Berserker

Berserkers (or "berserks") were champion Norse warriors who are primarily reported in Icelandic sagas to have fought in a trance-like fury, a characteristic which later gave rise to the English word "berserk."

These champions would often go into battle without mail coats. Berserkers are attested to in numerous Old Norse sources, as were the Úlfhéðnar ("wolf-coats").

Etymology

The English word berserk is derived from the Old Norse words ber-serkr (plural ber-serkir) possibly meaning a "bear-shirt"—i.e., a wild warrior or champion of the viking age, although its interpretation remains controversial.[2] The element ber- was interpreted by the thirteenth-century historian Snorri Sturluson as "bare", which he understood to mean that the warriors went into battle bare-chested, or without armor.[3][2] This word is also used in ber-skjaldaðr that means "bare of shield", or without a shield. Others derive it from the preferred berr (Germ, bär = ursus, the bear),[2] and Snorri's view has been largely abandoned.[4]

Early beginnings

It is proposed by some authors that the northern warrior tradition originated in hunting magic.[5][6] Three main animal cults appeared: the bear, the wolf, and the wild boar.[5]

The bas relief carvings on Trajan's column in Rome depict scenes of Trajan's conquest of Dacia in 101–106 CE. The scenes show his Roman soldiers plus auxiliaries and allies from Rome's border regions, including tribal warriors from both sides of the Rhine. There are warriors depicted as bare-foot, bare-chested, bearing weapons and helmets that are associated with the Germani. Scene 36 on the column shows some of these warriors standing together, with some wearing bearhoods and some wearing wolfhoods. Nowhere else in history are Germanic bear-warriors and wolf-warriors fighting together recorded until 872 CE, with Thórbiörn Hornklofi's description of the battle of Hafrsfjord when they fight together for King Harald Fairhair of Norway.[7]

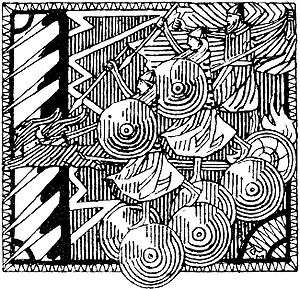

In the spring of 1870, four cast-bronze-dies, the Torslunda plates, were found by Erik Gustaf Pettersson and Anders Petter Nilsson in a cairn on the lands of the farm No 5 Björnhovda in Torslunda parish, Öland, Sweden.[8][1] Two relevant images are depicted below, along with two associated woodcuts made two years later in 1872.

Berserkers – bear warriors

It is proposed by some authors that the berserkers drew their power from the bear and were devoted to the bear cult, which was once widespread across the northern hemisphere.[6][9] The berserkers maintained their religious observances despite their fighting prowess, as the Svarfdæla saga tells of a challenge to single-combat that was postponed by a berserker until three days after Yule.[5] The bodies of dead berserkers were laid out in bearskins prior to their funeral rites.[10] The bear-warrior symbolism survives to this day in the form of the bearskin caps worn by the guards of the Danish and British monarchs,[5].

In battle, the berserkers were subject to fits of frenzy. They would howl like wild beasts, foamed at the mouth, and gnawed the iron rim of their shields. According to belief, during these fits they were immune to steel and fire, and made great havoc in the ranks of the enemy. When the fever abated they were weak and tame. Accounts can be found in the sagas.[2]

To "go berserk" was to "hamask", which translates as "change form", in this case, as with the sense "enter a state of wild fury". Some scholars have interpreted those who could transform as a berserker was typically as "hamrammr" or "shapestrong" – literally able to shape-shift into a bear's form.[11]:126 For example, the band of men that go with Skallagrim in Egil's Saga to see King Harald about his brother Thorolf’s murder are described as “the hardest of men, with a touch of the uncanny about a number of them ... they [were] built and shaped more like trolls than human beings”. This has sometimes been interpreted as the band of men being "hamrammr", though there is no major consensus.[12][13]

Úlfhéðnar – wolf warriors

Wolf warriors appear among the legends of the Indo-Europeans, Turks, Mongols, and North American Indians.[14] The Germanic wolf-warriors have left their trace through shields and standards that were captured by the Romans and displayed in the armilustrium in Rome.[15]

The Úlfhéðnar (singular Úlfheðinn), another term associated with berserkers, mentioned in the Vatnsdæla saga, Haraldskvæði and the Völsunga saga, were said to wear the pelt of a wolf when they entered battle.[16] Úlfhéðnar are sometimes described as Odin's special warriors: "[Odin's] men went without their mailcoats and were mad as hounds or wolves, bit their shields...they slew men, but neither fire nor iron had effect upon them. This is called 'going berserk'."[11]:132 In addition, the helm-plate press from Torslunda depicts (below) a scene of Odin with a berserker with a wolf pelt and a spear as distinguishing features: “a wolf skinned warrior with the apparently one-eyed dancer in the bird-horned helm, which is generally interpreted as showing a scene indicative of a relationship between berserkgang ... and the god Odin”.[17][18]

Svinfylking – boar warriors

In Norse mythology, the wild boar was an animal sacred to the Vanir. The powerful god Freyr owned the boar Gullinbursti and the goddess Freyja owned Hildisvíni ("battle swine"), and these boars can be found depicted on Swedish and Anglo-Saxon ceremonial items. The boar-warriors fought at the lead of a battle formation known as Svinfylking ("the boar's head") that was wedge-shaped, and two of their champions formed the rani ("snout"). They have been described as the masters of disguise, and of escape with an intimate knowledge of the landscape.[6] Similar to the berserker and the ulfhednar, the svinfylking boar-warriors used the strength of their animal, the boar, as the foundation of their martial arts.[6][19]

Attestations

Berserkers appear prominently in a multitude of other sagas and poems, many of which describe berserkers as ravenous men who loot, plunder, and kill indiscriminately. Later, by Christian interpreters, the berserker was viewed as a "heathen devil".[20]

The earliest surviving reference to the term "berserker" is in Haraldskvæði, a skaldic poem composed by Thórbiörn Hornklofi in the late 9th century in honor of King Harald Fairhair, as ulfheðnar ("men clad in wolf skins"). This translation from the Haraldskvæði saga describes Harald's berserkers:[21]

I'll ask of the berserks, you tasters of blood,

Those intrepid heroes, how are they treated,

Those who wade out into battle?

Wolf-skinned they are called. In battle

They bear bloody shields.

Red with blood are their spears when they come to fight.

They form a closed group.

The prince in his wisdom puts trust in such men

Who hack through enemy shields.

The "tasters of blood" in this passage are thought to be ravens, which feasted on the slain.[21]

The Icelandic historian and poet Snorri Sturluson (1179–1241) wrote the following description of berserkers in his Ynglinga saga:

His (Odin's) men rushed forwards without armour, were as mad as dogs or wolves, bit their shields, and were strong as bears or wild oxen, and killed people at a blow, but neither fire nor iron told upon them. This was called Berserkergang.[22]

King Harald Fairhair's use of berserkers as "shock troops" broadened his sphere of influence. Other Scandinavian kings used berserkers as part of their army of hirdmen and sometimes ranked them as equivalent to a royal bodyguard. It may be that some of those warriors only adopted the organization or rituals of berserk männerbünde, or used the name as a deterrent or claim of their ferocity.

Emphasis has been placed on the frenzied nature of the berserkers, hence the modern sense of the word "berserk". However, the sources describe several other characteristics that have been ignored or neglected by modern commentators. Snorri's assertion that "neither fire nor iron told upon them" is reiterated time after time. The sources frequently state that neither edged weapons nor fire affected the berserks, although they were not immune to clubs or other blunt instruments. For example:

These men asked Halfdan to attack Hardbeen and his champions man by man; and he not only promised to fight, but assured himself the victory with most confident words. When Hardbeen heard this, a demoniacal frenzy suddenly took him; he furiously bit and devoured the edges of his shield; he kept gulping down fiery coals; he snatched live embers in his mouth and let them pass down into his entrails; he rushed through the perils of crackling fires; and at last, when he had raved through every sort of madness, he turned his sword with raging hand against the hearts of six of his champions. It is doubtful whether this madness came from thirst for battle or natural ferocity. Then with the remaining band of his champions he attacked Halfdan, who crushed him with a hammer of wondrous size, so that he lost both victory and life; paying the penalty both to Halfdan, whom he had challenged, and to the kings whose offspring he had violently ravished...[23]

Similarly, Hrolf Kraki's champions refuse to retreat "from fire or iron". Another frequent motif refers to berserkers blunting their enemy's blades with spells or a glance from their evil eyes. This appears as early as Beowulf where it is a characteristic attributed to Grendel. Both the fire eating and the immunity to edged weapons are reminiscent of tricks popularly ascribed to fakirs.

In 1015, Jarl Eiríkr Hákonarson of Norway outlawed berserkers. Grágás, the medieval Icelandic law code, sentenced berserker warriors to outlawry. By the 12th century, organised berserker war-bands had disappeared.

The Lewis Chessmen, found on the Isle of Lewis (Outer Hebrides, Scotland) but thought to be of Norse manufacture, include berserkers depicted biting their shields.

Theories

Scholar Hilda Ellis-Davidson draws a parallel between berserkers and the mention by the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII (CE 905–959) in his book De cerimoniis aulae byzantinae ("Book of Ceremonies of the Byzantine court") of a "Gothic Dance" performed by members of his Varangian Guard (Norse warriors in the service of the Byzantine Empire), who took part wearing animal skins and masks: she believes this may have been connected with berserker rites.[24]

The rage the berserker experienced was referred to as berserkergang ("going berserk"). This condition has been described as follows:

This fury, which was called berserkergang, occurred not only in the heat of battle, but also during laborious work. Men who were thus seized performed things which otherwise seemed impossible for human power. This condition is said to have begun with shivering, chattering of the teeth, and chill in the body, and then the face swelled and changed its colour. With this was connected a great hot-headedness, which at last gave over into a great rage, under which they howled as wild animals, bit the edge of their shields, and cut down everything they met without discriminating between friend or foe. When this condition ceased, a great dulling of the mind and feebleness followed, which could last for one or several days.[25]

When Viking villages went to war in unison, the berserkers often wore special clothing, for instance furs of a wolf or bear, to indicate that this person was a berserker, and would not be able to tell friend from foe when in rage "bersærkergang". In this way, other allies would know to keep their distance.[26]

Some scholars propose that certain examples of berserker rage had been induced voluntarily by the consumption of drugs such as the hallucinogenic mushroom Amanita muscaria[25][27][28] or massive amounts of alcohol.[29] However, this is much debated[30] and has been thrown into doubt by the discovery of seeds belonging to the plant henbane Hyoscyamus niger in a Viking grave that was unearthed near Fyrkat, Denmark in 1977.[31] Given that crushing and rubbing henbane petals onto the skin provides a numbing effect along with a mild sensation of flying, this finding has led to the theory that henbane rather than mushrooms or alcohol was used to incite the legendary rage.[30] While such practices would fit in with ritual usages, other explanations for the berserker's madness have been put forward, including self-induced hysteria, epilepsy, mental illness, or genetics.[32]

Jonathan Shay makes an explicit connection between the berserker rage of soldiers and the hyperarousal of post-traumatic stress disorder.[33] In Achilles in Vietnam, he writes:

If a soldier survives the berserk state, it imparts emotional deadness and vulnerability to explosive rage to his psychology and permanent hyperarousal to his physiology — hallmarks of post-traumatic stress disorder in combat veterans. My clinical experience with Vietnam combat veterans prompts me to place the berserk state at the heart of their most severe psychological and psychophysiological injuries.[34]

See also

- Dutch courage

- Furor Teutonicus

- Going postal

- Harii, a Germanic tribe

- Running amok

- Therianthropy

- Warp spasm

- Werewolf

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Helmets and swords in Beowulf" by Knut Stjerna out of a Festschrift to Oscar Monteliusvägen published in 1903

- 1 2 3 4 An Icelandic-English Dictionary by Richard Cleasby and Gudbrand Vigfusson (1874) p. 61

- ↑ Blaney, Benjamin (1972). The Berserker: His Origin and Development in Old Norse Literature. Ph.D. Diss. University of Colorado. p. 20.

- ↑ Simek 1995, p. 47.

- 1 2 3 4 Prudence Jones & Nigel Pennick (1997). "Late Germanic Religion". A History of Pagan Europe. Routledge; Revised edition. pp. 154–56. ISBN 978-0415158046.

- 1 2 3 4 A. Irving Hallowell (1925). "Bear Ceremonialism in the Northern Hemisphere". American Anthropologist. 28: 2. doi:10.1525/aa.1926.28.1.02a00020.

- ↑ Speidel 2004, pp. 3–7.

- ↑ MedievHistories (12 June 2014). "Odin from Levide". Medieval Histories. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ↑ Nioradze, Georg. "Der Schamanismus bei den sibirischen Völkern", Strecker und Schröder, 1925.

- ↑ Danielli, M, "Initiation Ceremonial from Norse Literature", Folk-Lore, v56, 1945 pp. 229–45.

- 1 2 Davidson, Hilda R.E. (1978). Shape Changing in Old Norse Sagas. Cambridge: Brewer; Totowa: Rowman and Littlefield.

- ↑ Sturluson, Snorri (1976). Egil's Saga. Harmondsworth (Penguin). p. 66.

- ↑ Jakobsson, Ármann (2011). "Beast and man: Realism and the occult in Egils saga". Scandinavian Studies. 83 (1): 34.

- ↑ Speidel 2004, p. 10.

- ↑ Speidel 2004, p. 15.

- ↑ Simek 1995, p. 435.

- ↑ Grundy, Stephan (1998). Shapeshifting and Berserkgang. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. p. 18.

- ↑ Simek 1995, p. 48.

- ↑ Beck, H. 1965 Das Ebersignum im Germanischen. Ein Beitrag zur germanischen TierSymbolik. Berlin: W. de Gruyter.

- ↑ Blaney, Benjamin (1972). The Berserkr: His Origin and Development in Old Norse Literature. Ph.D. Diss. University of Colorado. p. iii.

- 1 2 Page, R. I. (1995). Chronicles of the Vikings. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press. p. 109. ISBN 9780802071651.

- ↑ Laing, Samuel (1889). The Heimskringla or the Sagas of the Norse Kings. London: John. C. Nimo. p. 276

- ↑ Elton, Oliver (1905) The Nine Books of the Danish History of Saxo Grammaticus. New York: Norroena Society. See Medieval and Classical Literature Library Release #28a for full text.

- ↑ Ellis-Davidson, Hilda R. (1967) Pagan Scandinavia, p. 100. Frederick A. Praeger Publishers ASIN B0000CNQ6I

- 1 2 Fabing, Howard D. (1956). "On Going Berserk: A Neurochemical Inquiry". Scientific Monthly. 83 (5): 232–37. Bibcode:1956SciMo..83..232F. doi:10.2307/21684 (inactive 2018-09-22). JSTOR 21684.

- ↑ Vikingernes Verden. Else Roesdahl. Gyldendal 2001

- ↑ Hoffer, A. (1967). The Hallucinogens. Academic Press. pp. 443–54. ISBN 978-1483256214.

- ↑ Howard, Fabing (Nov 1956). "On Going Berserk: A Neurochemical Inquiry". Scientific Monthly. 113 (5): 232. Bibcode:1956SciMo..83..232F.

- ↑ Wernick, Robert (1979) The Vikings. Alexandria VA: Time-Life Books. p. 285

- 1 2 1977-, Kaplan, Matt (2015-10-27). Science of the magical : from the Holy Grail to love potions to superpowers (First Scribner hardcover ed.). New York. ISBN 9781476777108. OCLC 904813040.

- ↑ S., Price, Neil (2002). The Viking way : religion and war in late Iron Age Scandinavia. Uppsala universitet. Uppsala: Dept. of Archaeology and Ancient History. ISBN 978-9150616262. OCLC 52987118.

- ↑ Foote, Peter G. and Wilson, David M. (1970) The Viking Achievement. London: Sidgewick & Jackson. p. 285.

- ↑ Shay, J. (2000). "Killing rage: physis or nomos—or both" pp. 31–56 in War and Violence in Ancient Greece. Duckworth and the Classical Press of Wales. ISBN 0715630466

- ↑ Shay, Jonathan (1994). Achilles in Vietnam. New York: Scribner. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-689-12182-1.

Bibliography

- Speidel, Michael P (2004), Ancient Germanic Warriors: Warrior Styles from Trajan's Column to Icelandic Sagas, London: Routledge, ISBN 978-0415486828

- Simek, Rudolf (1995), Lexikon der germanischen Mythologie, Stuttgart: Alfred Kröner, ISBN 978-3-520-36802-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tierkrieger. |

- Vandle helmet with bronze plates depicting wild Boar warriors, the Svinfylking 8th Century CE. Valsgarde, Sweden

- Berserkene – hva gikk det av dem? (Jon Geir Høyersten: Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association)

- Berserkergang (Viking Answer Lady)

- Berserkers-wolf-people

_sid_103).jpg)

_sid_103).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)