Bus stop

A bus stop is a designated place where buses stop for passengers to board or alight from a bus. The construction of bus stops tends to reflect the level of usage, where stops at busy locations may have shelters, seating, and possibly electronic passenger information systems; less busy stops may use a simple pole and flag to mark the location. Bus stops are, in some locations, clustered together into transport hubs allowing interchange between routes from nearby stops and with other public transport modes to maximise convenience.

Types of service

For operational purposes, there are three main kinds of stops: Scheduled stops, at which the bus should stop irrespective of demand; request stops (or flag stop), at which the vehicle will stop only on request; and hail and ride stops, at which a vehicle will stop anywhere along the designated section of road on request.

Certain stops may be restricted to "discharge/set-down only" or "pick-up only". Some stops may be designated as "timing points", and if the vehicle is ahead of schedule it will wait there to ensure correct synchronization with the timetable. In dense urban areas where bus volumes are high, skip-stops are sometimes used to increase efficiency and reduce delays at bus stops. Fare stages may also be defined by the location of certain stops in distance or zone-based fare collection systems. Sunday stops are close to a church and used only on Sundays.[1]

History

From the 17th to the 19th century, horse drawn stage coaches ran regular services between many European towns, starting and stopping at designated Coaching inns where the horses could be changed and passengers board or alight, in effect constituting the earliest form of bus stop. The Angel Inn, Islington, the first stop on the route from London to York, was a noted example of such an inn. A seat in a Stage coach usually had to be booked in advance.

John Greenwood opened the first bus line in Britain in Manchester in 1824, running a fixed route and allowing passengers to board on request along the way without a reservation. Landmarks such as Public houses, rail stations and road junctions became customary stopping points.

Regular Horse drawn buses started in Paris in 1828 and George Shillibeer started his London horse Omnibus service in 1829. running between stops at Paddington (at a pub - The Yorkshire Stingo) and the Bank of England to a designated route and timetable. By the mid 19th Century guides were available to London bus routes including maps with routes and the main stops [2].

In the UK National National Public Transport Access Node database of all UK stops, developed by the Department of Transport in 2001, stops are classified as marked or custom and usage (i.e. unmarked stops where the driver will stop the vehicle on request). Use of a marked stop may be changed- the bus will always stop, or by request only.

Design

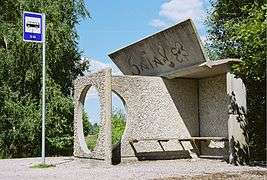

Bus stop infrastructure ranges from a simple pole and sign, to a rudimentary shelter, to sophisticated structures. The usual minimum is a pole mounted flag with suitable name/symbol. Bus stop shelters may have a full or partial roof, supported by a two, three or four sided construction. Modern stops are mere steel and glass/perspex constructions, although in other places, such as rural Britain, stops may be wooden brick or concrete built.[3]

The construction may include small inbuilt seats. The construction may feature advertising, from simple posters, to complex illuminated, changeable or animated displays. Some installations have also included interactive advertising. Design and construction may be uniform to reflect a large corporate or local authority provider, or installations may be more personal or distinctive where a small local authority such as a parish council is responsible for the stop. The stop may include separate street furniture such as a bench, lighting and a trash receptacle.

Individual bus stops may simply be placed on the sidewalk next to the roadway, although they can also be placed to facilitate use of a busway. More complex installations can include construction of a bus turnout or a bus bulb, for traffic management reasons, although use of a bus lane can make these unnecessary. Several bus stops may be grouped together to facilitate easy transfer between routes. These may be arranged in a simple row along the street, or in parallel or diagonal rows of multiple stops. Groups of bus stops may be integral to transportation hubs. With extra facilities such as a waiting room or ticket office, outside groupings of bus stops can be classed as a rudimentary bus station.

Convention is usually for the bus to draw level with the 'flag', although in areas of mixed front and rear entrance buses, such as London, a head stop, and more rarely a tail stop, indicates to the driver whether they should stop the bus with either the rear platform or the drivers cab level with the flag.[4]

In certain areas, the area of road next the bus stop may be specially marked, and protected in law. Often, car drivers can be unaware of the legal implications of stopping or parking in a bus-stop.[5]

In bus rapid transit systems, bus stops may be more elaborate than street bus stops, and can be termed 'stations' to reflect this difference. These may have enclosed areas to allow off-bus fare collection for rapid boarding, and be spaced further apart like tram stops. Bus stops on a bus rapid transit line may also have a more complex construction allowing level boarding platforms, and doors separating the enclosure from the bus until ready to board.

.jpg)

A bus shelter in India

A bus shelter in India Wooden bus stop shelter in Sõmerpalu Parish, Estonia

Wooden bus stop shelter in Sõmerpalu Parish, Estonia

Bus Rapid Transit shelter for the RIT system in Curitiba, Brazil, known as "tubo" (tube)

Bus Rapid Transit shelter for the RIT system in Curitiba, Brazil, known as "tubo" (tube)

Information

Public facing information

Most bus stops are identified with a metal sign attached to a pole or light standard. Some stops are plastic strips strapped on to poles and others involve a sign attached to a bus shelter. The signs are often identified with a picture of a bus and/or with the words "bus stop" (or similar in non-English-speaking places).

The bus stop "flag" (a panel usually projecting from the top of a bus stop pole) will sometimes contain the route numbers of all the buses calling at the stop, optionally distinguishing frequent, infrequent, 24-hour, and night services. The flag may also show the logo of the dominant bus operator, or the logo of a local transit authority with responsibility for bus services in the area. Additional information may include an unambiguous, unique name for the stop, and the direction/common destination of most calling routes.

Bus stops will often include timetable information, either the full timetable, or for busier routes, the times or frequency that a bus will call at the specific stop. Route maps and tariff information may also be provided, and telephone numbers to relevant travel information services.

The stop may also incorporate, or have nearby, real time information displays with the arrival times of the next buses. Increasingly, mobile phone technology is being referenced on more remote stops, allowing the next bus times to be sent to a passenger's handset based on the stop location and the real time information. Automated ticket machines may be provided at busy stops.

Data model

Modern passenger information systems and journey planners require a detailed digital representation of stops and stations. The CEN Transmodel data model, and the related IFOPT data interchange standard, define how transport systems, including bus stops, should be described for use in computer models. In Transmodel, a single bus stop is modeled as a "Stop Point", and a grouping of nearby bus stops as a "Stop Area" or "Stop Place". The General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS) standard, originally developed by Google and TriMet,[6] defines a simple and widely used data interchange standard for public transport schedules. GTFS also includes a table of stop locations which for each stop gives a name, identifier, location, and identification with any larger station that the stop may be a part of.[7] OpenStreetMap also has a modelling standard for bus stops.[8]

The United Kingdom has collected a complete database of its public transport access points, including bus stops, into the National Public Transport Access Nodes (NaPTAN) database with details of 350,000 nodes and which is available as open Data from data.gov.uk.[9]

Safety

Bus stops enhance passenger safety in a number of ways:

- Bus stops prevent passengers from trying to board or alight in hazardous situations such as at intersections or where a bus is turning and is not using the curb lane.

- A bus driver cannot be expected to continuously look for intending passengers. A bus stop means that the driver only needs to look for intending passengers at the approach to each bus stop.

- Having bus stops requires passengers to group themselves prior to boarding, which reduces time spent at boarding.

- At night, when passenger numbers are lower, restrictions are sometimes relaxed and passengers may be allowed to exit the bus anywhere within reason.[10]

- Bus turnouts, or lay-bys, allow buses to stop without impeding the flow of traffic on the main roadway

Regulation

Some jurisdictions have introduced particularised legislative controls to foster safer bus stop design and management. The State of Victoria, Australia, for example, has enacted a Bus Safety Act which contains performance-based duties of care[11] which apply to all industry participants who are in a position to influence the safety of bus operations - what is called the "chain of responsibility". The safety duties apply to all bus services, both commercial and non-commercial, and to all buses regardless of seating capacity. Breach of the duty is a serious criminal offence which carries a heavy penalty.

The primary duty holder under the Bus Safety Act is the operator of the bus service, as the person who has effective responsibility and control over the whole operation.[12] However, the Act also contains a safety duty covering "people with responsibility for bus stops", including people who design, build, or maintain the stop, plus those who decide on its location.[13]

This duty was introduced in response to research showing that the most serious hazard associated with bus travel occurs when passengers, especially children, are crossing the road after alighting from the bus. The location and layout of a bus stop is therefore a factor in the level of risk.[14]

Safety duties are also imposed by the Bus Safety Act on a range of other people including -

- "bus safety workers" including drivers, schedulers who set bus timetables, and mechanics and testers who repair or assess vehicle safety[15]

- "procurers" - people who procure the bus service, known as the "customer" in the commercial charter sector.[16]

All of these persons can clearly affect bus safety. They are required by the Bus Safety Act to ensure that, in carrying out their activities, they eliminate risks to health and safety if 'practicable' - or work to reduce those risks 'so far as is reasonably practicable'. This familiar practicability formula is borrowed from Victoria's Rail Safety Act (and a subsequent national model Rail Safety Bill) and the Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004.

Research

Many transit agencies have developed guidelines for preferred bus stop spacing. In most US cities, however, the typical bus stop spacing is between 650 and 900 feet (200–275 m), well below the optimal.

Bus stop capacity is often an important consideration in the planning of bus stops serving multiple routes within urban centers. Limited capacity may mean buses queue up behind each other at the bus stop, which can cause traffic blockages or delays. Bus stop capacity is typically measured in terms of buses/hour that can reliably use the bus stop. The main factors that affect bus stop capacity are:

- Number of loading areas (or number of buses that can stop at one time)

- Average dwell time (How much time it takes a bus to load/unload passengers)

- G/C ratio of nearby traffic signal (green time / cycle length)

- Clearance time (time it takes bus to re-enter the traffic stream)

Detailed procedures for calculating bus stop capacity and bus lane capacity using skip stops are outlined in Part 4 of the Transit Capacity and Quality of Service Manual, published by the US Transportation Research Board.

Transit agencies are increasingly looking at consolidation of possibly previously haphazardly placed bus stops as a way to improve service cheaply and easily. Bus stop consolidation evaluates the bus stops along an established bus route and develops a new pattern for optimal bus stop placement. Bus stop consolidation has been proven to improve operating efficiency and ridership on bus routes.

Fake bus stops

Some nursing homes have built fake, imitation bus stops for their residents who have dementia.[17] Some of these bus stops are even fitted with outdated advertisements and timetables – 30 years outdated.[17] The residents will sit at the bus stop waiting for a bus to take them to their imagined destination.[17] After some time, a staff member comes to escort the clients back to the home.[17]

In popular culture

Bus stops are common tropes in popular culture. In 1956 there was a Marilyn Monroe film called Bus Stop. A famous scene in the movie Forrest Gump takes place at a bus stop and almost all episodes of South Park series start by presenting the main characters in a bus stop.

In Japanese culture, the movie My Neighbor Totoro featured a bus stop, both for ordinary buses and a cat bus. The opening scene of the anime Air shows the main character getting off at a bus stop. The Japanese movie Summer Wars features a rural bus stop.

Renowned rabbis have taught lessons in Judaism from their interaction and experience with bus stops.[18][19][20][21][22][23]

See also

References

- ↑ Andrew-Gee, Eric (7 May 2015). "Sunday streetcar stops near churches to be shuttered in June". Toronto Star. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ↑ Reynolds, James (1853). Reynolds's Cab Fares and Omnibus Guide, ... with maps. London, England: James REYNOLDS, Bookseller.

- ↑ "Bus stop in Western Isles". wordpress.com. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ↑ "Save BIG with $9.99 .COMs from GoDaddy!". Go Daddy. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ↑ Nottingham city transport Archived July 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Bus Lanes and Bus Stops - what's the problem?

- ↑ "Pioneering Open Data Standards: The GTFS Story". beyondtransparency.org. Retrieved 2017-05-11.

- ↑ "stops.txt File | Static Transit | Google Developers". Google Developers. Retrieved 2017-05-11.

- ↑ "Bus Stop". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 2010-03-25.

- ↑ "National Public Transport Access Nodes (NaPTAN)". data.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 2010-03-25.

- ↑ http://www.vestische.de/halten-auf-wunsch/articles/halten-auf-wunsch.html (Example for one such regulation, in German)

- ↑ Bus Safety Act 2009, Part 3.

- ↑ Bus Safety Act 2009, section 15.

- ↑ Bus Safety Act 2009, section 18.

- ↑ See Improving Bus Safety in Victoria, a discussion paper published by the Department of Transport in May 2009.

- ↑ Bus Safety Act 2009, section 17.

- ↑ Bus Safety Act 2009, section 16.

- 1 2 3 4 Paulick, Jane. "Bus-Stops at Old People's Homes Take Patients for a Ride". Deutsche Welle. June 6, 2008. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ↑ B. C. Glaberson (1 June 1999). The life and times of Reb Rephoel Soloveitchik of Brisk. Feldheim. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-58330-361-0. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ↑ Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach Archived 2010-07-31 at the Wayback Machine., Yated Neeman

- ↑ Nisson Wolpin (2002). Torah leaders: a treasury of biographical sketches collected from the pages of the Jewish Observer. Mesorah Publications in conjunction with Agudath Israel of America. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-57819-773-6. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ↑ A. L. Scheinbaum (February 1998). Peninim on the Torah. Peninim Publications in conjunction with "The Living Memorial," a project of the Hebrew Academy of Cleveland. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-9635120-6-2. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ↑ Yonason Rosenblum (2000). Rav Dessler: the life and impact of Rabbi Eliyahu Eliezer Dessler the Michtav m'Eliyahu. Mesorah. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-57819-506-0. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ↑ "ArtScroll.com". www.artscroll.com. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Look up Bus stop in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Bus stop design guidance from the National Association of City Transportation Officials Transit Street Design Guide