Biology in fiction

.jpg)

Biology appears in fiction, especially but not only in science fiction, both in the shape of real aspects of the science, used as themes or plot devices, and in the form of fictional elements, whether fictional extensions or applications of biological theory, or through the invention of fictional organisms. Major aspects of biology found in fiction include evolution, disease, genetics, parasitism and symbiosis (mutualism), and ecology.

Speculative evolution enables authors with sufficient skill to create what the critic Helen N. Parker calls biological parables, illuminating the human condition from an alien viewpoint. Fictional alien animals and plants, especially humanoids, have frequently been created simply to provide entertaining monsters. Zoologists such as Sam Levin have argued that, driven by natural selection on other planets, aliens might indeed tend to resemble humans to some extent.

Major themes of science fiction include messages of optimism or pessimism; Helen N. Parker has noted that in biological fiction, pessimism is by far the dominant outlook. Early works such as H. G. Wells's novels explored the grim consequences of Darwinian evolution, ruthless competition, and the dark side of human nature; Aldous Huxley's Brave New World was similarly gloomy about the effects of genetic engineering.

Fictional biology, too, has enabled major science fiction authors like Stanley Weinbaum, Isaac Asimov, John Brunner, and Ursula Le Guin to create what Parker called biological parables, with convincing portrayals of alien worlds able to support deep analogies with Earth and humanity.

Aspects of biology

Aspects of biology found in fiction include evolution, disease, genetics, parasitism, and mutualism.

Evolution

Evolution has been an important theme in fiction, including speculative evolution in science fiction, since the late 19th century, though it began before Charles Darwin's time, and reflects progressionist and Lamarckist views as well as Darwin's. Darwinian evolution is pervasive in literature, whether taken optimistically in terms of how humanity may evolve towards perfection, or pessimistically in terms of the dire consequences of the interaction of human nature and the struggle for survival. Other themes include the replacement of humanity, either by other species or by intelligent machines.[1][2]

Disease

Diseases, both real and fictional, play a significant role in fiction, some like Huntington's disease and tuberculosis appearing in many books and films. Pandemic plagues threatening all human life, such as The Andromeda Strain, are among the many fictional diseases described in literature and film.[3]

Tuberculosis was a common disease in the 19th century. In Russian literature, it appeared in several major works. Fyodor Dostoevsky used the theme of the consumptive nihilist repeatedly, with Katerina Ivanovna in Crime and Punishment; Kirillov in The Possessed, and both Ippolit and Marie in The Idiot. Turgenev did the same with Bazarov in Father and Sons.[4] In English literature of the Victorian era, major tuberculosis novels include Charles Dickens's 1848 Dombey and Son, Elizabeth Gaskell's 1855 North and South, and Mrs. Humphry Ward's 1900 Eleanor.[5][6]

Genetics

Aspects of genetics including mutation or hybridisation,[7][8] cloning (as in Brave New World),[9][10] genetic engineering,[11] and eugenics[12] have appeared in fiction since the 19th century. Genetics is a young science, having started in 1900 with the rediscovery of Gregor Mendel's study on the inheritance of traits in pea plants. During the 20th century it developed to create new sciences and technologies including molecular biology, DNA sequencing, cloning, and genetic engineering. The ethical implications were brought into focus with the eugenics movement. Since then, many science fiction novels and films have used aspects of genetics as plot devices, often taking one of two routes: a genetic accident with disastrous consequences; or, the feasibility and desirability of a planned genetic alteration. The treatment of science in these stories has been uneven and often unrealistic.[13][14][15] The film Gattaca did attempt to portray science accurately but was criticised by scientists.[16]

The lack of scientific understanding of genetics in the 19th century did not prevent science fiction works such as Mary Shelley's 1818 novel Frankenstein and H. G. Wells's 1896 The Island of Dr Moreau from exploring themes of biological experiment, mutation, and hybridisation, with their disastrous consequences, asking serious questions about the nature of humanity and responsibility for science.[15]

Parasitism

_(cropped).jpg)

Parasites appear frequently in fiction, from ancient times onwards as seen in mythical figures like the blood-drinking Lilith, with a flowering in the nineteenth century.[19] These include intentionally disgusting alien monsters in science fiction films, though these are sometimes less "horrible" than real examples in nature. Authors and scriptwriters have to some extent exploited parasite biology: lifestyles including parasitoid, behaviour-altering parasite, brood parasite, parasitic castrator, and many forms of vampire are found in books and films.[20][21][22][23][24] Some fictional parasites, like the deadly parasitoid Xenomorphs in Alien, have become well known in their own right.[18]

Symbiosis

Symbiosis (mutualism) appears in fiction, especially science fiction, as a plot device. It is distinguished from parasitism in fiction, a similar theme, by the mutual benefit to the organisms involved, whereas the parasite inflicts harm on its host. Fictional symbionts often confer special powers on their hosts.[24] After the Second World War, science fiction moved towards more mutualistic relationships, as in Ted White's 1970 By Furies Possessed, which viewed aliens positively.[24] The Force in the Star Wars universe is described by the fictional seer Obi-Wan Kenobi as "an energy field created by all living things". In The Phantom Menace, Qui-Gon Jinn says microscopic lifeforms called midi-chlorians, inside all living cells, allow characters with enough of these symbionts in their cells to feel and use the Force.[25] In Douglas Adams's humorous 1978 The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, the Babel fish lives in its human host's ear, feeding on the energy of its host's brain waves, in return translating any language to the host's benefit.[26]

Ecology

Ecology, the study of the relationships between organisms and their environment, appears in fiction in novels such as Frank Herbert's 1965 Dune, Kim Stanley Robinson's 1992 Red Mars, and Margaret Atwood's 2013 MaddAddam.[27] Dune brought ecology centre stage, with a whole planet struggling with its environment. Its lifeforms included giant sandworms for whom water is fatal and mouse-like animals able to survive in the planet's desert conditions.[28] The book was influential on the environmental movement of the time.[29]

Fictional organisms

.jpg)

Fiction, especially science fiction, has created large numbers of fictional species, both alien and terrestrial.[31][32] One branch of fiction, speculative evolution or speculative biology, consists specifically of the design of imaginary organisms in particular scenarios; this is sometimes informed by precise science.[33][34]

Functions

Fictional biology serves a variety of function in film and literature, including the supply of suitably terrifying monsters,[35] the communication of an author's worldview,[1][2] and the creation of aliens for biological parables to illuminate what it is to be human.[36] Real biology, such as of infectious diseases, equally provides a variety of contexts, from personal to highly dystopian, that can be exploited in fiction.[3]

Monsters and aliens

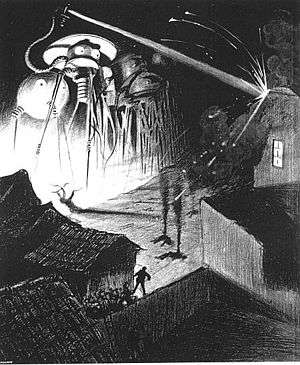

A common use of fictional biology in science fiction is to provide plausible alien species, sometimes simply as terrifying subjects, but sometimes for more reflective purposes.[35] Alien species include H. G. Wells's Martians in his 1898 novel The War of the Worlds,[37] the bug-eyed monsters of early 20th century science fiction,[38] fearsome parasitoids,[39] and a variety of giant insects, especially in early 20th century big bug movies.[40][41][42]

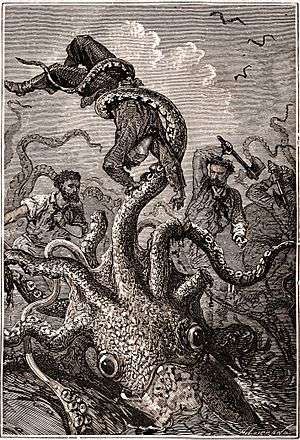

Humanoid aliens are common in science fiction.[43] On reason is that authors use the only example of intelligent life that they know, humans; an alternative, suggested by the zoologist Sam Levin, is that aliens might indeed tend to resemble humans, driven by natural selection.[44] Luis Villazon points out that animals that move necessarily have a front and a back; as with bilaterian animals on Earth, sense organs tend to gather at the front as they encounter stimuli there, forming a head. Legs reduce friction, and with legs, bilateral symmetry makes coordination easier. Sentient organisms will, Villazon argues, likely use tools, in which case they need hands and at least two other limbs to stand on. In short, a generally humanoid shape is likely, though octopus- or starfish-like bodies are also possible.[45]

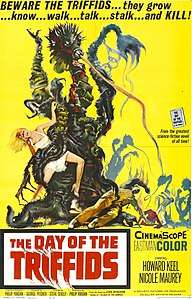

Fictional plants, too, such as John Wyndham's venomous, walking, carnivorous triffids[46] in his 1951 novel The Day of the Triffids,[47] have been created in numbers.[48] The idea of plants that could eat an incautious traveller began in the late 19th century, when even the potatoes in Erewhon could have "low cunning". Early tales included Phil Robinson's 1881 The Man-Eating Tree with its gigantic flytraps, Frank Aubrey's 1897 The Devil Tree of El Dorado, and Fred White's 1899 Purple Terror. Algernon Blackwood's 1907 story "The Willows" powerfully tells of malevolent trees that manipulate people's minds.[49]

Cephalopod-like sea monster in Jules Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea drawn by Alphonse de Neuville, 1871

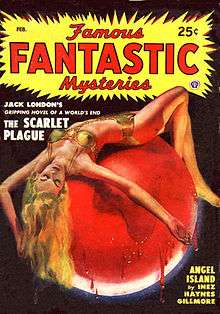

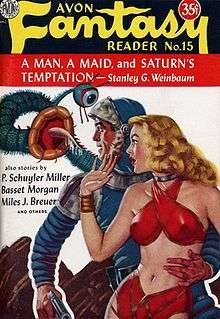

Cephalopod-like sea monster in Jules Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea drawn by Alphonse de Neuville, 1871 A bug-eyed monster, a trope of early science fiction. Illustration shows Stanley G. Weinbaum's 1951 story "A Man, A Maid, and Saturn's Temptation".

A bug-eyed monster, a trope of early science fiction. Illustration shows Stanley G. Weinbaum's 1951 story "A Man, A Maid, and Saturn's Temptation". Man-eating plant: 1962 poster by Steve Sekely for a film adaptation of John Wyndham's 1951 novel The Day of the Triffids

Man-eating plant: 1962 poster by Steve Sekely for a film adaptation of John Wyndham's 1951 novel The Day of the Triffids

Optimism and pessimism

A major theme of science fiction and of speculative biology is to convey a message of optimism or pessimism according to the author's worldview.[1][2] Whereas optimistic visions of technological progress are common enough in hard science fiction, pessimistic views of the future of humanity are far more usual in fiction based on biology.[50]

A rare optimistic note is struck by the evolutionary biologist J. B. S. Haldane in his tale, The Last Judgement, in the 1927 collection Possible Worlds. Both Arthur C. Clarke's 1953 Childhood's End and Brian Aldiss's 1959 Galaxies Like Grains of Sand, too, optimistically imagine that humans will evolve godlike mental capacities.[1]

The grim possibilities of Darwinian evolution with its ruthless "survival of the fittest" has been explored repeatedly from the beginnings of science fiction, as in H. G. Wells's novels The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Dr Moreau (1896), and The War of the Worlds (1898); these all pessimistically explore the possible dire consequences of the darker sides of human nature in the struggle for survival.[1] Aldous Huxley's 1931 novel Brave New World is similarly gloomy about the oppressive consequences of advances in genetic engineering applied to human reproduction.[51]

Biological parables

The literary critic Helen N. Parker suggested in 1977 that speculative biology could serve as biological parables which throw light on the human condition. Such a parable brings aliens and humans into contact, allowing the author to view humanity from an alien perspective. She noted that the difficulty of doing this at length meant that only a few major authors had attempted it, naming Stanley Weinbaum, Isaac Asimov, John Brunner, and Ursula Le Guin. In her view, all four had impressively full characterizations of alien beings. Weinbaum had created a "bizarre assortment" of intelligent beings, unlike Brunner's crablike but extinct Draconians. What united all four writers, she argued, was that the novels centred on the interactions between aliens and humans, creating deep analogies between the two kinds of life and from there commenting on humanity now and in the future.[36]

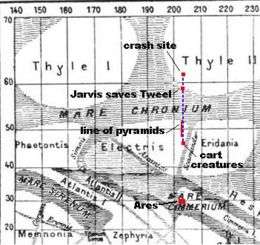

Weinbaum's 1934 A Martian Odyssey explored the question of how aliens and humans could communicate, given that their thought processes were utterly different. In Parker's view, his approach was a radical departure from the conventional bug-eyed monsters of that epoch. Instead of writing about ugly aliens who simply mirrored human characteristics, he imaginatively created an "unforgettable" cast of Martians, headed by the "remarkable" Tweel. She argued that by "vividly and believably" conveying the alienness of the Martians, involving the reader in their cultures, he transformed science fiction.[52] She cited the historian Samuel Moskowitz's comment that "Weinbaum's life forms, to the delight of the readers, display a psychology and sense of values if not incomprehensible, then frequently antipodal to that of earthmen. They thought differently and were motivated differently. Their entire philosophy of life was completely out of the range of human experience."[52][53]

Asimov's 1972 The Gods Themselves both makes the aliens major characters, and explores parallel universes. In Parker's view he carefully grounds the account by setting the first and third parts on Earth,[lower-alpha 1] and the middle part, "The Gods Themselves", in the "para-universe", enabling him to contrast the worlds and so to comment on human society and fallibility. The "parabeings" have a novel biology, "closely bound in biological and social triads that gradually merge through a series of 'meltings' into single adult beings, or 'Hard Ones'." One of each triad is the 'Emotional', who provides sensitivity and the "emotional energy" needed for a melting; one the 'Rational', who carries memories of previous meltings; and one the 'Parental', who bears the seeds of new parabeings and brings them up. Parker compares the triad to transactional analysis, a then-popular approach in psychoanalysis.[54]

Brunner's 1974 Total Eclipse creates a whole alien world, extrapolated from terrestrial threats. The planet Sigma Draconis III is dying, and its native Draconians, who have caused the damage to the planet, have become extinct. The human protagonist (Ian Macauley) has to rediscover the Draconian's social and biological systems and live as one of them to understand why they went extinct. As he does so, both the expedition members and the reader, Parker argued, speculate and reason about the interpretation of the artefacts found on the planet. The Draconians turn out to have been sequential hermaphrodites, first male then briefly female; and they practised eugenics, breeding for intelligence and rationality. In the process, they so narrowed their genome that their fertility declined and their vulnerability to disease grew, causing their own extinction. The story simultaneously develops the microcosm of the world of the expedition crew with its window into human behaviour, enabling comparisons between the two worlds and reflection on humanity's fate.[55]

.jpg)

In her 1969 The Left Hand of Darkness, Le Guin presents her vision of a universe of planets all inhabited by "men", descendants from the planet Hain. In the book, the ambassador Genly Ai from the civilised Ekumen worlds visits the "backward- and inward-looking" people of Gethen, only to end up in danger, from which he escapes by crossing the polar ice cap on a desperate but well-planned expedition with an exiled Gethenian Lord Chancellor, Estraven. They are ambisexual with no fixed gender, and go through periods of oestrus, called "kemmer", at which point an individual comes temporarily to function as either a male or a female, depending on whether they first encounter a male- or female-functioning partner during their period of kemmer. The invented biology reflects and exemplifies, according to Parker, the opposing but united dualities of Taoism such as light and darkness, maleness and femaleness, yin and yang. So too do the opposed characters of Genly Ai with his carefully objective reports, and of Estraven with his or her highly personal diary, as the story unfolds, illuminating humanity through adventure and science fiction strangeness.[56]

Structure and themes

Modern novels sometimes make use of biology to provide structure and themes. An example is Richard Flanagan's "extraordinary"[57] 2001 novel Gould's Book of Fish, which makes use of the illustrations from the real artist and convict William Buelow Gould's book of 26 paintings of fish for chapter headings and chapter themes.[57]

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stableford, Brian M.; Langford, David R. (5 July 2018). "Evolution". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Gollancz. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 Levine, George (5 October 1986). "Darwin and the Evolution of Fiction". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- 1 2 Dugdale, John (1 August 2014). "Plague fiction – why authors love to write about pandemics". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ O'Connor, Terry (2016). Tuberculosis:Overview. International Encyclopedia of Public Health. Academic Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-12-803708-9.

- ↑ Lawlor, Clark. "Katherine Byrne, Tuberculosis and the Victorian Literary Imagination". British Society for Literature and Science. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ↑ Byrne, Katherine (2011). Tuberculosis and the Victorian Literary Imagination. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-67280-2.

- ↑ Parker 1977, p. 13.

- ↑ Schmeink, Lars (2017). Biopunk Dystopias Genetic Engineering, Society and Science Fiction. Liverpool University Press. pp. 8–. ISBN 978-1-78138-332-2.

- ↑ Huxley, Aldous (2005). Brave New World and Brave New World Revisited. HarperPerennial. p. 19. ISBN 978-0060776091.

- ↑ Bhelkar, Ratnakar D. (2009). Science Fiction: Fantasy and Reality. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. p. 58. ISBN 9788126910366.

- ↑ "Genetic Engineering". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. 15 May 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl (November 10, 2008). "Now: The Rest of the Genome". The New York Times.

- ↑ Koboldt, Daniel (1 August 2014). "Genetics Myths in Fiction Writing". Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ↑ Koboldt, Daniel (2018). "Putting the Science in Fiction". Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- 1 2 Moraga, Roger. "Modern Genetics in the World of Fiction". Clarkesworld magazine. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ Kirby, David A. (July 2000). "The New Eugenics in Cinema: Genetic Determinism and Gene Therapy in "GATTACA"". Science Fiction Studies. 27 (2): 193–215. JSTOR 4240876.

- ↑ Budanovic, Nikola (10 March 2018). "An explanation emerges for how the 12th century Paisley Abbey in Scotland could feature a gargoyle out of the film "Alien"". The Vintage News. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- 1 2 "'Alien' gargoyle on ancient Paisley Abbey". British Broadcasting Corporation. 23 August 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ↑ "Parasitism and Symbiosis". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. 10 January 2016.

- ↑ Guarino, Ben (19 May 2017). "Disgusting 'Alien' movie monster not as horrible as real things in nature". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Glassy, Mark C. (2005). The Biology of Science Fiction Cinema. McFarland. pp. 186 ff. ISBN 978-1-4766-0822-8.

- ↑ Moisseeff, Marika (23 January 2014). "Aliens as an Invasive Reproductive Power in Science Fiction". HAL Archives-Ouvertes.

- ↑ Williams, Robyn; Field, Scott (27 September 1997). "Behaviour, Evolutionary Games and .... Aliens". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 Stableford, Brian M. (10 January 2016). "Parasitism and Symbiosis". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Gollancz. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ Brooks, Terry (1999). Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace. Ballantine Books.

- ↑ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy: Fit the First BBC Radio 4 program, broadcast 8 March 1978

- ↑ DeNardo, John (23 July 2014). "Recent Ecological Fiction". Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ James, Edward; Farah Mendlesohn (2003). The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction. Cambridge University Press. pp. 183–184. ISBN 0-521-01657-6.

- ↑ Robert L. France, ed. (2005). Facilitating Watershed Management: Fostering Awareness and Stewardship. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 105. ISBN 0-7425-3364-6.

- ↑ Stümpke, Harald (pseudonym of Gerolf Steiner), Bau und Leben der Rhinogradentia with preface and illustrations by Gerolf Steiner. Fischer, Stuttgart, (1961). ISBN 3-437-30083-0.

- ↑ Vint, Sherryl (2010). Animal Alterity: Science Fiction and Human-Animal Studies. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1846318153.

- ↑ Vint, Sherryl (July 2008). ""The Animals in That Country": Science Fiction and Animal Studies". Science Fiction Studies. 35 (2): 177–188. JSTOR 25475137.

- ↑ Nastrazzurro, Sigmund. "A xenobiological conference call". Furahan Biology and Allied Matters. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ "Science Meets Speculation in All Your Yesterdays – Phenomena: Laelaps". Retrieved 2015-06-08.

- 1 2 Hardwick, Kayla M. (22 October 2014). "Natural selection at the movies: Only the bad guys evolve". Nothing in Biology Makes Sense [except in the light of evolution]. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- 1 2 Parker 1977, p. 63.

- ↑ Westfahl, Gary (2005). "Aliens in Space". In Gary Westfahl. The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Themes, Works, and Wonders. 1. Greenwood Press. pp. 14–16. ISBN 0-313-32951-6.

- ↑ Urbanski, Heather (2007). Plagues, Apocalypses and Bug-Eyed Monsters: How Speculative Fiction Shows Us Our Nightmares. McFarland. pp. 149–168 and passim. ISBN 978-0-7864-2916-5.

- ↑ Sercel, Alex (19 May 2017). "Parasitism in the Alien Movies". Signal to Noise Magazine.

- ↑ Gregersdotter, Katarina; Höglund, Johan; Hållén, Nicklas (2016). Animal Horror Cinema: Genre, History and Criticism. Springer. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-137-49639-3.

- ↑ Warren, Bill; Thomas, Bill (2009). Keep Watching the Skies!: American Science Fiction Movies of the Fifties, The 21st Century Edition. McFarland. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-4766-2505-8.

- ↑ Crouse, Richard (2008). Son of the 100 Best Movies You've Never Seen. ECW Press. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-55490-330-6.

- ↑ Munkittrick, Kyle (12 July 2011). "The Only Sci-Fi Explanation of Hominid Aliens that Makes Scientific Sense". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ↑ Griffin, Andrew (1 November 2017). "What would aliens look like? More similar to us than people realise, scientists suggest". The Independent. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ↑ Villazon, Luis (16 December 2017). "What are the odds that aliens are humanoid?". Science Focus (BBC Focus Magazine Online). Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ↑ Anon (4 September 2013). "'They're like triffids' - garderner grows 6ft courgette". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ↑ Stock, Adam (November 2015). "The Blind Logic of Plants: Enlightenment and Evolution in John Wyndham's The Day of the Triffids". Science Fiction Studies. 42 (3): 433–457. doi:10.5621/sciefictstud.42.3.0433. JSTOR 10.5621/sciefictstud.42.3.0433.

- ↑ Hoffelder, Kate (20 August 2015). "Infographic: Eighty Fictional Plants". The Digital Reader. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ↑ Karpenko, Lara; Claggett, Shalyn; Chang, Elizabeth (2016). "4: Killer Plants of the Late Nineteenth Century". Strange Science: Investigating the Limits of Knowledge in the Victorian Age. University of Michigan Press. pp. 81–101. ISBN 978-0-472-13017-7.

- ↑ Parker 1977, p. 80 and passim.

- ↑ Parker 1977, p. 80.

- 1 2 Parker 1977, pp. 64–66.

- ↑ Moskowitz, Samuel (1934). Introduction. A Martian Odyssey. Lancer Books.

- 1 2 Parker 1977, pp. 67–71.

- ↑ Parker 1977, pp. 73–76.

- ↑ Parker 1977, pp. 70–77.

- 1 2 MacFarlane, Robert (26 May 2002). "Con fishing | Gould's Book of Fish". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

Sources

- Parker, Helen N. (1977). Biological Themes in Modern Science Fiction. UMI Research Press.