Choroid plexus

| Choroid plexus | |

|---|---|

Scheme of roof of fourth ventricle. The arrow is in the median aperture. 1: Inferior medullary velum 2: Choroid plexus 3: Cisterna magna of subarachnoid space 4: Central canal 5: Corpora quadrigemina 6: Cerebral peduncle 7: Superior medullary velum 8: Ependymal lining of ventricle 9: Pontine cistern of subarachnoid space | |

| |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Plexus choroideus |

| MeSH | D002831 |

| NeuroNames | 1377 |

| TA |

A14.1.09.279 A14.1.01.307 A14.1.01.306 A14.1.01.304 A14.1.05.715 |

| FMA | 61934 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The choroid plexus is a plexus of cells that produces the cerebrospinal fluid in the ventricles of the brain. The choroid plexus consists of modified ependymal cells.

Structure

Location

There are four choroid plexuses in the brain, one in each of the ventricles. Choroid plexus is present in all parts of the ventricular system except for the cerebral aqueduct, the frontal horn and the occipital horn of the lateral ventricles.[1]

Choroid plexus is located in the inferior horn of the lateral ventricle, and passes into the interventricular foramen to the third ventricle. There is choroid plexus in the fourth ventricle beneath the cerebellum.

Microanatomy

The choroid plexus consists of a layer of cuboidal epithelial cells surrounding a core of capillaries and loose connective tissue. The epithelium of the choroid plexus is continuous with the ependymal cell layer that lines the ventricles. The cells of the choroid plexus are non ciliated[2] but, unlike the ependyma, the choroid plexus epithelial layer has tight junctions[3] between the cells on the side facing the ventricle (apical surface). These tight junctions prevent the majority of substances from crossing the cell layer into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF); thus the choroid plexus acts as a blood–CSF barrier. The choroid plexus folds into many villi around each capillary, creating frond-like processes that project into the ventricles. The villi, along with a brush border of microvilli, greatly increases the surface area of the choroid plexus. CSF is formed as plasma is filtered from the blood through the epithelial cells. Choroid plexus epithelial cells actively transport sodium ions into the ventricles and water follows the resulting osmotic gradient.[4]

The choroid plexus consists of many capillaries, separated from the ventricles by choroid epithelial cells. Fluid filters through these cells from blood to become cerebrospinal fluid. There is also much active transport of substances into, and out of, the CSF as it is made.

Function

The choroid plexus mediates the production of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). CSF acts as a medium for filtration system that facilitates the removal of metabolic waste from the brain and exchange of biomolecules and xenobiotics into and out of the brain.[5][6][7] In this way the choroid plexus has a very important role in helping to maintain the delicate extracellular environment required by the brain to function optimally.

The choroid plexus is also a major source of transferrin secretion that plays a part in iron homeostasis in the brain.[8][9]

Blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier

The blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier (BCSFB) is a fluid–brain barrier that is composed of a pair of membranes that separate blood from CSF and CSF from brain tissue.[10] The blood–CSF boundary at the choroid plexus is a membrane composed of epithelial cells and tight junctions that link them.[10] The brain–CSF boundary is the arachnoid membrane, which envelops the surface of the brain.[10]

Similar to the blood–brain barrier, the blood–CSF barrier functions to prevent the passage of most blood-borne substances into the brain, while selectively permitting the passage specific substances into the brain and facilitating the removal of brain metabolites and metabolic waste into the blood.[10][11][12][7] Despite the similar function between the BBB and BCSFB, each facilitates the transport of different substances into the brain due to the distinct structural characteristics between the two barrier systems.[10][11] For a number of substances, the BCSFB is the primary site of entry into brain tissue.[10]

The blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier has also been shown to modulate the entry of leukocytes from the blood to the central nervous system. The choroid plexus cells secrete cytokines that recruit monocyte-derived macrophages, among other cells, to the brain. This cellular trafficking has implications both in normal brain homeostasis as in neuroinflammatory processes.[13]

Clinical significance

Choroid plexus cysts

During embryological development, some fetuses may form choroid plexus cysts. These fluid-filled cysts can be detected by a detailed second trimester ultrasound. The finding is relatively common, with a prevalence of ~1%. Choroid plexus cysts are usually an isolated finding.[14] The cysts typically disappear later during pregnancy, and are usually harmless. They have no effect on infant and early childhood development.[15]

Cysts confers a 1% risk of fetal aneuploidy.[16] The risk of aneuploidy increases to 10.5-12% if other risk factors or ultrasound findings are noted. Size, location, disappearance or progression, and whether the cysts are found on both sides or not do not affect the risk of aneuploidy. 44-50% of Edwards syndrome (trisomy 18) cases will present with choroid plexus cysts, as well 1.4% of Down syndrome (trisomy 21) cases. ~75% of abnormal karyotypes associated with choroid plexus systs are trisomy 18, while the remainder are trisomy 21.[14]

Other

There are three graded types of choroid plexus tumor that mainly affect young children. These malignant neoplasms are rare.

Etymology

Choroid plexus translates from the Latin plexus chorioides,[17] which mirrors Ancient Greek χοριοειδές πλέγμα.[18] The word chorion was used by Galen to refer to the outer membrane enclosing the fetus. Both meanings of the word plexus are given as pleating, or braiding.[18] As often happens language changes and the use of both choroid or chorioid is both accepted. Nomina Anatomica (now Terminologia Anatomica) reflected this dual usage.

Additional images

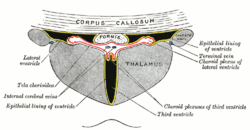

Coronal section of inferior horn of lateral ventricle.

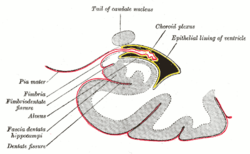

Coronal section of inferior horn of lateral ventricle. Choroid Plexus Histology 40x

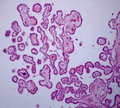

Choroid Plexus Histology 40x- Choroid plexus

- Choroid plexus

See also

References

- ↑ Young PA (2007). Basic clinical neuroscience (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-7817-5319-7.

- ↑ van Leeuwen LM, Evans RJ, Jim KK, Verboom T, Fang X, Bojarczuk A, Malicki J, Johnston SA, van der Sar AM (February 2018). "A transgenic zebrafish model for the in vivo study of the blood and choroid plexus brain barriers using claudin 5". Biology Open. 7 (2): bio030494. doi:10.1242/bio.030494. PMC 5861362. PMID 29437557.

- ↑ Hall, John (2011). Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology (12th ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 749. ISBN 978-1-4160-4574-8.

- ↑ Guyton AC, Hall JE (2005). Textbook of medical physiology (11th ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. pp. 764–7. ISBN 978-0-7216-0240-0.

- ↑ Plog BA, Nedergaard M (January 2018). "The Glymphatic System in Central Nervous System Health and Disease: Past, Present, and Future". Annual Review of Pathology. 13: 379–394. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-051217-111018. PMC 5803388. PMID 29195051.

- ↑ Abbott NJ, Pizzo ME, Preston JE, Janigro D, Thorne RG (March 2018). "The role of brain barriers in fluid movement in the CNS: is there a 'glymphatic' system?". Acta Neuropathologica. 135 (3): 387–407. doi:10.1007/s00401-018-1812-4. PMID 29428972.

- 1 2 Marszałek M (May 2017). "Alzheimer's disease against peptides products of enzymatic cleavage APP protein: Biological, pathobiological and physico-chemical properties of fibrillating peptides". Postepy Higieny I Medycyny Doswiadczalnej (Online). 71: 398–410. PMID 28513463.

In addition, the following studies concerning AD patients might prove challenging and simultaneously promising: peptides translocation through Blood-Brain - Barrier (BBB) and Blood-Cerebrospinal Fluid Barrier (BCSFB) and their removal from the brain according to a new concept of glymphatic system

- ↑ Moos, T (November 2002). "Brain iron homeostasis". Danish Medical Bulletin. 49 (4): 279–301. PMID 12553165.

- ↑ Moos, T; Rosengren Nielsen, T; Skjørringe, T; Morgan, EH (December 2007). "Iron trafficking inside the brain". Journal of Neurochemistry. 103 (5): 1730–40. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04976.x. PMID 17953660.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Laterra J, Keep R, Betz LA, et al. (1999). "Blood–Cerebrospinal Fluid Barrier". Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven.

- 1 2 Ueno M (March 2017). "Elucidation of mechanism of blood-brain barrier damage for prevention and treatment of vascular dementia". Rinsho Shinkeigaku = Clinical Neurology (in Japanese). 57 (3): 95–109. doi:10.5692/clinicalneurol.cn-001004. PMID 28228623.

It is well-known that the blood-brain barrier (BBB) plays significant roles in transporting intravascular substances into the brain. ... However, the substances cannot invade the ventricles easily as there are tight junctions between epithelial cells in the choroid plexus. This restricted movement of the substances across the cytoplasm of the epithelial cells constitutes a blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier (BCSFB). In the brain, there are circumventricular organs, in which the barrier function is imperfect in capillaries. Accordingly, it is reasonable to consider that intravascular substances can move in and around the parenchyma of the organs. Actually, it was reported in mice that intravascular substances moved in the corpus callosum, medial portions of the hippocampus, and periventricular areas via the subfornical organs or the choroid plexus. Regarding pathways of intracerebral interstitial and cerebrospinal fluids to the outside of the brain, two representative drainage pathways, or perivascular drainage and glymphatic pathways, are being established

- ↑ Ueno M, Chiba Y, Murakami R, Matsumoto K, Kawauchi M, Fujihara R (April 2016). "Blood-brain barrier and blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier in normal and pathological conditions". Brain Tumor Pathology. 33 (2): 89–96. doi:10.1007/s10014-016-0255-7. PMID 26920424.

Blood-borne substances can invade into the extracellular spaces of the brain via endothelial cells in sites without the blood-brain barrier (BBB), and can travel through the interstitial fluid (ISF) of the brain parenchyma adjacent to non-BBB sites. It has been shown that cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drains directly into the blood via the arachnoid villi and also into lymph nodes via the subarachnoid spaces of the brain, while ISF drains into the cervical lymph nodes through perivascular drainage pathways. In addition, the glymphatic pathway of fluids, characterized by para-arterial pathways, aquaporin4-dependent passage through astroglial cytoplasm, interstitial spaces, and paravenous routes, has been established.

- ↑ Schwartz M, Baruch K (January 2014). "The resolution of neuroinflammation in neurodegeneration: leukocyte recruitment via the choroid plexus". The EMBO Journal. 33 (1): 7–22. doi:10.1002/embj.201386609. PMC 3990679. PMID 24357543.

- 1 2 Drugan A, Johnson MP, Evans MI (January 2000). "Ultrasound screening for fetal chromosome anomalies". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 90 (2): 98–107. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(20000117)90:2<98::AID-AJMG2>3.0.CO;2-H. PMID 10607945.

- ↑ Digiovanni LM, Quinlan MP, Verp MS (August 1997). "Choroid plexus cysts: infant and early childhood developmental outcome". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 90 (2): 191–4. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00251-2. PMID 9241291.

- ↑ Peleg D, Yankowitz J (July 1998). "Choroid plexus cysts and aneuploidy". Journal of Medical Genetics. 35 (7): 554–7. PMC 1051365. PMID 9678699.

- ↑ Suzuki, S., Katsumata, T., Ura, R. Fujita, T., Niizima, M. & Suzuki, H. (1936). Über die Nomina Anatomica Nova. Folia Anatomica Japonica, 14, 507-536.

- 1 2 Liddell HG, Scott R (1940). A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Sources

- Brodbelt A, Stoodley M (October 2007). "CSF pathways: a review". British Journal of Neurosurgery. 21 (5): 510–20. doi:10.1080/02688690701447420. PMID 17922324.

- Strazielle N, Ghersi-Egea JF (July 2000). "Choroid plexus in the central nervous system: biology and physiopathology". Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 59 (7): 561–74. PMID 10901227.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Choroid plexus. |

- 3-Dimensional images of choroid plexus (marked red)

- "Anatomy diagram: 13048.000-3". Roche Lexicon - illustrated navigator. Elsevier. Archived from the original on 2014-01-01.

- MedPix Images of Choroid Plexus

- More info at BrainInfo