. The solubility of calcium sulfate decreases thus when temperature increases. This contra-intuitive solubility behaviour is called retrograde solubility. It is less common than for most of the salts whose dissolution reaction is endothermic (i.e., the reaction consumes heat: increase in Gibbs free energy: Δ G > 0) and whose solubility increases with temperature. Another calcium compound, calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2, portlandite) also exhibits a retrograde solubility for the same thermodynamic reason: because its dissolution reaction is also exothermic and releases heat. So, to dissolve higher amounts of calcium sulfate or calcium hydroxide in water, it is necessary to cool down the solution close to its freezing point in place to increase its temperature or to use nearly boiling water.

The retrograde solubility of calcium sulfate is also responsible for its precipitation in the hottest zone of heating systems and for its contribution to the formation of scale in boilers along with the precipitation of calcium carbonate whose solubility also decreases when CO2 degasses from hot water or can escape out of the system.

See also

References

- ↑ S. Gangolli (1999). The Dictionary of Substances and Their Effects: C. Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 71. ISBN 0-85404-813-8.

- ↑ American Chemical Society (2006). Reagent chemicals: specifications and procedures : American Chemical Society specifications, official from January 1, 2006. Oxford University Press. p. 242. ISBN 0-8412-3945-2.

- ↑ D.R. Linde (ed.) "CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics", 83rd Edition, CRC Press, 2002

- 1 2 Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles 6th Ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. A21. ISBN 0-618-94690-X.

- 1 2 3 "NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards #0095". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ↑ Franz Wirsching "Calcium Sulfate" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2012 Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a04_555

- ↑ Morikawa, H.; Minato, I.; Tomita, T.; Iwai, S. (1975). "Anhydrite: A refinement". Acta Crystallographica Section B. 31 (8): 2164. doi:10.1107/S0567740875007145.

- ↑ Cole, W.F.; Lancucki, C.J. (1974). "A refinement of the crystal structure of gypsum CaSO4·2H2O". Acta Crystallographica Section B. 30 (4): 921. doi:10.1107/S0567740874004055.

- 1 2 Taylor H.F.W. (1990) Cement Chemistry. Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-683900-X, pp. 186-187.

- ↑ About tofu coagulant. Retrieved 9 Jan. 2008.

- ↑ Whitehaven Coast Archeological Survey

- ↑ Gypsum, USGS, 2008

- ↑ "NASA Mars Opportunity rover finds mineral vein deposited by water". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. December 7, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2013.