Bright's disease

| Bright's disease | |

|---|---|

| |

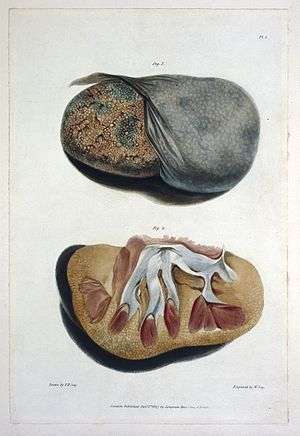

| Diseased kidney from Richard Bright's Reports of Medical Cases Longman, London (1827–1831). Wellcome Library, London | |

| Classification and external resources |

Bright's disease is a historical classification of kidney diseases that would be described in modern medicine as acute or chronic nephritis.[1] It was characterized by swelling, the presence of albumin in the urine and was frequently accompanied by high blood pressure and heart disease.

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms and signs of Bright's disease were first described in 1827 by the English physician Richard Bright, after whom the disease was named. In his Reports of Medical Cases,[2] he described 25 cases of dropsy (edema) which he attributed to kidney disease. Symptoms and signs included: inflammation of serous membranes, hemorrhages, apoplexy, convulsions, blindness and coma.[3][4] Many of these cases were found to have albumin in their urine (detected by the spoon and candle-heat coagulation), and showed striking morbid changes of the kidneys at autopsy.[5] The triad of dropsy, albumin in the urine and kidney disease came to be regarded as characteristic of Bright's disease.[3]

Subsequent work by Bright and others indicated an association with cardiac hypertrophy, which was attributed by Bright to stimulation of the heart. Subsequent work by Frederick Akbar Mahomed showed that a rise in blood pressure could precede the appearance of albumin in the urine, and the rise in blood pressure and increased resistance to flow was believed to explain the cardiac hypertrophy.[4]

It is now known that Bright's disease is due to a wide range of diverse kidney diseases;[1][5][6] thus, the term Bright's disease is retained strictly for historical application.[7] The disease was diagnosed frequently in patients with diabetes;[4] at least some of these cases would probably correspond to a modern diagnosis of diabetic nephropathy.

Treatment

Bright's disease was historically treated with warm baths, blood-letting, squill, digitalis, mercuric compounds, opium, diuretics, laxatives,[2][8] and dietary therapy, including abstinence from alcoholic drinks, cheese and red meat. Arnold Ehret was diagnosed with Bright's disease and pronounced incurable by 24 of Europe's most respected doctors; he designed The Mucusless Diet Healing System, which apparently cured his illness. William Howard Hay, MD had the illness and, it is claimed, cured himself using the Hay diet.[9]

Historical accounts attributing deaths to Bright's disease

Legendary Old West lawman Bass Reeves' death was attributed to this disease.[10]

British civil engineers Isambard Kingdom Brunel and Robert Stephenson died on 20 September 1859, and 12 October 1859, respectively.[11][12][13]

Frederick William Faber died on 26 September 1863.

George-Étienne Cartier, Founding Father of the Confederation of Canada, died on 20 May 1873.

Rowland Hussey Macy Sr., an American businessman and founder of the department store chain R.H. Macy and Company died on 29 March 1877 in Paris.

The famous dwarf Commodore Nutt died in New York on May 25, 1881.

The Impressionist painter Mary Cassatt's sister Lydia died in 1882.[14]

Alice Hathaway Lee Roosevelt, first wife of Theodore Roosevelt, died on 14 February 1884.[15]

American tennis pioneer Mary Ewing Outerbridge died at the age of 34, on May 3, 1886.

The poet Emily Dickinson died May 15, 1886.

Chester Alan Arthur, 21st President of the United States, died November 18, 1886.

Swedish-American mechanical engineer John Ericsson, most famous for designing USS Monitor, died on March 8, 1889.[16]

Famed gunfighter Luke Short died in September 8, 1893.

Union general Francis Barlow, who had played an important role in the American Civil War, died on January 11, 1896.

Soldier and ornithologist Charles Bendire died in 1897.[17]

Warren S. Johnson, founder of Johnson Controls, died on December 5, 1911, at the age of 64.

James S. Sherman, was Vice President of the United States from 1909 until his death from Bright's disease in 1912.

Ellen Axson Wilson, first wife of Woodrow Wilson, died on 6 August 1914.[18]

Woodsman Louis "French Louie" Seymour died on February 28, 1915.

John Bunny, an American actor and one of the first comic stars of the early motion picture era, died on April 26, 1915.

Australian cricketer Victor Trumper died at age 37, in June 1915.

Booker T. Washington, founder and principal of Tuskegee University, died in November 1915.

Charles Sumner Sedgwick, a prominent architect based in Minneapolis, Minnesota, died in 1922.

Baseball Hall of Famer Ross Youngs died on October 22, 1927.

Master of Science Fiction Horror, Howard Phillips “H. P.” Lovecraft, died from a combination of cancer and Bright’s Disease on March 15, 1937, at the age of 46.

Albert Carl "Al" Ringling (1852–1916), eldest of the Ringling brothers, died of Bright's disease at the age of 63 in Wisconsin.[19]

References

- 1 2 Cameron, J. S. (14 October 1972). "Bright's Disease Today: The Pathogenesis and Treatment of Glomerulonephritis—I". British Medical Journal. 4 (5832): 87–90. doi:10.1136/bmj.4.5832.87. ISSN 0007-1447. PMC 1786202. PMID 4562073.

- 1 2 Bright, R (1827–1831). Reports of Medical Cases, Selected with a View of Illustrating the Symptoms and Cure of Diseases by a Reference to Morbid Anatomy, vol. I. London: Longmans.

- 1 2 Millard, Henry B. (1 January 1884). A treatise on Bright's disease of the kidneys; its pathology, diagnosis, and treatment . New York, W. Wood & Company.

- 1 2 3 "A treatise on Bright's disease and diabetes : with especial reference to pathology and therapeutics". archive.org. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- 1 2 Peitzman, Steven J. (1 January 1989). "From Dropsy to Bright's Disease to End-Stage Renal Disease". The Milbank Quarterly. 67: 16–32. doi:10.2307/3350183. JSTOR 3350183. PMID 2682170.

- ↑ Wolf G (2002). "Friedrich Theodor von Frerichs (1819–1885) and Bright's disease". American Journal of Nephrology. 22 (5–6): 596–602. doi:10.1159/000065291. PMID 12381966.

- ↑ Peitzman SJ (1989). "From dropsy to Bright's disease to end-stage renal disease". The Milbank quarterly. 67 Suppl 1: 16–32. doi:10.2307/3350183. PMID 2682170.

- ↑ Saundby, Robert (22 October 2013). Lectures on Bright's Disease. Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 9781483195360.

- ↑ Gilman, Goldwin Smith Professor of Human Studies Sander L.; Gilman, Sander L. (23 January 2008). Diets and Dieting: A Cultural Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 9781135870683.

- ↑ "Was the Real Lone Ranger a Black Man?". history.com.

- ↑ Bailey, Michael R., ed. (2003). Robert Stephenson; The Eminent Engineer. Ashgate. p. XXIII. ISBN 0-7546-3679-8.

- ↑ Rolt 1984, pp. 318–319.

- ↑ Ross 2010, pp. 242–243.

- ↑ Mancoff, Debra (1998). Mary Cassatt: Reflections of Women's Lives. London: Frances Lincoln. p. 15.

- ↑ Commire, Anne (1999). Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Yorkin Publications.

- ↑ Church, W.C. (1892). The Life of John Ericsson. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co. pp. 320–323.

- ↑ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael (2003). Whose Bird? Common Bird Names and the People They Commemorate. New Haven, London: Yale University Press. pp. 47–48. ISBN 0-300-10359-X. LCCN 2003113608.

- ↑ "Ellen Wilson Biography :: National First Ladies' Library". www.firstladies.org.

- ↑ "Al. Ringling Dead. Veteran Circus Man Stricken with Bright's Disease In Wisconsin" (PDF). New York Times. January 2, 1916. Retrieved 2018-10-10.