Bionics

Bionics or biologically inspired engineering is the application of biological methods and systems found in nature to the study and design of engineering systems and modern technology.[1]

The word bionic was coined by Jack E. Steele in 1958, possibly originating from the technical term bion (pronounced BEE-on; from Ancient Greek: βίος bíos), meaning 'unit of life' and the suffix -ic, meaning 'like' or 'in the manner of', hence 'like life'. Some dictionaries, however, explain the word as being formed as a portmanteau from biology and electronics.[2] It was popularized by the 1970s U.S. television series The Six Million Dollar Man and The Bionic Woman, both based upon the novel Cyborg by Martin Caidin, which was itself influenced by Steele's work. All feature humans given superhuman powers by electromechanical implants.

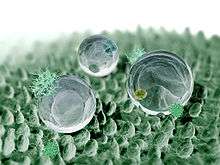

The transfer of technology between lifeforms and manufactured objects is, according to proponents of bionic technology, desirable because evolutionary pressure typically forces living organisms, including fauna and flora, to become highly optimized and efficient. A classical example is the development of dirt- and water-repellent paint (coating) from the observation that practically nothing sticks to the surface of the lotus flower plant (the lotus effect)..

The term "biomimetic" is preferred when reference is made to chemical reactions. In that domain, biomimetic chemistry refers to reactions that, in nature, involve biological macromolecules (e.g. enzymes or nucleic acids) whose chemistry can be replicated in vitro using much smaller molecules.

Examples of bionics in engineering include the hulls of boats imitating the thick skin of dolphins; sonar, radar, and medical ultrasound imaging imitating animal echolocation.

In the field of computer science, the study of bionics has produced artificial neurons, artificial neural networks,[3] and swarm intelligence. Evolutionary computation was also motivated by bionics ideas but it took the idea further by simulating evolution in silico and producing well-optimized solutions that had never appeared in nature.

It is estimated by Julian Vincent, professor of biomimetics at the University of Bath's Department of Mechanical Engineering, that "at present there is only a 12% overlap between biology and technology in terms of the mechanisms used".[4]

History

The name biomimetics was coined by Otto Schmitt in the 1950s. The term bionics was coined by Jack E. Steele in 1958 while working at the Aeronautics Division House at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. However, terms like biomimicry or biomimetics are more preferred in the technology world in efforts to avoid confusion between the medical term bionics. Coincidentally, Martin Caidin used the word for his 1972 novel Cyborg, which inspired the series The Six Million Dollar Man. Caidin was a long-time aviation industry writer before turning to fiction full-time.

Methods

The study of bionics often emphasizes implementing a function found in nature rather than imitating biological structures. For example, in computer science, cybernetics tries to model the feedback and control mechanisms that are inherent in intelligent behavior, while artificial intelligence tries to model the intelligent function regardless of the particular way it can be achieved.

The conscious copying of examples and mechanisms from natural organisms and ecologies is a form of applied case-based reasoning, treating nature itself as a database of solutions that already work. Proponents argue that the selective pressure placed on all natural life forms minimizes and removes failures.

Although almost all engineering could be said to be a form of biomimicry, the modern origins of this field are usually attributed to Buckminster Fuller and its later codification as a house or field of study to Janine Benyus.

There are generally three biological levels in the fauna or flora, after which technology can be modeled:

- Mimicking natural methods of manufacture

- Imitating mechanisms found in nature (velcro)

- Studying organizational principles from the social behaviour of organisms, such as the flocking behaviour of birds, optimization of ant foraging and bee foraging, and the swarm intelligence (SI)-based behaviour of a school of fish.

Examples

- In robotics, bionics and biomimetics are used to apply the way animals move to the design of robots. BionicKangaroo was based on the movements and physiology of kangaroos.

- Velcro is the most famous example of biomimetics. In 1948, the Swiss engineer George de Mestral was cleaning his dog of burrs picked up on a walk when he realized how the hooks of the burrs clung to the fur.

- The horn-shaped, saw-tooth design for lumberjack blades used at the turn of the 19th century to cut down trees when it was still done by hand was modeled after observations of a wood-burrowing beetle. It revolutionized the industry because the blades worked so much faster at felling trees.

- Cat's eye reflectors were invented by Percy Shaw in 1935 after studying the mechanism of cat eyes. He had found that cats had a system of reflecting cells, known as tapetum lucidum, which was capable of reflecting the tiniest bit of light.

- Leonardo da Vinci's flying machines and ships are early examples of drawing from nature in engineering.

- Resilin is a replacement for rubber that has been created by studying the material also found in arthropods.

- Julian Vincent drew from the study of pinecones when he developed in 2004 "smart" clothing that adapts to changing temperatures. "I wanted a nonliving system which would respond to changes in moisture by changing shape", he said. "There are several such systems in plants, but most are very small — the pinecone is the largest and therefore the easiest to work on". Pinecones respond to higher humidity by opening their scales (to disperse their seeds). The "smart" fabric does the same thing, opening up when the wearer is warm and sweating, and shutting tight when cold.

- "Morphing aircraft wings" that change shape according to the speed and duration of flight were designed in 2004 by biomimetic scientists from Penn State University. The morphing wings were inspired by different bird species that have differently shaped wings according to the speed at which they fly. In order to change the shape and underlying structure of the aircraft wings, the researchers needed to make the overlying skin also be able to change, which their design does by covering the wings with fish-inspired scales that could slide over each other. In some respects this is a refinement of the swing-wing design.

- Some paints and roof tiles have been engineered to be self-cleaning by copying the mechanism from the Nelumbo lotus.[5]

- Cholesteric liquid crystals (CLCs) are the thin-film material often used to fabricate fish tank thermometers or mood rings, that change color with temperature changes. They change color because their molecules are arranged in a helical or chiral arrangement and with temperature the pitch of that helical structure changes, reflecting different wavelengths of light. Chiral Photonics, Inc. has abstracted the self-assembled structure of the organic CLCs to produce analogous optical devices using tiny lengths of inorganic, twisted glass fiber.

- Nanostructures and physical mechanisms that produce the shining color of butterfly wings were reproduced in silico by Greg Parker, professor of Electronics and Computer Science at the University of Southampton and research student Luca Plattner in the field of photonics, which is electronics using photons as the information carrier instead of electrons.

- The wing structure of the blue morpho butterfly was studied and the way it reflects light was mimicked to create an RFID tag that can be read through water and on metal.[6]

- The wing structure of butterflies has also inspired the creation of new nanosensors to detect explosives.[7]

- Neuromorphic chips, silicon retinae or cochleae, has wiring that is modelled after real neural networks. S.a.: connectivity.

- Technoecosystems or 'EcoCyborg' systems involve the coupling of natural ecological processes to technological ones which mimic ecological functions. This results in the creation of a self-regulating hybrid system.[8] Research into this field was initiated by Howard T. Odum,[9] who perceived the structure and emergy dynamics of ecosystems as being analogous to energy flow between components of an electrical circuit.

- Medical adhesives involving glue and tiny nano-hairs are being developed based on the physical structures found in the feet of geckos.

- Computer viruses also show similarities with biological viruses in their way to curb program-oriented information towards self-reproduction and dissemination.

- The cooling system of the Eastgate Centre building in Harare was modeled after a termite mound to achieve very efficient passive cooling.

- Adhesive which allows mussels to stick to rocks, piers and boat hulls inspired bioadhesive gel for blood vessels.[10]

- Through the field of bionics, new aircraft designs with far greater agility and other advantages may be created. This has been described by Geoff Spedding and Anders Hedenström in an article in Journal of Experimental Biology. Similar statements were also made by John Videler and Eize Stamhuis in their book Avian Flight [11] and in the article they present in Science about LEVs.[12] John Videler and Eize Stamhuis have since worked out real-life improvements to airplane wings, using bionics research. This research in bionics may also be used to create more efficient helicopters or miniature UAVs. This latter was stated by Bret Tobalske in an article in Science about Hummingbirds.[13] Bret Tobalske has thus now started work on creating these miniature UAVs which may be used for espionage. UC Berkeley as well as ESA have finally also been working in a similar direction and created the Robofly [14] (a miniature UAV) and the Entomopter (a UAV which can walk, crawl and fly).[15]

Specific uses of the term

In medicine

Bionics refers to the flow of concepts from biology to engineering and vice versa. Hence, there are two slightly different points of view regarding the meaning of the word.

In medicine, bionics means the replacement or enhancement of organs or other body parts by mechanical versions. Bionic implants differ from mere prostheses by mimicking the original function very closely, or even surpassing it.

Bionics' German equivalent, Bionik, always adheres to the broader meaning, in that it tries to develop engineering solutions from biological models. This approach is motivated by the fact that biological solutions will usually be optimized by evolutionary forces.

While the technologies that make bionic implants possible are developing gradually, a few successful bionic devices exist, a well known one being the Australian-invented multi-channel cochlear implant (bionic ear), a device for deaf people. Since the bionic ear, many bionic devices have emerged and work is progressing on bionics solutions for other sensory disorders (e.g. vision and balance). Bionic research has recently provided treatments for medical problems such as neurological and psychiatric conditions, for example Parkinson's disease and epilepsy.[16]

By 2004 fully functional artificial hearts were developed. Significant progress is expected with the advent of nanotechnology. A well-known example of a proposed nanodevice is a respirocyte, an artificial red cell, designed (though not built yet) by Robert Freitas.

Kwabena Boahen from Ghana was a professor in the Department of Bioengineering at the University of Pennsylvania. During his eight years at Penn, he developed a silicon retina that was able to process images in the same manner as a living retina. He confirmed the results by comparing the electrical signals from his silicon retina to the electrical signals produced by a salamander eye while the two retinas were looking at the same image.

In 2007 the Scottish company Touch Bionics launched the first commercially available bionic hand, named "i-Limb Hand". According to the firm, by May 2010 it has been fitted to more than 1,200 patients worldwide.[17]

The Nichi-In group is working on biomimicking scaffolds in tissue engineering, stem cells and regenerative medicine have given a detailed classification on biomimetics in medicine.[18]

On 21 July 2015, the BBC’s medical correspondent Fergus Walsh reported, "Surgeons in Manchester have performed the first bionic eye implant in a patient with the most common cause of sight loss in the developed world. Ray Flynn, 80, has dry age-related macular degeneration which has led to the total loss of his central vision. He is using a retinal implant which converts video images from a miniature video camera worn on his glasses. He can now make out the direction of white lines on a computer screen using the retinal implant." The implant, known as the Argus II and manufactured in the US by the company Second Sight Medical Products, had been used previously in patients who were blind as the result of the rare inherited degenerative eye disease retinitis pigmentosa.[19]

Politics

A political form of biomimicry is bioregional democracy, wherein political borders conform to natural ecoregions rather than human cultures or the outcomes of prior conflicts.

Critics of these approaches often argue that ecological selection itself is a poor model of minimizing manufacturing complexity or conflict, and that the free market relies on conscious cooperation, agreement, and standards as much as on efficiency – more analogous to sexual selection. Charles Darwin himself contended that both were balanced in natural selection – although his contemporaries often avoided frank talk about sex, or any suggestion that free market success was based on persuasion, not value.

Advocates, especially in the anti-globalization movement, argue that the mating-like processes of standardization, financing and marketing, are already examples of runaway evolution – rendering a system that appeals to the consumer but which is inefficient at use of energy and raw materials. Biomimicry, they argue, is an effective strategy to restore basic efficiency.

Biomimicry is also the second principle of Natural Capitalism.

Other uses

Business biomimetics is the latest development in the application of biomimetics. Specifically it applies principles and practice from biological systems to business strategy, process, organisation design and strategic thinking. It has been successfully used by a range of industries in FMCG, defence, central government, packaging and business services. Based on the work by Phil Richardson at the University of Bath[20] the approach was launched at the House of Lords in May 2009.

In a more specific meaning, it is a creativity technique that tries to use biological prototypes to get ideas for engineering solutions. This approach is motivated by the fact that biological organisms and their organs have been well optimized by evolution. In chemistry, a biomimetic synthesis is a chemical synthesis inspired by biochemical processes.

Another, more recent meaning of the term bionics refers to merging organism and machine. This approach results in a hybrid system combining biological and engineering parts, which can also be referred as a cybernetic organism (cyborg). Practical realization of this was demonstrated in Kevin Warwick's implant experiments bringing about ultrasound input via his own nervous system.

See also

- Biomechatronics

- Biomedical engineering

- Biomimetics

- The Bionic Woman

- Bionic Woman (2007 TV series)

- Bionic architecture

- Biophysics

- Biotechnology

- Cyborg

- Cyborg (novel)

- History of technology

- Implant

- Index of environmental articles

- Prosthesis

- The Six Million Dollar Man

- Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering

References

- ↑ Twenty-First Century's Fuel Sufficiency Roadmap By Dr. Steve Esomba, Published 2012

- ↑ "bionics". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ Research Interests Archived 14 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine.. Duke.edu. Retrieved on 2011-04-23.

- ↑ Vincent, J. F. V.; Bogatyreva, O. A.; Bogatyrev, N. R.; Bowyer, A. & Pahl, A.-K. (2006). "Biomimetics—its practice and theory". Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 3 (9): 471–482. doi:10.1098/rsif.2006.0127. PMC 1664643. PMID 16849244.

- ↑ Sto Lotusan — Biomimicry Paint. TreeHugger. Retrieved on 2011-04-23.

- ↑ RFID Through Water and on Metal with 99.9% Reliability (Episode 015), RFID Radio

- ↑ Nanosensors inspired by butterfly wings (Wired UK) Archived 17 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine.. Wired.co.uk. Retrieved on 2011-04-23.

- ↑ Clark, O. G.; Kok, R.; Lacroix, R. (1999). "Mind and autonomy in engineered biosystems" (PDF). Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence. 12 (3): 389–399. doi:10.1016/S0952-1976(99)00010-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 August 2011.

- ↑ Howard T. Odum (15 May 1994). Ecological and general systems: an introduction to systems ecology. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 978-0-87081-320-7. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ↑ Mussel glue inspires bioadhesive gel for blood vessels | RobAid. RobAid.com. Retrieved on 2012-12-13.

- ↑ John J. Videler (October 2006). Avian Flight. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-929992-8. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ↑ Videler, J. J.; Stamhuis, EJ; Povel, GD (2004). "Leading-Edge Vortex Lifts Swifts". Science. 306 (5703): 1960–1962. doi:10.1126/science.1104682. PMID 15591209.

- ↑ Bret Tobalske's Hummingbird-research

- ↑ How Do Flies Turn? Archived 16 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine.. Journalism.berkeley.edu. Retrieved on 2011-04-23.

- ↑ Design inspired by nature Archived 21 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine., ESA

- ↑ "Bionic devices". Bionics Queensland. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ Bionic hand that uses wireless technology unveiled, Mail Online, 6 May 2010

- ↑ Biomimetics and NCRM, Nichi-In classification of Biomimetics Biomimicry tissue engineering, stem cells, cell therapy. Ncrm.org. Retrieved on 2011-04-23.

- ↑ Walsh, Fergus (22 July 2015). "Bionic eye implant world first". BBC News Online. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ↑ Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Bath Archived 17 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine.. Bath.ac.uk (21 February 2009). Retrieved on 2011-04-23.

Sources

- Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature. 1997. Janine Benyus.

- Biomimicry for Optimization, Control, and Automation, Springer-Verlag, London, UK, 2005, Kevin M. Passino

- "Ideas Stolen Right from Nature" (Wired)

- Bionics and Engineering: The Relevance of Biology to Engineering, presented at Society of Women Engineers Convention, Seattle, WA, 1983, Jill E. Steele

- Bionics: Nature as a Model. 1993. PRO FUTURA Verlag GmbH, München, Umweltstiftung WWF Deutschland

- Lipov A.N. At the origins of modern bionics. Bio-morphological formation in an artificial environment // Polygnosis. № 1-2. 2010. Ch. 1-2. Pp. 126-136.

- Lipov A.N. At the origins of modern bionics. Bio-morphological formation in an artificial environment // Polygnosis. № 3. 2010. Part 3. Рр. 80-91.

External links

Institutes

- Bionics Queensland

- Centre for Nature Inspired Engineering at UCL (University College London)

- Biological Robotics at the University of Tulsa

- Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering

- The Biomimicry Institute

- Center for Biologically Inspired Design

- Biologically Inspired Design group at the Design and Intelligence Lab, Georgia Tech

- Center for Biologically Inspired Materials & Material Systems

- Biologically Inspired Product Development at the University of Maryland

- The Biologically Inspired Materials Institute

- Center for Biologically Inspired Robotics Research at Case Western Reserve University

- Biologically Inspired Materials Institute

- Bio Inspired Engineering at the Applied University Kufstein, Austria

- Laboratory for Nature Inspired Engineering at The Pennsylvania State University