Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

| Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Cervical dysplasia, cervical interstitial neoplasia |

| |

| Positive visual inspection with acetic acid of the cervix for CIN-1 | |

| Specialty | Gynecology |

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), also known as cervical dysplasia, is the abnormal growth of cells on the surface of the cervix that could potentially lead to cervical cancer. [1] More specifically, CIN refers to the potentially premalignant transformation of cells of the cervix.

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia most commonly occurs at the squamo-columnar junction (SCJ) of the cervix, referring to a transitional area between squamous epithelium of the vagina and the columnar epithelium of the endocervix but can also occur in vaginal walls and vulvar epithelium. CIN is graded on a 1-3 scale, 1 being less abnormal than 3 (see classification section below).

Human papilloma virus (HPV) infection is necessary for the development of CIN but not all with this infection develop cervical neoplasia. [2] A large number of women with HPV infection will not develop CIN or cervical cancer, but those with an HPV infection that does not go away on its own and lasts more than 1 or 2 years have a higher risk of development of a higher grade of CIN. [3]

Like other intraepithelial neoplasias, CIN is not cancer, and it is usually curable.[4] Most cases of CIN remain stable, or are eliminated by the person's immune system without need for intervention. However a small percentage of cases progress to become cervical cancer, usually cervical squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), if left untreated.[5]

Signs and symptoms

There are no specific symptoms of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia alone. However, signs and symptoms of cervical cancer include: abnormal or post-menopausal bleeding, abnormal discharge, changes in bladder or bowel function, and pelvic pain on examination, abnormal visualization or palpation of cervix.[6] HPV infection of the lower genital tract can manifest with genital warts or non-genital lesions or can be asymptomatic.

| Symptoms of cervical cancer |

| Abnormal or post-menopausal bleeding

Abnormal discharge Changes in bladder or bowel function Pelvic pain on examination |

Causes

The cause of CIN is chronic infection of the cervix with the sexually transmitted human papillomavirus (HPV), especially the high-risk HPV types 16 or 18. Some groups of women have been found to be at a higher risk of developing CIN:[1]

- Women who become infected by a "high risk" type of HPV, such as 16, 18, 31, or 33

- Women who are immunodeficient

- Women who give birth before age 17

A number of risk factors have been shown to increase a woman's likelihood of developing CIN,[7] including poor diet, multiple sexual partners, lack of condom use, and cigarette smoking.

A compromised immune system, cigarette smoking, and infection with HIV increase the likelihood of persistence of HPV infection. [8]

Pathophysiology

The earliest microscopic change corresponding to CIN is dysplasia of the epithelial or surface lining of the cervix, which is essentially undetectable by the woman. Cellular changes associated with HPV infection, such as koilocytes, are also commonly seen in CIN. While infection with HPV is needed for development of CIN, most women with HPV infection do not develop HSIL or cancer, HPV is not alone enough causative. [9][10]

Of the over 100 different types of HPV, approximately 40 are known to affect the epithelial tissue of the anogenital area and have different probabilities of causing malignant changes.[11]

Diagnosis

A test for Human Papilloma Virus called the Digene HPV test is highly accurate and serves as both a direct diagnosis and adjuvant to the all-important pap test which is a screening device that allows for an examination of cells but not tissue structure, needed for diagnosis. A colposcopy with directed biopsy is the standard for disease detection. Endocervical brush sampling at the time of pap smear to detect adenocarcinoma and its precursors is necessary along with doctor/patient vigilance on abdominal symptoms associated with uterine and ovarian carcinoma. The diagnosis of CIN or cervical carcinoma requires a biopsy for histological analysis.

Classification

The New Bethesda system reports all gynecologic abnormalities termed "SIL" squamous intraepithelial lesions, arising from all areas of female genital tract, and anal canal of both men and women.

Depending on several factors and the location of the lesion, CIN can start in any of the three stage, and can either progress, or regress.[1] The grade of squamous intraepithelial lesion can vary.

CIN is classified in grades:

| Histology Grade | Corresponding Cytology | Description | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| – | – | Normal cervical epithelium | _normal_squamous_epithelium.jpg) |

| CIN 1 (Grade I) | LSIL[12] | -Represents only mild dysplasia, or abnormal cell growth.[5] -It is confined to the basal 1/3 of the epithelium

-Usually corresponds to infection with HPV and has a high rate of regression back to normal cells and can usually be managed expectantly |

_koilocytosis.jpg) |

| CIN 2/3 | HSIL | -Represents a mix of low- and high-grade lesions not easily differentiated by histology.

-Formerly subdivided into CIN2 and CIN3. -HSIL+ encompasses HSIL, AGC, or cancer | |

| CIN 2 (Grade II) | -Represents a mix of low- and high-grade lesions not easily differentiated by histology.

-Moderate dysplasia confined to the basal 2/3 of the epithelium -CIN 2+ encompasses CIN 2,3, AIS, or cancer |

_CIN2.jpg) | |

| CIN 3 (Grade III) | -Severe dysplasia with undifferentiated neoplastic cells that span more than 2/3 of the epithelium, and may involve the full thickness.

-This lesion may sometimes also be referred to as cervical carcinoma in situ. CIN 3+ encompasses CIN3, adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), or cancer |

_CIN3.jpg) |

College of American Pathology

The College of American Pathology and the American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology came together in 2012 to publish changes in terminology to describe HPV associated squamous lesions of the anogenital tract as LSIL or HSIL as follows below:[13]

CIN 1 is referred to as low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL).

CIN 2 that are p16-negative are referred to as LSIL, and those that are p16-positive are referred to as high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL).

CIN 3 is referred to as HSIL.

Screening

The two screening methods available are the Papanicolau test and testing for Human Papilloma Virus (HPV).

CIN is usually discovered by a screening test, the Papanicolau or "Pap" smear. The purpose of this test is to detect potentially precancerous changes. Pap smear results may be reported using the Bethesda system. The sensitivity and specificity of this test were variable in a systematic review looking at accuracy of the test. [14]

An abnormal Pap smear result may lead to a recommendation for colposcopy of the cervix, during which the cervix is examined under magnification. A biopsy is taken of any abnormal appearing areas.

HPV testing can identify most of the high risk HPV types responsible.[15] HPV screening happents either as a co-test with the Pap test or can be done after a Pap test showing atypical cells, called reflex testing.

Frequency of screening changes based on guidelines from the Society of Lower Genital Tract Disorders (ASCCP).[16] The World Health Organization also has screening and treatment guidelines for precancerous cervical lesions and prevention of cervical cancer.[17]

Prevention

Primary prevention

HPV vaccination is the approach to primary prevention of both CIN and cervical cancer.

Secondary prevention

Appropriate management with monitoring and treatment is the approach to secondary prevention of cervical cancer in cases of persons with CIN.

Treatment

Treatment for CIN 1, which is mild dysplasia, is not recommended if it lasts fewer than 2 years.[18] Usually when a biopsy detects CIN 1 the woman has an HPV infection which may clear on its own within 12 months, and thus it is instead followed for later testing rather than treated.[18] In young women closely following CIN2 lesions also appears reasonable.[19]

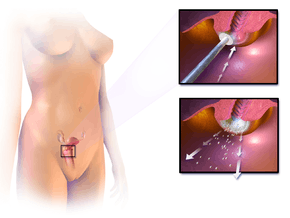

Treatment for higher-grade CIN involves removal or destruction of the abnormal cervical cells by cryocautery, electrocautery, laser cautery, loop electrical excision procedure (LEEP), or cervical conization. The typical threshold for treatment is CIN2+ with exception of young persons and pregnant persons. Therapeutic vaccines are currently undergoing clinical trials. The lifetime recurrence rate of CIN is about 20%, but it isn't clear what proportion of these cases are new infections rather than recurrences of the original infection.

Surgical treatment of CIN lesions is associated with an increased risk of infertility or subfertility, with an odds ratio of approximately 2 according to a case-control study.[20]

The treatment of CIN during pregnancy increases the risk of premature birth.[21] People with HIV and CIN 2+ should be initially managed according to the recommendations for the general population according to the 2012 updated ASCCP consensus guidelines.[22]

Outcomes

It used to be thought that cases of CIN progressed through these stages toward cancer in a linear fashion.[5][23][24]

However most CIN spontaneously regress. Left untreated, about 70% of CIN-1 will regress within one year, and 90% will regress within two years.[25] About 50% of CIN 2 will regress within 2 years without treatment.

Progression to cervical carcinoma in situ (CIS) occurs in approximately 11% of CIN1 and 22% of CIN2. Progression to invasive cancer occurs in approximately 1% of CIN1, 5% in CIN2 and at least 12% in CIN3.[26]

Progression to cancer typically takes 15 years with a range of 3 to 40 years. Also, evidence suggests that cancer can occur without first detectably progressing through these stages and that a high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia can occur without first existing as a lower grade.[1][5][27]

It is thought that the higher risk HPV infections have the ability to inactivate tumor suppressor genes such as the p53 gene and the RB gene, thus allowing the infected cells to grow unchecked and accumulate successive mutations, eventually leading to cancer.[1]

Treatment does not affect the chances of getting pregnant but does increase the risk of second trimester miscarriages.[28]

Epidemiology

Between 250,000 and 1 million American women are diagnosed with CIN annually. Women can develop CIN at any age, however women generally develop it between the ages of 25 to 35.[1] The estimated annual incidence of CIN in the United States among persons who undergo screening is four percent for CIN1 and five percent for CIN 2,3. [29]

History

Changes of the squamous cells of the cervix were historically described as mild, moderate, or severe cervical dysplasia. In 1988, a new terminology system was introduced, the Bethesda system, which was then revised in 1991, 2001, and most recently in 2014. [30][31][32][33]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Mitchell RN (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Saunders Elsevier. pp. 718–721. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- ↑ Wright TC, Schiffman M (February 2003). "Adding a test for human papillomavirus DNA to cervical-cancer screening". The New England Journal of Medicine. 348 (6): 489–90. doi:10.1056/NEJMp020178. PMID 12571255.

- ↑ Kjær SK, Frederiksen K, Munk C, Iftner T (October 2010). "Long-term absolute risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or worse following human papillomavirus infection: role of persistence". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 102 (19): 1478–88. doi:10.1093/jnci/djq356. PMC 2950170. PMID 20841605.

- ↑ Cervical Dysplasia: Overview, Risk Factors

- 1 2 3 4 Agorastos T, Miliaras D, Lambropoulos AF, Chrisafi S, Kotsis A, Manthos A, Bontis J (July 2005). "Detection and typing of human papillomavirus DNA in uterine cervices with coexistent grade I and grade III intraepithelial neoplasia: biologic progression or independent lesions?". European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 121 (1): 99–103. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.11.024. PMID 15949888.

- ↑ DiSaia PJ, Creasman WT. Invasive cervical cancer. In: Clinical Gynecologic Oncology, 7th ed., Mosby Elsevier, Philadelphia 2007. p.55

- ↑ Murthy NS, Mathew A (February 2000). "Risk factors for pre-cancerous lesions of the cervix". European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 9 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1097/00008469-200002000-00002. PMID 10777005.

- ↑ Xi LF, Koutsky LA, Castle PE, Edelstein ZR, Meyers C, Ho J, Schiffman M (December 2009). "Relationship between cigarette smoking and human papilloma virus types 16 and 18 DNA load". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 18 (12): 3490–6. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0763. PMC 2920639. PMID 19959700.

- ↑ Böhmer G, van den Brule AJ, Brummer O, Meijer CL, Petry KU (July 2003). "No confirmed case of human papillomavirus DNA-negative cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or invasive primary cancer of the uterine cervix among 511 patients". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 189 (1): 118–20. PMID 12861148.

- ↑ Zielinski GD, Snijders PJ, Rozendaal L, Voorhorst FJ, van der Linden HC, Runsink AP, de Schipper FA, Meijer CJ (August 2001). "HPV presence precedes abnormal cytology in women developing cervical cancer and signals false negative smears". British Journal of Cancer. 85 (3): 398–404. doi:10.1054/bjoc.2001.1926. PMC 2364067. PMID 11487272.

- ↑ de Villiers EM, Fauquet C, Broker TR, Bernard HU, zur Hausen H (June 2004). "Classification of papillomaviruses". Virology. 324 (1): 17–27. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.033. PMID 15183049.

- ↑ Park J, Sun D, Genest DR, Trivijitsilp P, Suh I, Crum CP (September 1998). "Coexistence of low and high grade squamous intraepithelial lesions of the cervix: morphologic progression or multiple papillomaviruses?". Gynecologic Oncology. 70 (3): 386–91. doi:10.1006/gyno.1998.5100. PMID 9790792.

- ↑ Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Thomas Cox J, et al. The Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology Standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2013; 32:76

- ↑ Nanda K, McCrory DC, Myers ER, Bastian LA, Hasselblad V, Hickey JD, Matchar DB (May 2000). "Accuracy of the Papanicolaou test in screening for and follow-up of cervical cytologic abnormalities: a systematic review". Annals of Internal Medicine. 132 (10): 810–9. PMID 10819705.

- ↑ Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, Killackey M, Kulasingam SL, Cain J, Garcia FA, Moriarty AT, Waxman AG, Wilbur DC, Wentzensen N, Downs LS, Spitzer M, Moscicki AB, Franco EL, Stoler MH, Schiffman M, Castle PE, Myers ER (2012). "American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer". CA: a Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 62 (3): 147–72. doi:10.3322/caac.21139. PMC 3801360. PMID 22422631.

- ↑ "Homepage - ASCCP". www.asccp.org. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ↑ "WHO guidelines for screening and treatment of precancerous lesions for cervical cancer prevention". Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- 1 2 American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, retrieved August 1, 2013 }

- ↑ Tainio, K; Athanasiou, A; Tikkinen, KAO; Aaltonen, R; Cárdenas, J; Hernándes; Glazer-Livson, S; Jakobsson, M; Joronen, K; Kiviharju, M; Louvanto, K; Oksjoki, S; Tähtinen, R; Virtanen, S; Nieminen, P; Kyrgiou, M; Kalliala, I (27 February 2018). "Clinical course of untreated cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 under active surveillance: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 360: k499. PMID 29487049.

- ↑ Spracklen CN, Harland KK, Stegmann BJ, Saftlas AF (July 2013). "Cervical surgery for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and prolonged time to conception of a live birth: a case-control study". Bjog. 120 (8): 960–5. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.12209. PMC 3691952. PMID 23489374.

- ↑ Kyrgiou M, Athanasiou A, Paraskevaidi M, Mitra A, Kalliala I, Martin-Hirsch P, Arbyn M, Bennett P, Paraskevaidis E (July 2016). "Adverse obstetric outcomes after local treatment for cervical preinvasive and early invasive disease according to cone depth: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 354: i3633. doi:10.1136/bmj.i3633. PMC 4964801. PMID 27469988.

- ↑ Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, Katki HA, Kinney WK, Schiffman M, Solomon D, Wentzensen N, Lawson HW (April 2013). "2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors". Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease. 17 (5 Suppl 1): S1–S27. doi:10.1097/LGT.0b013e318287d329. PMID 23519301.

- ↑ Hillemanns P, Wang X, Staehle S, Michels W, Dannecker C (February 2006). "Evaluation of different treatment modalities for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN): CO(2) laser vaporization, photodynamic therapy, excision and vulvectomy". Gynecologic Oncology. 100 (2): 271–5. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.08.012. PMID 16169064.

- ↑ Rapp L, Chen JJ (August 1998). "The papillomavirus E6 proteins". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1378 (1): F1–19. doi:10.1016/s0304-419x(98)00009-2. PMID 9739758.

- ↑ Bosch FX, Burchell AN, Schiffman M, Giuliano AR, de Sanjose S, Bruni L, Tortolero-Luna G, Kjaer SK, Muñoz N (August 2008). "Epidemiology and natural history of human papillomavirus infections and type-specific implications in cervical neoplasia". Vaccine. 26 Suppl 10 (Supplement 10): K1–16. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.05.064. PMID 18847553. 18847553.

- ↑ Section 4 Gynecologic Oncology > Chapter 29. Preinvasive Lesions of the Lower Genital Tract > Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia in:Bradshaw KD, Schorge JO, Schaffer J, Halvorson LM, Hoffman BG (2008). Williams' Gynecology. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 0-07-147257-6.

- ↑ Monnier-Benoit S, Dalstein V, Riethmuller D, Lalaoui N, Mougin C, Prétet JL (March 2006). "Dynamics of HPV16 DNA load reflect the natural history of cervical HPV-associated lesions". Journal of Clinical Virology. 35 (3): 270–7. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2005.09.001. PMID 16214397.

- ↑ Kyrgiou M, Mitra A, Arbyn M, Stasinou SM, Martin-Hirsch P, Bennett P, Paraskevaidis E (October 2014). "Fertility and early pregnancy outcomes after treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 349: g6192. doi:10.1136/bmj.g6192. PMC 4212006. PMID 25352501.

- ↑ Insinga RP, Glass AG, Rush BB. Diagnoses and outcomes in cervical cancer screening: a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004; 191:105.

- ↑ "The 1988 Bethesda System for reporting cervical/vaginal cytologic diagnoses: developed and approved at the National Cancer Institute workshop in Bethesda, MD, December 12-13, 1988". Diagnostic Cytopathology. 5 (3): 331–4. 1989. PMID 2791840.

- ↑ Broder S (1992). "The Bethesda System for Reporting Cervical/Vaginal Cytologic Diagnoses—Report of the 1991 Bethesda Workshop". JAMA. 267 (14): 1892. doi:10.1001/jama.1992.03480140014005.

- ↑ Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, Moriarty A, O'Connor D, Prey M, Raab S, Sherman M, Wilbur D, Wright T, Young N (April 2002). "The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology". JAMA. 287 (16): 2114–9. PMID 11966386.

- ↑ Wilbur DC, Nayar R (December 2015). "Bethesda 2014: improving on a paradigm shift". Cytopathology. 26 (6): 339–42. doi:10.1111/cyt.12300. PMID 26767599.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |