Brand awareness

Brand awareness refers to the extent to which customers are able to recall or recognise a brand.[1] Brand awareness is a key consideration in consumer behavior, advertising management, brand management and strategy development. The consumer's ability to recognise or recall a brand is central to purchasing decision-making. Purchasing cannot proceed unless a consumer is first aware of a product category and a brand within that category. Awareness does not necessarily mean that the consumer must be able to recall a specific brand name, but he or she must be able to recall sufficient distinguishing features for purchasing to proceed. For instance, if a consumer asks her friend to buy her some gum in a "blue pack", the friend would be expected to know which gum to buy, even though neither friend can recall the precise brand name at the time.

Different types of brand awareness have been identified, namely brand recall and brand recognition. Key researchers argue that these different types of awareness operate in fundamentally different ways and that this has important implications for the purchase decision process and for marketing communications. Brand awareness is closely related to concepts such as the evoked set and consideration set which describe specific aspects of the consumer's purchase decision. Consumers are believed to hold between three and seven brands in their consideration set across a broad range of product categories. [2] Consumers will normally purchase one of the top three brands in their consideration set.

Brand awareness is a key indicator of a brand's competitive market performance. Given the importance of brand awareness in consumer purchasing decisions, marketers have developed a number of metrics designed to measure brand awareness and other measures of brand health. These metrics are collectively known as Awareness, Attitudes and Usage (AAU) metrics.

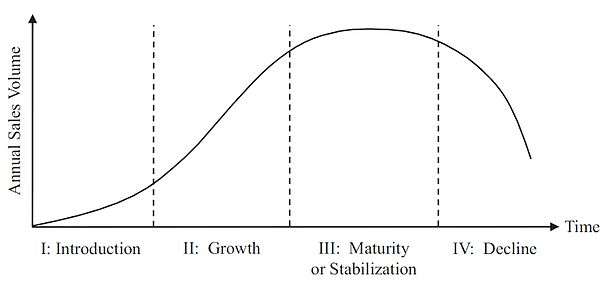

To ensure a product or brand's market success, awareness levels must be managed across the entire product life-cycle - from product launch through to market decline. Many marketers regularly monitor brand awareness levels, and if they fall below a predetermined threshold, the advertising and promotional effort is intensified until awareness returns to the desired level.

Importance of brand awareness

Brand awareness is related to the functions of brand identities in consumers’ memory and can be measured by how well the consumers can identify the brand under various conditions.[3] Brand awareness is also central to understanding the consumer purchase decision process. Strong brand awareness can be a predictor of brand success.[4] It is an important measure of brand strength or brand equity and is also involved in customer satisfaction, brand loyalty and the customer's brand relationships .[5]

Brand awareness is a key indicator of a brand's market performance. Every year advertisers invest substantial sums of money attempting to improve a brand's overall awareness levels. Many marketers regularly monitor brand awareness levels, and if they fall below a predetermined threshold, the advertising and promotional effort is intensified until awareness returns to the desired level. Setting brand awareness goals/ objectives is a key decision in marketing planning and strategy development.

Brand awareness is one of major brand assets that adds value to the product, service or company.[6] Investments in building brand awareness can lead to sustainable competitive advantages, thus, leading to long-term value.[6]

| Rank | Logo | Brand | Value ($m) |

| 1 | Apple | 178,119 | |

| 2 | 133,252 | ||

| 3 | Coca-Cola | 73,102 | |

| 4 | Microsoft | 72,795 | |

| 5 | Toyota | 53,580 | |

| 6 | IBM | 52,850 | |

| 7 | Samsung | 51,808 | |

| 8 | Amazon | 50,338 | |

| 9 | Mercedes-Benz | 43,400 | |

| 10 | G.E. | 43,130 |

Types of brand awareness

Marketers typically identify two distinct types of brand awareness; namely brand recall (also known as unaided recall or occasionally spontaneous recall) and brand recognition (also known as aided brand recall).[8] These types of awareness operate in entirely different ways with important implications for marketing strategy and advertising.

Brand recall

Brand recall is also known as unaided recall or spontaneous recall and refers to the ability of the consumers to correctly elicit a brand name from memory when prompted by a product category.[3] Brand recall indicates a relatively strong link between a category and a brand while brand recognition indicates a weaker link. When prompted by a product category, most consumers can only recall a relatively small set of brands, typically around 3–5 brand names. In consumer tests, few consumers can recall more than seven brand names within a given category and for low-interest product categories, most consumers can only recall one or two brand names.[9]

Research suggests that the number of brands that consumers can recall is affected by both individual and product factors including; brand loyalty, awareness set size, situational, usage factors and education level.[10] For instance, consumers who are involved with a category, such as heavy users or product enthusiasts, may be able to recall a slightly larger set of brand names than those who are less involved.

Brand recognition

Brand recognition is also known as aided recall and refers to the ability of the consumers to correctly differentiate the brand when they come into contact with it. This does not necessarily require that the consumers identify the brand name. Instead, it means that consumers can recognise the brand when presented with it at the point-of-sale or after viewing its visual packaging.[11] In contrast to brand recall, where few consumers are able to spontaneously recall brand names within a given category, when prompted with a brand name, a larger number of consumers are typically able to recognise it.

Top-of-mind awareness

Consumers will normally purchase one of the top three brands in their consideration set. This is known as top-of-mind awareness.[12] Consequently, one of the goals for most marketing communications is to increase the probability that consumers will include the brand in their consideration sets.

By definition, top-of-mind awareness is "the first brand that comes to mind when a customer is asked an unprompted question about a category."[13] When discussing top-of-mind awareness among larger groups of consumers (as opposed to a single consumer), it is more often defined as the "most remembered" or "most recalled" brand name(s).[14]

A brand that enjoys top-of-mind awareness will generally be considered as a genuine purchase option, provided that the consumer is favourably disposed to the brand name.[15] Top-of-mind awareness is relevant when consumers make a quick choice between competing brands in low-involvement categories or for impulse type purchases.[16]

Marketing implications of brand awareness

Clearly brand awareness is closely related to the concepts of the evoked set (defined as the set of brands that a consumer can elicit from memory when contemplating a purchase) and the consideration set (defined as the “small set of brands which a consumer pays close attention to when making a purchase decision”).[17] One of the advertising's central roles is to create both brand awareness and brand image, in order to increase the likelihood that a brand is included in the consumer's evoked set or consideration set and regarded favourably. [18]

Consumers do not learn about products and brands from advertising alone. When making purchase decisions, consumers acquire information from a wide variety of sources in order to inform their decisions. After searching for information about a category, consumers may become aware of a larger number of brands which collectively are known as the awareness set.[19] Thus, the awareness set is likely to change as consumers acquire new information about brands or products. A review of empirical studies in this area suggests that the consideration set is likely to be at least three times larger than the evoked set.[20] Awareness alone is not sufficient to trigger a purchase, consumers also need to be favourably disposed to a brand before it will be considered as a realistic purchase option.

The process of moving consumers from brand awareness and a positive brand attitude through to the actual sale is known as conversion. [21] While advertising is an excellent tool for creating awareness and brand attitude, it usually requires support from other elements in the marketing program to convert attitudes into actual sales.[22] Other promotional activities, such as telemarketing, are vastly superior to advertising in terms of generating sales. Accordingly, the advertising message might attempt to drive consumers to direct sales call centres as part of an integrated communications strategy. [23] Many different techniques can be used to convert interest into sales including special price offers, special promotional offers, attractive trade-in terms or guarantees.

.jpg)

Percy and Rossiter (1992) argue that the two types of awareness, namely brand recall and brand recognition, operate in fundamentally different ways in the purchase decision. For routine purchases such as fast moving consumer goods (FMCG), few shoppers carry shopping lists. For them, the presentation of brands at the point-of-sale acts as a visual reminder and triggers category need. In this case, brand recognition is the dominant mode of awareness. For other purchases, where the brand is not present, the consumer first experiences category need then searches memory for brands within that category. Many services, such as home help, gardening services, pizza delivery fall into this category. In this case, the category need precedes brand awareness. Such purchases are recall dominant, and the consumer is more likely to select one of the brands elicited from memory.[24] When brand recall is dominant, it is not necessary for consumers to like the advertisement, but they must like the brand. In contrast, consumers should like the ad when brand recognition is the communications objective. [25]

The distinction between brand recall and brand recognition has important implications for advertising strategy. When the communications objectives depend on brand recognition, the creative execution must show the brand packaging or a recognisable brand name. However, when the communications objectives rely on brand recall, the creative execution should encourage strong associations between the category and the brand.[26] Advertisers also use jingles, mnemonics and other devices to encourage brand recall.

Brand dominance occurs when, during brand recall tests, most consumers can name only one brand from a given category.[27] Brand dominance is defined as an individual’s selection of only certain brand names in a related category during a brand recall procedure.[27] While brand dominance might appear to be a desirable goal, overall dominance can be a double-edged sword.

.jpg)

A brand name that is well known to the majority of people or households is also called a household name [28] and may be an indicator of brand success. Occasionally a brand can become so successful that the brand becomes synonymous with the category. For example, British people often talk about "Hoovering the house" when they actually mean "vacuuming the house." (Hoover is a brand name). When this happens, the brand name is said to have "gone generic." [29] Examples of brands becoming generic abound; Kleenex, Cellotape, Nescafe, Aspirin and Panadol. When a brand goes generic, it can present a marketing problem because when the consumer requests a named brand at the retail outlet, they may be supplied with a competing brand. For example, if a person enters a bar and requests "a rum and Coke," the bartender may interpret that to mean a "rum and cola-flavoured beverage," paving the way for the outlet to supply a cheaper alternative mixer. In such a scenario, Coca-Cola Ltd, who after investing in brand building for more than a century, is the ultimate loser because it does not get the sale.

Measuring brand awareness

Just as different types of brand awareness can be identified, there are a variety of methods for measuring awareness. Typically, researchers use surveys, carried out on a sample of consumers asking about their knowledge of the focus brand or category.

Two types of recall test are used to measure brand awareness:[30]

- Unaided recall tests: where the respondent is presented with a product category and asked to nominate as many brands as possible. Thus, the unaided recall test provides the respondent with no clues or cues. Unaided recall tests are used to test for brand recall.

- Aided recall test: where the respondent is prompted with a brand name and asked whether they have seen it or heard about it. In some aided recall tests, the respondent might also be asked to explain what they know about the brand e.g. to describe package, colour, logo or other distinctive features. Aided recall tests are used to test for brand recognition.

- Other brand-effects tests: In addition, to recall tests, brand research often employs a battery of tests, such as brand association tests, brand attitude, brand image, brand dominance, brand value, brand salience and other measures of brand health. Although these tests do not explicitly measure brand awareness, they provide general measures of brand health and often are used in conjunction with brand recall tests.

To measure brand salience, for example, researchers place products on a shelf in a supermarket, giving each brand equal shelf space. Consumers are shown photographs of the shelf display and ask consumers to name the brands noticed. The speed at which consumers nominate a given brand is an indicator of brand's visual salience. This type of research can provide valuable insights into the effectiveness of packaging design and brand logos. [31]

A number of commercial research firms (e.g. Interbrand,[32] Millward-Brown,[33] Nielsen (Asia) [34]) monitor brand effects for key international brands and the topline survey findings are widely published in business press, trade press and online. It is worth noting that these commercially compiled lists are not popularity contests, but use clearly articulated methodologies to compile lists based on consumer responses collected in structured research. However, these listings use a variety of metrics, so the results are not directly comparable and it cannot be assumed that they measure brand awareness. As with the interpretation of all research, it is important for readers to familiarise themselves with the methodologies used in order to clarify what exactly is being measured and how the data was collected.

Obviously, most marketers aim to build high levels of brand awareness within relevant market segments, giving rise to a continuing interest in developing the right metrics to measure brand effects. Metrics used to measure brand effects are collectively termed AAU metrics (Awareness, Attitudes and Usage).[35]

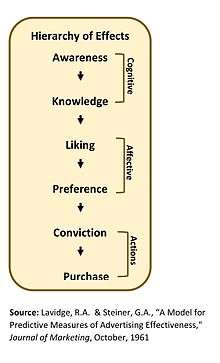

Brand awareness and the hierarchy of effects

Brand awareness is a standard feature of a group of models known as hierarchy of effects models. Hierarchical models are linear sequential models built on an assumption that consumers move through a series of cognitive and affective stages, beginning with brand awareness (or category awareness) and culminating in the purchase decision. [36] In these models, advertising and marketing communications operate as an external stimulus and the purchase decision is a consumer response.

A number of hierarchical models can be found in the literature including DAGMAR and AIDA.[37] In a survey of more than 250 papers, Vakratsas and Ambler (1999) found little empirical support for any of the hierarchies of effects.[38] In spite of that, some authors have argued that hierarchical models continue to dominate theory, especially in the area of marketing communications and advertising.[39]

The hierarchy of effects developed by Lavidge in the 1960s is one of the original hierarchical models. It proposes that customers progress through a sequence of six stages from brand awareness through to the purchase of a product.[40]

- Stage 1: Awareness - The consumer becomes aware of a category, product or brand (usually through advertising)

- ↓

- Stage 2: Knowledge - The consumer learns about the brand (e.g. sizes, colours, prices, availability etc)

- ↓

- Stage 3: Liking - The consumer develops a favourable/unfavourable disposition towards the brand

- ↓

- Stage 4: Preference - The consumer begins to rate one brand above other comparable brands

- ↓

- Stage 5: Conviction - The consumer demonstrates a desire to purchase (via inspection, sampling, trial)

- ↓

- Stage 6: Purchase - The consumer acquires the product

- Stage 1: Awareness - The consumer becomes aware of a category, product or brand (usually through advertising)

Hierarchical models have been widely adapted and many variations can be found, however, all follow the basic sequence which includes Cognition (C)- Affect (A) - Behaviour (B) and for this reason, they are sometimes known as C-A-B models.[41] Some of the more recent adaptations are designed to accommodate the consumer's digital media habits and opportunities for social influence.

Selected alternative hierarchical models follow:

- Modified AIDA model: Awareness→ Interest→ Conviction →Desire→ Action [44]

- AIDAS Model: Attention → Interest → Desire → Action → Satisfaction [45]

- AISDALSLove model: Awareness→ Interest→ Search →Desire→ Action → Like/dislike→ Share → Love/ Hate [46]

- Lavidge et al's Hierarchy of Effects: Awareness→ Knowledge→ Liking→ Preference→ Conviction→ Purchase[40]

- Rossiter and Percy's communications effects: Category Need → Brand Awareness → Brand Preference (Ab) → Purchase Intent→ Purchase Facilitation [48]

Marketing Implications of hierarchical models

It should be evident that brand awareness constitutes just one of six stages that outline the typical consumer's progress towards a purchase decision. While awareness is a necessary precondition for a purchase, awareness alone cannot guarantee the ultimate purchase. Consumers may be aware of a brand, but for different reasons, may not like it or may fail to develop a preference for that brand. Hence, brand awareness is an indicator of sales performance, but does not account for all sales performance.[49] For these reasons, marketers use a variety of metrics, including cognitive, affective and behavioral variables, to monitor a brand's market performance.

As consumers move through the hierarchy of effects (awareness→ knowledge→ liking→ preference→ conviction→ purchase), they rely on different sources of information to learn about brands. While main media advertising is useful for creating awareness, its capacity to convey long or complex messages is limited. In order to acquire more detailed knowledge about a brand, consumers rely on different sources such as product reviews, expert opinion, word-of-mouth referrals and brand/ corporate websites. As consumers move closer to the actual purchase, they begin to rely on more personal sources of information such as recommendations from friends and relatives or the advice of sales representatives.[50] For example, the opinion of an influential blogger might be enough to shore up preference/conviction while a salesperson might be necessary to close the actual purchase.

All hierarchical models indicate that brand awareness is a necessary precondition to brand attitude or brand liking, which serves to underscore the importance of creating high levels of awareness as early as possible in a product or brand life-cycle. Hierarchical models provide marketers and advertisers with basic insights about the nature of the target audience, the optimal message and media strategy indicated at different junctures throughout a product's life cycle. For new products, the main advertising objective should be to create awareness with a broad cross-section of the potential market. When the desired levels of awareness have been attained, the advertising effort should shift to stimulating interest, desire or conviction. The number of potential purchasers decreases as the product moves through the natural sales cycle in an effect likened to a funnel.[51] Later in the cycle, and as the number of prospects becomes smaller, the marketer can employ more tightly targeted promotions such as personal selling, direct mail and email directed at those individuals or sub-segments likely to exhibit a genuine interest in the product or brand.

Creating and maintaining brand awareness

Brand advertising can increase the probability that a consumer will include a given brand in his or her consideration set. Brand-related advertising expenditure has a positive affect on brand awareness levels. Virtually anything that exposes consumers to a brand increases brand awareness. “Repeat brand exposure in stores improves consumers' ability to recognize and recall the brand.”[52] Increased exposure to brand advertising can increase consumer awareness and facilitate consumer processing of the included information, and by doing this it can heighten consumers brand recall and attitude towards the brand.[53]

To increase the probability of a product's acceptance by the market, it is important to create high levels of brand awareness as early as practical in a product or brand's life-cycle. To achieve top-of-mind awareness, marketers have traditionally, relied on intensive advertising campaigns, especially at the time of a product launch.[54] To be successful, an intensive campaign utilises both broad reach (expose more people to the message) and high frequency (expose people multiple times to the message). Advertising, especially main media advertising, was seen as the most cost efficient means of reaching large audiences with the relatively high frequency needed to create high awareness levels. Nevertheless, intensive advertising campaigns can become very expensive and can rarely be sustained for long periods.

As new products enter the market growth stage, the number of competitors tends to increase with implications for market share. Marketers may need to maintain awareness at some predetermined level to ensure steady sales and stable market share. Marketers often rely on rough and ready 'rules-of-thumb' to estimate the amount of advertising expenditure required to achieve a given level of awareness. For instance, it was often held that to increase brand awareness by just one per cent, it was necessary to double the dollars spent on advertising.[55]

When a brand becomes established and attains the desired awareness levels (typically outlined in the marketing plan), the brand advertiser will shift from an intensive advertising campaign to a reminder campaign. The objective of a reminder campaign is simply to keep target audiences aware of the brand's existence and to introduce new life into the brand offer.[56] A reminder campaign typically maintains broad reach, but with reduced frequency and as a consequence is a less expensive advertising option. Reminder advertising is used by established brands, often when they are entering the maturity stage of the product lifecycle. In the decline stage, marketers often shift to a caretaker or maintenance program where advertising expenditure is cut back.

While advertising remains important for creating awareness, a number of changes in the media landscape and to consumer media habits have reduced the reliance on main media advertising. Instead, marketers are seeking to place their brand messages across a much wider variety of platforms. An increasing amount of consumer time and attention is devoted to digital communications devices - from computers and tablets through to cellphones. It is now possible to engage with consumers in a more cost efficient manner using platforms such as social media networks that command massive audiences. For example, Facebook has become an extremely important communications channel.[57] Moreover, social media channels allow for two-way, interactive communications that are not paralleled by traditional main media. Interactive communications provide more opportunities for brands to connect with audience members and to move beyond simple awareness, facilitating brand preference, brand conviction and ultimately brand loyalty.

The rise of social media networks has increased the opportunities for opinion leaders to play a role in brand awareness.[58] In theory, anyone can be an opinion leader e.g. celebrities, journalists or public figures, but the rise of the digital environment has changed our understanding of who is a potentially useful influencer. Indeed, the digital environment has created more opportunities for bloggers to become important influencers because they are seen as accessible, authentic and tend to have loyal followings.[59] Bloggers have become key influencers in important consumer goods and services including fashion, consumer electronics, food and beverage, cooking, restaurant dining and bars. For example, a recent survey by Collective Bias, showed that when it comes to product endorsements digital influencers are more popular than celebrities. Findings showed that only 3% of participants said they would consider buying a celebrity-endorsed item, in comparison to 60% who said they had been influenced by a blog review or social media post when shopping.[60] For marketers, the digital landscape has made it somewhat easier to identify social influencers.

Popular examples of brand advertising and promotion

The following examples illustrate how brand awareness and brand advertising are used in practice.

Coca-Cola 'Share a Coke' Campaign

.jpg)

Coca-Cola is a well-established brand with a long history and one that has achieved market dominance. For any brand, such as Coke, that controls some 70 percent of market share, there are relatively few opportunities to enlist new customers. Yet Coca-Cola is always on the lookout for novel communications that not only maintain its brand awareness, but that bring the brand to the attention of new audiences. The company launched a campaign which became known as ‘Share a Coke’, with the campaign objectives; "to strengthen the brand’s bond with Australia’s young adults – and inspire shared moments of happiness in the real and virtual worlds." [61] The campaign, originally launched in Australia became so successful that it was subsequently rolled out to other countries.

The concept was to introduce personalized Coke bottles or cans. Popular names were written in a 'look-alike Spencerian script' which is part of the Coke brand's distinctive brand identity. The campaign organisers seeded social media by targeting opinion leaders and influencers to get them to them lead the conversation and encourage others to seek out “Share a Coke” for themselves. [62] [63] Within days celebrities and others with no connection to Coke were spreading the concept across social networks. The campaign extended the audience reach as more people were exposed to the messages. According to Coke's creative team, "That [Australian] summer, Coke sold more than 250 million named bottles and cans in a nation of just under 23 million people". This campaign helped Coke extend its awareness across a broader age profile as they interacted with each customer on a personal level. [64]

Ronald McDonald and anthropomorphic brand characters

Consumers experience few difficuties assigning a personality to a brand and marketing communications often encourage consumers to think about brands as possessing human characteristics. [65] When brands are infused with human-like characteristics, it can assist in communicating a brand's values and creating distinctive brand identities that serve to differentiate an offering from competing brands. [66] “In an increasingly competitive marketplace, [some] companies rely on brand characters to create awareness, convey key product/service attributes or benefits, and attract consumers" (Keller, 2003).

The use of anthropomorphic characters has a long history. For example, the Michelin man, employed as a memorable character to sell Michelin car tyres, was introduced as early as 1894. These characters benefit the brand by creating memorable images in the consumer’s mind while conveying meanings that are consistent with the brand's values.

McDonald's created a similar “anthropomorphic brand character” known as Ronald Mcdonald as part of its brand identity. For younger consumers, Ronald McDonald injects a sense of fun and mystery into the McDonald's brand. For parents, the character clearly signals that McDonald's is a family friendly venue. Characters help to carry the brand's identity and can be seen as non-human 'spokes-character', contributing to a strong brand differentiation. The likeability of the brands character can “positively influence attitudes towards the brand and increase [consumers'] purchase intention” [67]

Mini

The well-known automotive manufacturer, Mini, investigated its brand perception in the UK by carrying out 55 in-depth interview designed to elicit key feedback about the brand's values. Consumers felt that the symbolic elements which represented the brand were that it was “fun, stylish and sporty image”.[68]

Customer engagement with the MINI brand on a Facebook fan-page, promoted “positive effects on consumers’ brand awareness, through WOM activities and the purchase intention was achieved”.[69] The brand, therefore, connected with users at an emotional level.[68]

See also

- Advertising management - creating brand awareness is the primary function of advertising

- Attitude-toward-the-ad models

- Brand - creating and maintaining high levels of brand awareness is one of the primary functions of brand management

- Consumer behaviour - detailed overview of how consumers move from awareness through to the actual purchase

- Marketing management

- Product life-cycle management (marketing) - explains how levels of brand awareness change over a product's life cycle

- Purchase funnel - explains how brand awareness changes as different segments of the market begin to adopt a product or brand

References

- ↑ Business Dictionary Online, http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/brand-awareness.html

- ↑ Pham, M. T. and Higgins, E.T., "Promotion and Prevention in Consumer Decision Making: The State of the Art and Theoretical Propositions," in S. Ratneshwar and David Glen Mick, (eds), Inside Consumption: Consumer Motives, Goals, and Desires, , London: Routledge, 2005, pp 8-43.

- 1 2 Keller, Kevin (1993). "Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity". The Journal of Marketing. 1 (22).

- ↑ Ya-Hsin, H., Ya-hei, H., Suh-Yueh, C., & Wenchang, F. (2014). Is Brand Awareness a Marketing Placebo?. International Journal Of Business & Information, 9(1), 29-60.

- ↑ Aaker, D.A. (1991), Managing Brand Equity: Capitalizing on the Value of a Brand Name, N.Y. The Free Press

- 1 2 Aaker, D. A. (1991a). Are brand equity investments really worthwhile?. Admap, 14-17.

- ↑ Interbrand,http://interbrand.com/best-brands/best-global-brands/2016/ranking

- ↑ Belch, G. E., & Belch, M. A., Advertising and Promotion: An integrated marketing communications perspective,9th ed., New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Irwin, 2012

- ↑ Trout, J. and Ries, A., "The Positioning Era Cometh", Advertising Age [Special Feature on Positioning], 24 April 1972

- ↑ Reilly, M. and Parkinson, T.L., "Individual and Product Correlates of Evoked Set Size For Consumer Package Goods", in Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 12, Elizabeth C. Hirschman and Moris B. Holbrook (eds), Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research, pp 492-497, Online: http://acrwebsite.org/volumes/6440/volumes/v12/NA-12

- ↑ Percy, Larry; Rossiter, John (1992). "A model of brand awareness and brand attitude advertising strategies". Psychology & Marketing. 9 (4): 263–274. doi:10.1002/mar.4220090402.

- ↑ Solomon, M., Hughes, A., Chitty, B., Marshall, G. and Stuart, E., Marketing: Real People, Real Choices,pp 17-19

- ↑ Farris, Paul W.; Neil T. Bendle; Phillip E. Pfeifer; David J. Reibstein (2010). Marketing Metrics: The Definitive Guide to Measuring Marketing Performance. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education,

- ↑ See, for instance, Koniewski, M., "Brand Awareness and Brand Loyalty", PMR Research Paper, Feb, 2012, www.research-pmr.com

- ↑ Manternach, L. (2011). Does your brand have top of mind awareness?. Corridor Business Journal, 7(52), 26.

- ↑ Driesener, C., Paech, S., Romaniuk, J., & Sharp, B., "Brand and Advertising Awareness: A Replication and extension of a known empirical generalization," Australasian Marketing Journal, vol. 12, no. 3, 2004, pp 70-80

- ↑ Howard, J. A., & Sheth, J.N. (1969). The Theory of Buyer Behaviour. Wiley, N.Y.

- ↑ Meenaghan, R., "The role of advertising in brand image development", Journal of Product and Brand Management, Vol. 4, no. 4, 1995, pp.23 - 34

- ↑ Chon, K.Y., Pizam, A. and Mansfeld, Y., Consumer Behavior in Travel and Tourism, 2nd ed, 2000, New York, Haworth, pp 86-87

- ↑ Roberts, J., "A Grounded Model of Consideration Set Size and Composition", in Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 16, Thomas K. Srull, (ed.) Provo, UT, Association for Consumer Research, 1989, pp 749-757, Online: http://acrwebsite.org/volumes/5967/volumes/v16/NA-16

- ↑ Hatten, R.S., Small Business Management: Entrepreneurship and Beyond, Mason, OH, South-Western Cengage, 2012, p.317

- ↑ Solomon, M., Hughes, A., Chitty, B., Marshall, G. and Stuart, E., Marketing: Real People, Real Choices,pp 363-364

- ↑ ACCC, The Comparator Website Industry in Australia, Commonwealth of Australia, 2014, p. 8

- ↑ Percy, L. and Rossiter, J., "A Model of Brand Awareness and Brand Attitude Advertising Strategies", Psychology and Marketing, Vol. 7, no. 4, 1992, pp 263-274

- ↑ Rossiter, J and Bellman, S., Marketing Communications: Theory and Applications, Pearson Australia, 2005, pp 157-160

- ↑ Rossiter, J. R., Percy, L. and Donovan, R.J., “A Better Advertising Planning Grid,” Journal of Advertising Research, vol. 31 (October/November), 1991, pp 11-21.

- 1 2 Aaker, D. (1996). Building Strong Brands. New York: Free Press Publications.

- ↑ Merriam-Webster Dictionary, http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/household%20name

- ↑ Business Dictionary,http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/generic-brand.html

- ↑ Hsia, H.J., Mass Communications Research Methods: A Step-by-Step Approach," Routledge"

- ↑ Sutherland, M. and Sylvester, A.K., Advertising and the Mind of the Consumer: What Works, What Doesn't and Why, Great Britain, Kogan Page, 2000 pp 198-199

- ↑ Interbrand, http://interbrand.com/best-brands/

- ↑ Millward-Brown, http://www.millwardbrown.com/brandz/top-global-brands

- ↑ Campaign Asia, http://www.campaignasia.com/Top1000Brands

- ↑ Farris, Paul W.; Neil T. Bendle; Phillip E. Pfeifer; David J. Reibstein (2010). Marketing Metrics: The Definitive Guide to Measuring Marketing Performance. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc. ISBN 0137058292. The Marketing Accountability Standards Board (MASB) endorses the definitions, purposes, and constructs of classes of measures that appear in Marketing Metrics as part of its ongoing Common Language in Marketing Project.

- ↑ Egan, J., Marketing Communications, London, Thomson Learning, pp 42-43

- ↑ Diehl, D. and Terlutter, R., "The Role of Lifestyle and Personality in Explaining Attitude to the Ad," in Branding and Advertising, Flemming Hansen, Lars Bech Christensen (eds), p. 307

- ↑ Demetrios Vakratsas and Tim Ambler, "How Advertising Works: What Do We Really Know?" Journal of Marketing, Vol. 63, No. 1, 1999, pp. 26-43 DOI: 10.2307/1251999 URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1251999

- ↑ O’Shaughnessy, J., Explaining Buyer Behavior, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1992

- 1 2 Lavidge,R.J. and Steiner, G.A., "A Model for Predictive Measures of Advertising Effectiveness," Journal of Marketing, October, 1961, pp 59-62

- ↑ Barry, T.E., "The Development of the Hierarchy of Effects: An Historical Perspective," Current Issues & Research in Advertising vol. 10, no. 2, 1987, pp. 251–295

- ↑ Priyanka, R., "AIDA Marketing Communication Model: Stimulating a purchase decision in the minds of the consumers through a linear progression of steps," International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research in Social Management, Vol. 1 , 2013, pp 37-44.

- ↑ E. St Elmo Lewis, Financial Advertising. (The History of Advertising), USA, Levey Brothers, 1908

- ↑ Barry, T.E. and Howard, D.J., "A Review and Critique of the Hierarchy of Effects in Advertising," International Journal of Advertising, vol 9, no.2, 1990, pp. 121–135

- ↑ Barry, T.E. and Howard, D.J., "A Review and Critique of the Hierarchy of Effects in Advertising," International Journal of Advertising, Vol. 9, no. 2, 1990, pp 121-135

- ↑ Wijaya, Bambang Sukma (2012). “The Development of Hierarchy of Effects Model in Advertising”, International Research Journal of Business Studies, 5 (1), April–July 2012, p. 73-85

- ↑ Dutka, S., Defining Advertising Goals for Measured Advertising, NTC Business Books, 1995

- ↑ Rossiter, J.R. and Percy, L.,"Advertising Communication Models", in: Advances in Consumer Research, Volume 12, Elizabeth C. Hirschman and Moris B. Holbrook (eds), Provo, UT : Association for Consumer Research, 1985, pp 510-524., Online: http://acrwebsite.org/volumes/6443/volumes/v12/NA-12 or http://www.acrwebsite.org/search/view-conference-proceedings.aspx?Id=6443

- ↑ Rossiter, J and Bellman, S., Marketing Communications: Theory and Applications, Pearson Australia, 2005, p. 107-109

- ↑ Srinivasan,N., "Pre-purchase External Search Information," in Valarie A. Zeithaml (ed), Review of Marketing 1990, Marketing Classics Press (AMA), 2011, pp 153-189

- ↑ Court, D. Elzinga, D., Mulder, S. and Vetvik, O.J., "The Consumer Decision Journey", McKinsey Quarterly, June 2009, Online: http://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/marketing-and-sales/our-insights/the-consumer-decision-journey

- ↑ Huang, R., & Sarigöllü, E. (2012). How brand awareness relates to market outcome, brand equity, and the marketing mix. Journal Of Business Research, 6592-99.

- ↑ Schmidt, S., & Eisend, M. (2015). Advertising Repetition: A Meta-Analysis on Effective Frequency in Advertising. Journal Of Advertising, 44(4), 415-428.

- ↑ Belch, G, Belch, M.A, Kerr, G. and Powell, I., Advertising and Promotion Management: An Integrated Marketing Communication Perspective, McGraw-Hill, Sydney, Australia, 2009, p.126

- ↑ See for instance, Jones, J.P, The Ultimate Secrets of Advertising, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, 2002

- ↑ Business Dictionary (online), http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/reminder-advertising.html

- ↑ Dokyun, L., Hosanagar, K., & Nair, H. S. (2015). Advertising Content and Consumer Engagement on Social Media: Evidence from Facebook. Working Papers (Faculty) -- Stanford Graduate School Of Business, 1-41.

- ↑ Malaska, M., Saraniemi, S., & Tahtinen, J. (2010, September). Co-creation of Branding by Network Actors. Paper presented at 10th Annual EBRF Conference: Co-Creation as a Way Forward, (pp. 15-17), Nokia, Finland.

- ↑ Paul McIntyre, “Independent bloggers overtake celebrities as key social media influencers”, Australian Financial Review , 22 June 2015 Online:http://www.afr.com/business/independent-bloggers-overtake-celebrities-as-key-social-media-influencers-20150528-ghbovu

- ↑ Singh, N., "Celebrity Vs Shopper" Harper's Bazaar (Australia), 2 April 2016 Online: http://www.harpersbazaar.com.au/news/fashion-buzz/2016/4/bloggers-are-more-popular-than-celebrities/

- ↑ Coca-Cola company. "Share a Coke: How the Groundbreaking Campaign Got Its Start ‘Down Under’", Retrieved from http://www.coca-colacompany.com/stories/share-a-coke-how-the-groundbreaking-campaign-got-its-start-down-under/

- ↑ Coca Cola, Share a Coke, [Brand campaign website],https://www.shareacoke.com

- ↑ Ogilvy, Share a Coke Campaign Brief and Creative Concept, [Advertising agency], http://ogilvy.com.au/our-work/share-coke

- ↑ Coca-Cola company. "Share a Coke: How the Groundbreaking Campaign Got Its Start ‘Down Under’", Retrieved from http://www.coca-colacompany.com/stories/share-a-coke-how-the-groundbreaking-campaign-got-its-start-down-under/

- ↑ Puzakova, M., Kwak,H. and Rocereto, J., "Pushing the Envelope of Brand and Personality: Antecedents and Moderators of Anthropomorphized Brands", in Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 36, Ann L. McGill and Sharon Shavitt, Duluth (eds), MN: Association for Consumer Research, 2007, pp 413-420.[url]: http://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/14399/volumes/v36/NA-36

- ↑ Smith, A. C., Graetz, B. R. and Westerbeek, H. M., "Brand personality in a membership‐based organisation", International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, Vol. 11 No. 3, 2006, pp. 251-266.

- ↑ Hosany, S., Prayag, G., Martin, D., & Lee, W., "Theory and Strategies of Anthropomorphic Brand Characters from Peter Rabbit, Mickey Mouse, and Ronald McDonald, to Hello Kitty. Journal of Marketing Management, vol. 29, no 1/2, 2013, pp 48-68

- 1 2 Simms, C. D., & Trott, P. (2006). "The perceptions of the BMW Mini brand: the importance of historical associations and the development of a model," Journal of Product & Brand Management, 228-238.

- ↑ Hutter, K., Hautz, J., Dennhardt, S., & Fuller, J. (2013), "The impact of user interactions in social media on brand awareness and purchase intention: the case of MINI on Facebook," Journal of Product & Brand Management, 342-351.