Belizean–Guatemalan territorial dispute

The Belizean–Guatemalan territorial dispute is an unresolved binational territorial dispute between the states of Belize and Guatemala, neighbours in Central America. The territory of Belize has been claimed in whole or in part by Guatemala since 1821.

Early colonial era

The present dispute originates with imperial Spain's claim to all New World territories west of the line established in the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494. England, like other powers of the late 15th century, did not recognize the treaty that divided the world between Spain and Portugal. After Mayan Indian tribes had massacred Spanish conquistadors and missionaries in Tipu and surrounding areas, shipwrecked English seamen, then English and Scottish Baymen, settled by 1638, making their presence permanent by 1779, with a short military alliance with Amerindians from the Mosquito Coast south of Belize, and often welcoming former British privateers.[1]

In the Godolphin Treaty of 1670, Spain confirmed England was to hold all territories in the Western Hemisphere that it had already settled; however, the treaty did not define what areas were settled, and despite the historic evidence that England occupied Belize when they signed the Godolphin Treaty, Spain later used this vagueness to maintain its claim on the entirety of Belize.[1] Meanwhile, by the 18th century, the Baymen and Mayans increasingly became enemies, as the Mayans reverted to their traditional hostility to foreign settlers, although they continued to sell slaves to the Baymen.

Without recognition of either the British or Spanish governments, the Baymen in Belize started electing magistrates as early as 1738.[1] After the Treaty of Paris and with the following conditions re-affirmed in the 1783 Treaty of Versailles, Britain agreed to abandon British forts in Belize that protected the Baymen and give Spain sovereignty over the soil, while Spain agreed the Baymen could continue logging wood in present-day Belize. However, the Baymen agreed to none of this, and after the 1783 Treaty of Versailles, the governor of British-controlled Jamaica sent a superintendent to control the settlers, but had his authority denied by the farmers and loggers.[1]

When Spain attempted to eject them and seize their land and wealth, the Baymen revolted. Spain's last military attempt to dislodge the rebellious settlers was the 1798 Battle of St. George's Caye, which ended with Spain failing to re-take the territory. The Baymen never asked for nor received a formal treaty with Spain after this, and the UK was only able to gain partial control of the settlers by 1816; British people continued operating their own local government without permission from either imperial power, though the British tacitly accepted the situation. This lasted until they joined the British Empire in 1862.[1] The territorial dispute's origins lay in the 18th-century treaties in which Great Britain acceded to Spain's assertion of sovereignty while British settlers continued to occupy the sparsely settled and ill-defined area. The 1786 Convention of London, which affirmed Spanish sovereignty was never renegotiated, but Spain never attempted to reclaim the area after 1798. Subsequent treaties between Britain and Spain failed to mention the British settlement. By the time Spain lost control of Mexico and Central America in 1821, Britain had extended its control over the area, albeit informally and unsystematically. By the 1830s, Britain regarded the entire territory between the Hondo River and Sarstoon River as British.[1]

The independent republics that emerged from the disintegrating Spanish Empire in the 1820s claimed that they had inherited Spain's sovereign rights in the area. The UK, however, never accepted such a doctrine. Based on this doctrine of inheritance, Mexico and Guatemala asserted claims to Belize. Mexico once claimed the portion of British Honduras north of the Sibun River but dropped the claim in a treaty with Britain in 1893. Since then, Mexico has stated that it would revive the claim only if Guatemala were successful in obtaining all or part of the nation. Still, Mexico was the first nation to recognise Belize as an independent country.[1]

Late colonial era

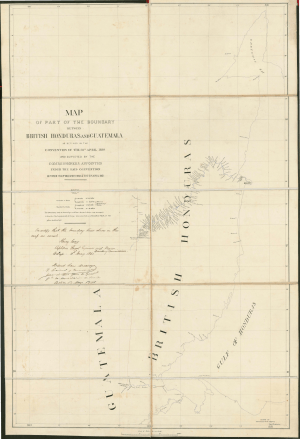

Guatemala declared its independence from Spain in 1821, and Great Britain did not accept the Baymen of what is now Belize as a crown colony until 1862, 64 years after the Baymen's last hostilities with Spain. This crown colony became known as "British Honduras".

Under the terms of the Wyke–Aycinena Treaty of 1859, Guatemala agreed to recognize British Honduras, and Great Britain promised to build a road from Guatemala to the nearby Baymen town of Punta Gorda. This treaty was approved by General Rafael Carrera ("supreme and perpetual leader" of Guatemala), and Queen Victoria of Great Britain without regard to the Maya peoples living there. In 1940, Guatemala claimed that the 1859 treaty was void because the British failed to comply with economic assistance provisions found in Clause VII of the Treaty. Belize, once independent, claimed this was not a treaty they were bound by since they did not sign it. Belize further argued that International Court of Justice rulings[2][3][4] and principles of international law, such as uti possidetis juris and the right of nations to self-determination, demand that Guatemala honour the boundaries in the 1859 treaty even if Great Britain never built the road as promised.

At the centre of Guatemala's oldest claim was the 1859 treaty between the United Kingdom and Guatemala. From Britain's viewpoint, this treaty merely settled the boundaries of an area already under British dominion. Today's independent Belize government holds the viewpoint that treaties signed by the UK are not binding on them, that the International Court of Justice's precedent is that the 1859 treaty is binding on Guatemala unless Guatemala can firmly prove the 1859 treaty was forced upon them by the UK, that international law says any breaches in the 1859 treaty by the UK would not excuse Guatemala's breaches and the UK never made "material breaches",[5] that Guatemala never inherited Spain's claim because Guatemala never occupied that part of Spain's New World colonies, and the right of a people to self-determination.[6]

Guatemala, in opposition to both the UK and Belize positions, has an older view that this agreement was a treaty of cession through which Guatemala would give up its territorial claims only under certain conditions, including the construction of a road from Guatemala to the Caribbean coast. The UK never built the road, and Guatemala said it would repudiate the treaty in 1884 but never followed up on the threat.

20th century to 1975

The dispute appeared to have been forgotten until the 1930s, when the government of General Jorge Ubico claimed that the treaty was invalid because the road had not been constructed. Britain argued that because neither the short-lived Central American Federation (1821–39) nor Guatemala had ever exercised any authority in the area or even protested the British presence in the 19th century, British Honduras was clearly under British sovereignty. In its constitution of 1945, however, Guatemala stated that British Honduras was the twenty-third department of Guatemala (Guatemala's newest claim on Belize in 1999, however, makes no mention of the 1859 treaty, instead relying on Anglo-Spanish treaties of the 18th century).

In February 1948, Guatemala threatened to invade and forcibly annex the territory, and the British responded by deploying two companies from 2nd Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment. One company deployed to the border and found no signs of any Guatemalan incursion, but the British decided to permanently station a company in Belize City. Since 1954 a succession of military and right-wing governments in Guatemala frequently whipped up nationalist sentiment, generally to divert attention from domestic problems. Guatemala also periodically massed troops on the border with the country in a threatening posture. In 1957, responding to a Guatemalan threat to invade, a company of the Worcesteshire Regiment was deployed, staying briefly and carrying out jungle training before leaving. On 21 January 1958, a force of pro-Guatemalan fighters from the Belize Liberation Army, who had likely been aided and encouraged by Guatemala, crossed the border and raised the Guatemalan flag. A British platoon was then deployed and exchanged fire with them, before arresting some 20 fighters.[1][7]

Negotiations between Britain and Guatemala began again in 1961, but the elected representatives of British Honduras had no voice in these talks. George Price refused an invitation from Guatemalan President Ydígoras Fuentes to make British Honduras an "associated state" of Guatemala. Price reiterated his goal of leading the colony to independence. In 1963, Guatemala broke off talks and ended diplomatic relations with Britain. In 1964, Britain granted British Honduras self-government under a new constitution. The next year, Britain and Guatemala agreed to have an American lawyer, appointed by United States President Lyndon Johnson, mediate the dispute. The lawyer's draft treaty proposed giving Guatemala so much control over British Honduras, including internal security, defence, and external affairs, that the territory would have become more dependent on Guatemala than it was already on Britain. The United States supported the proposals. All parties in British Honduras, however, denounced the proposals, and Price seized the initiative by demanding independence from Britain with appropriate defence guarantees.[1]

A series of meetings, begun in 1969, ended abruptly in 1972 when Britain, in response to intelligence suggesting an imminent Guatemalan invasion,[8] announced it was sending an aircraft carrier and 8,000 troops to Belize to conduct amphibious exercises. Guatemala then massed troops on the border. Talks resumed in 1973, but broke off in 1975 when tensions flared. Guatemala began massing troops on the border, and Britain responded by deploying troops, along with a battery of 105mm field guns, anti-aircraft missile units, six fighter jets, and a frigate. Following this deployment, tensions were defused, largely as a result of many Guatemalan soldiers deserting and returning to their homes.[7]

1975 to independence in 1981

At this point, the Belizean and British governments, frustrated at dealing with the military-dominated regimes in Guatemala, agreed on a new strategy that would take the case for self-determination to various international forums. The Belize government felt that by gaining international support, it could strengthen its position, weaken Guatemala's claims, and make it harder for Britain to make any concessions.[1]

Belize argued that Guatemala frustrated the country's legitimate aspirations to independence and that Guatemala was pushing an irrelevant claim and disguising its own colonial ambitions by trying to present the dispute as an effort to recover territory lost to a colonial power. Between 1975 and 1981, Belizean leaders stated their case for self-determination at a meeting of the heads of Commonwealth of Nations governments in Jamaica, the conference of ministers of the Nonaligned Movement in Peru, and at meetings of the United Nations (UN). The support of the Nonaligned Movement proved crucial and assured success at the UN.[1] Latin American governments initially supported Guatemala. Cuba, however, was the first Latin country, in December 1975, to support Belize in a UN vote that affirmed Belize's right to self-determination, independence, and territorial integrity. The outgoing Mexican president, Luis Echeverría, indicated that Mexico would appeal to the Security Council to prevent Guatemala's designs on Belize from threatening peace in the area. In 1977, Guatemala made further moves against Belize, but was deterred from invading, especially since British fighter jets had by then been permanently stationed there. From 1977 onward, the border was constantly patrolled and observation posts to monitor key points.[7] 1976 Head of government Omar Torrijos of Panama began campaigning for Belize's cause, and in 1979 the Sandinista government in Nicaragua declared unequivocal support for an independent Belize.[1]

In each of the annual votes on this issue in the UN, the United States abstained, thereby giving the Guatemalan government some hope that it would retain United States backing. Finally, in November 1980, with Guatemala completely isolated, the UN passed a resolution that demanded the independence of Belize, with all its territory intact, before the next session of the UN in 1981. The UN called on Britain to continue defending the new nation of Belize. It also called on all member countries to offer their assistance.[1]

A last attempt was made to reach an agreement with Guatemala prior to the independence of Belize. The Belizean representatives to the talks made no concessions, and a proposal, called the Heads of Agreement, was initialled on 11 March 1981. Although the Heads of Agreement would have given only partial control and access to assets in each other's nations, it collapsed when Guatemala renewed its claims to Belize soil and Belizeans rioted against the British and their own government, claiming the Belizean negotiators were making too many concessions to Guatemala. When far-right political forces in Guatemala labelled the proposals as a sell-out, the Guatemalan government refused to ratify the agreement and withdrew from the negotiations. Meanwhile, the opposition in Belize engaged in violent demonstrations against the Heads of Agreement. The demonstrations resulted in four deaths, many injuries, and damage to the property of the People's United Party leaders and their families. A state of emergency was declared. However, the opposition could offer no real alternatives. With the prospect of independence celebrations in the offing, the opposition's morale fell. Independence came to Belize on 21 September 1981, without reaching an agreement with Guatemala.[1]

Post-independence

Britain continued to maintain British Forces Belize to protect the country from Guatemala, consisting of an army battalion and No. 1417 Flight RAF of Harrier fighter jets. The British also trained and strengthened the newly formed Belize Defence Force. There was a serious fear of a Guatemalan invasion in April 1982, when it was thought that Guatemala might take advantage of the Falklands War to invade, but these fears never materialised.

Significant negotiations between Belize and Guatemala, with the United Kingdom as an observer, resumed in 1988. Guatemala recognised Belize's independence in 1991 and diplomatic relations were established.

In 1994, British Forces Belize was disbanded and most British troops left Belize, but the British maintained a training presence via the British Army Training and Support Unit Belize and 25 Flight AAC until 2011, when the last British forces, except for seconded advisers, left Belize.[7][9]

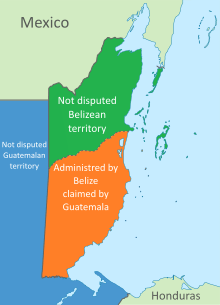

On 19 October 1999, Said Musa, the Prime Minister of Belize, was made aware that Guatemala wanted to renew its claim. As a new line of reasoning for their claim (instead of basing it on the 1859 treaty), Guatemala asserted that it had inherited Spain's 1494 and 18th century claims on Belize and was owed more than half of Belize's land mass, from the Sibun River south.[10] This claim amounts to 12,272 km2 (4,738 sq mi) of territory, or roughly 53% of the country. The claim includes significant portions of the current Belizean Cayo and Belize Districts, as well as all of the Stann Creek and Toledo Districts, well to the north of the internationally accepted border along the Sarstoon River.[11] The majority of Belizeans are strongly opposed to becoming part of Guatemala.

The Guatemalan military placed personnel at the edge of the internationally recognised border. Belizean patrols incorporating Belize Defence Force members and police forces took up positions on their side of the border.[12]

In February 2000, a Belizean patrol shot and killed a Guatemalan in the area of Mountain Pine Ridge Forest Reserve in Belize. On 24 February 2000, personnel from the two nations encountered each other in Toledo District.[12] The two countries held further talks on 14 March 2000, at the Organization of American States (OAS) in the presence of Secretary General César Gaviria at OAS headquarters in Washington, D.C. Eventually they agreed to establish an "adjacency zone" extending one kilometre (0.62 mi) on either side of the 1859 treaty line, now designated the "adjacency line", and to continue negotiations.

Recent developments

In September 2005, Belize, Guatemala and the OAS signed the Confidence Building Measures document, committing the parties to avoid conflicts or incidents on the ground conducive to tension between them. [13]

In June 2008, Belizean Prime Minister Dean Barrow said resolving the dispute was his main political goal. He proposed referenda for the citizens of Belize and Guatemala, asking whether they support referring the issue to the International Court of Justice (ICJ).[14] An agreement on submitting the issue to the ICJ was signed on 8 December 2008, with a referendum to be held on the issue simultaneously in Belize and Guatemala on 6 October 2013, but it was suspended.[15]

In May 2015, Belize allowed Guatemala to proceed with a referendum asking the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to definitively rule on the dispute although Belize by its own admission is not ready for such a vote. A previous treaty between the two countries stipulated that any such vote must be held simultaneously. Guatemala was initially expected to hold its referendum on the issue during its second round of presidential elections in October 2015, but such a vote was not on the ballot.[16] Belize has yet to announce its vote on the matter.[17]

Guatemalan president Jimmy Morales has made statements strongly in support of Guatemala's longstanding territorial claim to Belize, saying, "Something is happening right now, we are about to lose Belize. We have not lost it yet. We still have the possibility of going to the International Court of Justice where we can fight that territory or part of that territory."[16]

The Guatemalan referendum was finally held on 15 April 2018. 95.88% of voters supported sending the claim to the ICJ. Voter turnout was 25%.[18]

See also

- Belize–Guatemala border

- Foreign relations of Belize

- Foreign relations of Guatemala

- Sarstoon Island

- Sapodilla Cayes

- Chiapas (incl. Soconusco), a Mexican state that was claimed by Guatemala until 1895

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Bolland, Nigel. A Country Study: Belize (Tim Merrill, editor). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (January 1992).

- ↑ "Territorial Dispute (Libyun Aruh Jamuhiriyu/Chad)" (PDF), I.C.J. Reports 1994 (Judgment): 37,

Once agreed, the boundary stands, for any other approach would vitiate the fundamental principle of the stability of boundaries, the importance of which has been repeatedly emphasized by the Court (Temple of Preuh Viheur, I.C.J. Reports 1962, p. 34; Aegean Sea Continental Shelf: I.C.J. Reports 1978, p. 36).

- ↑ "Territorial Dispute (Libyun Aruh Jamuhiriyu/Chad)" (PDF), I.C.J. Reports 1994 (Judgment): 37,

A boundary established by treaty thus achieves a permanence which the treaty itself does not necessarily enjoy. The treaty can cease to be in force without in any way affecting the continuance of the boundary.

- ↑ "Frontier Dispute" (PDF), I.C.J. Reports 1986 (Judgment): 568,

By becoming independent, a new State acquires sovereignty with the territorial base and boundaries left to it by the colonial power. This is part of the ordinary operation of the machinery of State succession. International law - and consequently the principle of uti possidetis - applies to the new State (as a State) not with retroactive effect, but immediately and from that moment onwards.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 2009-01-27.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 15 May 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

- 1 2 3 4 British Honduras. Britains-smallwars.com.

- ↑ White, Rowland (1/4/2010). Phoenix squadron. Bantam Press. ISBN 978-0552152907. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Dion E. Phillips: The Military of Belize. Cavehill.uwi.edu.

- ↑ Lauterpacht, Elihu; Stephen Schwebel; Shabtai Rosenne; Francisco Orrego Vicuña (November 2001). "Legal Opinion on Guatemala's Territorial Claim to Belize" (PDF). p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ↑ Contreras, Geovanni; Manuel Hernández (23 January 2013). "Preocupa a Guatemala traba a referendo con Belice". Prensa Libre (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- 1 2 Phillips, Dion E. (2002). "The Military of Belize". University of the West Indies. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ "Clearing of Western Border". Government of Belize Press Office. 25 February 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

Under the Confidence Building Measures of September 2005 signed by Belize, Guatemala and the OAS, the parties are committed to avoid conflicts or incidents on the ground conducive to tension between them.

- ↑ http://www.caribbeannetnews.com/news-8942--6-6--.html

- ↑ "Belize & Guatemala Sign Special Agreement in Washington". Naturalight Productions Ltd. 8 December 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- 1 2 Trujillo, Renee. "Presidential Candidate for Guatemala Says Belize Can Still Be Fought For", LOVE FM, 9 September 2015 (accessed 28 September 2015)

- ↑ Ramos, Adele. "Belize and Guatemala to amend ICJ compromis", Amandala, 12 May 2015. (accessed 14 May 2015)

- ↑ "Guatemalans say "Yes" to the ICJ". The Reporter. 20 April 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- Perez, Arlenie; Chuang Chin-Ta; Farok Afero (2009). "Belize-Guatemala territorial dispute and its implications for conservation" (PDF). Tropical Conservation Science. 2 (1): 11–24.

External links

- Compromis: Belize/Guatemala ICJ Compromis Signed at OAS in Washington, D.C. on 8 December 2008 and Compromis and Videos and U.S. Congratulations and U.K. Congratulations and Photographs and Compromis for Christmas of 8 December 2008 and Belize Leading Counsel of 19 December 2008

- Legal Opinion on Guatemala's Territorial Claim to Belize and MFA Library and GAR and Other Documents and Submission of Belize/Guatemala Case to ICJ in 2009 and Summary of Legal Opinion of 25 November 2008