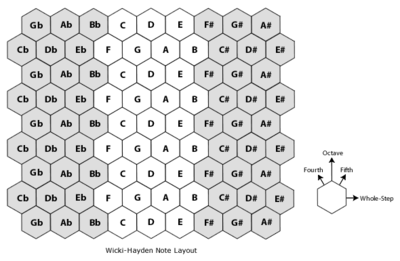

Wicki-Hayden note layout

The Wicki-Hayden note layout is a musical keyboard layout that differs from the traditional layout.

History

The Wicki-Hayden (W/H) layout was initially conceived by Kaspar Wicki for the bandoneon and patented in 1896.[1] It was independently conceived and refined by Brian Hayden, a concertina player, who patented it again a century later, in 1986. This layout is popular with concertina players, since it places all the notes of the major scale under the fingers without requiring hand movement.

Jim Plamondon later discovered the W/H layout while searching for an optimal keyboard layout to use in the electronic musical instrument he was designing. He publicized its benefits widely through the web and through his company Thumtronics (which failed to achieve commercial success). He hoped to use the web and "word-of-finger" contacts to reach people interested in novel music instruments. As he envisioned, novel music instrument hobbyists have become interested in the features and advantages of Wicki-Hayden instruments and have begun to make their own, at first manually, and then by adapting commercially available instruments.

Relationship to the standard piano keyboard

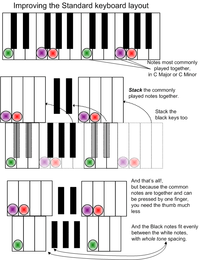

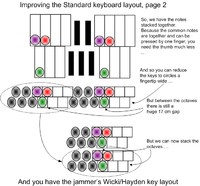

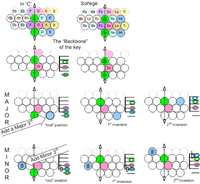

The traditional keyboard has 7 white keys (CDEFGAB) that repeat with each octave. These can be grouped into the first 3 keys (CDE) and the following 4 keys (FGAB). The critical change is to stack the 4 white notes (FGAB) just above the 3 notes (CDE), as shown in the diagrams to the right and left. This seemingly minor change in placement has surprising and profound consequences in the resulting note layout.

Advantages

In western music’s preeminent major scale, the important notes are the white keys on a piano. However, their linear layout presents ergonomic challenges:

- Keys are far apart and therefore slow to play, as the hands have to move a considerable distance.

- The intervals between neighboring white keys are irregular: sometimes a whole step (C-D) and at others a half step (E-F).

- The combination of white and black keys and the pitch-to-key distance and vector is irregular.

- New players must watch the keyboard, instead of reading the score.

- The keys that sound worst when played together are right next to each other, increasing the chance of mistakes.

- Both hands have different fingerings. At the right hand the thumb shows to the lower tones, at the left hand it shows to the higher tones.

The W/H layout avoids these problems:

- Commonly played notes that are separated by as much as 12 cm on the piano, are grouped much closer together.

- The uniform isomorphic layout makes fingering patterns consistent, so only one fingering must be learned, instead of twelve for each hand (24 patterns in total) as on the piano.

- The normally troublesome black keys move out of the way and are split into two groups: a "sharp" and a "flat" section.

- Instead of mistakes sounding bad, they sound consonant, allowing for easy jamming.

- Because on concertinas and bandoneons both hands have separated button boards, instrument makers can build mirrored button boards, so that the left hand has the same fingering as the right hand. In this case the left hand can immediately play the same melody as the right hand.

To summarize, the Wicki/Hayden layout moves the keys to where they are more reachable, useful and less prone to mistakes.

Right: Some of the chords playable

Some studies and the consonance/dissonance diagram to the right indicate there may be strong parallels to the way the brain hears music.[2][3]

Disadvantages

The Wicki/Hayden system strongly encourages consonant play within a given key signature, which paradoxically may make players less innovative.

A proposed problem with the Wicki/Hayden system is that the keys are not in chromatic order. It is argued from this that playing impromptu ornamental flourishes and accidental passing tones are less intuitive than on chromatically ordered key arrangements. In the common practice of much modern western music, especially improvised music like jazz, almost every chromatic note is commonly used within any key signature. It initially was argued that the less-intuitive ergonomic access to chromatic intervals would prove to be a detriment to performing musical styles that make heavier use of dissonance. However, experimental players of the layout report the isomorphism provides a firmer framework to choose desired sounds and effects.[4]

Jammer players have found that many classical piano exercises are optimized for the piano layout, and therefore are more challenging to learn to play on the jammer, e.g. the early Hanon Exercises (see: The Virtuoso Pianist in 60 Exercises). They note, however, that once learned, the exercises generalize to all keys, which does not happen on the standard keyboard: Hanon Exercises are significantly harder to play in keys other than C.

Experimentally, advanced jammer players find that they can adopt a fingering that places the fingers on the keys so as to considerably reduce the distance the hands and fingers move and benefiting per Fitts's law to provide faster playing.

Software

- Relayer: an app (Windows and OS X) that enables musicians who play the QWERTY computer keyboard, or the AXiS-49 MIDI controller, to play in a wide variety of isomorphic note layouts (including the Wicki-Hayden). It supports both standard tunings as well as microtonal.

- Qwertonic: site with Java, Flash, and PC applications enables children and non-musicians, to play their PC keyboard as a Wicki/Hayden instrument, with three octaves of 12 equal-tempered pitches.

Instruments using the layout

- Hayden Duet System Concertinas, see The Hayden duet system concertina - Resource List

- Electronic MIDI instruments that use this layout are called jammers, since they are excellent for jamming with other musicians. Hand-made jammer makers are to be found at DIYKeyboard and MusicScienceGuy .

- Apple iPhone/iPod/iPad applications: iJammer, HexJam and Musix convert iOS devices into concertinas and jammers.

- On Android, there is IsoKeys and the opensource Hexiano, which both support the Jammer layout.

Color schemes

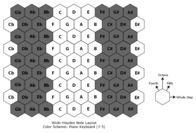

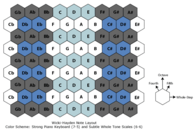

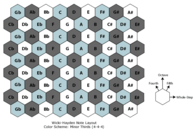

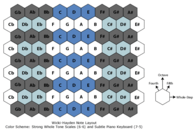

These are some possible color schemes that can be used with the Wicki/Hayden layout:

Traditional Piano Keyboard (7-5) Color Scheme

Traditional Piano Keyboard (7-5) Color Scheme Strong Piano (7-5) and Subtle Whole Tone Scale (6-6) Color Scheme

Strong Piano (7-5) and Subtle Whole Tone Scale (6-6) Color Scheme Minor Thirds Color Scheme (4-4-4)

Minor Thirds Color Scheme (4-4-4) Whole Tone Scale (6-6) Color Scheme

Whole Tone Scale (6-6) Color Scheme Strong Whole Tone Scale (6-6) and Subtle Piano (7-5) Color Scheme

Strong Whole Tone Scale (6-6) and Subtle Piano (7-5) Color Scheme Major Thirds Color Scheme (3-3-3-3)

Major Thirds Color Scheme (3-3-3-3)

The color schemes above divide the 12 basic notes of the chromatic scale into groups in different ways:

- Piano (7-5): two asymmetrical groups of 7 (white keys) and 5 (black keys)

- Whole Tone Scale (6-6): two symmetrical groups of notes a major second apart (6 notes per group)

- Minor Thirds (4-4-4): three symmetrical groups of notes a minor third apart (4 notes per group)

- Major Thirds (3-3-3-3): four symmetrical groups of notes a major third apart (3 notes per group)

(Note that the whole tone scale (6-6) color scheme by itself is not very practical for the Wicki-Hayden layout since this pattern is already the basis for the physical layout of the keys—each row is a whole tone scale. It is more useful when combined with the piano (7-5) color scheme, particularly for better orientation along the vertical axis.)

See also

- The Jankó keyboard uses a similar whole-tone-scale 6-plus-6 based layout

- The Melodic/Harmonic table note-layout explained

- Isomorphic keyboard

- The Generalized keyboard

References

- ↑ Maria Dunkel (1987). Bandonion und Konzertina. E. Katzbichler. p. 92. - 1896 erhält Kaspar Wicki, Münster/Schweiz, das Patent No. 99324 für seine „Neuartige Tastatur" (siehe Tabelle 20), die eine indirekte Anwendung des Jankö -Systems auf das Bandonion darstellt

- ↑ Paine, G.; Stevenson, I.; Pearce, A. (2007). "The Thummer Mapping Project (ThuMP)" (PDF). Proceedings of the 7th international conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME07): 70–77.

- ↑ Bergstrom, T.; Karahalios, K.; Hart, J. C. (2007). "Isochords: visualizing structure in music". Proceedings of Graphics Interface 2007.

- ↑ http://www.musicscienceguy.com/2012/02/playing-the-jammer-part-1.html

External links

- Patent number GB2131592 (B), An Arrangement of Notes for Musical Instruments.

- Qwertonic, UK site containing Java/Flash applications to enable users to play their alpha-numeric keyboard to sound 12 equal tempered pitches using Wicki/Hayden layout.

- concertina.net

- www.altkeyboards.com Specializes in documenting new musical instruments.